Soccer Coaching Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019Collegealmanac 8-13-19.Pdf

college soccer almanac Table of Contents Intercollegiate Coaching Records .............................................................................................................................2-5 Intercollegiate Soccer Association of America (ISAA) .......................................................................................6 United Soccer Coaches Rankings Program ...........................................................................................................7 Bill Jeffrey Award...........................................................................................................................................................8-9 United Soccer Coaches Staffs of the Year ..............................................................................................................10-12 United Soccer Coaches Players of the Year ...........................................................................................................13-16 All-Time Team Academic Award Winners ..............................................................................................................17-27 All-Time College Championship Results .................................................................................................................28-30 Intercollegiate Athletic Conferences/Allied Organizations ...............................................................................32-35 All-Time United Soccer Coaches All-Americas .....................................................................................................36-85 -

2021 Record Book 5 Single-Season Records

PROGRAM RECORDS TEAM INDIVIDUAL Game Game Goals .......................................................11 vs. Old Dominion, 10/1/71 Goals .................................................. 5, Bill Hodill vs. Davidson, 10/17/42 ............................................................11 vs. Richmond, 10/20/81 Assists ................................................. 4, Damian Silvera vs. UNC, 9/27/92 Assists ......................................................11 vs. Virginia Tech, 9/14/94 ..................................................... 4, Richie Williams vs. VCU, 9/13/89 Points .................................................................... 30 vs. VCU, 9/13/89 ........................................... 4, Kris Kelderman vs. Charleston, 9/10/89 Goals Allowed .................................................12 vs. Maryland, 10/8/41 ...........................................4, Chick Cudlip vs. Wash. & Lee, 11/13/62 Margin of Victory ....................................11-0 vs. Old Dominion, 10/1/71 Points ................................................ 10, Bill Hodill vs. Davidson, 10/17/42 Fastest Goal to Start Match .........................................................11-0 vs. Richmond, 10/20/81 .................................:09, Alecko Eskandarian vs. American, 10/26/02* Margin of Defeat ..........................................12-0 vs. Maryland, 10/8/41 Largest Crowd (Scott) .......................................7,311 vs. Duke, 10/8/88 *Tied for 3rd fastest in an NCAA Soccer Game Largest Crowd (Klöckner) ......................7,906 -

Men's Award Winners

Men’s Award Winners Division I First-Team All-Americans (1910-2012) ................................................ 2 Division I First-Team All-Americans by School ..................................................... 6 Division II First-Team All-Americans (1981-2012) ................................................ 10 Division II First-Team All-Americans by School ..................................................... 11 Division III First-Team All-Americans (1981-2012) ................................................ 12 Division III First-Team All-Americans by School ..................................................... 13 National Award Winners ........................... 15 2 2013 MEN'S SOCCER RECORDS - All-AMERICA TEams All-America Teams NOTE: The All-America teams were SPRING 1914 F–Francis Righter, Cornell D–William Lingelbach, Penn selected by the various team cap- G–Arthur Jackson, Princeton F–J. Moulton Thomas, Princeton D–H. Bradley Sexton, Princeton tains of the Intercollegiate Associa- D–Thomas Elkinton, Haverford F–C.J. Woodridge, Princeton F–Depler Bullard, Lehigh D–Henry Francke, Harvard F–Dick Marshall, Penn St. tion Football League for the 1909- D–Francis Grant, Harvard 1922 F–George Olditch, Cornell 10 season. Various team managers D–Shepard, Yale G–J. Crossan Cooper, Princeton F–Henry Rudy, Swarthmore selected the team from the 1910-11 D–Clement Webster, Penn D–Bayard Amelia, Penn F–Smith, Yale season until 1917. No teams were F–John Bell, Penn D–David Beard, Penn selected in 1918 or 1919 due to F–Shanholt, Columbia D–John Smart, Princeton 1929 World War I. From 1926 to 1940, the F–Samuel Stokes, Haverford D–John Sullivan, Harvard G–Bob McCune, Penn St. F–Tripp, Yale D–Elliot Thompson, Cornell teams were selected by coaches D–Herb Allen, Penn St. F–Walter Weld, Harvard F–Randolph Heizer, Harvard D–William Frazier, Haverford from the Intercollegiate Soccer F–N. -

