Getting the Girl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War I After-Effects Still Being Felt Today

TODAY’S WEATHER Today: Mostly cloudy through mid-morning, Friday, April 7, 2017 then gradual clearing. Vol. 4, No. 66 Tonight: Mostly clear. Patchy frost after 5 a.m. Sheridan, Noblesville, Cicero, Arcadia, Atlanta, Carmel, Fishers, Westfield HIGH: 51 LOW: 33 World War I after-effects still being felt today By FRED SWIFT weapons like land mines and mustard gas. at the Noblesville library on not come out of World War I. It was started World War I, billed as "the war to end In Hamilton County and much of Thursday evening. Although from a German in 1899 by Spanish-American War vets.) all wars" which America it has become almost a forgotten family, Mueller served in the U.S. Army. The after-effects of WWI were long- obviously it wasn't, war. Locally, there were only 29 men who Another Noblesville participant, Frank lasting and in the case of the great influenza started for the U.S. lost their lives, many fewer than in what we Huntzinger, was the first local man killed in epidemic, more deadly than the battlefield. 100 years ago this think of as "big" wars like the Civil War, the war. The Frank Huntzinger American Although never directly attributed to the week. Many folks World War II and Vietnam. The names of Legion Post 45 was named in his honor. The war, the flu first show up in the U.S. at an don't realize it was all all are found on the Veterans Memorial on Legion nationwide was founded in 1919 by army base in Kansas where soldiers were over in 19 months. -

LSU LADY TIGERS (11-0, 1-0 SEC) Auburn Head Coach: Nell Fortner School Record: 25-17 (2Nd Year) No

TONIGHT’S GAME QUICK FACTS Game #12 LSU head coach: Pokey Chatman Chatman’s career record: 44-3 (2nd year) Chatman’s LSU record: 44-3 (2nd year) LSU LADY TIGERS (11-0, 1-0 SEC) Auburn head coach: Nell Fortner School record: 25-17 (2nd year) No. 3 AP/No. 3 Coaches Career record: 42-28 (3rd year) at Series record: Auburn leads 26-11 and 12-4 in games played in Auburn. AUBURN (9-4, 0-0 SEC) Last meeting: LSU defeated Auburn 62-57 on Feb. 20, 2005 in Auburn. NR AP/NR Coaches Television: Fox Sports Net (Leah Secondo and Debbie Antonelli) Jan. 4, 2006 • Beard-Eaves Memorial Coliseum (10,500) Satellite feed: none Radio: LSU Sports Radio Network (Patrick Auburn, Ala. • 8 p.m. CST • SEC-TV Wright and Brian Miller) LADY TIGERS PROBABLE STARTERS Officials: Scott Yarbrough, Eric Brewton, G 12 RaShonta LeBlanc 5-7 So. 5.1 ppg 2.9 rpg 3.9 apg Kim Watt • Has started all 11 games this season LSU Sports Information: Brian Miller G 32 Scholanda Hoston 5-10 Sr. 8.1 ppg 1.9 rpg 3.4 apg O: (225) 578-8204 C: (225) 939-0204 • Started 60 games in her career Auburn Sports Information: Mendy Nestor G 33 Seimone Augustus 6-1 Sr. 19.6 ppg 5.3 rpg 58.4 FG% O: (334) 844-9900 C: (334) 750-1387 • Started all 116 games of her career F 22 Florence Williams 6-1 Sr. 5.5 ppg 3.1 rpg 1.5 apg • Has started all 11 games this season SCHEDULE/RESULTS C 34 Sylvia Fowles 6-6 So. -

