Joint Standing Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scangate Document

P lu n g in g 5 into politics Should sports stars dive in? When you consider what makes a successful politician, three things stand out: to succeed, a politician must be reasonably popular, they should have a fairly high profile, and most important of all, they have to be credible. If that’s basically what it takes, there’s a select band of Australians boots. "Some translate their public standing into lucrative who have all the right qualifications in spades - Australia’s top sponsorship deals, or a career as a commentator," she says. sports people. Jackie Kelly says sitting politicians are lucky that more elite sports Most of our best sportsmen and women boast the sort of profile people don’t attempt to win seats in Parliament. “They’d do very and popularity a politician would kill for, and it seems everything a well,” she says, "at least initially. However, when they came to put sports star utters, no matter how banal, finds its way into the media. themselves up for a second term, they'd be assessed just like every other politician." It’s surprising then that so few of our top athletes have translated their public standing into a political career. The Member for the ACT seat of Fraser, Bob McMullan, has never represented his country in sport, but the Shadow Minister for There are some notable exceptions, among them cycling great Aboriginal Affairs is a self-confessed sports nut. He also knows what Sir Hubert Opperman who represented the seat of Corio in the political parties are looking for in their candidates, having served as House of Representatives between 1949 and 1967, and held an ALP State and National Secretary before entering Parliament. -

Newsletter Issn 0813-5614

VOLUNTARY EUTHANASIA SOCIETY OF NEW SOUTH WALES (INCORPORATED) ACN 002 545 235 Patron: Prof Peter Baume AO FRACP FRACGP Telephone: (02) 9212 4782 NEWSLETTER ISSN 0813-5614 Number 108 March 2006 DR FAYE GIRSH VISITS In October 2005, on her way to Brisbane for the EXIT conference, Dr Faye Girsh came to Sydney to address the VES meeting. Her Contents talk was both interesting and entertaining, greatly appreciated by the members present. Dr Faye Girsh 1 On the Board of the World Federation of Right-to-Die Societies, Dr Girsh also edits the newsletter. ‘What is going on in the world For your diary 3 is very important because there is nothing that happens in Sydney, in Denver where I live, or in Switzerland, that doesn’t affect the Exit Conference 6 rest of us in the movement,’ she told the meeting. While she always AGM Guest Speaker 6 enjoys visiting Australia, Dr Girsh was particularly pleased to be here in 2005, the 10th anniversary of the first voluntary euthanasia Euthanasia's Growing law in the world. Acceptance 7 Dr Girsh spoke about the Australian Federal anti-suicide legislation (which came into effect in January 2006), labelling it ‘an Central Coast News 8 abomination’ and predicting that this Bill will affect everybody in the world – those of us in the movement, but also the broader North Rivers News 8 aspect of civil liberties. ‘At the recent meeting of the World Letter from Holland 9 Federation of the Right-to-Die Societies in Turin, Italy, everybody was very concerned that this could have an affect on other countries, Assisted Suicides in Belgium 9 especially the USA that has the same kind of censorship mentality,’ she said. -

Ministerial Careers and Accountability in the Australian Commonwealth Government / Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis

AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Ministerial careers and accountability in the Australian Commonwealth government / edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis. ISBN: 9781922144003 (pbk.) 9781922144010 (ebook) Series: ANZSOG series Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Politicians--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Ethical behavior. Political ethics--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Public opinion. Australia--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--Public opinion. Other Authors/Contributors: Dowding, Keith M. Lewis, Chris. Dewey Number: 324.220994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents 1. Hiring, Firing, Roles and Responsibilities. 1 Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis 2. Ministers as Ministries and the Logic of their Collective Action . 15 John Wanna 3. Predicting Cabinet Ministers: A psychological approach ..... 35 Michael Dalvean 4. Democratic Ambivalence? Ministerial attitudes to party and parliamentary scrutiny ........................... 67 James Walter 5. Ministerial Accountability to Parliament ................ 95 Phil Larkin 6. The Pattern of Forced Exits from the Ministry ........... 115 Keith Dowding, Chris Lewis and Adam Packer 7. Ministers and Scandals ......................... -