Messi, Ronaldo, and the Politics of Celebrity Elections

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Research Online Messi, Ronaldo, and the politics of celebrity elections: voting for the best soccer player in the world LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/101875/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Anderson, Christopher J., Arrondel, Luc, Blais, André, Daoust, Jean François, Laslier, Jean François and Van Der Straeten, Karine (2019) Messi, Ronaldo, and the politics of celebrity elections: voting for the best soccer player in the world. Perspectives on Politics. ISSN 1537-5927 https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719002391 Reuse Items deposited in LSE Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the LSE Research Online record for the item. [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ Messi, Ronaldo, and the Politics of Celebrity Elections: Voting For the Best Soccer Player in the World Christopher J. Anderson London School of Economics and Political Science Luc Arrondel Paris School of Economics André Blais University of Montréal Jean-François Daoust McGill University Jean-François Laslier Paris School of Economics Karine Van der Straeten Toulouse School of Economics Abstract It is widely assumed that celebrities are imbued with political capital and the power to move opinion. To understand the sources of that capital in the specific domain of sports celebrity, we investigate the popularity of global soccer superstars. -

Major League Soccer-Historie a Současnost Bakalářská Práce

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sportovních studií Katedra sportovních her Major League Soccer-historie a současnost Bakalářská práce Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Vypracoval: Mgr. Pavel Vacenovský Zdeněk Bezděk TVS/Trenérství Brno, 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně a na základě literatury a pramenů uvedených v použitých zdrojích. V Brně dne 24. května 2013 podpis Děkuji vedoucímu bakalářské práce Mgr. Pavlu Vacenovskému, za podnětné rady, metodické vedení a připomínky k této práci. Úvod ........................................................................................................................ 6 1. FOTBAL V USA PŘED VZNIKEM MLS .................................................. 8 2. PŘÍPRAVA NA ÚVODNÍ SEZÓNU MLS ............................................... 11 2.1. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 17. října 1995..................................... 12 2.2. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 18. října 1995..................................... 14 2.3. První sponzoři MLS ............................................................................... 15 2.4. Platy Marquee players ............................................................................ 15 2.5. Další události v roce 1995 ...................................................................... 15 2.6. Drafty MLS ............................................................................................ 16 2.6.1. 1996 MLS College Draft ................................................................. 17 2.6.2. 1996 MLS Supplemental Draft ...................................................... -

MLS Game Guide

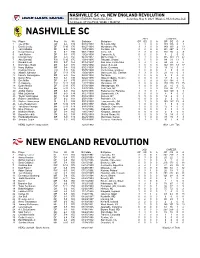

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

20 17 20 18 Men's Soccer Records Book

Men’s Soccer Records Book 20 20 17 18 Men’s Soccer TABLE OF CONTENTS All-time Ivy Champions .........................................1 Ivy Standings .....................................................2-6 Individual Records ................................................7 Team Records .......................................................8 Ivy League Teams in NCAA play ......................9-10 Ivy League Weekly Award Winners................11-13 Ivy League Players & Rookies of the Year...........14 All-Ivy Teams ................................................15-23 All-Americans .................................................24-26 Academic All-Americans .....................................26 In the MLS Drafts ................................................27 * - Last updated on June 2017. If you have updates or possible edits to the men’s soccer records book, please email [email protected] 17 1 18 Ivy League Records Book MEN’S SOCCER All-Time Champions YEAR CHAMPION(S) IVY CHAMPIONS 1955 Harvard 1995 Cornell Total Outright First Last Penn Brown Champs Champs Champ Champ 1956 Yale 1996 Harvard Brown 20 12 1963 2011 1957 Princeton 1997 Brown Columbia 10 7 1978 2016 Cornell 4 2 1975 2012 1958 Harvard 1998 Brown Dartmouth 12 4 1964 2016 1959 Harvard 1999 Princeton Harvard 13 9 1955 2009 1960 Princeton 2000 Brown Penn 8 3 1955 2013 Princeton 8 4 1957 2014 1961 Harvard 2001 Brown Yale 5 4 1956 2005 1962 Penn Princeton Harvard 2002 Penn 1963 Brown Dartmouth Harvard 2003 Brown 1964 Brown 2004 Dartmouth Dartmouth 2005 Brown 1965 -