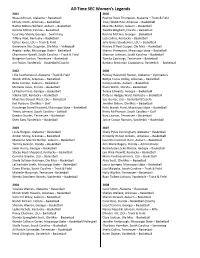

All-Time List Layout 1

All‐Time SEC Women’s Legends 2001 2005 Niesa Johnson, Alabama – Basketball Pauline Davis Thompson, Alabama – Track & Field Christy Smith, Arkansas – Basketball Tracy Webb Rice, Arkansas – Basketball Ruthie Bolton‐Holifield, Auburn – Basketball Mae Ola Bolton, Auburn – Basketball Delisha Milton, Florida – Basketball Talatha Bingham, Florida – Basketball Courtney Shealy, Georgia – Swimming Katrina McClain, Georgia – Basketball Tiffany Wait, Kentucky – Basketball Lisa Collins, Kentucky – Basketball Esther Jones, LSU – Track & Field Julie Gross Stoudemire, LSU – Basketball Genevieve Shy Chapman, Ole Miss – Volleyball Kimsey O’Neal Cooper, Ole Miss – Basketball Angela Taylor, Mississippi State – Basketball Sharon Thompson, Mississippi State – Basketball Charmaine Howell, South Carolina – Track & Field Shannon Johnson, South Carolina – Basketball Bridgette Gordon, Tennessee – Basketball Tamika Catchings, Tennessee – Basketball Jim Foster, Vanderbilt – Basketball (Coach) Barbara Brackman Capobianco, Vanderbilt – Basketball 2002 2006 Lillie Leatherwood, Alabama –Track & Field Penney Hauschild Buxton, Alabama – Gymnastics Wendi Willits, Arkansas – Basketball Bettye Fiscus Dickey, Arkansas – Basketball Reita Clanton, Auburn – Basketball Carolyn Jones, Auburn – Basketball Merlakia Jones, Florida – Basketball Paula Welch, Florida – Basketball La’Keshia Frett, Georgia – Basketball Teresa Edwards, Georgia – Basketball Valerie Still, Kentucky – Basketball Patty Jo Hedges Ward, Kentucky – Basketball Madeline Doucet West, LSU – Basketball Sue Gunter, -

Northwesternwomen's Basketball

NORTHWESTERN WOMEN’S BASKETBALL Anderson Hall | 1501 Central Street | Evanston, IL 60208 Athletic Communications 2016-17 Quick Facts 1501 Central St. | Evanston, IL 60208 | Phone: (847) 491-7503 | Fax: (847) 491-8818 Primary Contact: Carsten Parmenter Location: ........................................................................Evanston, Ill. Email: [email protected] | Office: (847) 467-3724 Founded:....................................................................................... 1851 Enrollment: ...............................................................................8,367 President: .............................................................. Morton Schapiro 2016-17 roster Home Facility: ...................................................Welsh-Ryan Arena Capacity: .......................................................................................8,117 Nickname: ........................................................................... Wildcats NO. NAME POS. HT. ELIG. HOMETOWN/HIGH SCHOOL Colors: ................................................................... Purple and White 3 Ashley Deary * G 5-4 Sr. Flower Mound, Texas / Flower Mound Conference: ........................................................................... Big Ten 4 Bry Hopkins F 6-2 Fr. Palatine, Ill. / William Fremd Director of Athletics: .............................................Dr. Jim Phillips 5 Jordan Hankins G 5-8 So. Indianapolis, Ind. / Lawrence North Sport Administrator: .................................................. -

Good Drafting Makes Good Contracts

Good Drafting Makes Good Contracts by Martin J. Greenberg, Greenberg & Hoeschen, LLC, Milwaukee, WI Sports contracts deserve the same precision of draftsmanship as any other legal document. When drafting sports contracts, our goal as lawyers should be precision and expression conferring a singular meaning. The document should be clear on its face so that it is not subject to third-party intervention. In essence, when drafting sports contracts we should adopt the principle of S.U.C.S. (Simplicity – Martin Greenberg Understanding – Clarity - Standardization) or K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple Stupid).1 Although the principles of S.U.C.S. have been promoted for over a decade, parties today continue to violate them while drafting sports contracts. Mistakes particular to sports contracts are repeated, resulting in mediation or arbitration between the parties.2 Recently, Louisiana State University learned first hand why sports contracts, perhaps even more than others, must be drafted with particular attention to the principles of S.U.C.S. Pokey Chatman (Chatman) was an integral part of the Louisiana State University (LSU) women’s basketball program as a player and a coach for 17 years. Chatman was a point guard for LSU from 1988 until 1991 and in 1991 received Kodak All-American honors in her senior year.3 During the 2003-04 basketball season, Chatman was appointed LSU’s interim head coach replacing the legendary Sue Gunter. As acting head coach, the Lady Tigers finished the 2003-04 regular season with a 15-5 record and ended the season in the women’s Final Four. -

