Art Rooney, Jr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Objectivity, Interdisciplinary Methodology, and Shared Authority

ABSTRACT HISTORY TATE. RACHANICE CANDY PATRICE B.A. EMORY UNIVERSITY, 1987 M.P.A. GEORGIA STATE UNIVERSITY, 1990 M.A. UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN- MILWAUKEE, 1995 “OUR ART ITSELF WAS OUR ACTIVISM”: ATLANTA’S NEIGHBORHOOD ARTS CENTER, 1975-1990 Committee Chair: Richard Allen Morton. Ph.D. Dissertation dated May 2012 This cultural history study examined Atlanta’s Neighborhood Arts Center (NAC), which existed from 1975 to 1990, as an example of black cultural politics in the South. As a Black Arts Movement (BAM) institution, this regional expression has been missing from academic discussions of the period. The study investigated the multidisciplinary programming that was created to fulfill its motto of “Art for People’s Sake.” The five themes developed from the program research included: 1) the NAC represented the juxtaposition between the individual and the community, local and national; 2) the NAC reached out and extended the arts to the masses, rather than just focusing on the black middle class and white supporters; 3) the NAC was distinctive in space and location; 4) the NAC seemed to provide more opportunities for women artists than traditional BAM organizations; and 5) the NAC had a specific mission to elevate the social and political consciousness of black people. In addition to placing the Neighborhood Arts Center among the regional branches of the BAM family tree, using the programmatic findings, this research analyzed three themes found to be present in the black cultural politics of Atlanta which made for the center’s unique grassroots contributions to the movement. The themes centered on a history of politics, racial issues, and class dynamics. -

CHUCK NOLL HALL of FAME “GAME for LIFE” AWARD to HONOR YOUTH FOOTBALL PROGRAMS Award Created by Merril Hoge Celebrates Pro Football Hall of Fame Coach Chuck Noll

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 8/2/17 Contact: Pete Fierle, Pro Football Hall of Fame, (330) 588-3622 Melinda Whitemarsh, USA Football, (317) 489-4431 CHUCK NOLL HALL OF FAME “GAME FOR LIFE” AWARD TO HONOR YOUTH FOOTBALL PROGRAMS Award Created by Merril Hoge Celebrates Pro Football Hall of Fame Coach Chuck Noll CANTON, OHIO – The Pro Football Hall of Fame, in partnership with USA Football, is teaming with DICK’S Sporting Goods, Riddell and adidas to introduce the Chuck Noll Hall of Fame “Game for Life” Award. The honor will be presented to youth football programs in every state that exemplify the values of football: commitment, integrity, courage, respect, and excellence. As he taught America’s favorite sport, legendary Hall of Fame coach CHUCK NOLL personified these timeless values, which are foundational to the game and championed by Pro Football Hall of Fame and USA Football. Leagues that earn the Chuck Noll Hall of Fame “Game for Life” Award will be recognized for their commitment to coaching education; best practices in player safety; teaching lessons about how to win rather than emphasizing winning; and nurturing a culture that celebrates preparation, discipline, accountability and respect through the fun and fitness of football and how it applies to success beyond the field. These winning attributes parallel the philosophies for which Coach Noll stood and are supported for the good of young athletes by the Pro Football Hall of Fame, USA Football, DICK’S Sporting Goods and The DICK’S Sporting Goods Foundation’s Sports Matter program, Riddell and adidas. Each of the 50 recognized youth leagues will receive: • $500 equipment grant from Riddell and USA Football; • $500 gift card from DICK’S Sporting Goods • $500 gift card from adidas. -

