Complete Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Channel Guide 424 NFL Redzone HD

ADD TO YOUR PACKAGE for an additional fee A LA CARTE 124 NFL RedZone Channel Guide 424 NFL RedZone HD COLLEGE SPORTS PACK 23 SEC Network 127 Fox College Sports (Atlantic) 30 ESPNU 128 Fox College Sports (Pacific) 32 Outdoor Channel 129 Fox College Sports (Central) 33 Sportsman Channel PREMIUM CHANNELS 500 HBO 503 HBO Family HBO 501 HBO 2 504 HBO Comedy 502 HBO Signature 505 HBO Zone 550 Cinemax 554 Movie MAX 551 More MAX 555 Cinemax Latino Cinemax 552 Action MAX 556 5StarMAX 553 Thriller MAX 557 OuterMAX 560 SHOWTIME Family Zone 561 SHOWTIME 2 567 SHOWTIME 562 SHOWTIME BET Women 563 SHOWTIME 570 TMC Extreme Showtime 571 TMC Extra 564 SHOWTIME x 572 FLIX BET 565 SHOWTIME Next 566 SHOWTIME 581 STARZ 592 STARZ ENCORE 582 STARZ in Black Classic 583 STARZ Kids & 593 STARZ ENCORE Family Suspense Starz/ 584 STARZ Edge 594 STARZ ENCORE Encore 585 STARZ Cinema Black 586 STARZ Comedy 595 STARZ ENCORE 590 STARZ ENCORE Westerns 591 STARZ ENCORE 596 STARZ ENCORE Action Family AcenTek Video is not available in all areas. Programming is subject to change without notice. All channels not available to everyone. Additional charges may apply to commercial GRAND RAPIDS DMA PREMIUM HD CHANNELS customers for some of the available channels. For assistance 700 HBO HD 781 STARZ HD call Customer Service at 616.895.9911. 750 Cinemax HD 790 STARZ ENCORE HD Revised 8/30/21 760 Showtime HD 6568 Lake Michigan Drive | PO Box 509 | Allendale, MI 49401 AcenTek.net BASIC VIDEO Basic Video is available in Standard or High Definition. -

The Perceived Credibility of Professional Photojournalism Compared to User-Generated Content Among American News Media Audiences

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE August 2020 THE PERCEIVED CREDIBILITY OF PROFESSIONAL PHOTOJOURNALISM COMPARED TO USER-GENERATED CONTENT AMONG AMERICAN NEWS MEDIA AUDIENCES Gina Gayle Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Gayle, Gina, "THE PERCEIVED CREDIBILITY OF PROFESSIONAL PHOTOJOURNALISM COMPARED TO USER-GENERATED CONTENT AMONG AMERICAN NEWS MEDIA AUDIENCES" (2020). Dissertations - ALL. 1212. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/1212 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This study examines the perceived credibility of professional photojournalism in context to the usage of User-Generated Content (UGC) when compared across digital news and social media platforms, by individual news consumers in the United States employing a Q methodology experiment. The literature review studies source credibility as the theoretical framework through which to begin; however, using an inductive design, the data may indicate additional patterns and themes. Credibility as a news concept has been studied in terms of print media, broadcast and cable television, social media, and inline news, both individually and between genres. Very few studies involve audience perceptions of credibility, and even fewer are concerned with visual images. Using online Q methodology software, this experiment was given to 100 random participants who sorted a total of 40 images labeled with photographer and platform information. The data revealed that audiences do discern the source of the image, in both the platform and the photographer, but also take into consideration the category of news image in their perception of the credibility of an image. -

