A New Approach to Infrastructure Planning at the 2018 Gold Coast Commonwealth Games?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Bash League 2018-19 Fixtures

Big Bash League 2018-19 Fixtures DATE TIME MATCH FIXTURE VENUE 19 December 18:15 Match 1 Brisbane Heat v Adelaide Strikers The Gabba 20 December 19:15 Match 2 Melbourne Renegades v Perth Scorchers Marvel Stadium 21 December 19:15 Match 3 Sydney Thunder v Melbourne Stars TBD 22 December 15:30 Match 4 Sydney Sixers v Perth Scorchers SCG 18:00 Match 5 Brisbane Heat v Hobart Hurricanes Carrara Stadium 23 December 18:45 Match 6 Adelaide Strikers v Melbourne Renegades Adelaide Oval 24 December 15:45 Match 7 Hobart Hurricanes v Melbourne Stars Bellerive Oval 19:15 Match 8 Sydney Thunder v Sydney Sixers Spotless Stadium 26 December 16:15 Match 9 Perth Scorchers v Adelaide Strikers Optus Stadium 27 December 19:15 Match 10 Sydney Sixers v Melbourne Stars SCG 28 December 19:15 Match 11 Hobart Hurricanes v Sydney Thunder Bellerive Oval 29 December 19:00 Match 12 Melbourne Renegades v Sydney Sixers Docklands 30 December 19:15 Match 13 Hobart Hurricanes v Perth Scorchers York Park 31 December 18:15 Match 14 Adelaide Strikers v Sydney Thunder Adelaide Oval 1 January 13:45 Match 15 Brisbane Heat v Sydney Sixers Carrara Stadium 19:15 Match 16 Melbourne Stars v Melbourne Renegades MCG 2 January 19:15 Match 17 Sydney Thunder v Perth Scorchers Spotless Stadium 3 January 19:15 Match 18 Melbourne Renegades v Adelaide Strikers TBC 4 January 19:15 Match 19 Hobart Hurricanes v Sydney Sixers Bellerive Oval 5 January 17:15 Match 20 Melbourne Stars v Sydney Thunder Carrara Stadium 18:30 Match 21 Perth Scorchers v Brisbane Heat Optus Stadium 6 January 18:45 Match -

Metricon Stadium Steel Awards 2012 Winner Case Study

METRICON STADIUM STEEL AWARDS 2012 WINNER CASE STUDY LARGE PROJECT AWARD 2012 STATE WINNER (QLD) ENGINEERING PROJECTS WINNER (QLD) ARCHITECTURAL MERIT individual element failing. The project was a redevelopment project compromising of a Laminated glass photovoltaic cells were incorporated into the significant reconfiguration and a complete renovation of the roof to capitalise on the stadium’s vast roof surface as an energy existing Carrara Stadium. The 25 000 seat Metricon Stadium source. will be the new home for the Gold Coast Suns and the poten- tial main stadium for the Gold Coast’s 2018 Commonwealth The stadium has a lightweight tension Games. Working to a tight program, Arup’s core team of expe- membrane roof, utilising optimised slender rienced stadium engineers helped deliver the $144m stadium within an 18 month construction period. steel members with a benchmark weight of around 40kg per square metre. The stadium has a lightweight tension membrane roof, utilising optimised slender steel members. Arup utilised in-house form INNOVATION IN THE USE OF STEEL finding software and applied experience gained from the design of other iconic fabric canopies. This experience, The architects and engineers worked closely through the combined with the ability to interact and collaborate with wind concept phase of the project in order to establish and design a engineers and the architect, rapidly improved the reliability solution which is both aesthetically pleasing and cost-effective. of initial design concepts for the fabric shapes and early steel This was particularly challenging given the reasonably tight structure estimates. project budget and fast tracked construction program. The resulting design was a curved membrane The result, which met the time and budget criteria, was a roof form supported via curved members, curved membrane roof form supported via curved CHS mem- bers, in turn supported via simple planar CHS trusses on a large which are in turn supported by planar trusses. -

Capital Statement Capital

3 Budget Paper No. Paper Budget budget.qld.gov.au Capital Statement Capital Queensland Budget 2018–19 Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 3 budget.qld.gov.au Queensland Budget 2018–19 Budget Queensland Capital Statement Budget Paper No. Paper Budget Statement Capital 2018–19 Queensland Budget Papers 1. Budget Speech 2. Budget Strategy and Outlook 3. Capital Statement 4. Budget Measures 5. Service Delivery Statements Appropriation Bills Budget Highlights The Budget Papers are available online at budget.qld.gov.au © Crown copyright All rights reserved Queensland Government 2018 Excerpts from this publication may be reproduced, with appropriate acknowledgement, as permitted under the Copyright Act. Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 ISSN 1445-4890 (Print) ISSN 1445-4904 (Online) Queensland Budget 2018–19 Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 Capital Statement 2018-19 Contents 1 Approach and highlights ....................................... 1 Features .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 2 1.2 Capital planning and prioritisation ...................................................................................... 3 1.3 Innovative funding and financing ....................................................................................... 4 1.4 Key projects ...................................................................................................................... -

