Appendix One Vegetation of the Caribbean Islands: Descriptions of Alliances and Associations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basseterre Valley National Park Management Plan

Rehabilitation and Management of the Basseterre Valley as a Protection Measure for the Underlying Aquifer Volume 2: National Park Management Plan Prepared for the St. Kitts Water Department by The Ocean Earth Technologies Consortium September 2009 The following is the second volume of the final report compiled by the Ocean Earth Technologies Consortium, prepared for the Water Services Department, Ministry of Public Works, Utilities, Transport & Post Government of St. Kitts & Nevis, for the project entitled: “Rehabilitation and Management of the Basseterre Valley as a Protection Measure for the Underlying Aquifer”. Volume 2 encompasses Output II of the above project, as described in the original contract. Output II is described as the National Park Management Plan for the Basseterre Valley. This report is preceded by an Executive Summary. 201 Alt. 19 Palm Harbor, FL 34683 Website: www.oceanearthtech.com Email: [email protected] Office (727) 787-5975 Fax: (727)786-3577 This volume is the result of a collaborative effort organized by Ocean Earth Technologies Consortium: Volume 2 is Prepared by: Aukerman, Haas and Associates 3403 Green Wing Court, Fort Collins, Colorado 80524. Tel. 970-498-9350 Email: [email protected] Glenn Haas, Ph.D. 201 Alt. 19 Palm Harbor, FL 34683 Website: www.oceanearthtech.com Email: [email protected] Office (727) 787-5975 Fax: (727)786-3577 Rehabilitation and Management of the Basseterre Valley as a Protection Measure for the Underlying Aquifer: Volume 2: A Management Plan for the Proposed National Park in the Basseterre Valley Prepared for the St. Kitts Water Department by The Ocean Earth Technologies Consortium September 2009 Volume II - Executive Summary National Park Management Plan - Key Findings and Solutions Finding #1: The Government of St. -

Kinematic Reconstruction of the Caribbean Region Since the Early Jurassic

Earth-Science Reviews 138 (2014) 102–136 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Kinematic reconstruction of the Caribbean region since the Early Jurassic Lydian M. Boschman a,⁎, Douwe J.J. van Hinsbergen a, Trond H. Torsvik b,c,d, Wim Spakman a,b, James L. Pindell e,f a Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, The Netherlands b Center for Earth Evolution and Dynamics (CEED), University of Oslo, Sem Sælands vei 24, NO-0316 Oslo, Norway c Center for Geodynamics, Geological Survey of Norway (NGU), Leiv Eirikssons vei 39, 7491 Trondheim, Norway d School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, WITS 2050 Johannesburg, South Africa e Tectonic Analysis Ltd., Chestnut House, Duncton, West Sussex, GU28 OLH, England, UK f School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University, Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3YE, UK article info abstract Article history: The Caribbean oceanic crust was formed west of the North and South American continents, probably from Late Received 4 December 2013 Jurassic through Early Cretaceous time. Its subsequent evolution has resulted from a complex tectonic history Accepted 9 August 2014 governed by the interplay of the North American, South American and (Paleo-)Pacific plates. During its entire Available online 23 August 2014 tectonic evolution, the Caribbean plate was largely surrounded by subduction and transform boundaries, and the oceanic crust has been overlain by the Caribbean Large Igneous Province (CLIP) since ~90 Ma. The consequent Keywords: absence of passive margins and measurable marine magnetic anomalies hampers a quantitative integration into GPlates Apparent Polar Wander Path the global circuit of plate motions. -

Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan

Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan Working Plan for Bruxner Park Flora Reserve No 3 Upper North East Forest Agreement Region North East Region Contents Page 1. DETAILS OF THE RESERVE 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Location 2 1.3 Key Attributes of the Reserve 2 1.4 General Description 2 1.5 History 6 1.6 Current Usage 8 2. SYSTEM OF MANAGEMENT 9 2.1 Objectives of Management 9 2.2 Management Strategies 9 2.3 Management Responsibility 11 2.4 Monitoring, Reporting and Review 11 3. LIST OF APPENDICES 11 Appendix 1 Map 1 Locality Appendix 1 Map 2 Cadastral Boundaries, Forest Types and Streams Appendix 1 Map 3 Vegetation Growth Stages Appendix 1 Map 4 Existing Occupation Permits and Recreation Facilities Appendix 2 Flora Species known to occur in the Reserve Appendix 3 Fauna records within the Reserve Y:\Tourism and Partnerships\Recreation Areas\Orara East SF\Bruxner Flora Reserve\FlRWP_Bruxner.docx 1 Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan 1. Details of the Reserve 1.1 Introduction This plan has been prepared as a supplementary plan under the Nature Conservation Strategy of the Upper North East Ecologically Sustainable Forest Management (ESFM) Plan. It is prepared in accordance with the terms of section 25A (5) of the Forestry Act 1916 with the objective to provide for the future management of that part of Orara East State Forest No 536 set aside as Bruxner Park Flora Reserve No 3. The plan was approved by the Minister for Forests on 16.5.2011 and will be reviewed in 2021. -