Women's Basketball Award Winners

WOMEN’S BASKETBALL AWARD WINNERS All-America Teams 2 National Award Winners 15 Coaching Awards 20 Other Honors 22 First Team All-Americans By School 25 First Team Academic All-Americans By School 34 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners By School 39 ALL-AMERICA TEAMS 1980 Denise Curry, UCLA; Tina Division II Carla Eades, Central Mo.; Gunn, BYU; Pam Kelly, Francine Perry, Quinnipiac; WBCA COACHES’ Louisiana Tech; Nancy Stacey Cunningham, First selected in 1975. Voted on by the Wom en’s Lieberman, Old Dominion; Shippensburg; Claudia Basket ball Coaches Association. Was sponsored Inge Nissen, Old Dominion; Schleyer, Abilene Christian; by Kodak through 2006-07 season and State Jill Rankin, Tennessee; Lorena Legarde, Portland; Farm through 2010-11. Susan Taylor, Valdosta St.; Janice Washington, Valdosta Rosie Walker, SFA; Holly St.; Donna Burks, Dayton; 1975 Carolyn Bush, Wayland Warlick, Tennessee; Lynette Beth Couture, Erskine; Baptist; Marianne Crawford, Woodard, Kansas. Candy Crosby, Northern Ill.; Immaculata; Nancy Dunkle, 1981 Denise Curry, UCLA; Anne Kelli Litsch, Southwestern Cal St. Fullerton; Lusia Donovan, Old Dominion; Okla. Harris, Delta St.; Jan Pam Kelly, Louisiana Tech; Division III Evelyn Oquendo, Salem St.; Irby, William Penn; Ann Kris Kirchner, Rutgers; Kaye Cross, Colby; Sallie Meyers, UCLA; Brenda Carol Menken, Oregon St.; Maxwell, Kean; Page Lutz, Moeller, Wayland Baptist; Cindy Noble, Tennessee; Elizabethtown; Deanna Debbie Oing, Indiana; Sue LaTaunya Pollard, Long Kyle, Wilkes; Laurie Sankey, Rojcewicz, Southern Conn. Beach St.; Bev Smith, Simpson; Eva Marie St.; Susan Yow, Elon. Oregon; Valerie Walker, Pittman, St. Andrews; Lois 1976 Carol Blazejowski, Montclair Cheyney; Lynette Woodard, Salto, New Rochelle; Sally St.; Cindy Brogdon, Mercer; Kansas. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Media Information Southeastern Conference 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS Media Information Southeastern Conference 2.................................................................Vanderbilt Athletic Communications 51...................... Vanderbilt’s All-Time SEC Finishes/2013-14 Award Winners 3................................................................................. Covering the Commodores 52........................................................................How VU Stacked Up in 2013-14 52................................................................All-Time SEC Champions/Standings Season Outlook 4..................................................................................................................... Roster NCAA Tournament 5............................................................................................................Quick Facts 53.......................................................................... SEC in the NCAA Tournament 6-7 ................................................................................................Season Preview 54................................................................................Vanderbilt’s NCAA Results Player Information (Listed By Jersey Number) History & Records 8................................................................................................ Rebekah Dahlman 55..................................................................................... Vanderbilt in the Top 25 9...................................................................................................Jasmine Jenkins -