ANU CRAWFORD LEADERSHIP FORUM PROGRAM GLOBAL REALITIES, DOMESTIC CHOICES Rebuilding Trust 23-25 JUNE 2019

ANU CRAWFORD LEADERSHIP FORUM PROGRAM GLOBAL REALITIES, DOMESTIC CHOICES Rebuilding trust 23-25 JUNE 2019 ANU Public Policy and Societal Impact Hub CONTENTS Information 1 Maps 2 Welcome 5 The Forum 3 Convening Group 6 Program 7 After the Forum 16 Breakfast sessions 18 International speakers 24 Domestic speakers 27 Participant list 57 INFORMATION Registration desk Forum App Acton Foyer, JG Crawford Building iPhone - download from iTunes Android - download from Google Play Event support Mel Huggins Forum Website 0498 435 169 http://aclf.anu.edu.au E [email protected] Venues Forum Management National Gallery of Australia Bob McMullan Parkes Pl E, Parkes ACT 2600 Director, ANU Crawford Leadership Forum T 0481 756 525 JG Crawford Building E [email protected] 132 Lennox Crossing, Acton ACT 2601 Lauren Bartsch University House Manager, ANU Crawford Leadership Forum 1 Balmain Crescent, Acton ACT 2601 T 0405 387 960 E [email protected] Llewellyn Hall 100 William Herbert Place, Canberra ACT 2601 ANU media hotline T (02) 6125 7979 E [email protected] James Giggacher 0436 803 488 Twitter #ACLForum Wifi internet access Network: ANU-Secure Username: ANUForum2019 Password: Forum! ANU Security T (02) 6125 2249 Emergency services T 000 1 MAPS Level 2 Plenary Sessions Molonglo Theatre CRAWFORD Breakfast Sessions Common Seminar Rooms 7-9 ANNEX Room Monday Lunch Seminar Rooms 5-9 4 5 Media Room Brindabella Seminar Room 4 Theatre 6 ANU Media Studio Level 2 Common Room 7 Molonglo Theatre LIFT 8 9 Legend Womens toilet Mens toilet LIFT Disabled -

Preselection 2010: the ALP Selects Its Candidate for Fraser

Preselection 2010 The ALP selects its candidate for Fraser Fear and loathing on Anzac eve? For eight aspiring Federal politicians and 241 ALP Members April 24 was the culmination of five weeks of frenetic campaigning. At stake was the labor candidacy for the Federal Division of Fraser. The campaign had been hard and long, though fair and clean. The winner was a youngish gen Xer Andrew Leigh, a professor of economics at the ANU. Voting took place at the Polish White Eagle Club in the inner northern suburb of Turner on a cold showery day, verifying the old Canberra adage that winter starts on Anzac day. In the weeks from the announcement of the preselection to preselection day the eight candidates devoted themselves to winning over the hearts and minds of pre selectors. Campaigning was intense and redefined to new levels of sophistication. How did Andrew Leigh win? Or why did the other seven lose? This is the story of that campaign. Fraser always labor The Federal Division of Fraser covers Canberra’s north side1 plus the Jervis Bay territory. It comprises the three communities of Belconnen, Gungahlin and North Canberra. The division was created in 1974 when the old ACT electorate was split in two, the Division of Canberra covered most of the south side. For a brief period 1996 to 1997 the ACT was divided into three Divisions with Fraser covering the more northern parts of the ACT. It was named after highly regarded Jim (James) Fraser who was the ALP member for the ACT from 1951 to 1970. -

Political Chronicles

Australian Journal of Politics and History: Volume 54, Number 2, 2008, pp. 289-341. Political Chronicles Commonwealth of Australia July to December 2007 JOHN WANNA The Australian National University and Griffith University The Stage, the Players and their Exits and Entrances […] All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances; [William Shakespeare, As You Like It] In the months leading up to the 2007 general election, Prime Minister John Howard waited like Mr Micawber “in case anything turned up” that would restore the fortunes of the Coalition. The government’s attacks on the Opposition, and its new leader Kevin Rudd, had fallen flat, and a series of staged events designed to boost the government’s stocks had not translated into electoral support. So, as time went on and things did not improve, the Coalition government showed increasing signs of panic, desperation and abandonment. In July, John Howard had asked his party room “is it me” as he reflected on the low standing of the government (Australian, 17 July 2007). Labor held a commanding lead in opinion polls throughout most of 2007 — recording a primary support of between 47 and 51 per cent to the Coalition’s 39 to 42 per cent. The most remarkable feature of the polls was their consistency — regularly showing Labor holding a 15 percentage point lead on a two-party-preferred basis. Labor also seemed impervious to attack, and the government found it difficult to get traction on “its” core issues to narrow the gap. -

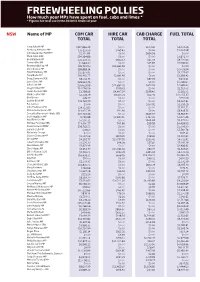

Freewheeling Pollies How Much Your Mps Have Spent on Fuel, Cabs and Limos * * Figures for Total Use in the 2010/11 Financial Year