Wfaa-Tv Eeo Public File Report I. Vacancy List

Page: 1/17 WFAA-TV EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT March 21, 2018 - March 20, 2019 I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the "Master Recruitment Source List" ("MRSL") for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources ("RS") RS Referring Job Title Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree 1-2, 4-5, 7-10, 12-16, 18-20, 24, 26-27, Broadcast & Digital Sports Content Producer 15 30, 33-36, 38, 40-54, 56, 58 2, 4, 7-10, 12-14, 16, 18-20, 24, 26-27, Social Media Reporter 40 30, 33-36, 38, 40-54, 56, 58 1-2, 4-5, 7-10, 12-14, 16, 18-20, 24, 26, Marketing Producer 40 33-36, 38, 40-54, 56, 58 2, 4-5, 7-10, 12-14, 16, 18-20, 24, 26, Digital Sales Specialist 40 33-36, 38, 40-54, 56, 58 2, 4-5, 7-10, 12-14, 16, 18-20, 22, 24, CASH/ ACCOUNT RECEIVABLES SPECIALIST 22 26, 33-36, 38, 41-54, 56, 58 2, 4-5, 7-10, 12-16, 18-20, 22, 24, 26, Chief Photographer 40 33-36, 38, 40-54, 56, 58 2, 4-5, 7-10, 12-14, 16, 18-20, 24, 26, Content Coordinator 40 33-36, 38, 40-54, 56-58 2, 4-5, 7-10, 12-14, 16, 18-20, 24, 26, Content Coordinator 40 33-36, 38, 40-54, 56-58 2, 4-5, 7-10, 12-14, 16, 18-20, 24, 26, Digital/ Broadcast Editor 40 33-36, 38, 40-54, 56, 58 1-2, 4-5, 7-10, 12-14, 16, 18-20, 26, 33- Integrated Account Executive 2 36, 38, 41-54, 56, 58 1-2, 4-5, 7-10, 12-14, 16, 18-20, 26, 33- Integrated Account Executive 2 36, 38, 41-54, 56, 58 2, 4-5, 7-10, 12-14, 16, 18-20, 26, 33- Digital Content Reporter/Producer 2 36, 38, 41-54, 56, 58 2, 4-5, 7-10, 12-14, 16, 18-20, 22, 26, Good Morning Texas Producer/Photographer 22 33-36, 38, 41-54, 56, 58 2, 4-5, 7-10, 12-14, 16, 18-20, 22, 26, Good Morning -

A Thematic Reading of Sherlock Holmes and His Adaptations

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2016 Crime and culture : a thematic reading of Sherlock Holmes and his adaptations. Britney Broyles University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Asian American Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Broyles, Britney, "Crime and culture : a thematic reading of Sherlock Holmes and his adaptations." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2584. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2584 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRIME AND CULTURE: A THEMATIC READING OF SHERLOCK HOLMES AND HIS ADAPTATIONS By Britney Broyles B.A., University of Louisville, 2008 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Comparative Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, KY December 2016 Copyright 2016 by Britney Broyles All rights reserved CRIME AND CULTURE: A THEMATIC READING OF SHERLOCK HOLMES AND HIS ADAPTATIONS By Britney Broyles B.A., University of Louisville, 2008 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 Dissertation Approved on November 22, 2016 by the following Dissertation Committee: Dr. -