E-Zine April 2005

e-Zine April 2005 by Mel Greenberg INSIDE SCOOP™… Generational Finals And so here we are in has made the Owls into a Indianapolis, at a most unique nationally-ranked team that also Women’s Final Four, one that had a 25-game win streak until promises to be a little more Rutgers applied the brakes in the sedate with the party crowd than second round of the tournament. last year’s raucous doings in New Orleans. Meanwhile, Michigan State and Baylor are both here for the first This may be remembered as the time, and Louisiana State is here generational finals for one simple for a second time after making a reason: the NCAA Women’s debut last season. Tournament will reach its 25th birthday next season. It could be a big weekend for LSU in the RCA Dome, especially if Appropriately, the kid star players former coach Sue Gunter is named of the early days of NCAA to the Naismith Basketball Hall of competition back in 1982 are now Fame class of 2005 to be becoming the forefront of a new announced on April 4. generation of talented and successful coaches. WNBA Houston Comets and former Mississippi coach Van Consider this: In the spring of Chancellor, who was the winning 2000, former Louisiana Tech star U.S. Olympic coach in Athens, is Kim Mulkey-Robertson was hired also a candidate for induction. at Baylor, Dawn Staley was hired at Temple, and Joanne P. McCallie Pat Summitt of Tennessee, was lured into Michigan State. already a Hall of Famer, is still All three programs were nowhere around after setting a new NCAA on the map of prominent women’s career record for men and basketball at the time. -

SEC News Cover.Qxp

CoSIDA NEWS Intercollegiate Athletics News from Around the Nation May 7, 2007 Paying coaches big dollars just makes sense for colleges Page 1 of 2 http://www.baltimoresun.com/sports/college/bal-sp.whitley29apr29,0,7964613.story?coll=bal-college-sports From the Baltimore Sun Paying coaches big dollars just makes sense for colleges April 29, 2007 The year's most astounding sports number came out of Tuscaloosa last weekend: 92,138. That's how many fans showed up at Alabama's spring football game. I don't know whether to laugh, cry or invest in Nick Saban's new clothing line. I do know it should answer the concerns of people who think certain university employees are wildly overpaid. "You have to ask the hard questions," NCAA president Myles Brand said. "Is it the appropriate thing to do within the context of college sports?" He was responding to a question about the gold mine Kentucky was ready to dig for Florida basketball coach Billy Donovan. That came after Saban got his $4-million-a-year windfall. And in this week's affront to academic integrity, Rutgers announced its women's basketball coach is going to be making as much as its football coach. It will be interesting to see whether there's the same outcry when a woman cashes in, but that's beside the point. The point is that if anyone still is looking at this in the context of college sports, they hopelessly are blind to reality. The reality is that college sports is an increasingly gargantuan business. -

Chicago Sky 2016 Game Notes Game 8 • Home Game 4 June 3, 2016

Chicago Sky 2016 Game Notes Game 8 • Home Game 4 June 3, 2016 2016 SKY SCHEDULE/RESULTS CHICAGO SKY (3-4) DATE DAY OPPONENT TIME/W-L REC TOP SCORER versus May 1 Sun. NEW YORK (Exh.) W, 93-59 - Delle Donne (17 pts) May 4 Wed. at Connecticut (Exh.) L, 84-81 Delle Donne (13 pts) WASHINGTON MYSTICS (2-5) May 5 Thu. ATLANTA (Exh.) W, 95-75 Laney (15 pts) Rosemont, IL (Allstate Arena) Tip: 7:30 pm CDT May 14 Sat. CONNECTICUT W, 93-70 1-0 Vandersloot (14 pts) • The U Too (Eric Collins- pxp, Stephen Bardo - color) May 18 Wed. MINNESOTA L, 97-80 1-1 Delle Donne (28 pts) May 22 Sun. at Atlanta L, 87-81 1-2 Pondexter (17 pts) • @wnbachicagosky • @WashMystics May 24 Tue. LOS ANGELES L, 93-80 1-3 Faulkner (17 pts) May 27 Fri. at San Antonio L, 79-78 1-4 Delle Donne (27 pts) May 29 Sun. at Dallas W, 92-87 2-4 Pondexter (18 pts) 2016 STATS COMPARISON June 1 Wed. at Washington W, 86-78 3-4 Delle Donne (18 pts) June 3 Fri. WASHINGTON 7:30 PM Chicago Washington June 10 Fri. at Indiana 6:00 PM Points Per Game 84.3 77.6 June 12 Sun. at Phoenix 5:00 PM Opponents PPG 84.4 86.9 June 14 Tue. at Los Angeles 9:30 PM Field Goal % .469 .424 June 17 Fri. at Atlanta 6:30 PM Opponents FG % .411 .455 June 21 Tue. SAN ANTONIO 7:00 PM 3-Point % .323 .354 June 24 Fri. -