FREEWHEELING POLLIES How much your MPs have spent on fuel, cabs and limos * * Figures for total use in the 2010/11 financial year NSW Name of MP COM CAR HIRE CAR CAB CHARGE FUEL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL Tony Abbott MP $217,866.39 $0.00 $103.42 $4,559.36 Anthony Albanese MP $35,123.59 $265.43 $0.00 $1,394.98 John Alexander OAM MP $2,110.84 $0.00 $694.56 $0.00 Mark Arbib SEN $34,164.86 $0.00 $0.00 $2,806.77 Bob Baldwin MP $23,132.73 $942.53 $65.59 $9,731.63 Sharon Bird MP $1,964.30 $0.00 $25.83 $3,596.90 Bronwyn Bishop MP $26,723.90 $33,665.56 $0.00 $0.00 Chris Bowen MP $38,883.14 $0.00 $0.00 $2,059.94 David Bradbury MP $15,877.95 $0.00 $0.00 $4,275.67 Tony Burke MP $40,360.77 $2,691.97 $0.00 $2,358.42 Doug Cameron SEN $8,014.75 $0.00 $87.29 $404.41 Jason Clare MP $28,324.76 $0.00 $0.00 $1,298.60 John Cobb MP $26,629.98 $11,887.29 $674.93 $4,682.20 Greg Combet MP $14,596.56 $749.41 $0.00 $1,519.02 Helen Coonan SEN $1,798.96 $4,407.54 $199.40 $1,182.71 Mark Coulton MP $2,358.79 $8,175.71 $62.06 $12,255.37 Bob Debus $49.77 $0.00 $0.00 $550.09 Justine Elliot MP $21,762.79 $0.00 $0.00 $4,207.81 Pat Farmer $0.00 $0.00 $177.91 $1,258.29 John Faulkner SEN $14,717.83 $0.00 $0.00 $2,350.51 Mr Laurie Ferguson MP $14,055.39 $90.91 $0.00 $3,419.75 Concetta Fierravanti-Wells SEN $20,722.46 $0.00 $649.97 $3,912.97 Joel Fitzgibbon MP 9,792.88 $7,847.45 $367.41 $2,675.46 Paul Fletcher MP $7,590.31 $0.00 $464.68 $2,475.50 Michael Forshaw SEN $13,490.77 $95.86 $98.99 $4,428.99 Peter Garrett AM MP $39,762.55 $0.00 $0.00 $1,009.30 Joanna Gash MP $78.60 $0.00 -

From Westernport to India

FROM WESTERNPORT TO INDIA FROM WESTERNPORT TO INDIA Address by the Hon Gareth Evans QC, Minister for Foreign Affairs, to Westernport Export Foundation's Seminar Dinner, 27 February 1996 _______________________________________________________________________ It is a great pleasure to be back here tonight wearing one of my favourite local hats, as Chairman of the Westernport Export Foundation, and to be joining with you in our joint efforts to boost the export performance of the South East region. This is the first of three seminars that the Foundation will hold, to help small to medium enterprises get a better understanding of the menu of Government services they can use to develop their export potential. The key to the value of these seminars is practical advice and assistance - as well as informal networking with others who are seeking to initiate or expand their export business. We are all in the business of finding new business these days, and when you're a small or medium sized enterprise getting into export, it is just plain good sense to be taking advantage of the advice, experience and potential joint venture support of others in our region. The Foundation is very much in the game of helping with those advice and information flows, and helping individual firms find partners with whom to venture offshore together. Each of the seminars has a special country focus. Later seminars will deal with South Africa and Indonesia. But the focus today has been on India. The story is a very exciting and encouraging one: India itself is undergoing a very dramatic transformation and the potential for Australian companies in India is virtually unlimited. -

10-12.Pdf (347.5Kb)

POLITICS and gentle in one setting, cruelly arrogant in another. There is Keating the Fascinator a telling aphorism, Watsonian in form but Keating in sub- stance: ‘one cannot warrant the truth of one’s position by succumbing to the prejudice of fools.’ Neal Blewett Keating was incorrigibly wilful. ‘Put an open gate in front of him and he would not go through it; put a fence and he’d Don Watson try to jump it.’ Increasingly, as his premiership waned, ‘he Recollections of a Bleeding Heart: would not react to a serious challenge [in domestic politics] until he felt the shadow of the axe above him’. This became A Portrait of Paul Keating PM very much a problem for his minders. ‘Years of death-defying Knopf, $45hb, 756pp, 0 091 83517 8 struggle had given him the metabolism of a cornered rat — he could not get excited until the stakes were very high, HAT IS IT about Paul Keating that so fascinated preferably a matter of life and death.’ And yet sadness hung his retainers? Six years ago, John Edwards wrote about him. He could, as I know, be the most exuberant of men, Wa massive biography-cum-memoir taking Keating’s yet melancholy was never far away. Indeed, it was this sense story to 1993. Now Don Watson has produced an even of sadness that, for Watson, remains the dominant impres- heftier tome. Narrower in chronological span — 1992 to 1996 sion, perhaps even a sense of mourning, which ‘empties the — Watson is broader in his interests, more personal, mourner’s world, leaving it like an abandoned house’. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