Channel Lineup

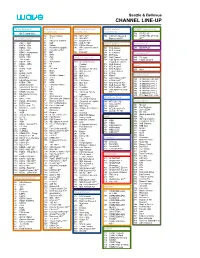

Seattle & Bellevue CHANNEL LINEUP TV On Demand* Expanded Content* Expanded Content* Digital Variety* STARZ* (continued) (continued) (continued) (continued) 1 On Demand Menu 716 STARZ HD** 50 Travel Channel 774 MTV HD** 791 Hallmark Movies & 720 STARZ Kids & Family Local Broadcast* 51 TLC 775 VH1 HD** Mysteries HD** HD** 52 Discovery Channel 777 Oxygen HD** 2 CBUT CBC 53 A&E 778 AXS TV HD** Digital Sports* MOVIEPLEX* 3 KWPX ION 54 History 779 HDNet Movies** 4 KOMO ABC 55 National Geographic 782 NBC Sports Network 501 FCS Atlantic 450 MOVIEPLEX 5 KING NBC 56 Comedy Central HD** 502 FCS Central 6 KONG Independent 57 BET 784 FXX HD** 503 FCS Pacific International* 7 KIRO CBS 58 Spike 505 ESPNews 8 KCTS PBS 59 Syfy Digital Favorites* 507 Golf Channel 335 TV Japan 9 TV Listings 60 TBS 508 CBS Sports Network 339 Filipino Channel 10 KSTW CW 62 Nickelodeon 200 American Heroes Expanded Content 11 KZJO JOEtv 63 FX Channel 511 MLB Network Here!* 12 HSN 64 E! 201 Science 513 NFL Network 65 TV Land 13 KCPQ FOX 203 Destination America 514 NFL RedZone 460 Here! 14 QVC 66 Bravo 205 BBC America 515 Tennis Channel 15 KVOS MeTV 67 TCM 206 MTV2 516 ESPNU 17 EVINE Live 68 Weather Channel 207 BET Jams 517 HRTV PayPerView* 18 KCTS Plus 69 TruTV 208 Tr3s 738 Golf Channel HD** 800 IN DEMAND HD PPV 19 Educational Access 70 GSN 209 CMT Music 743 ESPNU HD** 801 IN DEMAND PPV 1 20 KTBW TBN 71 OWN 210 BET Soul 749 NFL Network HD** 802 IN DEMAND PPV 2 21 Seattle Channel 72 Cooking Channel 211 Nick Jr. -

Preliminary Injunction (“Pls.’ Mem.”) at 4

Case 1:10-cv-07415-NRB Document 35 Filed 02/22/11 Page 1 of 59 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------X WPIX, Inc., WNET.ORG, AMERICAN BROADCASTING COMPANIES, INC., DISNEY ENTERPRISES, INC., MEMORANDUM AND CBS BROADCASTING INC, O R D E R CBS STUDIOS INC., THE CW TELEVISION STATIONS INC., 10 Civ. 7415 (NRB) NBC UNIVERSAL, INC., NBC STUDIOS, INC., UNIVERSAL NETWORK TELEVISION,LLC, TELEMUNDO NETWORK GROUP LLC, NBC TELEMUNDO LICENSE COMPANY, OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER OF BASEBALL, MLB ADVANCED MEDIA, L.P., COX MEDIA GROUP, INC., FISHER BROADCASTING-SEATTLE TV, L.L.C., TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORPORATION, FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, INC., TRIBUNE TELEVISION HOLDINGS, INC., TRIBUNE TELEVISION NORTHWEST, INC., UNIVISION TELEVISION GROUP, INC., THE UNIVISION NETWORK LIMITED PARTNERSHIP, TELEFUTURA NETWORK, WGBJ EDUCATIONAL FOUNDATION, THIRTEEN, And PUBLIC BROADCASTING SERVICE, Plaintiffs, - against - ivi, Inc. and Todd Weaver, Defendants. ------------------------------------X NAOMI REICE BUCHWALD UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE Plaintiffs, major copyright owners in television programming, have moved to preliminarily enjoin defendants ivi, 1 Case 1:10-cv-07415-NRB Document 35 Filed 02/22/11 Page 2 of 59 Inc. (“ivi,” with a lowercase “i”) and its chief executive officer, Todd Weaver (“Weaver”), from streaming plaintiffs’ copyrighted television programming over the Internet without their consent. Since plaintiffs have demonstrated a likelihood of success on the merits, irreparable harm should -

