Identifying Suitable Detection Dogs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hero Dogs White Paper Working Dogs: Building Humane Communities with Man’S Best Friend

Hero Dogs White Paper Working Dogs: Building Humane Communities with Man’s Best Friend INTRODUCTION Humankind has always had a special relationship with canines. For thousands of years, dogs have comforted us, protected us, and given us their unconditional love. Time and time again through the ages they have proven why they are considered our best friends. Yet, not only do dogs serve as our beloved companions, they are also a vital part of keeping our communities healthy, safe and humane. American Humane Association has recognized the significant contributions of working dogs over the past five years with our annual Hero Dog Awards® national campaign. Dogs are nominated in multiple categories from communities across the country, with winners representing many of the working dog categories. The American Humane Association Hero Dog Awards are an opportunity to educate many about the contributions of working dogs in our daily lives. This paper provides further background into their contributions to building humane communities. Dogs have served as extensions of human senses and abilities throughout history and, despite advancements in technology, they remain the most effective way to perform myriad tasks as working dogs. According to Helton (2009a, p. 5), “the role of working dogs in society is far greater than most people know and is likely to increase, not diminish, in the future.” Whether it’s a guide dog leading her sight-impaired handler, a scent detection dog patrolling our airports, or a military dog in a war zone searching for those who wish to do us harm, working dogs protect and enrich human lives. -

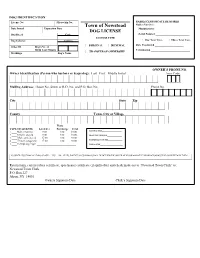

Dog License Application

DOG IDENTIFICATION License No. Microchip No. RABIES CERTIFICATE REQUIRED Rabies Vaccine: Town of Newstead Date Issued Expiration Date Manufacturer __________________________ DOG LICENSE Serial Number __________________________ Dog Breed Code LICENSE TYPE Dog Color(s) Code(s) One Year Vacc. Three Year Vacc. ORIGINAL RENEWAL Date Vaccinated ______________________ Other ID Dog’s Yr. of Birth Last 2 Digits Veterinarian ______________________________ TRANSFER OF OWNERSHIP Markings Dog’s Name OWNER’S PHONE NO. Owner Identification (Person who harbors or keeps dog): Last First Middle Initial Area Code Mailing Address: House No. Street or R.D. No. and P.O. Box No. Phone No. City State Zip County Town, City or Village State TYPE OF LICENSE Local Fee Surcharge Total 1.____Male, neutered 9.00 1.00= 10.00 LICENSE FEE____________________ 2.____Female, spayed 9.00 1.00= 10.00 SPAY/NEUTER FEE_______________ 3.____ Male, unneutered 17.00 3.00= 20.00 4.____ Female, unspayed 17.00 3.00= 20.00 ENUMERATION FEE______________ 5.____Exempt dog Type: ______________________________ TOTAL FEE______________________ _ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ IS OWNER LESS THAN 18 YEARS OF AGE? YES NO IF YES, PARENT Owner’s OR GUARDIANSignature SHALL BE DEEMED THE OWNERDate OF RECORD AND THEClerk’s INFORMATION Signature MUST BE COMPLETEDDate BY THEM. Return form, current rabies certificate, spay/neuter certificate (if applicable) and check made out to “Newstead Town Clerk” to: Newstead Town Clerk P.O. Box 227 Akron, NY 14001 _____________________________________ ___________________________________________ Owners Signature/Date Clerk’s Signature/Date OWNER’S INSTRUCTIONS 1. All dogs 4 months of age or older are to be licensed. In addition, any dog under 4 months of age, if running at large must be licensed. -

An Examination of the Training and Reliability of the Narcotics Detection Dog Robert C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Kentucky Kentucky Law Journal Volume 85 | Issue 2 Article 4 1996 An Examination of the Training and Reliability of the Narcotics Detection Dog Robert C. Bird Boston University Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Bird, Robert C. (1996) "An Examination of the Training and Reliability of the Narcotics Detection Dog," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 85 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol85/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Examination of the Training and Reliability of the Narcotics Detection Dog BY ROBERT C. BIRD* INTRODUCTION Dunng the past twenty years, the United States has been fight- mg one of the most difficult wars in its history- the war on drugs.' The narcotics detection dog has been a stalwart ally in that conflict, detecting illegal narcotics on countless occasions.2 Canine * Law Clerk, Massachusetts Superior Court 1996-97; M.B.A. Candidate, Boston University; J.D. 1996, Boston University School of Law. My thanks for comments and support to members of the Suffolk University 1996 Annual Convocation for Law Students: "Law In a Changing Society," at which I presented an earlier version of tis Article. -