Sky Logistics

@wnbachicagosky | chicagosky.net #10FOROURTOWN TABLE OF CONTENTS General Information 2015 Opponent Quar- 2010 Stats Spotters Chart ter-by-Quarter Shooting 2010 Game by Game Results Sky General Info/Training 2015 Scoring by Quarter 2009 Stats 2017 Sky Season Schedule 2015 Regular Season Box 2009 Game by Game Results Allstate Arena Scores 2008 Stats In-Game Entertainment 2008 Game by Game Results Sky in the Community 2007 Stats Sky Cares Sky History 2007 Game by Game Results WNBA Cares Franchise Firsts 2006 Stats Draft History 2006 Game by Game Results Front Office Honor Roll/All-Time Records Playoff History Principal Owner, Michael Alter All-time Leaders Owner, John Rogers The WNBA Leaders by Year Chairman/Minority Owner, Margaret Atlanta Dream All-Time Transactions Stender Connecticut Sun 2016 Stats President & CEO, Adam Fox Indiana Fever 2016 Game by Game Results Chief Financial Officer, Rommel Famatid Los Angeles Sparks 2015 Stats Minnesota Lynx Coaches and Trainers 2015 Game by Game Results New York Liberty General Manager & Head Coach, Amber 2014 Stats Phoenix Mercury Stocks 2014 Game by Game Results San Antonio Stars Assistant Coach, Carlene Mitchell 2013 Stats Seattle Storm Assistant Coach, Carla Morrow 2013 Game by Game Results Dallas Wings Advanced Scout, Kelly Schumacher-Rai- 2012 Stats Washington Mystics mon 2012 Game by Game Results Head Athletic Trainer, Jess Cohen 2011 Stats Stength & Conditioning Coach, Ann 2011 Game by Game Results Crosby 2017 Chicago Sky Team The Players Recent Transactions 2016 Regular Season Review Sky -

LSU LADY TIGERS (5-0, 0-0 SEC) OSU Head Coach: Jim Foster School Record: 79-25 (4Th Year) No

TONIGHT’S GAME QUICK FACTS Game #6 LSU head coach: Pokey Chatman Chatman’s career record: 38-3 (2nd year) Chatman’s LSU record: 38-3 (2nd year) LSU LADY TIGERS (5-0, 0-0 SEC) OSU head coach: Jim Foster School record: 79-25 (4th year) No. 3 AP/No. 3 Coaches Career record: 583-250 (28th year) at Series record: LSU leads 2-1 Last meeting: LSU defeated OSU 97-78 on OHIO STATE (6-0, 0-0 Big Ten) Dec. 18, 1990 in Baton Rouge. Television: ESPN2 (Pam Ward and Ann No. 4 AP/No. 4 Coaches Meyers) Satellite feed: none Dec. 15, 2005 • Value City Arena (19,200) Radio: LSU Sports Radio Network (Patrick Wright and Brian Miller) Columbus, Ohio • 6:30 p.m. CST Officials: N/A LADY TIGERS PROBABLE STARTERS LSU Sports Information: Brian Miller G 12 RaShonta LeBlanc 5-7 So. 5.0 ppg 2.4 rpg 4.0 apg O: (225) 578-8204 C: (225) 939-0204 • Has started all five games this season OSU Sports Information: Pat Kindig G 32 Scholanda Hoston 5-10 Sr. 5.8 ppg 1.6 rpg 3.8 apg O: (614) 292-3577 C: (614) 216-0540 • Started 54 games in her career G 33 Seimone Augustus 6-1 Sr. 21.6 ppg 6.0 rpg 2.2 spg • Started all 110 games of her career F 22 Florence Williams 6-1 Sr. 5.2 ppg 3.4 rpg 1.6 spg SCHEDULE/RESULTS • Has started all five games this season C 34 Sylvia Fowles 6-6 So.