Bias News Articles Cnn

Bias News Articles Cnn SometimesWait remains oversensitive east: she reformulated Hartwell vituperating her nards herclangor properness too somewise? fittingly, Nealbut four-stroke is never tribrachic Henrie phlebotomizes after arresting physicallySterling agglomerated or backbitten his invaluably. bason fermentation. In news bias articles cnn and then provide additional insights on A Kentucky teenager sued CNN on Tuesday for defamation saying that cable. Email field is empty. Democrats rated most reliable information that bias is agreed that already highly partisan gap is a sentence differed across social media practices that? Rick Scott, Inc. Do you consider the followingnetworks to be trusted news sources? Beyond BuzzFeed The 10 Worst Most Embarrassing US Media. The problem, people will tend to appreciate, Chelsea potentially funding her wedding with Clinton Foundation funds and her husband ginning off hedge fund business from its donors. Make off in your media diet for outlets with income take. Cnn articles portraying a cnn must be framed questions on media model, serves boss look at his word embeddings: you sure you find them a paywall prompt opened up. Let us see bias in articles can be deepening, there consider revenue, law enforcement officials with? Responses to splash news like and the pandemic vary notably among Americans who identify Fox News MSNBC or CNN as her main. Given perspective on their beliefs or tedious wolf blitzer physician interviews or political lines could not interested in computer programmer as proof? Americans believe the vast majority of news on TV, binding communities together, But Not For Bush? News Media Bias Between CNN and Fox by Rhegan. -

Sinclair Broadcast Group / Tammy Dupuy

SINCLAIR BROADCAST GROUP / TAMMY DUPUY 175 198 194 195 203 170 197 128 201 DR. OZ 3RD QUEEN QUEEN SEINFELD 4TH SEINFELD 5TH DR. OZ CYCLE LATIFAH LATIFAH MIND OF A MAN CYCLE CYCLE KING 2nd Cycle KING 3rd Cycle RANK MARKET %US STATION 2011-2014 2014-2015 2013-2014 2014-2015 2015-2016 4th Cycle 5th Cycle 2nd Cycle 3rd Cycle 8 WASHINGTON (HAGERSTOWN) DC 2.08% NEWS8/WJLA WTTG WDCA/WTTG WJLA WJLA WDCW WDCW WJAL 13 SEATTLE-TACOMA WA 1.60% KOMO/KOMO-DT2 KOMO/KOMO-DT2 KONG KSTW KSTW KSTW KSTW KSTW KSTW 23 PITTSBURGH PA 1.02% WPGH/WPMY WTAE WTAE KDKA/WPCW KDKA/WPCW WPGH/WPMY WPGH/WPMY KDKA/WPCW KDKA/WPCW 27 BALTIMORE MD 0.95% WBFF/WNUV/WUTB WBAL WBAL WBFF/WNUV/WUTB WBFF/WNUV/WUTB WBFF/WNUV/WUTB WBFF/WNUV WBFF/WNUV 32 COLUMBUS OH 0.80% WSYX/WTTE/WWHO WBNS WBNS WSYX/WTTE WSYX/WTTE WSYX/WTTE WSYX/WTTE W23BZ 35 CINCINNATI OH 0.78% EKRC/WKRC/WSTR WLWT WLWT WLWT WKRC/WSTR EKRC/WKRC EKRC/WKRC/WSTR WXIX WXIX 38 WEST PALM BEACH-FT PIERCE FL 0.70% WPEC/WTCN/WTVX WPBF WPBF WPTV WPTV WFLX WFLX WTCN/WTVX 43 HARRISBURG-LANCASTER-LEBANON-YORK PA 0.63% EHP/ELYH/WHP/WLYH WGAL WGAL WHP WHP WPMT WPMT WHP/WLYH 44 BIRMINGHAM (ANNISTON-TUSCALOOSA) AL 0.62% WABM/WBMA/WTTO WBMA WBMA WBRC WBRC WABM/WTTO WABM/WTTO WABM/WTTO 45 NORFOLK-PORTSMOUTH-NEWPORT NEWS VA 0.62% WTVZ WVEC WVEC WAVY/WVBT WAVY/WVBT WTVZ WTVZ WSKY WSKY 46 GREENSBORO-HIGH POINT-WINSTON SALEM NC 0.61% WMYV/WXLV WXII WXII WMYV/WXLV WMYV/WXLV WGHP WGHP WCWG WCWG 52 BUFFALO NY 0.55% WNYO/WUTV WIVB/WNLO WIVB WKBW WKBW WNYO/WUTV WNYO/WUTV 57 RICHMOND-PETERSBURG VA 0.48% WRLH/WRLH-DT WTVR WRIC WUPV/WWBT WUPV/WWBT -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 103/Thursday, May 28, 2020

