The Pupils‟ Views

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activities and Events

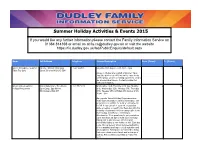

Summer Holiday Activities & Events 2015 If you would like any further information please contact the Family Information Service on 01384 814398 or email us at [email protected] or visit the website https://fis.dudley.gov.uk/fsd/PublicEnquiry/default.aspx Name Full Address Telephone Service Description From (Years) To (Years) Access In Dudley - Summer Brierley Hill Civic Hall, Bank 01384 569505 6DWXUGD\WK$XJXVWSPSP 0 99 Table Top Sale Street, Brierley Hill, DY5 3DH $FFHVVLQ'XGOH\DUHKRVWLQJD6XPPHU7DEOH 7RS6DOHDW%ULHUOH\+LOO&LYLF+DOOWRUDLVHIXQGV IRUWKHJURXSDVZHOODVUDLVLQJDZDUHQHVVRIZKR ZHDUHDQGZKDWZHGR&RQWDFWSURYLGHUIRU IXUWKHULQIRUPDWLRQ Ackers School Summer Ackers Adventure, The Ackers 0121 772 5111 :HGQHVGD\QG7KXUVGD\WK-XO\0RQGD\ 8 16 Holiday Programme Base Camp, Sparkbrook, WK:HGQHVGD\WK0RQGD\WK7KXUVGD\ Birmingham, B11 2PY WK7XHVGD\WK )ULGD\WK$XJXVW DPSP 2XUSRSXODU6FKRRO+ROLGD\3URJUDPPHUXQV HYHU\VFKRROKROLGD\RQYDULRXVZHHNGD\V7KH SURJUDPPHLVVXLWDEOHIRU\UROGVZKRFDQ EHOHIWLQRXUFDUHDIWHUDSDUHQWRUJXDUGLDQ VLJQVDPHGLFDOFRQVHQWIRUP(DFKGD\ZLOORIIHU DYDULHW\RIDFWLYLWLHVIRUWKH\RXQJSHRSOHWRWU\ IURP6NLLQJWR$UFKHU\WR&OLPELQJWR 2ULHQWHHULQJ,W¶VDJUHDWZD\WRJHW\RXQJVWHUV RXWLQWKHIUHVKDLUGXULQJWKHLUVFKRROKROLGD\ WDNLQJSDUWLQDGYHQWXURXVDFWLYLWLHVDQG SRWHQWLDOO\ILQGLQJDQHZKREE\RUVNLOO(DFKGD\ FRVWV SHUSHUVRQZKLFKLQFOXGHVLQVWUXFWLRQ IURPDTXDOLILHGDQGH[SHULHQFHGLQVWUXFWRUDQG DOOHTXLSPHQW3DUWLFLSDQWVDUHDGYLVHGWREULQJ WKHLURZQUHIUHVKPHQWVOXQFKDQGDFKDQJHRI FORWKHV3UHERRNLQJLVHVVHQWLDORQ Name Full Address Telephone Service Description From (Years) To (Years) -

ACF Virtual Events Brochure

Virtual Events & Experiences ‘PROVIDING FUN AND MEMORABLE EXPERIENCES THAT UNIFY PEOPLE’ BESPOKE ACF Teambuilding and Events is one of the UK’s leading team building and event companies with over 20 years of experience running thousands of fantastic corporate events. No two events are the same, we tailor make each package to suit you and your event. VIRTUAL EVENTS Here at ACF Teambuilding & Events, we’ve called upon our wealth of industry experience and creative expertise to launch virtual team building events for remote teams to enjoy! We understand just how important it is to boost team morale and encourage staff engagement as we navigate the new normal, which is why we’ve made each of our online team building events as interactive and fun as possible. Our events are organised by our experienced instructors so, for the most BRINGpart, TEAMS all TOGETHERyou need to do is rally the team together and show up! Which one will you choose? CONTENTS Page 5 – 13. Food and Drink Page 14 – 19. Song and Dance Page 20 – 23. Team Challenges Page 24 – 27. Chill Page 28 – 31. Entertainment Page 32 – 36. Gameshows Page 37 - 38. Virtual Events Testimonials Page 39. Contact Us BRINGING TEAMS TOGETHER FOOD AND DRINK CREATE AND TASTE Each of these team building activities provides the opportunity to learn a new skill within a relaxed, fun environment. ✓ Bake Along ✓ The Culinary Games ✓ Chocolate Making ✓ Chocolate Challenge ✓ Cooking Workshop ✓ Cocktail Making ✓ Wine Tasting BAKE ALONG Competitive or Collaborative Duration: 2 Hours Number of Clients: 3 – 50 guests Our virtual bake-along will make soggy- bottomed sponges a thing of the past as you’ll be baking your sweet treats whilst guided by a leading Michelin Star chef. -

