20-366 TSAC Rep Brooks Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Business and Conservative Groups Helped Bolster the Sedition Caucus’ Coffers During the Second Fundraising Quarter of 2021

Big Business And Conservative Groups Helped Bolster The Sedition Caucus’ Coffers During The Second Fundraising Quarter Of 2021 Executive Summary During the 2nd Quarter Of 2021, 25 major PACs tied to corporations, right wing Members of Congress and industry trade associations gave over $1.5 million to members of the Congressional Sedition Caucus, the 147 lawmakers who voted to object to certifying the 2020 presidential election. This includes: • $140,000 Given By The American Crystal Sugar Company PAC To Members Of The Caucus. • $120,000 Given By Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s Majority Committee PAC To Members Of The Caucus • $41,000 Given By The Space Exploration Technologies Corp. PAC – the PAC affiliated with Elon Musk’s SpaceX company. Also among the top PACs are Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, and the National Association of Realtors. Duke Energy and Boeing are also on this list despite these entity’s public declarations in January aimed at their customers and shareholders that were pausing all donations for a period of time, including those to members that voted against certifying the election. The leaders, companies and trade groups associated with these PACs should have to answer for their support of lawmakers whose votes that fueled the violence and sedition we saw on January 6. The Sedition Caucus Includes The 147 Lawmakers Who Voted To Object To Certifying The 2020 Presidential Election, Including 8 Senators And 139 Representatives. [The New York Times, 01/07/21] July 2021: Top 25 PACs That Contributed To The Sedition Caucus Gave Them Over $1.5 Million The Top 25 PACs That Contributed To Members Of The Sedition Caucus Gave Them Over $1.5 Million During The Second Quarter Of 2021. -

Employees of Northrop Grumman Political Action Committee (ENGPAC) 2017 Contributions

Employees of Northrop Grumman Political Action Committee (ENGPAC) 2017 Contributions Name Candidate Office Total ALABAMA $69,000 American Security PAC Rep. Michael Dennis Rogers (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 Byrne for Congress Rep. Bradley Roberts Byrne (R) Congressional District 01 $5,000 BYRNE PAC Rep. Bradley Roberts Byrne (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 Defend America PAC Sen. Richard Craig Shelby (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 Martha Roby for Congress Rep. Martha Roby (R) Congressional District 02 $10,000 Mike Rogers for Congress Rep. Michael Dennis Rogers (R) Congressional District 03 $6,500 MoBrooksForCongress.Com Rep. Morris Jackson Brooks, Jr. (R) Congressional District 05 $5,000 Reaching for a Brighter America PAC Rep. Robert Brown Aderholt (R) Leadership PAC $2,500 Robert Aderholt for Congress Rep. Robert Brown Aderholt (R) Congressional District 04 $7,500 Strange for Senate Sen. Luther Strange (R) United States Senate $15,000 Terri Sewell for Congress Rep. Terri Andrea Sewell (D) Congressional District 07 $2,500 ALASKA $14,000 Sullivan For US Senate Sen. Daniel Scott Sullivan (R) United States Senate $5,000 Denali Leadership PAC Sen. Lisa Ann Murkowski (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 True North PAC Sen. Daniel Scott Sullivan (R) Leadership PAC $4,000 ARIZONA $29,000 Committee To Re-Elect Trent Franks To Congress Rep. Trent Franks (R) Congressional District 08 $4,500 Country First Political Action Committee Inc. Sen. John Sidney McCain, III (R) Leadership PAC $3,500 (COUNTRY FIRST PAC) Gallego for Arizona Rep. Ruben M. Gallego (D) Congressional District 07 $5,000 McSally for Congress Rep. Martha Elizabeth McSally (R) Congressional District 02 $10,000 Sinema for Arizona Rep. -

