Sumerian Peasant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artist: Period/Style: Patron: Material/Technique: Form

TITLE: Apollo 11 Stones LOCATION: Namibia DATE: 25,500-25,300 BCE ARTIST: PERIOD/STYLE: Mesolithic Stone Age PATRON: MATERIAL/TECHNIQUE: FORM: The Apollo 11 stones are a collection of grey-brown quartzite slabs that feature drawings of animals painted with charcoal, clay, and kaolin FUNCTION: These slabs may have had a more social function. CONTENT: Drawings of animals that could be found in nature. On the cleavage face of what was once a complete slab, an unidentified animal form was drawn resembling a feline in appearance but with human hind legs that were probably added later. Barely visible on the head of the animal are two slightly-curved horns likely belonging to an Oryx, a large grazing antelope; on the animal’s underbelly, possibly the sexual organ of a bovid. CONTEXT: Inside the cave, above and below the layer where the Apollo 11 cave stones were found, archaeologists unearthed a sequence of cultural layers representing over 100,000 years of human occupation. In these layers stone artifacts, typical of the Middle Stone Age period—such as blades, pointed flakes, and scraper—were found in raw materials not native to the region, signaling stone tool technology transported over long distances.Among the remnants of hearths, ostrich eggshell fragments bearing traces of red color were also found—either remnants of ornamental painting or evidence that the eggshells were used as containers for pigment. Approximately 25,000 years ago, in a rock shelter in the Huns Mountains of Namibia on the southwest coast of Africa (today part of the Ai-Ais Richtersveld Transfrontier Park), an animal was drawn in charcoal on a hand-sized slab of stone. -

Lecture 27 Sasanian Empire

4/12/2012 Lecture 27 Sasanian Empire HIST 213 Spring 2012 Sasanian Empire (224-651 CE) Successors of the Achaemenids 224 CE Ardashir I • a descendant of Sasan – gave his name to the new Sasanian dynasty, • defeated the Parthians • The Sasanians saw themselves as the successors of the Achaemenid Persians. 1 4/12/2012 Shapur I (r. 241–72 CE) • One of the most energetic and able Sasanian rulers • the central government was strengthened • the coinage was reformed • Zoroastrianism was made the state religion • The expansion of Sasanian power in the west brought conflict with Rome Shapur I the Conqueror • conquers Bactria and Kushan in east • led several campaigns against Rome in west Penetrating deep into Eastern-Roman territory • conquered Antiochia (253 or 256) Defeated the Roman emperors: • Gordian III (238–244) • Philip the Arab (244–249) • Valerian (253–260) – 259 Valerian taken into captivity after the Battle of Edessa – disgrace for the Romans • Shapur I celebrated his victory by carving the impressive rock reliefs in Naqsh-e Rostam. Rome defeated in battle Relief of Shapur I at Naqsh-e Rostam, showing the two defeated Roman Emperors, Valerian and Philip the Arab 2 4/12/2012 Terry Jones, Barbarians (BBC 2006) clip 1=9:00 to end clip 2 start - … • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t_WqUbp RChU&feature=related • http://www.youtube.com/watch?NR=1&featu re=endscreen&v=QxS6V3lc6vM Shapur I Religiously Tolerant Intensive development plans • founded many cities, some settled in part by Roman emigrants. – included Christians who could exercise their faith freely under Sasanian rule • Shapur I particularly favored Manichaeism – He protected Mani and sent many Manichaean missionaries abroad • Shapur I befriends Babylonian rabbi Shmuel – This friendship was advantageous for the Jewish community and gave them a respite from the oppressive laws enacted against them. -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Money, History and Energy Accounting Essay Author: Skip Sievert June 2008 Open Source Information

Some Historic aspects of money... Money, History and Energy accounting Essay author: Skip Sievert June 2008 open source information. The Technocracy Technate design uses Energy accounting as the viable alternative to the current Price System. Energy Accounting- Fezer. The Emergence of money The use of barter like methods may date back to at least 100,000 years ago. To organize production and to distribute goods and services among their populations, pre- market economies relied on tradition, top-down command, or community cooperation. Relations of reciprocity and/or redistribution substituted for market exchange. Trading in red ochre is attested in Swaziland. Shell jewellery in the form of strung beads also dates back to this period and had the basic attributes needed of commodity money. In cultures where metal working was unknown... shell or ivory jewellery was the most divisible, easily stored and transportable, relatively scarce, and impossible to counterfeit type of object that could be made into a coveted stylized ornament or trading object. It is highly unlikely that there were formal markets in 100,000 B.P. Nevertheless... something akin to our currently used concept of money was useful in frequent transactions of hunter-gatherer cultures, possibly for such things as bride purchase, prostitution, splitting possessions upon death, tribute, obtaining otherwise scarce objects or material, inter-tribal trade in hunting ground rights.. and acquiring handcrafted implements. All of these transactions suffer from some basic problems of barter — they require an improbable coincidence of wants or events. History of the beginnings of our current system Sumerian shell money below. Sumer was a collection of city states around the Lower Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is now southern Iraq. -

