Graduate Viola Recital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symphony in B Flat Major 11 Min Wilhelm Friedemann Bach

Andrew Manze, conductor Johann Georg Pisendel: Symphony in B flat major 11 min I Allegro di molto II Andantino III Tempo di menuet Wilhelm Friedemann Bach: Adagio and Fugue in D minor Fk 65 10 min I Adagio II Fugue Jan Dismas Zelenka Hipocondrie Overture in A major 9 min Antonio Vivaldi: Concerto for the Dresden Orchestra in 12 min G minor RV 576 I Allegro II Larghetto III Allegro INTERVAL 15 min Antonio Lotti: Crucifixus (arr. Andrew Manze) 4 min Dmitri Shostakovich: Chamber Symphony in C minor, 23 min (arr. Rudolf Barshai) Op. 110bis I Largo II Allegro molto III Scherzo (Allegretto) IV Largo V Largo Interval at about 7.55 pm. The concert ends at about 20.45 pm. Broadcast live on YLE Radio 1 and the Internet (www.yle.fi) 1 Music from Dresden Sometimes known as “the Florence on the Elbe”, ern Germany. By contrast, the Elector was more Dresden grew in the first half of the 18th century in favour of the French style while his son, Crown into a city of Baroque palaces, art and music with a Prince Friedrich August II, preferred the Italian. thriving court culture. It was to the German-speak- On the death of his father, the Crown Prince be- ing regions of Europe what Florence had been to came Elector of Saxony and King August III of Po- Renaissance Italy. land in 1733. The credit for Dresden’s golden era goes to Au- Despite his debts, August III continued the gran- gust II the Strong (1670–1733), who in 1694 be- diose court culture established by his father. -

1962 FMAC SS.Pdf

WIND DRUM The music of WIND DRUM is composed on a six-tone scale. In South India, this scale is called "hamsanandi," in North India, "marava." In North India, this scale would be played before sunset. The notes are C, D flat, E, F sharp, A, and B. PREFACE The mountain island of Hawaii becomes a symbol of an island universe in an endless ocean of nothingness, of space, of sleep. This is the night of Brahma. Time swings back and forth, time, the giant pendulum of the universe. As time swings forward all things waken out of endless slumber, all things grow, dance, and sing. Motion brings storm, whirlwind, tornado, devastation, destruction, and annihilation. All things fall into death. But with total despair comes sudden surprise. The super natural commands with infinite majesty. All storms, all motions cease. Only the celestial sounds of the Azura Heavens are heard. Time swings back, death becomes life, resurrection. All things are reborn, grow, dance, and sing. But the spirit of ocean slumber approaches and all things fall back again into sleep and emptiness, the state of endless nothingness symbolized by ocean. The night of Brahma returns. LIBRETTO I VI Stone, water, singing grass, Flute of Azura, Singing tree, singing mountain, Fill heaven with celestial sound! Praise ever-compassionate One. Death, become life! II VII Island of mist, Sun, melt, dissolve Awake from ocean Black-haired mountain storm, Of endless slumber. Life drum sing, III Stone drum ring! Snow mountain, VIII Dance on green hills. Trees singing of branches IV Sway winds, Three hills, Forest dance on hills, Dance on forest, Hills, green, dance on Winds, sway branches Mountain snow. -