ADDENDA All dates are 1994 unless stated otherwise EUROPEAN UNION. Entry conditions for Austria, Finland and Sweden were agreed on 1 March, making possible these countries' admission on 1 Jan. 1995. ALGERIA. Mokdad Sifi became Prime Minister on 11 April. ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA. At the elections of 8 March the Antigua Labour Party (ALP) gained 11 seats. Lester Bird (ALP) became Prime Minister. AUSTRALIA. Following a reshuffle in March, the Cabinet comprised: Prime Minis- ter, Paul Keating; Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Housing and Regional Development, Brian Howe; Minister for Foreign Affairs and Leader of the Govern- ment in the Senate, Gareth Evans; Trade, Bob McMullan; Defence, Robert Ray; Treasurer, Ralph Willis; Finance and Leader of the House, Kim Beazley; Industry, Science and Technology, Peter Cook; Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, Nick Bolkus; Employment, Education and Training, Simon Crean; Primary Industries and Energy, Bob Collins; Social Security, Peter Baldwin; Industrial Relations and Transport, Laurie Brereton; Attorney-General, Michael Lavarch; Communications and the Arts and Tourism, Michael Lee; Environment, Sport and Territories, John Faulkner; Human Services and Health, Carmen Lawrence. The Outer Ministry comprised: Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, Robert Tickner; Special Minister of State (Vice-President of the Executive Council), Gary Johns; Develop- ment Co-operation and Pacific Island Affairs, Gordon Bilney; Veterans' Affairs, Con Sciacca; Defence Science and Personnel, Gary Punch; Assistant Treasurer, George Gear; Administrative Services, Frank Walker; Small Businesses, Customs and Construction, Chris Schacht; Schools, Vocational Education and Training, Ross Free; Resources, David Beddall; Consumer Affairs, Jeannette McHugh; Justice, Duncan Kerr; Family Services, Rosemary Crowley. -

2. Ministers As Ministries and the Logic of Their Collective Actiontable

2. Ministers as Ministries and the Logic of their Collective Action John Wanna As recounted in the opening chapter, ministerial responsibility is primarily understood and studied as a formal accountability process with the emphasis largely on individual ministerial accountability and the occasional resignation. This preoccupation with individual responsibility reflects a British obsession with the behaviour of the particular minister (Dowding and Kang 1998; Woodhouse 1994) or a scepticism of the observance of collective responsibility, especially when governments disintegrate—the so-called ‘myth/fallacy’ argument (see Dell 1980; Weller 1985). There is generally less attention paid to the dimensions of collective ministerial responsibility and the politics of maintaining cohesion, other than the seminal acknowledgment by constitutionalists of the need for cabinet solidarity in modern parliamentary government (Crisp 1973, 353; Dicey 1885; Jennings 1959), and the incantation of the political requirement in modern- day ministerial codes (see Australian Government, Cabinet Handbook, 2009, ss. 15–24). Collective ministerial responsibility is arguably a far less formal form of accountability, interpreted largely by the prime minister, and exercised through political expedience, some malleable conventions and frequent reinterpretation. Moreover, collective responsibility is defined and given expression not only in the (positive) requirements for collegial solidarity, but also in the degree of latitude shown to dissention and to breaches of the principles. As will be explored below, ministers are political actors who are simultaneously individual and collective entities. They play out these dual but overlapping roles across a range of interactions in which they more or less engage. These interactions occur with their contemporaries at the centre of government (around cabinet and its political, symbolic and decision-making processes), in their relations with senior officials and their departments, with the public service and media and with the wider community. -

Labor and Financial Deregulation

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Labor and financial deregulation: the Hawke/Keating governments, banking and new labor Stephen Martin University of Wollongong Martin, Stephen, Labor and financial deregulation: the Hawke/Keating governments, banking and new labor, PhD, Department of Economics, Department of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/319 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/319 NOTE This online version of the thesis may have different page formatting and pagination from the paper copy held in the University of Wollongong Library. UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG COPYRIGHT WARNING You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. LABOR AND FINANCIAL DEREGULATION The Hawke/Keating Governments, Banking and New Labor A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Stephen Martin B.A.