Capitol Insurrection at Center of Conservative Movement

Capitol Insurrection At Center Of Conservative Movement: At Least 43 Governors, Senators And Members Of Congress Have Ties To Groups That Planned January 6th Rally And Riots. SUMMARY: On January 6, 2021, a rally in support of overturning the results of the 2020 presidential election “turned deadly” when thousands of people stormed the U.S. Capitol at Donald Trump’s urging. Even Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell, who rarely broke with Trump, has explicitly said, “the mob was fed lies. They were provoked by the President and other powerful people.” These “other powerful people” include a vast array of conservative officials and Trump allies who perpetuated false claims of fraud in the 2020 election after enjoying critical support from the groups that fueled the Capitol riot. In fact, at least 43 current Governors or elected federal office holders have direct ties to the groups that helped plan the January 6th rally, along with at least 15 members of Donald Trump’s former administration. The links that these Trump-allied officials have to these groups are: Turning Point Action, an arm of right-wing Turning Point USA, claimed to send “80+ buses full of patriots” to the rally that led to the Capitol riot, claiming the event would be one of the most “consequential” in U.S. history. • The group spent over $1.5 million supporting Trump and his Georgia senate allies who claimed the election was fraudulent and supported efforts to overturn it. • The organization hosted Trump at an event where he claimed Democrats were trying to “rig the election,” which he said would be “the most corrupt election in the history of our country.” • At a Turning Point USA event, Rep. -

2017 Official General Election Results

STATE OF ALABAMA Canvass of Results for the Special General Election held on December 12, 2017 Pursuant to Chapter 12 of Title 17 of the Code of Alabama, 1975, we, the undersigned, hereby certify that the results of the Special General Election for the office of United States Senator and for proposed constitutional amendments held in Alabama on Tuesday, December 12, 2017, were opened and counted by us and that the results so tabulated are recorded on the following pages with an appendix, organized by county, recording the write-in votes cast as certified by each applicable county for the office of United States Senator. In Testimony Whereby, I have hereunto set my hand and affixed the Great and Principal Seal of the State of Alabama at the State Capitol, in the City of Montgomery, on this the 28th day of December,· the year 2017. Steve Marshall Attorney General John Merrill °\ Secretary of State Special General Election Results December 12, 2017 U.S. Senate Geneva Amendment Lamar, Amendment #1 Lamar, Amendment #2 (Act 2017-313) (Act 2017-334) (Act 2017-339) Doug Jones (D) Roy Moore (R) Write-In Yes No Yes No Yes No Total 673,896 651,972 22,852 3,290 3,146 2,116 1,052 843 2,388 Autauga 5,615 8,762 253 Baldwin 22,261 38,566 1,703 Barbour 3,716 2,702 41 Bibb 1,567 3,599 66 Blount 2,408 11,631 180 Bullock 2,715 656 7 Butler 2,915 2,758 41 Calhoun 12,331 15,238 429 Chambers 4,257 3,312 67 Cherokee 1,529 4,006 109 Chilton 2,306 7,563 132 Choctaw 2,277 1,949 17 Clarke 4,363 3,995 43 Clay 990 2,589 19 Cleburne 600 2,468 30 Coffee 3,730 8,063 -

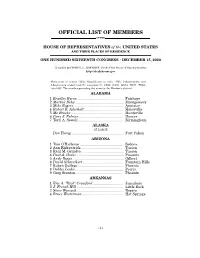

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................ -

HR 4438 Don't Tax Higher Education

17 Elk Street 518-436-4781 www.cicu.org Albany, NY 12207 518-436-0417 fax www.nycolleges.org [email protected] Office of the President October 11, 2019 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Kevin McCarthy Speaker Minority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives The Honorable Bobby Scott The Honorable Virginia Foxx Chairman Ranking Member Committee on Education and Labor Committee on Education and Labor U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives The Honorable Brendan Boyle The Honorable Bradley Byrne Pennsylvania’s 2nd District Alabama’s 1st District U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives Dear Speaker Pelosi, Minority Leader McCarthy, Chairman Scott and Ranking Member Foxx, Congressman Boyle, and Congressman Byrne: On behalf of the 100+ private, not-for-profit colleges in New York State, I write to you today in support of the H.R. 4438 Don’t Tax Higher Education Act, sponsored by Representatives Boyle and Byrne. This legislation would repeal the excise tax on investment income of private colleges and universities. Under current law, certain private colleges and universities are subject to a 1.4 percent excise tax on net investment income. This provision applies to private colleges and universities that have endowment assets of $500,000 per Full Time Equivalent (FTE) student. State colleges and universities are not subject to this provision even though many enjoy very strong endowments. H.R. 4438 would correct the ill-conceived decision to tax higher education that was made in 2017. Endowments are used prudently to support the higher education mission of an institution, and a tax on them invariably lessens what can be spent on students and on providing access to a high-quality education. -