May 2015•Issue31 How Would You Spend £100,000? Building Abetter Repairs Service

May 2015 • Issue 31 A newsletter by residents for residents May Day Alert! Phoenix Festival returns Page 3 Building a better repairs service. How you can help Page 6 community news How would you spend £100,000? Use your vote Page 11 Welcome… Welcome to Community News Thank you for picking up the May issue of Community News. We hope you enjoy your read. WIN! ‘Spot yourself!’ If this is you, pictured at our Spring We love to receive feedback from other residents about Community News. Community Links Gathering in It’s your newsletter! At the Phoenix Festival in May we’ll be asking what you March, please contact us to claim think about Community News and your suggestions for improving it. We’ll your £25 shopping voucher. also be scouting for cover stars for our August issue, so make sure to visit our stall and have your picture taken! If you have other ideas on how we can improve communications to residents, we’d love to hear from you. If you can’t make meetings, then we welcome your feedback online. Enjoy this issue, and we’ll see you on 9 May at the Phoenix Festival! Best wishes, from the Residents Communications Group How to keep in touch By phone: from 8am-5pm, Monday to Friday (and for emergency calls at all other times) 0800 0285 700 Email: [email protected] Web: www.phoenixch.org.uk • www.thegreenman.com Twitter: @phoenixtogether @greenmanhub for all the latest news and opportunities Easter bonnets at our Spring Community Youtube: www.youtube.com/phoenixtogether Links Gathering Visit: by appointment from 9am to 5pm, Monday to Friday Contents at The Green Man, 355 Bromley Road, SE6 2RP Staff training: emergency phone service only, 3 May Day Alert! 2-3pm every other Tuesday Phoenix Festival 2015 4+5 Round the houses Please note, The Green Man 6 Focus on.. -

Crimes Committed by Terrorist Groups: Theory, Research and Prevention

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Crimes Committed by Terrorist Groups: Theory, Research and Prevention Author(s): Mark S. Hamm Document No.: 211203 Date Received: September 2005 Award Number: 2003-DT-CX-0002 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Crimes Committed by Terrorist Groups: Theory, Research, and Prevention Award #2003 DT CX 0002 Mark S. Hamm Criminology Department Indiana State University Terre Haute, IN 47809 Final Final Report Submitted: June 1, 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 2003-DT-CX-0002 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .............................................................. iv Executive Summary.................................................... -