2017-18 Panini Nobility Soccer Cards Checklist

Cardset # Player Team Seq # Player Team Note Crescent Signatures 28 Abby Wambach United States Alessandro Del Piero Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 28 Abby Wambach United States 49 Alessandro Nesta Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 28 Abby Wambach United States 20 Andriy Shevchenko Ukraine DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 28 Abby Wambach United States 10 Brad Friedel United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 28 Abby Wambach United States 1 Carles Puyol Spain DEBUT Crescent Signatures 16 Alan Shearer England Carlos Gamarra Paraguay DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 16 Alan Shearer England 49 Claudio Reyna United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 16 Alan Shearer England 20 Eric Cantona France DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 16 Alan Shearer England 10 Freddie Ljungberg Sweden DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 16 Alan Shearer England 1 Gabriel Batistuta Argentina DEBUT Iconic Signatures 27 Alan Shearer England 35 Gary Neville England DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 27 Alan Shearer England 20 Karl-Heinz Rummenigge Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 27 Alan Shearer England 10 Marc Overmars Netherlands DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 27 Alan Shearer England 1 Mauro Tassotti Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures 35 Aldo Serena Italy 175 Mehmet Scholl Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 35 Aldo Serena Italy 20 Paolo Maldini Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 35 Aldo Serena Italy 10 Patrick Vieira France DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 35 Aldo Serena Italy 1 Paul Scholes England DEBUT Crescent Signatures 12 Aleksandr Mostovoi -

MLS: Five Things to Watch Post All-Star Game

MLS: Five Things to Watch Post All-Star Game Author : Steven Jotterand Tonight the soccer world turns to Chicago, Illinois. Well, sort of. MLS will field their best against the epic Real Madrid in a glorified exhibition match. This All-Star game signals a transition to the second half of the season. Clubs will begin to turn up the heat as the hunt for the Cup begins. Here are five things to look out for post the All-Star game: LA Galaxy & Orlando City’s Push: In 2016, the Seattle Sounders lost 12 of their first 20 games. Two days after their 12th loss, they sacked Sigi Schmid and hired Brian Schmetzer as interim. One day after naming their new man in charge, Seattle made a splash and signed creative Uruguayan midfielder Nicklas Lodeiro as a Designated Player. A club that was trending nowhere, changed their fortunes around. Within weeks, they were one of the most feared clubs in the league. The Sounders also went on to lift the MLS Cup. 1 / 3 The Galaxy are pretty much exactly in the same position heading into the All-Star Game as Sounders was in 2016. Having lost ten of the first 21 games and sitting in ninth in a weaker Western Conference, the board sacked Curt Onalfo, hired Sigi Schmid, and signed Mexican international attacking midfielder Jonathan dos Santos from Villarreal as a Designated player. Related Post: Orlando City SC: Upstart Lions Stalking and Devouring Their MLS Prey Struggling Orlando City did not sack their manager, but just pulled off the largest trades in MLS history for Dom Dwyer. -

Women's Soccer Awards

WOMEN’S SOCCER AWARDS All-America Teams 2 National Award Winners 15 ALL-AMERICA TEAMS NOTE: From 1980-85, the National D–Karen Gollwitzer, SUNY Cortland D–Karen Nance, UC Santa Barbara M–Amanda Cromwell, Virginia Soccer Coaches Association of D–Lori Stukes, Massachusetts D–Kim Prutting, Connecticut M–Linda Dorn, UC Santa Barbara America (NSCAA) selected one F–Pam Baughman, George Mason D–Shelley Separovich, Colorado Col. M–Jill Rutten, NC State All-America team that combined all F–Bettina Bernardi, Texas A&M D–Carla Werden, North Carolina F–Brandi Chastain, Santa Clara three divisions. Starting in 1986, Division III selected its own team, F–Moira Buckley, Connecticut F–Michelle Akers, UCF F–Lisa Cole, SMU but Divisions I and II continued to F–Stacey Flionis, Massachusetts F–Joy Biefeld, California F–Mia Hamm, North Carolina select one team. Starting in 1988, F–Lisa Gmitter, George Mason F–Shannon Higgins, North Carolina F–Kristine Lilly, North Carolina all three divisions selected their 1984 F–April Kater, Massachusetts F–April Kater, Massachusetts own teams. Soccer America started F–Jennifer Smith, Cornell NSCAA 1991 selecting a team in 1988, which SOCCER AMERICA included all divisions. Beginning in G–Monica Hall, UC Santa Barbara NSCAA 1990, the team was selected from D–Suzy Cobb, North Carolina D–Lisa Bray, William Smith G–Heather Taggart, Wisconsin only Division I schools. NSCAA and D–Leslie Gallimore, California D–Linda Hamilton, NC State D–Holly Hellmuth, Massachusetts was rebranded as United Soccer D–Liza Grant, Colorado Col. D–Lori Henry, North Carolina M–Cathleen Cambria, Connecticut Coaches in 2017. -