AFL D Contents

Powering a sporting nation: Rooftop solar potential for AFL d Contents INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................................1 AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE ...................................................................................... 3 AUSTRALIAN RULES FOOTBALL TEAMS SUMMARY RESULTS ........................4 Adelaide Football Club .............................................................................................................7 Brisbane Lions Football Club ................................................................................................ 8 Carlton Football Club ................................................................................................................ 9 Collingwood Football Club .................................................................................................. 10 Essendon Football Club ...........................................................................................................11 Fremantle Football Club .........................................................................................................12 Geelong Football Club .............................................................................................................13 Gold Coast Suns ..........................................................................................................................14 Greater Western Sydney Giants .........................................................................................16 -

Competition Events Schedule

Competition Events Schedule A full schedule for every event is available at gc2018.com/tickets Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 April GC2018.com/tickets Opening Ceremony Carrara Stadium Closing Ceremony Carrara Stadium Athletics Track & field Carrara Stadium Race walks Currumbin Beachfront Marathon Southport Broadwater Parklands Badminton Carrara Sports and Leisure Centre Basketball Preliminary Cairns Cairns Convention Centre Preliminary Townsville Townsville Entertainment and Convention Centre Finals Gold Coast Convention and Exhibition Centre Beach Volleyball Coolangatta Beachfront Boxing Oxenford Studios Cycling Mountain Bike Nerang Mountain Bike Trails Road Race Currumbin Beachfront TimeTrial Currumbin Beachfront Track Brisbane Anna Meares Velodrome Diving Gold Coast Aquatic Centre Gymnastics Artistic Coomera Indoor Sports Centre Rhythmic Coomera Indoor Sports Centre Hockey Gold Coast Hockey Centre Lawn Bowls Broadbeach Bowls Club Netball Preliminary Gold Coast Convention and Exhibition Centre Finals Coomera Indoor Sports Centre Para Powerlifting Carrara Sports and Leisure Centre Rugby Sevens Robina Stadium Shooting Brisbane Belmont Shooting Centre Squash Oxenford Studios Swimming Gold Coast Aquatic Centre Table Tennis Oxenford Studios Triathlon Southport Broadwater Parklands Weightlifting Carrara Sports and Leisure Centre Wrestling Carrara Sports and Leisure Centre Competition event schedule is subject to change, stay up-to-date by visiting gc2018.com A full Competition Event Schedule -

2014 NRL Year Book

NRL Referees Col Pearce Medal 2014 WELCOME Welcome to the 2014, 11th annual awarding of refereeing’s most prestigious prize, the Col Pearce Medal, which occurs at the culmination of the closest NRL season in history. As we are all aware, the closer any competition is, the greater the level of scrutiny on match officials and their performances. This season has been no different. The start of the season witnessed a new manager of the squad with Daniel Anderson moving to take up an opportunity as the General Manager of Football at Parramatta. As with any change of leadership this brings some level of apprehension and concern. All officials should be very proud of their efforts, dedication and commitment to the season. At the season launch early this year, I spoke about these qualities and I am confident to say that those in the squad delivered on them. For that I thank you. No official is successful without the wonderful support of their family and close friends. I thank all the partners for the support in the endless hours that the referees were away from home. Additionally, for those times when they were at home but distracted by the demands of officiating at the elite level. I would like to take this opportunity to thank my staff for their unbelievable support and hard work throughout the season. Your contribution to the success of the squad this year is immeasurable. As in any season, individuals and the group have had highs and lows but one of the most significant improvements was the level of support that the NRL Referee squad received from the NRL hierarchy including Nathan McGuirk, Todd Greenberg and Dave Smith as well as the NRL Commission. -

Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 Budget Paper No.3

SPINE WIDTH FROM RIGHT CENTRE TEXT Queensland Budget 2016-17 Capital 2016-17 Budget Queensland Statement Queensland Budget 2016-17 Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 Budget Paper No.3 Paper Budget Queensland Budget 2016-17 Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 www.budget.qld.gov.au 2016-17 Queensland Budget Papers 1. Budget Speech 2. Budget Strategy and Outlook 3. Capital Statement 4. Budget Measures DELETE MAGENTA 5. Service Delivery Statements Appropriation Bills Budget Highlights MARKS ON IFC The Budget Papers are available online at www.budget.qld.gov.au © Crown copyright All rights reserved Queensland Government 2016 Excerpts from this publication may be reproduced, with appropriate acknowledgement, as permitted under the Copyright Act. Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 ISSN 1445-4890 (Print) ISSN 1445-4904 (Online) Queensland Budget 2016-17 Capital Statement Budget Paper No.3 www.budget.qld.gov.au State Budget 2016-17 Capital Statement Budget Paper No. 3 Contents 1 Overview .................................................................. 1 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 2 1.2 Capital purchases .............................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Capital grants ..................................................................................................................... 7 2 State capital program – planning and priorities 10 2.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... -

Sydney Football Stadium Redevelopment

SYDNEY FOOTBALL STADIUM REDEVELOPMENT STATE SIGNIFICANT DEVELOPMENT APPLICATION Concept Proposal and Stage 1 Demolition SSDA 9249 APPENDIX N: Environmentally Sustainable Design Strategy and Statement for Demolition Sydney Football Stadium Redevelopment Environmentally Sustainable Design Strategy Infrastructure NSW Reference: 501857 Revision: 1 11 May 2018 Document control record Document prepared by: Aurecon Australasia Pty Ltd ABN 54 005 139 873 Level 5, 116 Military Road Neutral Bay NSW 2089 PO Box 538 Neutral Bay NSW 2089 Australia T +61 2 9465 5599 F +61 2 9465 5598 E [email protected] W aurecongroup.com A person using Aurecon documents or data accepts the risk of: a) Using the documents or data in electronic form without requesting and checking them for accuracy against the original hard copy version. b) Using the documents or data for any purpose not agreed to in writing by Aurecon. Document control Report title Environmentally Sustainable Design Strategy Document ID Project number 501857 File path Client Infrastructure NSW Client contact David Riches Client reference Rev Date Revision details/status Author Reviewer Verifier Approver (if required) 0 5 April 2018 DRAFT for comment ZK QJ QJ 1 11 May 2018 Issue to client ZK QJ QJ Current revision 1 Approval Author signature Approver signature Name Zofia Kuypers Name Quentin Jackson Title Senior ESD Consultant Title Associate Project 501857 File 180528 SFS ESD Strategy.docx 11 May 2018 Revision 1 Contents 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... -

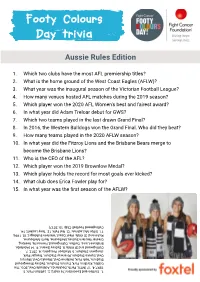

Aussie Rules Edition

Footy Colours Day trivia Aussie Rules Edition 1. Which two clubs have the most AFL premiership titles? 2. What is the home ground of the West Coast Eagles (AFLW)? 3. What year was the inaugural season of the Victorian Football League? 4. How many venues hosted AFL matches during the 2019 season? 5. Which player won the 2020 AFL Women’s best and fairest award? 6. In what year did Adam Treloar debut for GWS? 7. Which two teams played in the last drawn Grand Final? 8. In 2016, the Western Bulldogs won the Grand Final. Who did they beat? 9. How many teams played in the 2020 AFLW season? 10. In what year did the Fitzroy Lions and the Brisbane Bears merge to become the Brisbane Lions? 11. Who is the CEO of the AFL? 12. Which player won the 2019 Brownlow Medal? 13. Which player holds the record for most goals ever kicked? 14. What club does Erica Fowler play for? 15. In what year was the first season of the AFLW? Collingwood Football Club; 15. 2017) 15. Club; Football Collingwood 11. Gillon McLachlan; 12. Nat Fyfe; 13. Tony Lockett; 14. 14. Lockett; Tony 13. Fyfe; Nat 12. McLachlan; Gillon 11. Richmond, St Kilda, West Coast, Western Bulldogs); 10. 1996; 1996; 10. Bulldogs); Western Coast, West Kilda, St Richmond, Greater Western Sydney, Melbourne, North Melbourne, Melbourne, North Melbourne, Sydney, Western Greater Brisbane Lions, Carlton, Collingwood, Fremantle, Geelong, Geelong, Fremantle, Collingwood, Carlton, Lions, Brisbane Collingwood and St Kilda; 8. Sydney Swans; 9. 14 (Adelaide, (Adelaide, 14 9. Swans; Sydney 8. -

2017 the 2017 FFA Cup Delivered More Goals Than Ever, Well Above the Scoring Rate of the A-League, Which Is Already High Amongst Leagues Globally