RATE CARD INDIVIDUAL RATES Rs. DECOR PACKAGES Rs

CRAZYBIRTHDAYS- RATE CARD INDIVIDUAL RATES Rs. DECOR PACKAGES Rs. 100 Hydrogen Gas Balloon Décor 2800 SIMPLE THEME DECOR 6500 100 Helium Gas Balloon Decor 5500 8 x 6 theme backdrop 50 Polka Dot hydrogen gas balloon Décor 3500 5 theme cut-outs 300 Balloon decor + Thermocol Happy Birthday Banner 2600 300 balloon decor Two 3 feet Balloon pillar Balloon bunches of 3 or 5 around ARTISTS-3HRS SERVICE Balloon Modelling 2500 PLAIN THEME DECOR Tattoo Artists 2500 10X7 Theme backdrop 8500 Face Painting 2500 8 Theme cut-outs Nail Artistry 2500 Theme based name board Pottery Theme based welcome 4200 board 500 balloon decor of 2 Clay Modelling (Clay Art) 4200 color includes- Hair Braiding 2500 Two 6 feet Balloon pillar Balloon bunches of 3 or 5 Kids Corner 9000 around Caricature (Pencil Face Art) 3800 25 polka dot Balloons Caricature on mug (120 per mug- White regular size mug) 120 Mehandi 2500 2D THEME DECOR 15000 STAGE ARTISTS 10x7 Theme backdrop Magician (45mins service) 4000 Theme side panels- 2x7 Table Magician (45mins service) 4500 12 Theme cut-outs B+ Game Host for a Party (1hr 30min Customized Theme based service) 4000 name board A+ Game Host for a Party (1hr 3 Customized Theme based 0min service) 5500 welcome board Puppet Show- Katputli Dance (30 5 Theme props- Based on mins service) 6000 theme Cakes | Foods | Party Supplies | Gifts | Return Gifts | Disney Theme Parties | Entertainment. One Stop Shop for ALL your party needs. Visit us @ www.crazybirthdays.in Puppet Show- Hand puppet (30 mins 1000 balloon decor of 4 service) 6500 color includes- -

Sculpture Instructions, Alphabetical Listing

Sculptures in the mail featured sponsor: Sculpture Instructions, alphabetical listing (with links to the original messages) Stars ( ) next to entries indicate that they contain graphical instructions. Title - (Author, Subject, Date, Time) ● Acrobats - (Simon James) ● Acrobats - (David G) ● Airplane - (Larry Moss) ● Alien - (Mark Burginger) ● Alligator - (Bruce Kalver) ● Alligator - (Kevin Young) ● Angel - (Donna Jaffke) ● Angel - (Troy Perry) ● Angel - (Tootsie the Clown) ● Ape -(Alan Simkins) http://www.balloonhq.com/faq/SculptureNames.html (1 of 17) [11/28/1999 1:27:58 PM] Sculptures in the mail ● Antler Hat - (Chris Lawton) ● Apples - (Bruce Kalver) ● Ariel (Little Mermaid) - (Lorna Paris) ● Arm Animal -(Dave Jarvis) ● Baboon -(Jim Batten) ● Ball in Balloon Toy - (Carol Warren) ● Ball in Balloon Toy - Missile Balloon -(Chris Maxwell) ● Ball-in-balloon toys - (Edward Cardinal) ● Balloon Juggling Balls - (Larry Hirsch) ● Balloon Trick - Norm Carpenter ● Balloon Tricks - Troy Perry ● Bananas - (Bruce Kalver) ● Banjo -(Larry Moss) ● Barney routine - (Michele Rothstein) ● Base - (Arla Albers) ● Base - (Troy Perry) ● Base for flower bouquet - (Arlene Powers) ● Baseball Hat - (Steven Hayden Brown) ● Baseball Player - (Mark Balzer) ● Basket - (Bruce Kalver) ● Basketball - (Popsicle the Clown) ● Basketball - (Fred Harshberger) ● Basketball - (Magic Mike) ● Basketball - (Mark Balzer) ● Basketball - (Mark Balzer) ● Basketball hoop - (Fred Harshberger) ● Basketball Player Hat - (Adrienne Vincent) ● Bass -(Sir Twist) ● Bat - (Larry Moss) ● Baz -