Pittsburgh Riverhounds Sc (4-2-7) at Columbus Crew Sc (5-9-2)

Riverhounds SC Communications Anthony Picardi, Director of Communications E: [email protected] | O: (412) 325-7229 | C: (412) 952-5789 PITTSBURGH RIVERHOUNDS SC (4-2-7) 2019 SCHEDULE & RECORD AT COLUMBUS CREW SC (5-9-2) Overall Record: 4-2-7 Home: 3-0-4 • Away: 1-2-3 Tuesday, June 11, 2019 >> 7 p.m. ET >> MAPFRE Stadium >> Columbus, OH MARCH TALE OF THE TAPE Sat. 16 @Tampa Bay Rowdies CW L, 0-2 USOC ROUND 4 - QUICK HITTERS Sat. 23 @Swope Park Rangers CW T, 2-2 • Riverhounds SC advances to the fourth round of the Lamar Sat. 30 @Bethlehem Steel FC CW T, 2-2 Hunt U.S. Open Cup, where it will meet Columbus Crew APRIL SC of MLS. Crew SC, as well as other MLS teams, enter the Sat. 6 @Louisville City FC CW W, 1-0 tournament in the fourth round of action. Sat. 13 HARTFORD ATHLETIC ESPN+ W, 3-1 • This will mark the first time Pittsburgh and Columbus will meet Sat. 20 SAINT LOUIS FC ESPN+ T, 0-0 in the Open Cup. Sat. 27 NASHVILLE SC ESPN+ T, 2-2 • In the third round of Open Cup play, Pittsburgh defeated Indy PITTSBURGH COLUMBUS Eleven 1-0 at Highmark Stadium. MidfielderKenardo Forbes, MAY Sat. 4 @Charleston Battery CW T, 2-2 4-2-7 Overall Record 5-9-2 a second-half substitute, led the way with a goal in the 85th Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup Round 2* USL Championship League MLS minute. Bob Lilley Head Coach Caleb Porter Tue. -

Rutgers Men's Soccer Record Book

Q U I C K FA C T S RUTGERS MEN’S SOCCER RECORD BOOK 1 1 RUTGERS MEN’S SOCCER University Information 2017 Information Get Connected Location ............. New Brunswick, N.J. 2016 Overall Record ...............1-14-2 Twitter: @RUMensSoccer • @RUAthletics Founded .......................................1766 2016 Big Ten Record ..........0-6-2/9th Enrollment ................................65,000 2016 Post Season ........................N/A Instagram @RUMensSoccer • @RUAthletics President ................... Robert L. Barchi Starters Returning .............................6 Facebook Facebook.com/RutgersMensSoccer Director of Athletics ...........Pat Hobbs Starters Lost ........................................5 Nickname ....................Scarlet Knights Letterwinners Returning .............. 13 Snapchat RUAthletics Color ..........................................Scarlet Letterwinners Lost ............................5 Conference ..............................Big Ten Newcomers ..................................... 14 Mascot ...........................Scarlet Knight Ticket Office ..............866-445-GORU Website ................scarletknights.com Coaching Information 2017 Schedule Head Coach ...................Dan Donigan Date Opponent Times Team History .................................... Connecticut ‘93 Aug. 13 UCONN # .............. 1 p.m. First Year of Soccer ....................1938 Overall Record ..................................... Aug. 16 @ Monmouth # ......... 7 p.m. All-Time Record ............ 577-443-119 ......................