Flint Orchestra

Flint SymphonyOrchestra A Program of the Flint Institute of Music ENRIQUE DIEMECKE, MUSIC DIRECTOR & CONDUCTOR MAY 8, 2021 FIM SEASON SPONSOR Whiting Foundation CONCERT SPONSORS Mr. Edward Davison, Attorney at Law & Dr. Cathy O. Blight, Dr. Brenda Fortunate & C. Edward White, Mrs. Linda LeMieux, Drs. Bobby & Nita Mukkamala, Dr. Mark & Genie Plucer Flint Symphony Orchestra THEFSO.ORG 2020 – 21 Season SEASON AT A GLANCE Flint Symphony Orchestra Flint School of Performing Arts Flint Repertory Theatre STRAVINSKY & PROKOFIEV FAMILY DAY SAT, FEB 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Cathy Prevett, narrator SAINT-SAËNS & BRAHMS SAT, MAR 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Noelle Naito, violin 2020 William C. Byrd Winner WELCOME TO THE 2020 – 21 SEASON WITH YOUR FLINT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA! BEETHOVEN & DVOŘÁK SAT, APR 10, 2021 @ 7:30PM he Flint Symphony Orchestra (FSO) is one of Joonghun Cho, piano the finest orchestras of its size in the nation. BRUCH & TCHAIKOVSKY TIts rich 103-year history as a cultural icon SAT, MAY 8, 2021 @ 7:30PM in the community is testament to the dedication Julian Rhee, violin of world-class performance from the musicians AN EVENING WITH and Flint and Genesee County audiences alike. DAMIEN ESCOBAR The FSO has been performing under the baton SAT, JUNE 19, 2021 @ 7:30PM of Maestro Enrique Diemecke for over 30 years Damien Escobar, violin now – one of the longest tenures for a Music Director in the country. Under the Maestro’s unwavering musical integrity and commitment to the community, the FSO has connected with audiences throughout southeast Michigan, delivering outstanding artistry and excellence. All dates are subject to change. -

ALAN HOVHANESS: Meditation on Orpheus the Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra William Strickland, Conducting

ALAN HOVHANESS: Meditation on Orpheus The Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra William Strickland, conducting ALAN HOVHANESS is one of those composers whose music seems to prove the inexhaustability of the ancient modes and of the seven tones of the diatonic scale. He has made for himself one of the most individual styles to be found in the work of any American composer, recognizable immediately for its exotic flavor, its masterly simplicity, and its constant air of discovering unexpected treasures at each turn of the road. Meditation on Orpheus, scored for full symphony orchestra, is typical of Hovhaness’ work in the delicate construction of its sonorities. A single, pianissimo tam-tam note, a tone from a solo horn, an evanescent pizzicato murmur from the violins (senza misura)—these ethereal elements tinge the sound of the middle and lower strings at the work’s beginning and evoke an ambience of mysterious dignity and sensuousness which continues and grows throughout the Meditation. At intervals, a strange rushing sound grows to a crescendo and subsides, interrupting the flow of smooth melody for a moment, and then allowing it to resume, generally with a subtle change of scene. The senza misura pizzicato which is heard at the opening would seem to be the germ from which this unusual passage has grown, for the “rushing” sound—dynamically intensified at each appearance—is produced by the combination of fast, metrically unmeasured figurations, usually played by the strings. The composer indicates not that these passages are to be played in 2/4, 3/4, etc. but that they are to last “about 20 seconds, ad lib.” The notes are to be “rapid but not together.” They produce a fascinating effect, and somehow give the impression that other worldly significances are hidden in the juxtaposition of flow and mystical interruption. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Euphonium Repertoire List Title Composer Arranger Grade Air Varie