Dog” Looks Back at “God”: Unfixing Canis Familiaris in Kornél Mundruczó’S † Film Fehér Isten/White God (2014)

humanities Article Seeing Beings: “Dog” Looks Back at “God”: Unfixing Canis familiaris in Kornél Mundruczó’s † Film Fehér isten/White God (2014) Lesley C. Pleasant Department of Foreign Languages and Cultures, University of Evansville, Evansville, IN 47714, USA; [email protected] † I have had to rely on the English subtitles of this film, since I do not speak Hungarian. I quote from the film in English, since the version to which I have had access does not give the option of Hungarian subtitles. Received: 6 July 2017; Accepted: 13 October 2017; Published: 1 November 2017 Abstract: Kornél Mundruczó’s film Fehér isten/White God (2014) portrays the human decreed options of mixed breed, abandoned dogs in the streets of Budapest in order to encourage its viewers to rethink their relationship with dogs particularly and animals in general in their own lives. By defamiliarizing the familiar ways humans gaze at dogs, White God models the empathetic gaze between species as a potential way out of the dead end of indifference and the impasse of anthropocentric sympathy toward less hierarchical, co-created urban animal publics. Keywords: animality; dogs; film; White God; empathy 1. Introduction Fehér isten/White God (2014) is not the first film use mixed breed canine actors who were saved from shelters1. The Benji films starred mixed breed rescued shelter dogs (McLean 2014, p. 7). Nor is it unique in using 250 real screen dogs instead of computer generated canines. Disney’s 1996 101 Dalmations starred around 230 Dalmation puppies and 20 adult Dalmations (McLean 2014, p. 20). It is also certainly not the only film with animal protagonists to highlight Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody # 2 in its soundtrack. -

V E R S a T I L E It's a Brave New World! SPECIAL PUPPY ISSUE

VERSATILE HUNTING DOG A Publication of The North American Versatile Hunting Dog Association • Volume XLIX • No. 5 • May 2018 It’s A Brave New World! SPECIAL PUPPY ISSUE VERSATILE IF SOMEONE HUNTING DOG Volume XLIX • No. 5 • May 2018 NAVHDA International Officers & Directors David A. Trahan President TOLD YOU THAT Bob Hauser Vice President Steve J. Greger Secretary Richard Holt Treasurer Chip Bonde Director of Judge Development Andy Doak Director of Promotions FEATURES Tim Clark Director of Testing Tim Otto Director of Publications Steve Brodeur Registrar 4 It’s A Brave New World! • by Judy Zeigler Tracey Nelson Invitational Director Marilyn Vetter Past President 8 Sporting Breeds In Demand For Explosives Detection Work • by Penny Leigh Versatile Hunting Dog Publication Staff 14 The Healing • by Kim McDonald Mary K. Burpee Editor/Publisher Erin Kossan Copy Editor Sandra Downey Copy Editor 18 Anything & Everything • by Patti Carter Rachael McAden Copy Editor Patti Carter Contributing Editor Dr. Lisa Boyer Contributing Editor 22 We Made It Through • by Penny Wolff Masar 9191 Nancy Anisfield Contributing Editor/Photographer Philippe Roca Contributing Editor/Photographer 29 It’s Not Always Easy • by Patti Carter Wight Greger Women’s Editor Dennis Normile Food Editor 30 Test Prep Workshop • by Nancy Anisfield OF THE TOP 100 Maria Bondi Advertising Coordinator Marion Hoyer Webmaster Advertising Information DEPARTMENTS Copy deadline: 45 days prior to the month of President’s Message • 2 18 SPORTING publication. Commercial rates available upon request. All inquiries or requests for advertising should be On The Right Track • 4 * addressed to: Spotlight Dog • 25 DOGS EAT THE SAME NAVHDA PO Box 520 Ask Dr. -

Wildlife Detector-Dog and Inspector Training Program Q & As

Wildlife Detector-Dog and Inspector Training Program Q & As 1. Why are you developing this detector-dog program? Illegal trafficking in animals, animal parts and plants is contributing to the dramatic decline of many species in the wild. Animals such as elephants and rhinos are in serious danger of extinction due to poaching to supply the black market for ivory and rhino horn. 2. How will the dogs help? The ability of dogs to sniff out hidden wildlife products can greatly increase our detection coverage at high volume ports such as Miami, Chicago, Louisville, and Los Angeles. The Service has seen the great work the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Customs and Border Protection have done with their canine teams and we believe the Wildlife Detector-Dog program will bring us similar, much-needed success. 3. What good will it do? The program will enable a significant increase in our inspection capabilities. In a fraction of the time it takes a human inspector to examine a hundred or so packages, a dog can sniff literally thousands of packages or items of luggage on a conveyor belt. 4. Are there alternatives? Due to the sequester, we won’t be able to fill wildlife inspector vacancies or hire additional inspectors to help stem illegal trade in protected species, though we hope that will be an option once again in the future. Experimenting with the use of wildlife detector dogs should prove to be an effective alternative staff multiplier for us in the battle to combat illegal wildlife trafficking. 5. How much does it cost? For the pilot program, we’re moving existing staff into these positions so there’s no additional personnel cost. -

