Australia and the Olympic Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 Olympic Trials Results

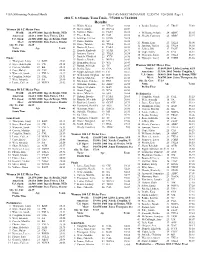

USA Swimming-National Meets Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 12:55 PM 1/26/2005 Page 1 2004 U. S. Olympic Team Trials - 7/7/2004 to 7/14/2004 Results 13 Walsh, Mason 19 VTAC 26.08 8 Benko, Lindsay 27 TROJ 55.69 Women 50 LC Meter Free 15 Silver, Emily 18 NOVA 26.09 World: 24.13W 2000 Inge de Bruijn, NED 16 Vollmer, Dana 16 FAST 26.12 9 Williams, Stefanie 24 ABSC 55.95 American: 24.63A 2000 Dara Torres, USA 17 Price, Keiko 25 CAL 26.16 10 Shealy, Courtney 26 ABSC 55.97 18 Jennings, Emilee 15 KING 26.18 U.S. Open: 24.50O 2000 Inge de Bruijn, NED 19 Radke, Katrina 33 SC 26.22 Meet: 24.90M 2000 Dara Torres, Stanfor 11 Phenix, Erin 23 TXLA 56.00 20 Stone, Tammie 28 TXLA 26.23 Oly. Tr. Cut: 26.39 12 Jamison, Tanica 22 TXLA 56.02 21 Boutwell, Lacey 21 PASA 26.29 Name Age Team 13 Jeffrey, Rhi 17 FAST 56.09 22 Harada, Kimberly 23 STAR 26.33 Finals Time 14 Cope, Haley 25 CAJ 56.11 23 Jamison, Tanica 22 TXLA 26.34 15 Wanezek, Sarah 21 TXLA 56.19 24 Daniels, Elizabeth 22 JCCS 26.36 Finals 16 Nymeyer, Lacey 18 FORD 56.56 25 Boncher, Brooke 21 NOVA 26.42 1 Thompson, Jenny 31 BAD 25.02 26 Hernandez, Sarah 19 WA 26.43 2 Joyce, Kara Lynn 18 CW 25.11 27 Bastak, Ashleigh 22 TC 26.47 Women 100 LC Meter Free 3 Correia, Maritza 22 BA 25.15 28 Denby, Kara 18 CSA 26.50 World: 53.66W 2004 Libby Lenton, AUS 4 Cope, Haley 25 CAJ 25.22 29 Ripple Johnston, Shell 23 ES 26.51 American: 53.99A 2002 Natalie Coughlin, U 5 Wanezek, Sarah 21 TXLA 25.27 29 Medendorp, Meghan 22 IST 26.51 U.S. -

Contents Collection Summary

AIATSIS Collections Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 4116 Cathy Freeman and the Sydney 2000 Olympic games 2000, 2003 and 2010 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY ........................................................................................ 2 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT .................................................................. 2 ACCESS TO COLLECTION ...................................................................................... 3 COLLECTION OVERVIEW ........................................................................................ 3 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE ............................................................................................. 4 SERIES DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................. 6 SERIES 1: NEWSPAPERS 2000 ................................................................................... 6 SERIES 2: MAGAZINES 2000 ...................................................................................... 6 SERIES 3: OLYMPIC TICKETS 2000 ............................................................................. 6 SERIES 4: GUIDES AND BROCHURES 2000 .................................................................. 6 SERIES 5: COMMEMORATIVE STAMPS 2000 ................................................................. 7 SERIES 6: RETIREMENT 2003 .................................................................................... 7 SERIES 7: SYDNEY 2000 -