1956 Topps Football Checklist

1956 Topps Football Checklist 1 John Carson SP 2 Gordon Soltau 3 Frank Varrichione 4 Eddie Bell 5 Alex Webster RC 6 Norm Van Brocklin 7 Packers Team 8 Lou Creekmur 9 Lou Groza 10 Tom Bienemann SP 11 George Blanda 12 Alan Ameche 13 Vic Janowicz SP 14 Dick Moegle 15 Fran Rogel 16 Harold Giancanelli 17 Emlen Tunnell 18 Tank Younger 19 Bill Howton 20 Jack Christiansen 21 Pete Brewster 22 Cardinals Team SP 23 Ed Brown 24 Joe Campanella 25 Leon Heath SP 26 49ers Team 27 Dick Flanagan 28 Chuck Bednarik 29 Kyle Rote 30 Les Richter 31 Howard Ferguson 32 Dorne Dibble 33 Ken Konz 34 Dave Mann SP 35 Rick Casares 36 Art Donovan 37 Chuck Drazenovich SP 38 Joe Arenas 39 Lynn Chandnois 40 Eagles Team 41 Roosevelt Brown RC 42 Tom Fears 43 Gary Knafelc Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Joe Schmidt RC 45 Browns Team 46 Len Teeuws RC, SP 47 Bill George RC 48 Colts Team 49 Eddie LeBaron SP 50 Hugh McElhenny 51 Ted Marchibroda 52 Adrian Burk 53 Frank Gifford 54 Charles Toogood 55 Tobin Rote 56 Bill Stits 57 Don Colo 58 Ollie Matson SP 59 Harlon Hill 60 Lenny Moore RC 61 Redskins Team SP 62 Billy Wilson 63 Steelers Team 64 Bob Pellegrini 65 Ken MacAfee 66 Will Sherman 67 Roger Zatkoff 68 Dave Middleton 69 Ray Renfro 70 Don Stonesifer SP 71 Stan Jones RC 72 Jim Mutscheller 73 Volney Peters SP 74 Leo Nomellini 75 Ray Mathews 76 Dick Bielski 77 Charley Conerly 78 Elroy Hirsch 79 Bill Forester RC 80 Jim Doran 81 Fred Morrison 82 Jack Simmons SP 83 Bill McColl 84 Bert Rechichar 85 Joe Scudero SP 86 Y.A. -

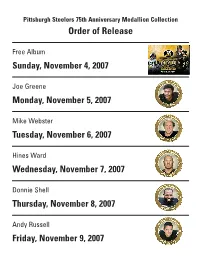

PSL Medallion Release Order.V1

Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Free Album Sunday, November 4, 2007 Joe Greene Monday, November 5, 2007 Mike Webster Tuesday, November 6, 2007 Hines Ward Wednesday, November 7, 2007 Donnie Shell Thursday, November 8, 2007 Andy Russell Friday, November 9, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Carnell Lake Saturday, November 10, 2007 Terry Bradshaw Sunday, November 11, 2007 Casey Hampton Monday, November 12, 2007 Rocky Bleier Tuesday, November 13, 2007 Greg Lloyd Wednesday, November 14, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Elbie Nickel Thursday, November 15, 2007 Rod Woodson Friday, November 16, 2007 Larry Brown Saturday, November 17, 2007 Lynn Swann Sunday, November 18, 2007 Dermontti Dawson Monday, November 19, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Bobby Walden Tuesday, November 20, 2007 Joey Porter Wednesday, November 21, 2007 Jack Ham Thursday, November 22, 2007 Tunch Ilkin Friday, November 23, 2007 Gary Anderson Saturday, November 24, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Franco Harris Sunday, November 25, 2007 Commemorative Medallion Monday, November 26, 2007 L.C. Greenwood Tuesday, November 27, 2007 Jack Butler Wednesday, November 28, 2007 Jon Kolb Thursday, November 29, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Dwight White Friday, November 30, 2007 Ernie Stautner Saturday, December 1, 2007 Jerome Bettis Sunday, December 2, 2007 Alan Faneca Monday, December 3, 2007 Bennie Cunningham Tuesday, December 4, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Troy Polamalu Wednesday, December 5, 2007 Mel Blount Thursday, December 6, 2007 John Stallworth Friday, December 7, 2007 Bonus Coupon Saturday, December 8, 2007 BONUS COUPON for any previously released medallion Here is a chance to collect any medallion you may have missed so far. -