Spring Summer 2018

A WHOLE WORLD OF FUN! SPRING SUMMER 2018 NEW Croquet Set Perfect for garden parties and summer weddings, our wooden Croquet Set comes with 4 colourful mallets, 6 hoops, 4 balls, stake and cotton bag. Box size: 145 x 718 x 65mm RID319 NEW Hoopla NEW Rounders Set Wooden Hoopla set including a wooden Hit one out of the park with this Rounders target range and 5 rope hoops. Set. Includes wooden bat, 4 wooden base Box size: 110 x 440 x 61mm markers, tennis ball and cotton bag. RID297 Box size: 98 x 610 x 70mm RID323 NEW Boules Set NEW Paddle Ball Set A wooden set of the classic Boules game including Wooden Paddle Ball Set. Includes 2 wooden 6 balls, a jack and cotton bag. paddles, rubber ball and cotton bag. Size: 161 x 201 x 70mm Box size: 238 x 430 x 45mm RID316 RID322 5 HOUSE OF NOVELTIES NEW NEW Tri Blade Boomerang Bright red Tri-Blade Boomerang with stickers for customisation. Box size: 278 x 278 x 5mm RID315 Ridley’s House of Novelties is a registered trademark of Wild & Wolf Ltd. © 2018 Wild & Wolf Ltd. All rights reserved. Ltd. © 2018 Wild & Wolf of Wild & Wolf trademark is a registered House of Novelties Ridley’s For advice and orders visit us online at wildandwolf.co.uk / wildandwolf.eu or call +44 (0) 1225 789909 6 PIGS WILL FLY! NEW Diabolo NEW Novelty Pig Kite Includes 2 wooden hand sticks, string and a Pink Novelty Pig Kite with poles, handle and specially-designed soft rubber Diabolo. -

Thailand Suppliers by Region Ayutthaya (39) Bangkok (4920) Bangkok, Thailand (48) Bkk (157)

Global Suppliers Catalog - Sell147.com 13720 Thailand Suppliers By Region ayutthaya (39) Bangkok (4920) Bangkok, Thailand (48) Bkk (157) Chachoengsao (45) Chanthaburi (30) Chiang Mai (244) Chiangmai (226) chon buri (36) chonburi (309) Lampang (63) Nakornpathom (54) Nonthaburi (401) Pathum Thani (52) Pathumthani (135) Phuket (101) Ratchaburi (44) Rayong (92) Samut Prakan (59) samutprakan (50) Samutprakarn (314) Samutsakhon (49) samutsakorn (135) Saraburi (31) songkhla (68) Suratthani (33) Updated: 2014/11/30 Bangkok Suppliers Company Name Business Type Total No. Employees Year Established Annual Output Value P.K. Trading (Thailand) Co.,LTD Manufacturer 51 - 100 People 2000 - Food,Beverage,Healthy,Furniture,Home Decoration Trading Company Thailand Bangkok Saimai P.T. INTERTRADE Manufacturer - 2014 - Dollhouse,Mango Wood Vase,Taxidermy Trading Company Thailand Bangkok Wee-rin Chemical Thailand Trading Company Chemical,Food Aditives,water theatment,Basic Chemical,Agricultural Chemical Agent 5 - 10 People 2005 - Thailand Bangkok laksri Distributor/Wholesaler LUCKY SPINNING CO. LTD Manufacturer Air Vortex MVS yarn , Cotton Open End, Cotton Ring Carded Combed Slub,Polyest Agent Above 1000 People 2003 - er Poly Viscose Viscose Slub Melange Dyed,Modal Tencel Linen Thermolite ... Distributor/Wholesaler Thailand Bangkok Bangkok CHOTIMA MODA LTD., PART rubber slipper ,beach slipper ,rubber sandal Manufacturer 11 - 50 People 2003 - Thailand Bangkok Jatujak plenstore Manufacturer Asian kitchenware,Asian homeware,Aluminum cups ,Sticky rice basket,hand -