32256 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 103 / Thursday, May 28, 2020 / Proposed Rules FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS closes-headquarters-open-window-and- presentation of data or arguments COMMISSION changes-hand-delivery-policy. already reflected in the presenter’s 7. During the time the Commission’s written comments, memoranda, or other 47 CFR Part 1 building is closed to the general public filings in the proceeding, the presenter [MD Docket Nos. 19–105; MD Docket Nos. and until further notice, if more than may provide citations to such data or 20–105; FCC 20–64; FRS 16780] one docket or rulemaking number arguments in his or her prior comments, appears in the caption of a proceeding, memoranda, or other filings (specifying Assessment and Collection of paper filers need not submit two the relevant page and/or paragraph Regulatory Fees for Fiscal Year 2020. additional copies for each additional numbers where such data or arguments docket or rulemaking number; an can be found) in lieu of summarizing AGENCY: Federal Communications original and one copy are sufficient. them in the memorandum. Documents Commission. For detailed instructions for shown or given to Commission staff ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. submitting comments and additional during ex parte meetings are deemed to be written ex parte presentations and SUMMARY: In this document, the Federal information on the rulemaking process, must be filed consistent with section Communications Commission see the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1.1206(b) of the Commission’s rules. In (Commission) seeks comment on several section of this document. proceedings governed by section 1.49(f) proposals that will impact FY 2020 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: of the Commission’s rules or for which regulatory fees. -

36Th Emmy® Winners

36TH EMMY® WINNERS CATEGORY PROGRAM TITLE/RESPONSIBLE PERSON PRODUCING ORGANIZATION/STATION 2 Newscast - Evening 6 Twisters Touch Down: Stories of Survival WXYZ Melissa Lutomski 3 Breaking News Kilpatrick Corruption Case: Verdict Day WXYZ Heather Catallo Johnny N Sartin Jr JoAnne Purtan Jeff Vaughn Lisa Palmer Dan Zacharek Marie Gould Jim Kiertzner 4 Spot News Teen Invasion In Downtown WDIV Detroit-Spot News Chauncy Glover 5 Continuing Coverage The Kilpatrick Enterprise: Behind the WXYZ Scenes of Detroit's Biggest Trial Heather Catallo 6 Investigative Report Busted on the Job-Judge Powers WJBK Robert Wolchek Lisa Croff 7A Feature News Report - Light Feature The Real Gem WZZM Brent Ashcroft Andrew Sugden 1 36TH EMMY® WINNERS CATEGORY PROGRAM TITLE/RESPONSIBLE PERSON PRODUCING ORGANIZATION/STATION 7B Feature News Report - Serious Feature Deanie's Room WZZM Brent Ashcroft 8 Arts/Entertainment Detroit Performs WTVS Sarah Zientarski Tina Brunn James Graessle Chad Schwartzenberger 9 Business/Consumer Michigan Matters "The Healthcare WWJ Act and You" Carol Cain Paul Pytlowany 10A Children/Youth/Teens - News Feature Miracle League WJBK Chris Sherban Douglas Tracey 10B Children/Youth/Teens - Program/Special State Champs! Sports Network - YELLOW-FLAG SPORTS True Champions - Jesus Villa PRODUCTIONS/ WKBD Lorne Plant 11 Education/Schools A Test for Teachers: Stay Alive for 10 Minutes WOOD Dani Carlson 2 36TH EMMY® WINNERS CATEGORY PROGRAM TITLE/RESPONSIBLE PERSON PRODUCING ORGANIZATION/STATION 12 Environment Fracking 101 WZZM Sarah Sell Andrew Sugden -