Hall of Fame Admission Promotion Offered to Steelers and Browns Fans

Honor the Heroes of the Game, Preserve its History, Promote its Values & Celebrate Excellence EVERYWHERE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE @ProFootballHOF 11/17/2016 Contact: Pete Fierle, Chief of Staff & Vice President of Communications [email protected]; 330-588-3622 HALL OF FAME ADMISSION PROMOTION OFFERED TO STEELERS AND BROWNS FANS FANS VISITING REGION FOR THE WEEK 11 MATCH-UP TO RECEIVE SPECIAL ADMISSION DISCOUNT FOR WEARING TEAM GEAR CANTON, OHIO – The Pro Football Hall of Fame is inviting Pittsburgh Steelers and Cleveland Browns fans in northeast Ohio this weekend to experience “The Most Inspiring Place on Earth!” The Steelers take on the Browns this Sunday (Nov. 20) at 1:00 p.m. at FirstEnergy Stadium. The Pro Football Hall of Fame is just under an hour’s drive south of Cleveland. Any Steelers or Browns fan dressed in their team’s gear who mentions the promotion at the Hall’s box office will receive a $5 discount on any regular price museum admission. The promotion runs from Friday, Nov. 18 through Monday, Nov. 21. The Hall of Fame is open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily. Information about planning a visit to the Hall of Fame can be found at: www.ProFootballHOF.com/visit/. STEELERS IN CANTON The Steelers have 21 longtime members enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame – the third most by any current NFL franchise after the Chicago Bears (27) and the Green Bay Packers (24). Longtime Pittsburgh players include: JEROME BETTIS (Running Back, 1996-2005, Class of 2015), MEL BLOUNT (Cornerback, 1970-1983, Class of 1989), TERRY BRADSHAW -

Granby Mother Kills Her 2 Small Children

r"T ' ' j •'.v> ■ I SATUBDAY, DECEMBER 24, 1960 V‘‘‘ iOanrtifBter E w ttins $?raUt Ifii'J •• t Not (me of the men MW anything funny In the process. No Herald Social Worker About To>m Heard Along Main Street! Just like a woman 7 Some of the men fall in the know-how Pepart- OnMdhday Sought by Town WATBS wlU meet And on Some o) Manehe$ter*§ Side SlreeU,Too ment, too, when it. comes to freeing l^iesdey evening nt the Italian mechanical horses from Ice traps. The town is accepting appUca- The Manchester Evening tiona through Wednesday to fill Amertean ' Chib on Sldrltlge St. <^been a. luncheon guest at the inn. 1 0 :' Welgbtog In win be from 7 to 8 What Are You Gonna Do? It ' So Reverse It a social work^ post with sn an One Herald aubacriber is very Lt. Leander, who is stationed at Herald will-not publish Mon 'Words of advice wer^ voiced nual salary range of 84,004 to YOL. LXXX, NO. 7S (SIXTEEN PAGES) MANCHESTER, CONN„ TUESDAY. DECEMBER 27, 1960 (ChuwUtsg AgvsrttalBg m Fag» 14) PRICE PIVB V-*A red-faced becauee her 10-year-oM the U.S. Navy atatipn .gt Orange, irom one local youngster to an day, the day after Christmas, 14,914 and an allowance for use son got carried away with the Tex., had spent the afterhiibh vla- other as they walked along the Merty Christmas to all. of the worker's own car. Handd S. Crozler will show Christmas spirit. Iting a state park, San Jacinto street in the ijear zero weather. -

1.) What Was the Original Name of the Pittsburgh Steelers? B. the Pirates

1.) What was the original name of the Pittsburgh Steelers? B. The Pirates The Pittsburgh football franchise was founded by Art Rooney on July 7, 1933. When he chose the name for his team, he followed the customary practice around the National Football League of naming the football team the same as the baseball team if there was already a baseball team established in the city. So the professional football team was originally called the Pittsburgh Pirates. 2.) How many Pittsburgh Steelers have had their picture on a Wheaties Box? C. 13 Since Wheaties boxes have started featuring professional athletes and other famous people, 13 Steelers have had their pictures on the box. These players are Kevin Greene, Greg Lloyd, Neil O'Donnell, Yancey Thigpen, Bam Morris, Franco Harris, Joe Greene, Terry Bradshaw, Barry Foster, Merril Hoge, Carnell Lake, Bobby Layne, and Rod Woodson. 3.) How did sportscaster Curt Gowdy refer to the Immaculate Reception, which happened two days before Christmas? Watch video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GMuUBZ_DAeM A. The Miracle of All Miracles “You talk about Christmas miracles. Here's the miracle of all miracles. Watch this one now. Bradshaw is lucky to even get rid of the ball! He shoots it out. Jack Tatum deflects it right into the hands of Harris. And he sets off. And the big 230-pound rookie slipped away from Warren and scored.” —Sportscaster Curt Gowdy, describing an instant replay of the play on NBC 4.) URA Acting Executive Director Robert Rubinstein holds what football record at Churchill Area High School? B. -