Developing Collaborative & Social Arts Practice

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327207095 Developing Collaborative & Social Arts Practice: The Heart of Glass Research Partnership 2014—2017 Technical Report · August 2018 CITATIONS READS 0 23 4 authors: Alastair Roy Lynn Froggett University of Central Lancashire University of Central Lancashire 51 PUBLICATIONS 162 CITATIONS 96 PUBLICATIONS 391 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Julian Yves Manley John Wainwright University of Central Lancashire University of Central Lancashire 27 PUBLICATIONS 54 CITATIONS 12 PUBLICATIONS 10 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Psychosocial and symbolic dimensions of the breast and breast cancer explored through a visual matrix View project Black families adoption project View project All content following this page was uploaded by Alastair Roy on 28 August 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Executice Summary Developing Collaborative & Social Arts Practice: The Heart of Glass Research Partnership 2014—2017 A study by the Psychosocial Research Unit Alastair Roy, Lynn Froggett, Julian Manley and John Wainwright 1 Heart of Glass Evaluation Report PSYCHOSOCIAL RESEARCH UNIT Heart of Glass Evaluation Report: November 2017 Alastair Roy, Lynn Froggett, Julian Manley and John Wainwright 2 Executice Summary Developing Collaborative & Social Arts Practice: The Heart of Glass Research Partnership 2014—2017 A study by the Psychosocial Research Unit Alastair Roy, Lynn Froggett, Julian Manley and John Wainwright 3 Acknowledgments We are extremely grateful to all those Our thanks also go to the artists, directors and producers whose work has been the subject of this who have supported this evaluation in report including: Joshua Sofaer – Your Name Here, diferent ways. -

Arts/Crafts/Music: Swingball Bead Making Skipping Ropes Jewellery Ma

Appendix 2 Activity Menu: Costs Sports/Physical activiites: Arts/Crafts/Music: Swingball Bead making Skipping ropes Jewellery making Badminton Badge making Football Friendship bracelets Tennis Nail art Space Hoppers Mosaic box making Portable mini bmx ramps Decks/comp's on music bus Kite flying Smoothie drinks making Kwik cricket Fruit Kebabs Unihoc Plant pot decoration Volleyball glass painting Basketball T shirt painting Rounders Pillowslip/tea towel painting picture frame decorating porcelein cup painting Balloon modelling Clay modelling Egg cup/ceramic painting cup cake decorating Total Costs of core offer £4,000 Commissioned Activities Cost and number of session Climbing wall £750 per day x 2 £1,500 Slack Lines £750 per day x 2 £1,500 Gyroscope chair £750 per day x 2 £1,500 Bungee trampoline £750 per day x 2 £1,500 Skate Ramps £750 per day x 2 £1,500 Laser tag £750 per day x 2 £1,500 Land zorbs £750 per day x 2 £1,500 Mountain bike course £600 per day x 3 £1,800 Trampolines £500 per day x 4 £2,000 Animal Experience £200 per day x 6 £1,200 Steel drumming £200 per day x 6 £1,200 African drumming £200 per day x 6 £1,200 Football skills £75 per day x 18 £1,350 Basketball skills £75 per day x 5 £375 Street dance £75 per day x 5 £375 Street art £300 per day x 8 £2,400 Belly dancing £75 per day x 5 £375 Henna Tattoos £75 per day x 5 £375 Flower arranging/floristry £75 per day x 5 £375 Learn to sing £75 per day x 5 £375 Magic and conjouring £75 per day x 5 £375 Hula hooping £75 per day x 5 £375 Appendix 2 Zumba £75 per day x 5 £375 knitting £75 per day x 5 £375 Bouncy Castles/Assault course £500 per day x 29 £14,500 Total cost of commissioned activities £39,900 Locally Commissioned Activities Activities and staffing provided locally from each of the Hubs £2,000 per hub £10,000 Additional Staffing Costs 5 staff for 36 days for 5 hours YSW with on costs per hr: per day at £12 per hour £10,800 Total Total Summer Programme Costs £64,700 Income Community Safety £50,000 Bromley Youth Support Programme Staffing and Resources £15,000 Total Income £65,000. -