Dressel, Ledecky Grab Gold As World Records Tumble in Tokyo

14 Sunday, August 1, 2021 Dressel, Ledecky grab gold as world records tumble in Tokyo TOKYO: Caeleb Dressel set a new 100m butterfly of the triumphant 4x100m freestyle team. and outpace Titmus, who clocked a personal best world record to grab his third gold medal in Tokyo He is expected to race the meet-ending men’s 8:13.83 to earn silver ahead of Italy’s Simona yesterday, as Katie Ledecky reinforced her dominance 4x100m medley today. “The freestyle was anybody’s Quadarella. “She (Titmus) made it tough and so it was of distance swimming with a third Olympic 800m race, I knew that going in,” said Dressel. “For the most a lot of fun to race and I just trusted myself, trusted I freestyle title. part, I thought it was going to be between me and could pull it out and swim whatever way I needed to,” Two-time world champion Dressel was always Kristof, so it’s kind of nice when the guy next to you is said Ledecky, who revealed she planned to keep going going to be tough to beat, and he exploded from the the guy you got to beat. It took a world record to potentially up to the 2028 Olympics in Los Angeles. blocks and turned first, roaring home in 49.45 seconds win.” He admitted it was tough tackling three races in a “I’m at least going to ‘24, maybe ‘28 we’ll see,” she to shatter his own previous world best 49.50 set in session. “Good swim or bad swim you’ve got to give said. -

January-February 2003 $ 4.95 Can Alison Sheppard Fastest Sprinter in the World

RUPPRATH AND SHEPPARD WIN WORLD CUP COLWIN ON BREATHING $ 4.95 USA NUMBER 273 www.swimnews.com JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2003 $ 4.95 CAN ALISON SHEPPARD FASTEST SPRINTER IN THE WORLD 400 IM WORLD RECORD FOR BRIAN JOHNS AT CIS MINTENKO BEATS FLY RECORD AT US OPEN ������������������������� ��������������� ���������������������������������� �������������������������������������������� ������������ � �������������������������� � ����������������������� �������������������������� �������������������������� ����������������������� ������������������������� ����������������� �������������������� � ��������������������������� � ���������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������� ��������������������������� �������������������������� ������������ ������� ���������������������������������������������������� ���������������� � ������������������� � ��������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������� ����������������������������� ��������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������������� ������������� �������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������� ������������������� SWIMNEWS / JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2003 3 Contents January-February 2003 N. J. Thierry, Editor & Publisher CONSECUTIVE NUMBER 273 VOLUME 30, NUMBER 1 Marco Chiesa, Business Manager FEATURES Karin Helmstaedt, International Editor Russ Ewald, USA Editor 6 Australian SC Championships Paul Quinlan, Australian Editor Petria Thomas -

2020 Olympic Games Statistics

2020 Olympic Games Statistics - Women’s 400m by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Tokyo: 1) Can Miller-Uibo become only the second (after Perec) 400m sprinter to win the Olympic twice. Summary Page: All time Performance List at the Olympic Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 48.25 Marie -Jose Perec FRA 1 Atlanta 1996 2 2 48.63 Cathy Freeman AUS 2 Atla nta 1996 3 3 48.65 Olga Bryzgina URS 1 Seoul 1988 4 4 48.83 Valerie Brisco -Hooks USA 1 Los Angeles 1984 4 48 .83 Marie Jose -Perec 1 Barcelona 1992 6 5 48.88 Marita Koch GDR 1 Moskva 1980 7 6 49.05 Chandra Cheeseborough USA 2 Los Angeles 1984 Slowest winning time since 1976: 49.62 by Christine Ohuruogu (GBR) in 2008 Margin of Victory Difference Winning time Name Nat Venue Year Max 1.23 49.28 Irena Szewinska POL Montreal 1976 Min 0.07 49.62 Christine Ohuruogu GBR Beijing 20 08 49.44 Shaunae Miller BAH Rio de Janeiro 2016 Fastest time in each round Round Time Name Nat Venue Year Final 48.25 Marie -Jose Perec FRA Atlanta 1996 Semi-final 49.11 Olga Nazarova URS Seoul 1988 First round 50.11 Sanya Richards USA Athinai 2004 Fastest non-qualifier for the final Time Position Name Nat Venue Year 49.91 5sf1 Jillian Richardson CAN Seoul 1988 Best Marks for Places in the Olympics Pos Time Name Nat Venue Year 1 48.25 Marie -Jose Perec FRA Atlanta 1996 2 48.63 Cathy Freeman AUS Atlanta 1996 3 49.10 Falilat Ogunkoya NGR Atlanta 1996 Last nine Olympics: Year Gold Nat Time Silver Nat Time Bronze Nat Time 2016 Shaunae Miller BAH 49.44 Allyson Felix USA 49.51 Shericka Jackson -

The Indigenous Marathon Project Run. Sweat. Inspire Parliamentry Inquiry Into the Contribution of Sport