Rescued Dogs Help Game Wardens in the War Against Wildlife Criminals

In a test of their field search skills, warden Lori Oldfather and detection-dog-in-training Jin uncover a hidden squirrel carcass. O N THE SCENT OF Rescued dogs help game wardens in the war against wildlife criminals BY JULIE FALCONER By mid-afternoon on training day , the smell of decaying body parts starts to waft through the sprawling warehouse, an equipment depot at the California Department of Fish and Game’s regional office in Rancho Cordova. A strong breeze blowing through a gap under the south-side door passes over a plastic bucket with aging abalone, moves through the wooden pallets covering recently collected roadkill, and circulates to the opposite end of the building where a search is about to begin. Rookie-in-training Jin has spent the morning outside, bouncing in and out of nearly a dozen watercraft in pursuit of invasive quagga and zebra mussels. Even so, the lanky yellow Labrador exudes intense energy, haunches vibrating with the effort to sit still. At the other end of the leash, game warden Lori Oldfather is also excited—and anxious for her partner to pass this hurdle to becoming a certified detection dog. At a signal from the judge, warden and dog stride briskly across the concrete floor and down aisles bisected by towering wooden shelves, retired office furniture, and a sporting goods store’s worth of outdoor gear. They work side by side in a methodical pattern that tests Oldfather’s investigative skills as much as Jin’s olfactory talents. When the dog shows interest in an area that turns up empty, her handler must calculate where the odor has originated and guide the search to those spots. -

RA Nyctereutes Procyonoides

ELGIUM B NATIVE ORGANISMS IN ORGANISMS NATIVE - Risk analysis of the RAPPORTS -ETUDES Ressources naturelles Raccoon dog Nyctereutes procyonoides ISK ANALYSIS REPORT OF NON REPORT OF ANALYSIS ISK R Risk analysis report of non-native organisms in Belgium Risk analysis of the raccoon dog Nyctereutes procyonoides (Gray, 1834) Evelyne Baiwy (1) , Vinciane Schockert (1) & Etienne Branquart (2) (1) Unité de Zoogéographie, Université de Liège (2) Cellule interdépartementale Espèces invasives, Service Public de Wallonie Adopted in date of: 11 th March 2013 Reviewed by : René-Marie Lafontaine (RBINS) & Koen Van Den Berge (INBO) Produced by: Unité de Zoogéogaphie/Université de Liège & Cellule interdépartementale Espèces invasives (CiEi)/DEMNA/DGO3 Commissioned by: Service Public de Wallonie Contact person: [email protected] This report should be cited as : “Baiwy, E., Schockert, V. & Branquart, E. (2013) Risk analysis of the raccoon dog Nyctereutes procyonoides, Risk analysis report of non-native organisms in Belgium. Cellule interdépartementale sur les Espèces invasives (CiEi), DGO3, SPW / Editions, 37 pages”. Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... 1 Executive summary ...................................................................................................................... 4 Résumé ....................................................................................................................................... -

CFSG Guidance on Dog Conformation Acknowledgements with Grateful Thanks To: the Kennel Club, Battersea (Dogs & Cats Home) & Prof

CFSG Guidance on Dog Conformation Acknowledgements With grateful thanks to: The Kennel Club, Battersea (Dogs & Cats Home) & Prof. Sheila Crispin MA BScPhD VetMB MRCVS for providing diagrams and images Google, for any images made available through their re-use policy Please note that images throughout the Guidance are subject to copyright and permissions must be obtained for further use. Index 1. Introduction 5 2. Conformation 5 3. Legislation 5 4. Impact of poor conformation 6 5. Conformation & physical appearance 6 Eyes, eyelids & area surrounding the eye 7 Face shape – flat-faced (brachycephalic) dog types 9 Mouth, dentition & jaw 11 Ears 12 Skin & coat 13 Back, legs & locomotion 14 Tail 16 6. Summary of Key Points 17 7. Resources for specific audiences & actions they can take to support good dog conformation 18 Annex 1: Legislation, Guidance & Codes of Practice 20 1. Legislation in England 20 Regulations & Guidance Key sections of Regulations & Guidance relevant to CFSG sub-group on dog conformation Overview of the conditions and explanatory guidance of the Regulations 2. How Welfare Codes of Practice & Guidance support Animal Welfare legislation 24 Defra’s Code of Practice for the Welfare of Dogs Animal Welfare Act 2006 Application of Defra Code of Practice for the Welfare of Dogs in supporting dog welfare 3. The role of the CFSG Guidance on Dog Conformation in supporting dog welfare 25 CFSG Guidance on Dog Conformation 3 Annex 2: Key points to consider if intending to breed from or acquire either an adult dog or a puppy 26 Points -