MCF CONTRIBUTIONS JULY 1 - DECEMBER 31, 2016 Name State Candidate Amount U.S

MCF CONTRIBUTIONS JULY 1 - DECEMBER 31, 2016 Name State Candidate Amount U.S. House Robert Aderholt for Congress AL Rep. Robert Aderholt $2,000 ALABAMA TOTAL U.S. House Crawford for Congress AR Rep. Rick Crawford $1,500 Womack for Cogress Committee AR Rep. Stephen Womack $500 ARKANSAS TOTAL U.S. House Kyrsten Sinema for Congress AZ Rep. Kyrtsen Sinema $500 ARIZONA TOTAL U.S. House Denham for Congress CA Rep. Jeff Denham $1,500 Garamendi for Congress CA Rep. John Garamendi $500 Kevin McCarthy for Congress CA Rep. Kevin McCarthy $1,000 Valadao for Congress CA Rep. David Valadao $1,500 U.S. House Leadership Majority Committee PAC--Mc PAC CA Rep. Kevin McCarthy $5,000 State Assembly Adam Gray for Assembly 2016 CA Assm. Adam Gray $1,500 Catharine Baker for Assembly 2016 CA Assm. Catharine Baker $2,500 Cecilia Aguiar-Curry for Assembly 2016 CA Assm. Cecilia Aguiar-Curry $2,000 Chad Mayes for Assembly 2016 CA Assm. Chad Mayes $2,000 James Gallagher for Assembly 2016 CA Assm. James Gallagher $1,500 Patterson for Assembly 2016 CA Assm. James Patterson $2,000 Jay Obernolte for Assembly 2016 CA Assm. Jay Obernolte $1,500 Jim Cooper for Assembly 2016 CA Assm. Jim Cooper $1,500 Jimmy Gomez for Assembly 2016 CA Assm. Jimmy Gomez $1,500 Dr. Joaquin Arambola for Assembly 2016 CA Assm. Joaquin Arambula $1,500 Ken Cooley for Assembly 2016 CA Assm. Ken Cooley $1,500 Miguel Santiago for Assembly 2016 CA Assm. Miguel Santiago $1,500 Rudy Salas for Assembly 2016 CA Assm. -

Congressional Directory ALABAMA

2 Congressional Directory ALABAMA ALABAMA (Population 2010, 4,779,736) SENATORS RICHARD C. SHELBY, Republican, of Tuscaloosa, AL; born in Birmingham, AL, May 6, 1934; education: attended the public schools; B.A., University of Alabama, 1957; LL.B., University of Alabama School of Law, 1963; professional: attorney; admitted to the Alabama bar in 1961 and commenced practice in Tuscaloosa; member, Alabama State Senate, 1970–78; law clerk, Supreme Court of Alabama, 1961–62; city prosecutor, Tuscaloosa, 1963–71; U.S. Magistrate, Northern District of Alabama, 1966–70; special assistant Attorney General, State of Alabama, 1969–71; chairman, legislative council of the Alabama Legislature, 1977–78; former president, Tuscaloosa County Mental Health Association; member of Alabama Code Revision Committee, 1971–75; member: Phi Alpha Delta legal fraternity, Tuscaloosa County; Alabama and American bar associations; First Presbyterian Church of Tuscaloosa; Exchange Club; American Judicature Society; Alabama Law Institute; married: the former Annette Nevin in 1960; children: Richard C., Jr., and Claude Nevin; committees: chair, Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs; Appropriations; Rules and Administration; elected to the 96th Congress on No- vember 7, 1978; reelected to the three succeeding Congresses; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 4, 1986; reelected to each succeeding Senate term. Office Listings http://shelby.senate.gov twitter: @senshelby 304 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 .................................................. (202) 224–5744 Chief of Staff.—Alan Hanson. FAX: 224–3416 Personal Secretary / Appointments.—Anne Caldwell. Communications Director.—Torrie Miller. The Federal Building, 1118 Greensboro Avenue, #240, Tuscaloosa, AL 35401 ..................... (205) 759–5047 Vance Federal Building, Room 321, 1800 5th Avenue North, Birmingham, AL 35203 ....... -