Submission 049 The Indigenous Marathon Project Run. Sweat. Inspire Parliamentry Inquiry into the contribution of Sport to Indigenous wellbing and mentoring 1 Submission 049 IMP objectives 1. To promote healthy and active lifestyles throughout Indigenous communities nationally and reduce the incidence of Indigenous chronic disease: & 2. To create Indigenous distance running champions and to inspire Indigenous people. Background The Indigenous Marathon Project (IMP) was established in 2009 by World Champion marathon runner and 1983 Australian of the Year, Robert de Castella. IMP annually selects, educates, trains and takes a group of inspirational young Indigenous men and women aged 18-30 to compete in the world’s biggest marathon – the New York City Marathon. IMP is not a sports program. IMP is a social change program that uses the simple act of running as a vehicle to promote the benefits of active and healthy lifestyles and change lives. The group of men and women are similar to rocks in a pond, with their ripple effect continuing to inspire local family and community members as well as thousands of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians nationally. The Project highlights the incredible natural talent that exists within the Australian Indigenous population, with the hope to one day unearth an Indigenous long-distance running champion to take on the African dominance. The core running squad push their physical and mental boundaries to beyond what they ever thought they were capable of, and after crossing the finish line of the world’s biggest marathon, they know they can achieve anything. These runners are trained to become healthy lifestyle leaders by completing a Certificate IV in Health and Leisure, with a focus on Indigenous healthy lifestyle. -

Code De Conduite Pour Le Water Polo

HistoFINA SWIMMING MEDALLISTS AND STATISTICS AT OLYMPIC GAMES Last updated in November, 2016 (After the Rio 2016 Olympic Games) Fédération Internationale de Natation Ch. De Bellevue 24a/24b – 1005 Lausanne – Switzerland TEL: (41-21) 310 47 10 – FAX: (41-21) 312 66 10 – E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.fina.org Copyright FINA, Lausanne 2013 In memory of Jean-Louis Meuret CONTENTS OLYMPIC GAMES Swimming – 1896-2012 Introduction 3 Olympic Games dates, sites, number of victories by National Federations (NF) and on the podiums 4 1896 – 2016 – From Athens to Rio 6 Olympic Gold Medals & Olympic Champions by Country 21 MEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 22 WOMEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 82 FINA Members and Country Codes 136 2 Introduction In the following study you will find the statistics of the swimming events at the Olympic Games held since 1896 (under the umbrella of FINA since 1912) as well as the podiums and number of medals obtained by National Federation. You will also find the standings of the first three places in all events for men and women at the Olympic Games followed by several classifications which are listed either by the number of titles or medals by swimmer or National Federation. It should be noted that these standings only have an historical aim but no sport signification because the comparison between the achievements of swimmers of different generations is always unfair for several reasons: 1. The period of time. The Olympic Games were not organised in 1916, 1940 and 1944 2. The evolution of the programme. -

1/4/2004 Piscina Olímpica Encantada T

Untitled 1/5/04 10:24 AM Licensed to Natacion Fernando Delgado Hy-Tek's Meet Manager II WINTER TRAINING MEET - 1/4/2004 PISCINA OLÍMPICA ENCANTADA TRUJILLO ALTO, PUERTO RICO Results Event 1 Women Open 200 LC Meter Medley Relay =============================================================================== MEET RECORD: * 2:07.03 1/5/2003 SYRACUSE, SYRACUSE- R Wrede, J Jonusaitis, E McDonough, C Jansen School Seed Finals =============================================================================== 1 NOTRE DAME SWIMMING 'A' 2:00.78 2:05.38* 2 NOTRE DAME SWIMMING 'B' 2:05.85 2:06.39* 3 SYRACUSE ORANGEMEN 'A' 2:04.13 2:07.59 4 YALE 'A' 1:59.10 2:09.30 5 ST'S. JOHNS UNIVERSITY 'A' 1:58.35 2:09.94 6 NADADORES SANTURCE 'A' 2:11.51 2:12.48 7 SETON HALL UNIVERSITY 'A' 2:07.98 2:13.43 8 YALE 'B' 2:03.60 2:13.86 9 ST'S. JOHNS UNIVERSITY 'B' 2:01.50 2:14.43 10 GEORGETOWN SWIMMING 'A' 2:10.33 2:15.81 11 ST'S. JOHNS UNIVERSITY 'C' 2:05.00 2:16.53 12 BRANDIES UNIVERSITY 'A' 3:11.00 2:17.50 13 YALE 'C' 2:05.70 2:17.73 14 SETON HALL UNIVERSITY 'B' 2:15.64 2:20.05 15 NADADORES SANTURCE 'B' 2:15.87 2:20.21 16 NOTRE DAME SWIMMING 'C' 2:10.77 2:22.08 17 GEORGETOWN SWIMMING 'B' 2:14.55 2:22.68 18 MONTCLAIR STATE UNIVERSITY 'A' 2:07.30 2:29.65 19 BRANDIES UNIVERSITY 'B' 3:20.00 2:29.75 Event 2 Men Open 200 LC Meter Medley Relay =============================================================================== MEET RECORD: * 1:53.79 1/5/2003 YALE UNIVERSITY, YALE- School Seed Finals =============================================================================== 1 SETON HALL UNIVERSITY 'A' 1:44.09 1:51.80* 2 YALE 'A' 1:44.30 1:53.18* 3 SYRACUSE ORANGEMEN 'A' 1:46.22 1:54.65 4 NADADORES SANTURCE 'A' 1:58.39 1:55.65 5 NADADORES SANTURCE 'B' 2:02.01 1:56.01 6 YALE 'B' 1:49.70 1:56.66 7 ST'S. -