G T H E I N T P L R A O Y P E P R U S The PFA S B E U M I L A D G I N E FFA Cup G T H Report 2017 A F P F F A E C H U T P R E P O R T 2 0 7 About this 1 Report Last year, the PFA delivered its inaugural FFA Cup Report, highlighting trends from the first three editions of the competition. The PFA has again partnered with Australian football statistician Andrew Howe to update the data for the fourth FFA Cup and introduce new analyses of crowds and player movements between A-League and NPL clubs. The FFA Cup has captured Australia’s imagination by creating a footprint that is truly national in its breadth and uniquely inclusive in its depth. As discussions advance regarding the urgent need to expand the professional footprint in Australia, the FFA Cup provides a valuable touchstone when approaching the logistical, architectural and geographical questions that need to be asked. We believe it is therefore critical to produce research such as this to ensure future discourse is supported by data and evidence. The PFA believes a better-informed game leads to more impactful football education, analysis and decision-making. The FFA Cup has captured Australia’s imagination by creating a footprint that is truly national in its breadth and uniquely inclusive in its depth. 2 FFA Cup Report 2017 4 8 Participation Cup Runs 5 9 Goals and Player Analysis - Competitiveness Age 6 10 Member Federation Player Analysis - Performance Pathways 7 11 Contents Cupsets Crowds 7 Away Performance 3 FFA Cup Report 2017 Participation TOTAL NUMBER OF CLUBS* TOTAL NUMBER OF MATCHES 2014 2015 2014 2015 589 636 604 635 2016 2017 2016 2017 687 720 683 716 *Clubs that played in an FFA Cup match. -

CAPABILITY STATEMENT 2020 COMPANY PROFILE JVG Sound Lighting & Visual Pty Ltd Prides Itself on Its Professionalism and the Quality of Its Business and Services

CAPABILITY STATEMENT 2020 COMPANY PROFILE JVG Sound Lighting & Visual Pty Ltd prides itself on its professionalism and the quality of its business and services. Our company specialises in the design, supply, installation, hire and maintenance of pro audio / public address, stage / theatre / architectural lighting, visual displays, MATV, staging, security, integration / automation, special effects and noise control equipment. JVG Sound began operating over 20 years ago on the Gold Coast, QLD, Australia and has since expanded to meet the growing needs of clients in various locations. Market segments include government projects, casinos, airports, hospitality, entertainment, education, commercial construction, sporting centres, hospitals, houses of worship and high-end residential. JVG Sound is dedicated to providing the very best in multimedia and automation solutions to suit clients’ requirements and budgets. We choose to use products for their quality, technology, safety and reliability. The combination of quality products, an experienced team of professionals and a passion for integrated AV ensures JVG Sound meets and surpasses client expectations. GENERAL SERVICES • Pro Audio: Design, Supply & Installation • Stage Lighting: DMX, Theatre & Nightclub • Digital Signage: Interactive, Kiosk, Wayfinder, Billboards, Menus & more • Architectural Lighting: High Rise, Bridges, Clubs, Hotels & Landscape • Automation/Integration Systems: Commercial & Residential • Security Systems: CCTV, Alarm, Facial Recognition & Access Control • Professional -

Cairns Convention Centre Refurbishment & Expansion Project

Cairns Convention Centre Refurbishment & Expansion Project Industry Briefing Summary The following document provides a short overview of topics covered at the Cairns Convention Centre Industry Briefing hosted by Lendlease Building on Thursday 23 January 2020. PROJECT OVERVIEW & SCOPE Client: Department of Housing and Public Works, Queensland Government Managing Contractor: Lendlease Building Contract Type: Managing Contractors, Design and Construction Management (Two-Stage) Project Budget: $176M Design Status: 80% Design Development (As at 30 Jan 2020) Consultants: • Architectural – COX & CA Architects • Hydraulics & VT – Aecom • Structural – Arcadis • F&B – Food Services Australia • Civil – Arup • AV – Aurecon • Mechanical – McClintock • Certifier – McKenzies • Electrical – Sequel • Landscape – LA3 • Fire – NDY CONSTRUCTION PROGRAM The project will comprise of three key areas: 1. Essential Works • Roof Sheeting Replacement • Replacement of Major Mechanical Plant • Upgrade of Electrical Services • Audio Visual Installation replacement • DDA Upgrade Works 2. Refurbishment Works • Front of house public spaces upgrades • Patron amenities improvements • Food and beverage facilities, including kitchen upgrades • Back of House Operational Areas 3. Expansion Works • New facilities at the Wharf Street end of the Centre, including a 450-seat flat floor plenary space • Three meeting rooms • Exhibition space • Sky Terrace Banquet facilities • Associated Patron and Operational facilities to enable concurrent conventions to occur within the Centre