In the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Case: 14-20039 Document: 00512632249 Page: 1 Date Filed: 05/15/2014 No. 14-20039 In the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit STEVEN F. HOTZE, M.D., AND BRAIDWOOD MANAGEMENT, INC., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. KATHLEEN SEBELIUS, U.S. SECRETARY OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES, AND JACOB J. LEW, U.S. SECRETARY OF THE TREASURY, IN THEIR OFFICIAL CAPACITIES, Defendants-Appellees. ON APPEAL FROM U.S. DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS, HOUSTON DIVISION, CIVIL NO. 4:13-CV-01318, HON. NANCY F. ATLAS AMICI CURIAE BRIEF OF SENATORS JOHN CORNYN AND TED CRUZ, CONGRESSMAN PETE SESSIONS, ET AL. (ADDITIONAL AMICI CURIAE ON INSIDE COVER) IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS AND REVERSAL Lawrence J. Joseph, D.C. Bar #464777 1250 Connecticut Ave, NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036 Tel: 202-355-9452 Fax: 202-318-2254 Email: [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae Case: 14-20039 Document: 00512632249 Page: 2 Date Filed: 05/15/2014 No. 14-20039 In the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ADDITIONAL AMICI CURIAE: U.S. REPS. ROBERT ADERHOLT, JOE BARTON, KERRY BENTIVOLIO, CHARLES W. BOUSTANY, JR., KEVIN BRADY, PAUL BROUN, VERN BUCHANAN, JOHN CARTER, STEVE CHABOT, TOM COLE, K. MICHAEL CONAWAY, PAUL COOK, KEVIN CRAMER, JOHN CULBERSON, JEFF DUNCAN, BLAKE FARENTHOLD, JOHN FLEMING, BILL FLORES, SCOTT GARRETT, BOB GIBBS, LOUIE GOHMERT, TREY GOWDY, MORGAN GRIFFITH, RALPH M HALL, RICHARD HUDSON, TIM HUELSKAMP, LYNN JENKINS, BILL JOHNSON, SAM JOHNSON, WALTER JONES, STEVE KING, JACK KINGSTON, JOHN KLINE, DOUG LAMALFA, LEONARD LANCE, JAMES LANKFORD, MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, PATRICK T. -

2018 July Newsletter

1 Visit our website at ALGOP.org Dear Alabama Republican, Thank you for your support of the Alabama Republican Party and all our candidates during this primary election season. We are proud of every ALGOP candidate who sacrificed their valuable time to run for public office. Are you ready to help us keep Alabama Red? With the primary elections behind us, the ALGOP is united and ready to move forward as one team to defeat the democrats on November 6th. We would love to have you help us volunteer to ensure a victory this fall. Sign up to volunteer with the ALGOP here. It’s great to be a Republican, Terry Lathan Chairman, Alabama Republican Party 2 In Memory of… Bridgett Marshall ALGOP Statement on President Trump Wife of Alabama Attorney General Nominating Judge Brett Kavanaugh to Steve Marshall the United States Supreme Court George Noblin Montgomery, AL READ MORE HERE ALGOP State Executive Alabama Republican Party Chairman Committee Member Terry Lathan Comments on the Betty Callahan Alabama Republican Primary Runoff Mobile, AL Election Results Wife of former AL State Senator George Callahan READ MORE HERE Lee James Mobile,AL Republicans upbeat about November Republican elections despite Trump-Putin uproar activist READ MORE HERE At RNC meeting, no one is sweating Trump-Putin summit READ MORE HERE Blue Hope, Tough Math: Alabama Democrats Eye November READ MORE HERE CONNECT WITH US ON SOCIAL MEDIA Alabama Republican Party Alabama Republican Party Chairman Terry Lathan @ALGOP Registration Deadline: @ChairmanLathan Thursday, August 2nd @alabamagop @chairmanlathan Cullman location: click here. Montgomery location: click here. -