Memorial Day Sale Exclusive Rates· Book a Balcony Or Above and Receive up to $300 Onboard Credit ^ Plus 50% Reduced Deposit'

Memorial Day Sale Exclusive Rates· Book a Balcony or above and receive Up to $300 Onboard Credit ^ plus 50% Reduced Deposit' Voyage No. Sail Date Itinerary Voyage Description Nights Japan and Alaska Tokyo (tours from Yokohama), Hakodate, Sakaiminato, Busan, Sasebo, Kagoshima, Tokyo (tours from Yokohama), Hakodate, Aomori, Otaru, Cross Q216B 5/8/2022 International DateLine(Cruise-by), Anchorage(Seward), Hubbard Glacier (Cruise-by), Juneau, Glacier Bay National Park (Cruise-by), Ketchikan, Japan and Alaska 38 Victoria, Vancouver, Glacier Bay National Park (Cruise-by), Haines, Hubbard Glacier (Cruise-by), Juneau, Sitka, Ketchikan, Victoria, Vancouver Tokyo (tours from Yokohama), Hakodate, Aomori, Otaru, Cross International Date Line (Cruise-by), Anchorage (Seward), Hubbard Glacier (Cruise- Q217B 5/17/2022 by), Juneau, Glacier Bay National Park (Cruise-by), Ketchikan, Victoria, Vancouver, Glacier Bay National Park (Cruise-by), Haines, Hubbard Glacier Japan and Alaska 29 (Cruise-by), Juneau, Sitka, Ketchikan, Victoria, Vancouver Tokyo (tours from Yokohama), Hakodate, Aomori, Otaru, Cross International Date Line (Cruise-by), Anchorage (Seward), Hubbard Glacier (Cruise- Q217N 5/17/2022 Japan and Alaska 19 by), Juneau, Glacier Bay National Park (Cruise-by), Ketchikan, Victoria, Vancouver Alaska Q218N 6/4/2022 Vancouver, Glacier Bay National Park (Cruise-by), Haines, Hubbard Glacier (Cruise-by), Juneau, Sitka, Ketchikan, Victoria, Vancouver Alaska 10 Q219 6/14/2022 Vancouver, Juneau, Hubbard Glacier (Cruise-by), Skagway, Glacier Bay National Park -

Reporton the Rare Plants of Puerto Rico

REPORTON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO tii:>. CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION ~ Missouri Botanical Garden St. Louis, Missouri July 15, l' 992 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Center for Plant Conservation would like to acknowledge the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the W. Alton Jones Foundation for their generous support of the Center's work in the priority region of Puerto Rico. We would also like to thank all the participants in the task force meetings, without whose information this report would not be possible. Cover: Zanthoxy7um thomasianum is known from several sites in Puerto Rico and the U.S . Virgin Islands. It is a small shrub (2-3 meters) that grows on the banks of cliffs. Threats to this taxon include development, seed consumption by insects, and road erosion. The seeds are difficult to germinate, but Fairchild Tropical Garden in Miami has plants growing as part of the Center for Plant Conservation's .National Collection of Endangered Plants. (Drawing taken from USFWS 1987 Draft Recovery Plan.) REPORT ON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements A. Summary 8. All Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands Species of Conservation Concern Explanation of Attached Lists C. Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [8] species D. Blank Taxon Questionnaire E. Data Sources for Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [B] species F. Pue~to Rico\Virgin Islands Task Force Invitees G. Reviewers of Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [8] Species REPORT ON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO SUMMARY The Center for Plant Conservation (Center) has held two meetings of the Puerto Rlco\Virgin Islands Task Force in Puerto Rico. -

Tribe Cocoeae)