100 Years of African American History: a Fiber Art Retrospective by Tina Williams Brewer

100 Years of african american HistorY: a fiber art retrospective by tina Williams Brewer 100 Years of african american HistorY: a fiber art retrospective by tina Williams Brewer This publication was made possible through a generous contribution to Pittsburgh Filmmakers/Pittsburgh Center for the Arts from Alcoa Foundation. It happened... the Courier was there. Rod Doss, Editor and Publisher, New Pittsburgh Courier he Pittsburgh Courier has recorded news affecting The information reported in the Courier had a pro- African-Americans since 1910. My staff and I are found impact on Black politics, world events, civil Thonored to be the “keepers” of what is an incred- rights, sports, entertainment, business and journal- ible and extensive record – both in print and in photo- ism. We are privileged to associate with those giants graphs – of a people’s culture that has had profound who recorded the history of a people’s unwavering impact on American history. march to overcome the many obstacles that withheld The Courier was first published 100 years ago and even- their dignity as a mighty race of people. As the Black tually became the most widely circulated Black news- intellectual W.E.B. DuBois said, “The twentieth century paper in the country with 21 regional editions and an challenge to resolve the issue of color is the greatest international edition. At its height, more than 450,000 challenge America will have to overcome.” His words people received the Courier each week and were were truly prophetic. given the opportunity to read an unvarnished version The series of 10 quilts created by Tina Williams Brewer of cultural and historical events that told the story in this exhibition attempt to provide a broad-based of the Black experience in America. -

Ball State Vs Clemson (9/5/1992)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1992 Ball State vs Clemson (9/5/1992) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "Ball State vs Clemson (9/5/1992)" (1992). Football Programs. 217. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/217 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. $3.00 Clemson fi% Ball State Memorial Stadium September 5, 1992 TEMAFA - Equipmentforfiber reclamation. DORNIER - TJie Universal weaving machine. Air jet and VOUK - Draw Frames, Combers, tappers, Automatic rigid rapier. Transport systems. SOHLER - Traveling blowing and vacuuming systems. DREF 2 AND DREF 3 - Friction spinning system. GENKINGER - Material handling systems. FEHRER - NL 3000: Needling capabilities up to 3000 - inspection systems. strokes per minute. ALEXANDER Offloom take-ups and HACOBA - Complete line of warping and beaming LEMAIRE - Warp transfer andfabric transfer printing. machinery. FONGS - Equipmentfor piece and package dyeing. KNOTEX- Will tie all yarns. -

Stealers OFFENSE 48 Rawser, John CB 51 Ball, Lorry LB LE68L.C

MIAMI DOLPHINSvs.PITTSBURGHSTEELIRS DOLPHINS DECEMBER 3,1973 — ORANGE BOWL, MIAMI STEELERS NO. NAME POS. NO. NAME PUS. 1 Yapremian, Gwo K 5 Honesty, terry OS 10Strock, Den OB OFFENSE DEFENSE 10 Qerelo, Roy K 12Grin., Bob OR 12 Sradshaw, Tqrry OS 13Scott, Jake $ WR 42 Paul Warfield 82 Bo Rather 34 Ron Sellers LE83 Vern Den Herder 72 Bob Heinz Ti Gilliarn,Jo. OS 15Morrall, Earl 89 Charley Wade LI75 Manny Fernandez 65 Maulty Moore 20 BItter. Rocky RB 23 Wagner, Mike 20Seiple, Larry P-T[ LI79 Wayne Moore 77 Ooug Cruson 76 Willie Young RI72 Bob Heinz 10 Larry Woods $ 21Kiick, Jim 24 Thama*,James CS-S RB LG67 Bob Kuechenberg64 Ed Newman RE84 Bill Stanfill 72 Bob Heinz 25 Shank tin, Ron 22Morris, Mercury RB LIB59 Doug Swift 51 Larry Ball C62 Jim Langer 55 lrv Goode 36 Peenos'i, Preston RB 23Leigh, Charles RB MIB85 Nick Buoniconti 53 Sob Mâtheson RG66 Larry little 55 try Goode 27 Edwards, Glen S 25Foley, urn CB 57 Mike Kolen 58 Bruce Bannon RI73 Norm Evans 77 Doug Crusan RIB 29 Dockery, John CS 26Mumphord, Lloyd CS TE 88 Jim Mandich LCB26 Lloyd Mumphord 25 Tim Foley RB 20Smith, Tom RB 80 Mary Fleming 20 LarrySeiple 32 Harris, Franco RCB45 Curtis Johnson 48 Henry Stuckey 34Sellers, Ron WR WR86 Marlin Briscoe 81 Howard Twilley 33 Puque, John RB FS13 Jake Scoff 49 Charles Babb 34 Russell, Andy LB 36Nottingham, Don RB QB12 Bob Griese 15 Earl Morrall 10Don Strock 35 Davis, Steve RB 39Csonka, Larry RB RB22 Mercury Morris 21 Jim Kiick 23Charles Leigh 5540 Dick Anderson 49 Charles Babb 38 Bradley, Ed LB 40Anderson, Dick 5 RB39 Larry Csonka 36 Don Nottingham 29Tom Smith 39 WaLden, Bobby P 42Worfield, Paul WR 41 Meyer, Dennis S 45Johnson, Curtis CB 43 Lewis, Frank WR 48Stuckey, Henry CB 47 Blount, Mel CB 49Bobb, Charles S Steelors DEFENSE Stealers OFFENSE 48 Rawser, John CB 51 Ball, Lorry LB LE68L.C. -