List of Government Officials (May 2020)

Updated 12/07/2020 GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS PRESIDENT President Donald John Trump VICE PRESIDENT Vice President Michael Richard Pence HEADS OF EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTS Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar II Attorney General William Barr Secretary of Interior David Bernhardt Secretary of Energy Danny Ray Brouillette Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Benjamin Carson Sr. Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao Secretary of Education Elisabeth DeVos (Acting) Secretary of Defense Christopher D. Miller Secretary of Treasury Steven Mnuchin Secretary of Agriculture George “Sonny” Perdue III Secretary of State Michael Pompeo Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross Jr. Secretary of Labor Eugene Scalia Secretary of Veterans Affairs Robert Wilkie Jr. (Acting) Secretary of Homeland Security Chad Wolf MEMBERS OF CONGRESS Ralph Abraham Jr. Alma Adams Robert Aderholt Peter Aguilar Andrew Lamar Alexander Jr. Richard “Rick” Allen Colin Allred Justin Amash Mark Amodei Kelly Armstrong Jodey Arrington Cynthia “Cindy” Axne Brian Babin Donald Bacon James “Jim” Baird William Troy Balderson Tammy Baldwin James “Jim” Edward Banks Garland Hale “Andy” Barr Nanette Barragán John Barrasso III Karen Bass Joyce Beatty Michael Bennet Amerish Babulal “Ami” Bera John Warren “Jack” Bergman Donald Sternoff Beyer Jr. Andrew Steven “Andy” Biggs Gus M. Bilirakis James Daniel Bishop Robert Bishop Sanford Bishop Jr. Marsha Blackburn Earl Blumenauer Richard Blumenthal Roy Blunt Lisa Blunt Rochester Suzanne Bonamici Cory Booker John Boozman Michael Bost Brendan Boyle Kevin Brady Michael K. Braun Anthony Brindisi Morris Jackson “Mo” Brooks Jr. Susan Brooks Anthony G. Brown Sherrod Brown Julia Brownley Vernon G. Buchanan Kenneth Buck Larry Bucshon Theodore “Ted” Budd Timothy Burchett Michael C. -

2020 Election Recap

2020 Election Recap Below NACCHO summarizes election results and changes expected for 2021. Democrats will continue to lead the House of Representatives…but with a smaller majority. This means that many of the key committees for public health will continue to be chaired by the same members, with notable exceptions of the Appropriations Committee, where Chair Nita Lowey (D-NY) did not run for reelection; the Agriculture Committee, which has some jurisdiction around food safety and nutrition, whose Chair, Colin Peterson (D-MN) lost, as well as the Ranking Member for the Energy and Commerce Committee, Rep. Greg Walden, (R-OR) who did not run for reelection. After the 117th Congress convenes in January, internal leadership elections will determine who heads these and other committees. The following new Representatives and Senators are confirmed as of January 7. House of Representatives Note: All House of Representative seats were up for re-election. We list only those where a new member will be coming to Congress below. AL-1: Republican Jerry Carl beat Democrat James Averhart (open seat) Carl has served a member of the Mobile County Commission since 2012. He lists veterans’ health care and border security as policy priorities. Rep. Bradley Byrne (R-AL) vacated the seat to run for Senate. AL-2: Republican Barry Moore beat Democrat Phyllis Harvey-Hall (open seat) Moore served in the Alabama House of Representatives from 2010 to 2018. The seat was vacated by Rep. Martha Roby (R-AL) who retired. CA-8 Republican Jay Obernolte beat Democrat Christine Bubser (open seat) Jay Obsernolte served in the California State Assembly since 2014.