570.5 ILL 59 " 199 0- A Taxonomic mv of the Palm Subtribe Attaleinae (Tribe Cocoeae) SIDiNLV i\ GLASSMAN UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN BIOLOGY 2891 etc 2 8 Digitized by tine Internet Arcinive in 2011 witii funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://www.archive.org/details/taxonomictreatme59glas A Taxonomic Treatment of the Palm Subtribe Attaleinae (Tribe Cocoeae) SIDNEY F. GLASSMAN ILLINOIS BIOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS 59 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS Urbana and Chicago Illinois Biological Monographs Committee David S. Seigler, chair Daniel B. Blake Joseph V. Maddox Lawrence M. Page © 1999 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois Manufactured in the United States of America P 5 4 3 2 1 This edition was digitally printed. © This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Classman, Sidney F. A taxonomic treatment of the palm subtribe Attaleinae (tribe Cocoeae) / Sidney F. Classman. p. cm. — (Illinois biological monographs ; 59) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-252-06786-X (pbk. : acid-free paper) 1. Palms—Classification. 2. Palm.s—Classification —South America. I. Title. II. Series. QK495.P17G548 1999 584'.5—dc21 98-58105 CIP Abstract Detailed taxonomic treatments of all genera in the subtribe AttaleinaesLve included in the present study. Attalea contains 21 species; 2 interspecific hybrids, A. x piassabossu and A. x voeksii; and 1 intergeneric hybrid, x Attabignya minarum. Orbignya has 1 1 species; 1 interspecific hybrid, O. x teixeirana; 2 intergeneric hybrids, x Attabignya minarum and x Maximbignya dahlgreniana; 1 putative intergeneric hybrid, Ynesa colenda; and 1 unde- scribed putative intergeneric hybrid. -

Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae

SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO BOTANY 0 NCTMBER 52 Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae Harold Robinson, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, andJames F. Weedin SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS City of Washington 1981 ABSTRACT Robinson, Harold, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, and James F. Weedin. Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae. Smithsonian Contri- butions to Botany, number 52, 28 pages, 3 tables, 1981.-Chromosome reports are provided for 145 populations, including first reports for 33 species and three genera, Garcilassa, Riencourtia, and Helianthopsis. Chromosome numbers are arranged according to Robinson’s recently broadened concept of the Heliantheae, with citations for 212 of the ca. 265 genera and 32 of the 35 subtribes. Diverse elements, including the Ambrosieae, typical Heliantheae, most Helenieae, the Tegeteae, and genera such as Arnica from the Senecioneae, are seen to share a specialized cytological history involving polyploid ancestry. The authors disagree with one another regarding the point at which such polyploidy occurred and on whether subtribes lacking higher numbers, such as the Galinsoginae, share the polyploid ancestry. Numerous examples of aneuploid decrease, secondary polyploidy, and some secondary aneuploid decreases are cited. The Marshalliinae are considered remote from other subtribes and close to the Inuleae. Evidence from related tribes favors an ultimate base of X = 10 for the Heliantheae and at least the subfamily As teroideae. OFFICIALPUBLICATION DATE is handstamped in a limited number of initial copies and is recorded in the Institution’s annual report, Smithsonian Year. SERIESCOVER DESIGN: Leaf clearing from the katsura tree Cercidiphyllumjaponicum Siebold and Zuccarini. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Chromosome numbers in Compositae, XII. -

Partnerships Between Botanic Gardens and Universities in A

SOUTH FLORIDA-CARIBBEAN CONNECTIONS South Florida-Caribbean Connections education for both Caribbean and US students. An official Memorandum of Understanding Partnerships between Botanic between FIU and the University of the West Indies (UWI) facilitates joint supervision of students by Gardens and Universities in a faculty at the two universities. Two students from UWI at Changing Caribbean World Mona (Tracy Commock and Keron by Javier Francisco-Ortega, Brett Jestrow & M. Patrick Griffith Campbell) are currently enrolled in this program, with major advisor Dr. Phil Rose of UWI and the first two authors as co-major advisor and uman activities the subsequent risk of introducing direct resources to them. Additional committee member, respectively. A have had a major non-native invasive species into partners are the USDA Subtropical project led by Commock concerns impact on the flora their environments. Horticulture Research Station of plant genera only found in Jamaica, and fauna of our Miami, led by Dr. Alan Meerow, for while Campbell’s research focuses on planet. Human- Regarding climate change, molecular genetic projects; and the the conservation status of Jamaican driven climate change and the Caribbean countries are facing two International Center for Tropical endemics. The baseline information immediate challenges. The first generated by these two studies will Hcurrent move to a global economy Botany (ICTB), a collaboration is sea-level rise, which is having between FIU, the National Tropical be critical to our understanding of are among the main factors an immediate impact on seashore Botanic Garden (NTBG) and the how climate change can affect the contributing to the current path habitats. -

By the Becreu^ 01 Uio Luterior NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) 0MB No. 1024-0018 FORT FREDERIK (U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS) Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service____________________________ National Register of Historic Places Registration Form l^NAMEOF PROPERTY Historic Name: FORT FREDERIK (U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS) Other Name/Site Number: FREDERIKSFORT 2. LOCATION Street & Number: S. of jet. of Mahogany Rd. and Rt. 631, N end of Frederiksted Not for publication:N/A City/Town: Frederiksted Vicinity :N/A State: US Virgin Islands County: St. Croix Code: 010 Zip Code:QQ840 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: __ Building(s): X Public-local: __ District: __ Public-State: X Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 2 __ buildings 1 sites 1 __ structures _ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register :_2 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A tfed a by the becreu^ 01 uio luterior NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 FORT FREDERIK (U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS) Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service _______________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Borrichia Frutescens Sea Oxeye1 Edward F