2013 Steelers Media Guide 5

history Steelers History The fifth-oldest franchise in the NFL, the Steelers were founded leading contributors to civic affairs. Among his community ac- on July 8, 1933, by Arthur Joseph Rooney. Originally named the tivities, Dan Rooney is a board member for The American Ireland Pittsburgh Pirates, they were a member of the Eastern Division of Fund, The Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation and The the 10-team NFL. The other four current NFL teams in existence at Heinz History Center. that time were the Chicago (Arizona) Cardinals, Green Bay Packers, MEDIA INFORMATION Dan Rooney has been a member of several NFL committees over Chicago Bears and New York Giants. the past 30-plus years. He has served on the board of directors for One of the great pioneers of the sports world, Art Rooney passed the NFL Trust Fund, NFL Films and the Scheduling Committee. He was away on August 25, 1988, following a stroke at the age of 87. “The appointed chairman of the Expansion Committee in 1973, which Chief”, as he was affectionately known, is enshrined in the Pro Football considered new franchise locations and directed the addition of Hall of Fame and is remembered as one of Pittsburgh’s great people. Seattle and Tampa Bay as expansion teams in 1976. Born on January 27, 1901, in Coultersville, Pa., Art Rooney was In 1976, Rooney was also named chairman of the Negotiating the oldest of Daniel and Margaret Rooney’s nine children. He grew Committee, and in 1982 he contributed to the negotiations for up in Old Allegheny, now known as Pittsburgh’s North Side, and the Collective Bargaining Agreement for the NFL and the Players’ until his death he lived on the North Side, just a short distance Association. -

The Loser's Curse: Decision Making and Market Efficiency in the National Football League Draft

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Operations, Information and Decisions Papers Wharton Faculty Research 7-2013 The Loser's Curse: Decision Making and Market Efficiency in the National Football League Draft Cade Massey University of Pennsylvania Richard H. Thaler Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/oid_papers Part of the Marketing Commons, and the Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons Recommended Citation Massey, C., & Thaler, R. H. (2013). The Loser's Curse: Decision Making and Market Efficiency in the National Football League Draft. Management Sciecne, 59 (7), 1479-1495. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/ mnsc.1120.1657 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/oid_papers/170 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Loser's Curse: Decision Making and Market Efficiency in the National Football League Draft Abstract A question of increasing interest to researchers in a variety of fields is whether the biases found in judgment and decision-making research remain present in contexts in which experienced participants face strong economic incentives. To investigate this question, we analyze the decision making of National Football League teams during their annual player draft. This is a domain in which monetary stakes are exceedingly high and the opportunities for learning are rich. It is also a domain in which multiple psychological factors suggest that teams may overvalue the chance to pick early in the draft. Using archival data on draft-day trades, player performance, and compensation, we compare the market value of draft picks with the surplus value to teams provided by the drafted players.