Dog License Application Months, a Pro-Rated Fee Is Available If • When the Dog Has Its Adult Canine Teeth Or Licensing in Person at the Sheriff’S Office

When is my dog required to be licensed? If the rabies certificate expires in less than 12 Dog License Application months, a pro-rated fee is available if • When the dog has its adult canine teeth or licensing in person at the Sheriff’s Office. Please Print is six months of age, whichever comes Note: Fees are subject to change without notice. first, or Last Name _____________________________________ First Name _____________________________________ • Within 30 days of becoming the owner or Late Fees keeper of the dog, or In addition to the licensing fees listed above, Street Address _________________________________ • Within 30 days of moving into the following are the late penalties per dog for failure to County. purchase a dog license as required: City _____________________________ Zip Code ________________ What documents are required for 1. Voluntary Licensing (the owner or keeper voluntarily licenses) : $10 licensing? Mailing Address ____________________________________ 2. Non-voluntary Licensing $50 City _____________________________ A valid rabies vaccination certificate issued This is licensing that occurs as a result and signed by a licensed veterinarian. Rabies of impoundment of the dog, offenses Zip Code ________________ certificates must be valid for the duration of the occurring off the owner’s property, licensing period. and/or other offenses specified in county ordinance. Home Phone ___________________________________ A certificate of sterilization to receive the Cell Phone ___________________________________ spay/neuter “altered” rate if not indicated on In addition to the late fee, each dog the rabies vaccination certificate. owned, kept, or impounded must be Other Phone ___________________________________ If your dog was impounded at the Willamette micro-chipped and registered with an Humane Society, include the pink copy of approved national database. -

The Intelligence of Dogs a Guide to the Thoughts, Emotions, and Inner Lives of Our Canine

Praise for The Intelligence of Dogs "For those who take the dog days literally, the best in pooch lit is Stanley Coren’s The Intelligence of Dogs. Psychologist, dog trainer, and all-around canine booster, Coren trots out everyone from Aristotle to Darwin to substantiate the smarts of canines, then lists some 40 commands most dogs can learn, along with tests to determine if your hairball is Harvard material.” —U.S. News & World Report "Fascinating . What makes The Intelligence of Dogs such a great book, however, isn’t just the abstract discussions of canine intelli gence. Throughout, Coren relates his findings to the concrete, dis cussing the strengths and weaknesses of various breeds and including specific advice on evaluating different breeds for vari ous purposes. It's the kind of book would-be dog owners should be required to read before even contemplating buying a dog.” —The Washington Post Book World “Excellent book . Many of us want to think our dog’s persona is characterized by an austere veneer, a streak of intelligence, and a fearless-go-for-broke posture. No matter wrhat your breed, The In telligence of Dogs . will tweak your fierce, partisan spirit . Coren doesn’t stop at intelligence and obedience rankings, he also explores breeds best suited as watchdogs and guard dogs . [and] does a masterful job of exploring his subject's origins, vari ous forms of intelligence gleaned from genetics and owner/trainer conditioning, and painting an inner portrait of the species.” —The Seattle Times "This book offers more than its w7ell-publicized ranking of pure bred dogs by obedience and working intelligence. -

The Cocker Spaniel by Sharon Barnhill

The Cocker Spaniel By Sharon Barnhill Breed standards Size: Shoulder height: 38 - 41 cm (15 - 16.5 inches). Weight is around 29 lbs. Coat: Hair is smooth and medium length. Character: This dog is intelligent, cheerful, lively and affectionate. Temperament: Cocker Spaniels get along well with children, other dogs, and any household pets. Training: Training must be consistent but not overly firm, as the dog is quite willing to learn. Activity: Two or three walks a day are sufficient. However, this breed needs to run freely in the countryside on occasion. Most of them love to swim. Cocker spaniel refers to two modern breeds of dogs of the spaniel dog type: the American Cocker Spaniel and the English Cocker Spaniel, both of which are commonly called simply Cocker Spaniel in their countries of origin. It was also used as a generic term prior to the 20th century for a small hunting Spaniel. Cocker spaniels were originally bred as hunting dogs in the United Kingdom, with the term "cocker" deriving from their use to hunt the Eurasian Woodcock. When the breed was brought to the United States it was bred to a different standard which enabled it to specialize in hunting the American Woodcock. Further physical changes were bred into the cocker in the United States during the early part of the 20th century due to the preferences of breeders. Spaniels were first mentioned in the 14th century by Gaston III of Foix-Béarn in his work the Livre de Chasse. The "cocking" or "cocker spaniel" was first used to refer to a type of field or land spaniel in the 19th century.