Euphonium Repertoire List Title Composer Arranger Grade Air Varie Pryor Smith 1 Andante and Rondo Capuzzi Catelinet 1 Andante et Allegro Ropartz Shapiro 1 Andante et Allegro Barat 1 Arpeggione Sonata Schubert Werden 1 Beautiful Colorado DeLuca 1 Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms Mantia Werden 1 Blue Bells of Scotland Pryor 1 Bride of the Waves Clarke 1 Buffo Concertante Jaffe Centone 1 Carnival of Venice Clark Brandenburg 1 Concert Fantasy Cords Laube 1 Concert Piece Nux 1 Concertino No. 1 in Bb Major Op. 7 Klengel 1 Concertino Op. 4 David 1 Concerto Capuzzi Baines 1 Concerto in a minor Vivaldi Ostrander 1 Concerto in Bb K.191 Mozart Ostrander 1 Eidolons for Euphonium and Piano Latham 1 Fantasia Jacob 1 Fantasia Di Concerto Boccalari 1 Fantasie Concertante Casterede 1 Fantasy Sparke 1 Five Pieces in Folk Style Schumann Droste 1 From the Shores of the Mighty Pacific Clarke 1 Grand Concerto Grafe Laude 1 Heroic Episode Troje Miller 1 Introduction and Dance Barat Smith 1 Largo and Allegro Marcello Merriman 1 Lyric Suite White 1 Mirror Lake Montgomery 1 Montage Uber 1 Morceau de Concert Saint-Saens Nelson 1 Euphonium Repertoire List Morceau Symphonique Op. 88 Guilmant 1 Napoli Bellstedt Simon 1 Nocturne and Rondolette Shepherd 1 Partita Ross 1 Piece en fa mineur Morel 1 Rhapsody Curnow 1 Rondo Capriccioso Spears 1 Sinfonia Pergolesi Sauer 1 Six Sonatas Volume I Galliard Brown 1 Six Sonatas Volume II Galliard Brown 1 Sonata Whear 1 Sonata Clinard 1 Sonata Besozzi 1 Sonata White 1 Sonata Euphonica Hartley 1 Sonata in a minor Marcello -

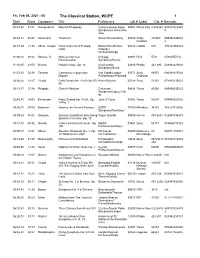

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Fri, Feb 05, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 31:51 Humperdinck Moorish Rhapsody Czecho-Slovak Radio 00509 Marco Polo 8.223369 489103023363 Symphony/Fischer-Die 0 skau 00:34:2102:08 Schumann Traumerei Alexis Weissenberg 07843 Virgin 234865 509992348652 Classics 2 00:37:2921:34 White, Joseph Violin Concerto in F sharp Barton Pine/Encore 04328 Cedille 035 735131903523 minor Chamber Orchestra/Hege 01:00:23 08:32 Strauss, R. Waltzes from Der Chicago 00458 RCA 5721 07863557212 Rosenkavalier Symphony/Reiner 01:10:0542:05 Berlioz Harold in Italy, Op. 16 Imai/London 02693 Philips 442 290 028944229028 Symphony/Davis 01:53:20 05:30 Thomas Connais-tu le pays from Von Stade/London 05873 Sony 89370 696998937024 Mignon Philharmonic/Pritchard Classical 02:00:2013:27 Vivaldi Cello Sonata No. 4 in B flat, RV Anner Bylsma 05188 Sony 51350 074645135021 45 02:15:17 27:48 Respighi Church Windows Cincinnati 08438 Telarc 80356 089408035623 Symphony/Lopez-Cob os 02:44:3514:08 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 9 in E, Op. John O'Conor 05592 Telarc 80293 089408029325 14 No. 1 03:00:1307:50 Balakirev Islamey, an Oriental Fantasy USSR 05750 Melodiya 34165 743213416526 Symphony/Svetlanov 03:09:0308:02 Debussy 3rd mvt (Andantino) from String Ysaye Quartet 09850 Decca 478 3691 028947836919 Quartet in G minor, Op. 10 03:18:1540:32 Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. Ma/NY 03691 Sony 67173 074646717325 104 Philharmonic/Masur 04:00:1712:51 Alfven Swedish Rhapsody No. -

Max Bruch Symphonies 1–3 Overtures Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino

Max Bruch Symphonies 1–3 Overtures Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 1 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Max Bruch, 1870 cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 2 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Max Bruch (1838–1920) Complete Symphonies CD 1 Symphony No. 1 op. 28 in E flat major 38'04 1 Allegro maestoso 10'32 2 Intermezzo. Andante con moto 7'13 3 Scherzo. Presto 5'00 4 Quasi Fantasia. Grave 7'30 5 Finale. Allegro guerriero 7'49 Symphony No. 2 op. 36 in F minor 39'22 6 Allegro passionato, ma un poco maestoso 15'02 7 Adagio ma non troppo 13'32 8 Allegro molto tranquillo 10'57 T.T.: 77'30 cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 3 13.03.2020 10:56:27 CD 2 1 Prelude from Hermione op. 40 8'54 (Concert ending by Wolfgang Jacob) 2 Funeral march from Hermione op. 40 6'15 3 Entr’acte from Hermione op. 40 2'35 4 Overture from Loreley op. 16 4'53 5 Prelude from Odysseus op. 41 9'54 Symphony No. 3 op. 51 in E major 38'30 6 Andante sostenuto 13'04 7 Adagio ma non troppo 12'08 8 Scherzo 6'43 9 Finale 6'35 T.T.: 71'34 Bamberger Symphoniker Robert Trevino, Conductor cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 4 13.03.2020 10:56:27 Bamberger Symphoniker (© Andreas Herzau) cpo 555 252–2 Booklet.indd 5 13.03.2020 10:56:28 Auf Eselsbrücken nach Damaskus – oder: darüber, daß wir es bei dieser Krone der Schöpfung Der steinige Weg zu Bruch dem Symphoniker mit einem Kompositum zu tun haben, das sich als Geist mit mehr oder minder vorhandenem Verstand in einem In der dichtung – wie in aller kunst-betätigung – ist jeder Körper darstellt (die Bezeichnungen der Ingredienzien der noch von der sucht ergriffen ist etwas ›sagen‹ etwas ›wir- mögen wechseln, die Tatsache bleibt). -

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Being Mendelssohn the seventh season july 17–august 8, 2009 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 5 Welcome from the Executive Director 7 Being Mendelssohn: Program Information 8 Essay: “Mendelssohn and Us” by R. Larry Todd 10 Encounters I–IV 12 Concert Programs I–V 29 Mendelssohn String Quartet Cycle I–III 35 Carte Blanche Concerts I–III 46 Chamber Music Institute 48 Prelude Performances 54 Koret Young Performers Concerts 57 Open House 58 Café Conversations 59 Master Classes 60 Visual Arts and the Festival 61 Artist and Faculty Biographies 74 Glossary 76 Join Music@Menlo 80 Acknowledgments 81 Ticket and Performance Information 83 Music@Menlo LIVE 84 Festival Calendar Cover artwork: untitled, 2009, oil on card stock, 40 x 40 cm by Theo Noll. Inside (p. 60): paintings by Theo Noll. Images on pp. 1, 7, 9 (Mendelssohn portrait), 10 (Mendelssohn portrait), 12, 16, 19, 23, and 26 courtesy of Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY. Images on pp. 10–11 (landscape) courtesy of Lebrecht Music and Arts; (insects, Mendelssohn on deathbed) courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library. Photographs on pp. 30–31, Pacifica Quartet, courtesy of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Theo Noll (p. 60): Simone Geissler. Bruce Adolphe (p. 61), Orli Shaham (p. 66), Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 83): Christian Steiner. William Bennett (p. 62): Ralph Granich. Hasse Borup (p. 62): Mary Noble Ours. -