FPS69 Borrichia frutescens Sea Oxeye1 Edward F. Gilman2 Introduction USDA hardiness zones: 10 through 11 (Fig. 2) Planting month for zone 10 and 11: year round The sea oxeye daisy is a true beach plant and may be used Origin: native to Florida in the landscape as a flowering hedge or ground cover (Fig. Uses: mass planting; ground cover; attracts butterflies 1). It spreads by rhizomes and attains a height of 2 to 4 feet. Availability: somewhat available, may have to go out of the The foliage of this plant is fleshy and gray-green in color. region to find the plant The flowering heads of Borrichia frutescens have yellow rays with brownish-yellow disc flowers, and these flowers attract many types of butterflies. Each flower is subtended by a hard, erect, sharp bract. The fruits are small, inconspicuous, four-sided achenes. Figure 2. Shaded area represents potential planting range. Description Height: 2 to 3 feet Figure 1. Sea oxeye. Spread: 2 to 3 feet Plant habit: upright General Information Plant density: moderate Growth rate: slow Scientific name: Borrichia frutescens Texture: medium Pronunciation: bor-RICK-ee-uh froo-TESS-enz Common name(s): sea oxeye Foliage Family: Compositae Plant type: ground cover Leaf arrangement: opposite/subopposite 1. This document is FPS69, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, UF/IFAS Extension. Original publication date October 1999. Reviewed February 2014. Visit the EDIS website at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu. 2. Edward F. Gilman, professor, Environmental Horticulture Department, UF/IFAS Extension, Gainesville, FL 32611. The Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS) is an Equal Opportunity Institution authorized to provide research, educational information and other services only to individuals and institutions that function with non-discrimination with respect to race, creed, color, religion, age, disability, sex, sexual orientation, marital status, national origin, political opinions or affiliations. -

Keel, S. 2005. Caribbean Ecoregional Assessment Cuba Terrestrial

CARIBBEAN ECOREGIONAL ASSESSMENT Cuba Terrestrial Report July 8, 2005 Shirley Keel INTRODUCTION Physical Features Cuba is the largest country in the Caribbean, with a total area of 110,922 km2. The Cuba archipelago consists of the main island (105,007 km2), Isla de Pinos (2,200 km2), and more than one thousand cays (3,715 km2). Cuba’s main island, oriented in a NW-SE direction, has a varied orography. In the NW the major mountain range is the Guaniguanico Massif stretching from west to east with two mountain chains of distinct geological ages and composition—Sierra de los Organos of ancient Jurassic limestone deposited on slaty sandstone, and Sierra del Rosario, younger and highly varied in geological structure. Towards the east lie the low Hills of Habana- Matanzas and the Hills of Bejucal-Madruga-Limonar. In the central part along the east coast are several low hills—from north to south the Mogotes of Caguaguas, Loma Cunagua, the ancient karstic range of Sierra de Cubitas, and the Maniabón Group; while along the west coast rises the Guamuhaya Massif (Sierra de Escambray range) and low lying Sierra de Najasa. In the SE, Sierra Maestra and the Sagua-Baracoa Massif form continuous mountain ranges. The high ranges of Sierra Maestra stretch from west to east with the island’s highest peak, Pico Real (Turquino Group), reaching 1,974 m. The complex mountain system of Sagua-Baracoa consists of several serpentine mountains in the north and plateau-like limestone mountains in the south. Low limestone hills, Sierra de Casas and Sierra de Caballos are situated in the northeastern part of Isla de Pinos (Borhidi, 1991). -

Brya Ebenus (L.) DC

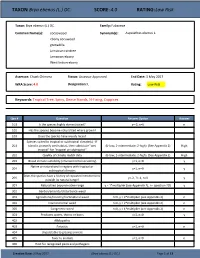

TAXON: Brya ebenus (L.) DC. SCORE: 4.0 RATING: Low Risk Taxon: Brya ebenus (L.) DC. Family: Fabaceae Common Name(s): cocoswood Synonym(s): Aspalathus ebenus L. ebony cocuwood grenadilla Jamaican raintree Jamaican-ebony West Indian-ebony Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 3 May 2017 WRA Score: 4.0 Designation: L Rating: Low Risk Keywords: Tropical Tree, Spiny, Dense Stands, N-Fixing, Coppices Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 y 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens Creation Date: 3 May 2017 (Brya ebenus (L.) DC.) Page 1 of 13 TAXON: Brya ebenus (L.) DC.