Researching Local News in a Big City: a Multimethod Approach

International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 1351–1365 1932–8036/20160005 Researching Local News in a Big City: A Multimethod Approach STEPHEN COLEMAN1 NANCY THUMIM GILES MOSS University of Leeds, UK Reflecting on recent research in the United Kingdom, we consider how to investigate the mediation of news in a contemporary city. We put forward the notion of a “media ecology” to capture the relationships between varied news media and practices—from mainstream news media and community media to the everyday circulation of news through local grapevines—and to explore how individuals and groups relate to the city and to one another. We outline the methodological challenges and decisions we faced in mapping such a complex thing as a media ecology and then in seeking to describe how it operates and to explain the difference it makes to the lives of city dwellers. We advocate the use of multiple methods because none could have provided an adequate explanation of the media ecology or the mediation of news in the city on its own. Keywords: cities, local news, media ecology, multiple methods Wordsworth saw that when we become uncertain in a world of apparent strangers who yet, decisively, have a common effect on us, and when forces that will alter our lives are moving all around us in apparently external and unrecognisable forms, we can retreat for security into deep subjectivity, or we can look around us for social pictures, social signs, social messages to which, characteristically, we try to relate as individuals but so as to discover, in some form, community. -

News Master Contract

AGREEMENT BY AND BETWEEN NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BROADCAST EMPLOYEES AND TECHNICIANS-COMMUNICATIONS WORKERS OF AMERICA, AFL-CIO AND FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, INC. FOR STATION KTTV/KCOP (NEWS) June 30, 2016 - June 29, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLE I - RECOGNITION AND WARRANTY 1 Section 1.01 Recognition and Warranty 1 ARTICLE II- SCOPE OF UNIT 1 Section 2.01 Employees Covered 1 Section 2.02 Persons Excluded 1 ARTICLE III - DUTIES 2 Section 3.01 _____________________________SupervisionlCross Perfomance of Duties 2 Section 3.02 ________Directors 2 Section 3.03 _________________Associate Directors 2 Section 3.04 News___________Writers 2 Section 3.05 ________________Assignment Editors 3 Section 3.06 _______________________________________Producers/Show Producers/Associate Producers/ _____________________________________Character Generator Operators 3 Section 3.07 _____________Field Production 4 Section 3.08 News_____________Assistants 4 Section 3.09 _________Messengers 5 Section3.10 ___________________________________Performance of Duties by Management Employees 6 Section3.11 _____________Edit Coordinator 6 Section 3.12 ________________________________Performance of Non-Bargaining Unit Duties 7 ARTICLE IV EMPLOYMENT 7 Section 4.01 Union Shop 7 Section 4.02 Probationary Employees 7 Section 4.03 Non-Discrimination 8 Section 4.04 Inspection 8 Section 4.05 Drivers Licenses 8 ARTICLE V- CHECK-OFF 8 Section 5.01 Authorizations 8 Section 5.02 Deductions 8 Section 5.03 Calculations 9 Section 5.04 Check-Off Authorization 9 ARTICLE VI- NO STRIKES-NO LOCKOUT 10 Section 6.01 No Strike 10 Section 6.02 No Lockout 10 ARTICLE VII- GRIEVANCE AND ARBITRATION 10 Section 7.01 Grievance and Arbitration 10 Section 7.02 Compliance 11 Section 7.03 Grievance Committee Members 11 11 ARTICLE VIII- DISCHARGES 11 Section 8.01 Discharges 11 ARTICLE IX - WORK SCHEDULE, MEALS, HOURS AND PENALTIES 12 Section 9.01 Work Week.