The Voice of the Viola in Times of Oppression Ásdís

The Voice of the Viola in Times of Oppression Ásdís Valdimarsdóttir viola Marcel Worms piano The Voice of the Viola Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847) in Times of Oppression Sonata for viola and piano (1824) Ásdís Valdimarsdóttir 1 6’45 Adagio - Allegro viola 2 6’23 Menuetto (Allegro molto) and Trio (Più lento) Marcel Worms 3 12’59 Andante con variazioni piano Hans Gál (1890-1987) Sonata op.101 for viola and piano (1941) 4 6’15 Adagio 5 5’31 Quasi menuetto, tranquillo 6 6’58 Allegro risoluto e vivace Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) 7 1’39 Impromptu for viola and piano (1931) Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) Sonata for viola and piano (1939) 8 7’18 Breit, mit Kraft 9 5’02 Sehr lebhaft 10 4’05 Phantasie: sehr langsam,frei 11 7’35 Finale: leicht bewegt total time: 70’32 The Voice of the Viola in Times of Oppression 2 THE VIOLA is surely not the most assertive instrument Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809-1847) Hans Gál (1890-1987) among the string family. It reaches neither the extreme Sonata for Viola and Piano (1824) Sonata op.101 for viola and piano (1941) height of the violin nor the rumbling depth and the Mendelssohn was only fifteen years old when he wrote Hans Gál was born in the vicinity of Vienna. Until his death, strength of the cello and contrabass. Its role is more his sonata for viola and piano. An opus number was late in the twentieth century and outside Central Europe, integrating than leading or polarising; and in brilliance, not assigned to the work by the young composer, and he let that Viennese origin resonate in his music. -

Verdehr Trio Verdehr Trio

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 2-22-1991 Concert: Verdehr Trio Verdehr Trio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Verdehr Trio, "Concert: Verdehr Trio" (1991). All Concert & Recital Programs. 5582. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/5582 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College ITHACA School of Music ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 1990-91 VERDEHR TRIO Walter Verdehr, violin Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr, clarinet Gary Kirkpatrick, piano CREATURES OF PROMETHEUS, op. 43 Ludwig van Beethoven No. 14 Andante and Allegretto (1770-1827) EIGHT PIECES FOR CLARINET, VIOLA AND PIANO, op. 83 Max Bruch (1838-1920) transcribed by Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr VI. Nachtgesang: Andante con moto (Nocturn) IV. Allegro agitato A TRIO SETTING (19<JO) Gwither SchQller (b. 1925) Fast and Explosive Slow and Dreamy Allegretto; Scherzando e Leggiero IN1ERMISSION SONATA A TRE (1982) KarelHusa (b.1921) Con intensita Con sensitivita Con velocita SLAVONIC DANCES Antonin Dvofak (1841-1904) Tempo di Menuetto, op. 46, no. 2 Allegretto grazioso, op. 72, no. 2 Presto, op. 46, no. 8 Walter Ford Hall Auditorium Friday, February 22, 1991 8:15 p.m. PROGRAM NOTES Ludwig van Beethoven. Creatures of Prometheus, op. 43 The Andante and Allegretto, op. 43, no. 14 by Beethoven is taken from the ballet Creatures of Prometheus, op. 43. Written in 1800-1801, it was Beethoven's introduction to the Viennese stage and the first performance was given in the Burgtheater in Vienna on March 28, 1801. -

Thesis and the Work Presented in It Is Entirely My Own

! ! ! ! ! Christopher Tarrant! Royal Holloway, University! of London! ! ! Schubert, Sonata Theory, Psychoanalysis: ! Traversing the Fantasy in Schubert’s Sonata Forms! ! ! Submission for the Degree of Ph.D! March! 2015! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "1 ! Declaration of! Authorship ! ! I, Christopher Tarrant, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stat- !ed. ! ! ! Signed: ______________________ ! Date: March 3, 2015# "2 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! For Mum and Dad "3 Acknowledgements! ! This project grew out of a fascination with Schubert’s music and the varied ways of analysing it that I developed as an undergraduate at Lady Margaret Hall, University of Oxford. It was there that two Schubert scholars, Suzannah Clark and Susan Wollen- berg, gave me my first taste of the beauties, the peculiarities, and the challenges that Schubert’s music can offer. Having realised by the end of the course that there was a depth of study that this music repays, and that I had only made the most modest of scratches into its surface, I decided that the only way to satisfy the curiosity they had aroused in me was to continue studying the subject as a postgraduate.! ! It was at Royal Holloway that I began working with my supervisor, Paul Harper-Scott, to whom I owe a great deal. Under his supervision I was not only introduced to Hep- okoskian analysis and Sonata Theory, which forms the basis of this thesis, but also a bewildering array of literary theory that sparked my imagination in ways that I could never have foreseen.