II~Ny Ore, Continue Their Dominance of Their Respective Events

I'_l .N" l'.l('l FI4' There are different opportunities f II A .~1 I' I qi ~ ~ II I i ~ au'aiting all swimmers the year after an Olympic Games. By BtdD ~i,VmHllnoin.~,~i~ tions' exciting new talent to showcase its potential. Neil Walker, FUKUOKA, Japan--The post-Olympic year provides different op- Lenny Krayzelburg, Mai Nakamura, Grant Hackett, Ian Thorpe and portunities for swimmers. others served notice to the swimming world that they will be a force For the successful Atlanta Olympians, the opportunity to contin- to be reckoned with leading up to the 2000 Sydney Olympics. ue their Olympic form still remains, or they can take a back seat The meet was dominated once again by the U.S. and Australian with a hard-earned break from international competition. teams, who between them took home 31 of the 37 gold medals. For those who turned in disappointing results in Atlanta, there Japan (2), Costa Rica (2), China (i) and Puerto Rico (1) all won was the opportunity to atone for their disappointment and return to gold, while charter nation Canada failed to win an event. world-class form. The increasing gap between the top two nations and other com- And for others, the post-Olympic year provides the opportunity peting countries must be a concern for member federations in an era to break into respective national teams and world ranking lists while when most major international competitions are seeing a more even gaining valuable international racing experience. spread of success among nations. The 1997 Pan Pacific Championships Aug. -

The Effortless Swimming Podcast

The Effortless Swimming Podcast Welcome to this episode of Effortless Swimming podcast. Today’s guest is Paul Newsome from Swim Smooth. Paul back in his younger years was an elite Tri-athlete in Britain and he was the British University Triathlon champion, he swum the Rottnest Island Swim and he has also done the English Channel. He is the head coach of Swim Smooth which operates out of Perth. So welcome to the call Paul Not a problem Brenton, nice to be here today. Some of the things that I wanted to cover today were the six different styles of swimming that you teach through Swim Smooth; Some of the differences between the sprinting stroke and a distance stroke? Some of the things that you like to do in training to work on technique; then some of your favourite sets and some of toys that you like to use in the pool? Absolutely, fire away. To get started just give me a bit of background on Swim Smooth, how did you get started and what do you do there? You have a lot of products and you also run training squads there what is the back ground of Swim Smooth? Well my own personal background is swimming; I have been swimming since the age of seven competitively. I got into Triathlons when I was about sixteen years of age and studied sports and exercise science at Bath University in the UK. At that time of was part of the British World Class Performance Triathlon Team which was great to be involved with and I was very fortunate to be coached by some excellent coaches at that time. -