July 5 – 7, 2019 · Friday to Sunday · 4Pm – 12Am

FOOD DRINK DESSERTS SNACKS FOOD DRINKS DESSERTS SNACKS 626 NIGHT MARKET vegetarian options available vegan options available JULY 5 – 7, 2019 · FRIDAY TO SUNDAY · 4PM – 12AM E05 A-SHA FOODS USA LUCKY ELEPHANT D33 E47 Boiled Noodle, Chicken, Ground Pork, Tofu, Veggie Topping Lamb Skewers, Squid Cutlet, Hot & Sour Soup, Takoyaki, Chinese Crepe A•J•A•J C A F E D18 LUCKYBALL KOREAN BBQ E67 Skewers, Short Rib/Chicken Bowl, Garlic Noodle, Carne Asada Fries/Nacho, D19 Chicken/Beef/Pork Skewers, Squid Skewers, Foot Long Fries, Bubble Waffle, Funnel Cake, Drinks Blossoming Onion, Fruit Lemonade, Cheese Balls, Volcano Fried Rice STAGE AB SORBETS MAIN CHICK HOT CHICKEN D51 Pre-Packaged Sorbet Filled Fresh Fruit Shells, E48 Main Chick Sandwich, Fries, Chicken Tenders ATM Alcohol Flavored Sorbets, Sparkling Fruit Juices MAIN SQUEEZE E83 KID ZONE 42 25 AIM THAI CUISINE Fruit Flavored Lemonades, Fried Churro EXIT 41 E21 26 Pad Thai, Pad See Ew, Fried Rice, Chow Mein, BBQ Skewers, MASON’S DEN 11 40 27 Egg Rolls, Fried Banana, Boba Drinks E19 12 Corn Cobs & Cup: Hot Cheetos, Cheese Cheetos, Takis, Duritos, Unicorn; Funnel A B 24 13 28 Cakes, Fried Funnel Oreos, Mangoneadas, Watermeloanadas, Aguas Frescas 39 17 23 BAKED DESSERT BAR 14 29 D47 38 16 Cupcakes In A Jar 20 19 18 17 16 15 22 MELO MELO 37 30 15 21 31 EASTENTRANCE E46 36 35 34 33 32 14 BAMBOO GRILL Coconut Jelly w/ Fruits, Mango Roll, Mango River, Dragon Fruit Jelly, Kiwi Jelly 20 T T E ICK ICKE 1 2 3 10 13 T T E51 19 Skewers, Balut, Grilled Jumbo Squid, Pineapple Mango Juice MINIYAKI INFO 18 E62 BBQ OF TIANJIN D11 Steak, Tacoyaki, Sushi Burger & Teas 4 9 ATM 1 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 ATM D30 BBQ Skewers, Pancake Of Chinese, Oden, Fried Buns, Fresh Fruit Ice 5 8 2 MR. -

Nearly New & Pre Loved Table Top Sale Circus Skills

Silver StarSilver Newsletter Star Newsletter Issue Issue 60 60 May May 2015 2015 NEWSLETTER INCORPORATING A NEARLY NEW & PRE LOVED TABLE TOP SALE (BOOKING ESSENTIAL £10 per table) CIRCUS SKILLS WORKSHOP STILT WALKING, BALLOON MODELLING BBQ & CREAM TEAS PLUS LOTS MORE RAFFLE Please fnd rafe tckets enclosed. As usual we have some generously donated prizes. Our twice yearly rafes are a VITAL fundraiser for us and we ask you to take part if you possibly can. Fill in the stubs and return with payment to Maggie in the envelope provided or bring on the day. Please make cheques out to ‘Silver Star Society’ and if you need any more tckets contact Maggie or Clare at the Silver Star ofce. Thank you. Offering special care to mothers with medical complications in pregnancy Silver Star Newsletter Issue 60 May 2015 Contacts & For Yo u r Hospital Charity Information. Abseil Join the Silver Star Society 100 ft at the JR, Oxford, for our To become a member and receive the hospital causes newsleter free of charge, please e mail Maggie See inside for details or Clare on [email protected]. Please be sure to inform us if you would like your Sunday 14th June baby’s name to be included in the newsleter as and Sunday this does not automatcally happen. 20th September Contact Details Maggie Findlay & Clare Edwards Midwives, Amanda and Aletha, Silver Star Society Ofce, Level 6, Women’s celebrate after their abseil. Centre, John Radclife Hospital, Headington, Oxford OX3 9DU. www.hospitalcharity.co.uk e: [email protected] Oxford Radcliffe Hospitals Charitable Funds (registered charity no 1057295) t: 01865 743444 supports the work of the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust Tel.