RESULTS 400 Metres Hurdles Women - Final

Doha (QAT) 27 September - 6 October 2019 RESULTS 400 Metres Hurdles Women - Final RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World Record WR 52.16 Dalilah MUHAMMAD USA 29 Doha 4 Oct 2019 Championships Record CR 52.16 Dalilah MUHAMMAD USA 29 Doha 4 Oct 2019 World Leading WL 52.16 Dalilah MUHAMMAD USA 29 Doha 4 Oct 2019 Area Record AR National Record NR Personal Best PB Season Best SB 4 October 2019 21:29 START TIME 26° C 61 % TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY PLACE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH LANE RESULT REACTION Fn 1 Dalilah MUHAMMAD USA 7 Feb 90 6 52.16 WR 0.200 2 Sydney MCLAUGHLIN USA 7 Aug 99 4 52.23 PB 0.161 3 Rushell CLAYTON JAM 18 Oct 92 5 53.74 PB 0.137 4 Lea SPRUNGER SUI 5 Mar 90 9 54.06 NR 0.199 5 Zuzana HEJNOVÁ CZE 19 Dec 86 8 54.23 0.141 6 Ashley SPENCER USA 8 Jun 93 2 54.45 (.444) 0.163 7 Anna RYZHYKOVA UKR 24 Nov 89 3 54.45 (.445) SB 0.173 8 Sage WATSON CAN 20 Jun 94 7 54.82 0.186 ALL-TIME TOP LIST SEASON TOP LIST RESULT NAME VENUE DATE RESULT NAME VENUE 2019 52.16 Dalilah MUHAMMAD (USA) Doha 4 Oct 19 52.16 Dalilah MUHAMMAD (USA) Doha 4 Oct 52.23 Sydney MCLAUGHLIN (USA) Doha 4 Oct 19 52.23 Sydney MCLAUGHLIN (USA) Doha 4 Oct 52.34 Yuliya PECHONKINA (RUS) Tula (Arsenal Stadium) 8 Aug 03 53.11 Ashley SPENCER (USA) Des Moines, IA (USA) 28 Jul 52.42 Melaine WALKER (JAM) Berlin (Olympiastadion) 20 Aug 09 53.73 Shamier LITTLE (USA) Lausanne (Pontaise) 5 Jul 52.47 Lashinda DEMUS (USA) Daegu (DS) 1 Sep 11 53.74 Rushell CLAYTON (JAM) Doha 4 Oct 52.61 Kim BATTEN (USA) Göteborg (Ullevi Stadium) 11 Aug 95 54.06 Lea SPRUNGER (SUI) Doha 4 Oct 52.62 Tonja -

ESCOLA ESTADUAL PROFESSORA ELIZÂNGELA GLÓRIA CARDOSO Formando Jovens Autônomos, Solidários E Competentes

ESCOLA ESTADUAL PROFESSORA ELIZÂNGELA GLÓRIA CARDOSO Formando Jovens Autônomos, Solidários e Competentes ROTEIRO DE ESTUDOS Nº 03 - 2º BIMESTRE/2020 2ª SÉRIE ÁREA DE CONHECIMENTO: COMPONENTE CURRICULAR/DISCIPLINA: Educação Física PROFESSOR: Gilton Cardozo Moreira e Thiago Morbeck TURMA: 23.01 a 23.08 CRONOGRAMA Período de realização das atividades: 06/10/2020 Término das atividades: 21/10/2020 CARGA HORÁRIA DAS ATIVIDADES: 05 COMPETÊNCIA ESPECÍFICA DA ÁREA Compreender o funcionamento das diferentes linguagens e práticas (artísticas, corporais e verbais) e mobilizar esses conhecimentos na recepção e produção de discursos nos diferentes campos de atuação social e nas diversas mídias, para ampliar as formas de participação social, o entendimento e as possibilidades de explicação e interpretação crítica da realidade e para continuar aprendendo. HABILIDADE/OBJETIVO DA ATIVIDADE - (EM13LGG101) Compreender e analisar processos de produção e circulação de discursos, nas diferentes linguagens, para fazer escolhas fundamentadas em função de interesses pessoais e coletivos. ESTUDO ORIENTADO 1- Este Roteiro é material de estudo. Não precisa devolver. Guarde-o para posterior consulta. 2- Devolva somente a Folha de Atividades que está no final do roteiro. 3- Organize na sua agenda semanal um tempo para estudar esse roteiro. 4- Leia atentamente as orientações/dicas do Roteiro de Estudo, dando ênfase nos assuntos que mais tem dificuldades. 5- Faça anotações que julgar pertinentes, a fim de consolidar a aprendizagem e para posterior consulta/estudo. 6- Assista aos vídeos sugeridos quantas vezes forem necessárias, fazendo as anotações que achar importante. 7- Responda todas as atividades propostas. 8- Se tiver alguma dúvida, utilize o grupo de Whatsapp e fale com seu professor.