EASTERN CENTRAL ASIA the Early History of Central Asia Is Gleaned

CHAPTER FOUR EASTERN CENTRAL ASIA KASHGAR TO KHOTAN I. INTRODUCTION The early history of Central Asia is gleaned primarily from three major sources: the Chinese historical writings, usually governmental records or the diaries of the Bud dhist pilgrims; documents written in Kharosthl-an Indian script also adopted by the Kushans-(and some in an Iranian dialect using technical terms in Sanskrit and Prakrit) that reveal aspects of the local life; and later Muslim, Arab, Persian, and Turkish writings. 1 From these is painstakingly emerging a tentative history that pro vides a framework, admittedly still fragmentary, for beginning to understand this vital area and prime player between China, India, and the West during the period from the 1st to 5th century A.D. Previously, we have encountered the Hsiung-nu, particularly the northern branch, who dominated eastern Central Asia during much of the Han period (206 B.C.-220 A.D.), and the Yiieh-chih, a branch of which migrated from Kansu to northwest India and formed the powerful and influential Kushan empire of ca. lst-3rd century A.D. By ca. mid-3rd century the unified Kushan empire had ceased and the main line of kings from Kani~ka had ended. Another branch (the Eastern Kushans) ruled in Gandhara and the Indus Valley, and the northernpart of the former Kushan em pire came under the rule of Sasanian governors. However, after the death of the Sasanian ruler Shapur II in 379, the so-called Kidarites, named from Kidara, the founder of this "new" or Little Kushan Dynasty (known as the Little Yiieh-chih by the Chinese), appear to have unified the area north and south of the Hindu Kush between around 380-430 (likely before 410). -

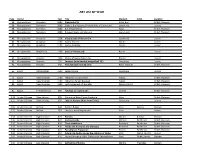

Art List by Year

ART LIST BY YEAR Page Period Year Title Medium Artist Location 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Standard of Ur Inlaid Box British Museum 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Stele of the Vultures (Victory Stele of Eannatum) Limestone Louvre 38 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Bull Headed Harp Harp British Museum 39 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Banquet Scene cylinder seal Lapis Lazoli British Museum 40 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2254 Victory Stele of Narum-Sin Sandstone Louvre 42 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Seated Diorite Louvre 43 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Standing Calcite Louvre 44 Mesopotamia Babylonian 1780 Stele of Hammurabi Basalt Louvre 45 Mesopotamia Assyrian 1350 Statue of Queen Napir-Asu Bronze Louvre 46 Mesopotamia Assyrian 750 Lamassu (man headed winged bull 13') Limestone Louvre 48 Mesopotamia Assyrian 640 Ashurbanipal hunting lions Relief Gypsum British Museum 65 Egypt Old Kingdom 2500 Seated Scribe Limestone Louvre 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun hunting fowl Fresco British Museum 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun funery banquet Fresco British Museum 80 Egypt New Kingdom 1300 Last Judgement of Hunefer Papyrus Scroll British Museum 81 Egypt First Millenium 680 Taharqo as a sphinx (2') Granite British Museum 110 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Corinthian Black Figure Amphora Vase British Museum 111 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Lady of Auxerre (Kore from Crete) Limestone Louvre 121 Ancient Greece Archaic 540 Achilles & Ajax Vase Execias Vatican 122 Ancient Greece Archaic 510 Herakles wrestling Antaios Vase Louvre 133 Ancient Greece High -

Crossroads 360 Virtual Tour Script Edited

Crossroads of Civilization Virtual Tour Script Note: Highlighted text signifies content that is only accessible on the 360 Tour. Welcome to Crossroads of Civilization. We divided this exhibit not by time or culture, but rather by traits that are shared by all civilizations. Watch this video to learn more about the making of Crossroads and its themes. Entrance Crossroads of Civilization: Ancient Worlds of the Near East and Mediterranean Crossroads of Civilization looks at the world's earliest major societies. Beginning more than 5,000 years ago in Egypt and the Near East, the exhibit traces their developments, offshoots, and spread over nearly four millennia. Interactive timelines and a large-scale digital map highlight the ebb and flow of ancient cultures, from Egypt and the earliest Mesopotamian kingdoms of the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, to the vast Persian, Hellenistic, and finally Roman empires, the latter eventually encompassing the entire Mediterranean region. Against this backdrop of momentous historical change, items from the Museum's collections are showcased within broad themes. Popular elements from classic exhibits of former years, such as our Greek hoplite warrior and Egyptian temple model, stand alongside newly created life-size figures, including a recreation of King Tut in his chariot. The latest research on our two Egyptian mummies features forensic reconstructions of the individuals in life. This truly was a "crossroads" of cultural interaction, where Asian, African, and European peoples came together in a massive blending of ideas and technologies. Special thanks to the following for their expertise: ● Dr. Jonathan Elias - Historical and maps research, CT interpretation ● Dr. -

Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq

OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES General Editors Gillian Clark Andrew Louth THE OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES series includes scholarly volumes on the thought and history of the early Christian centuries. Covering a wide range of Greek, Latin, and Oriental sources, the books are of interest to theologians, ancient historians, and specialists in the classical and Jewish worlds. Titles in the series include: Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and the Transformation of Divine Simplicity Andrew Radde-Gallwitz (2009) The Asceticism of Isaac of Nineveh Patrik Hagman (2010) Palladius of Helenopolis The Origenist Advocate Demetrios S. Katos (2011) Origen and Scripture The Contours of the Exegetical Life Peter Martens (2012) Activity and Participation in Late Antique and Early Christian Thought Torstein Theodor Tollefsen (2012) Irenaeus of Lyons and the Theology of the Holy Spirit Anthony Briggman (2012) Apophasis and Pseudonymity in Dionysius the Areopagite “No Longer I” Charles M. Stang (2012) Memory in Augustine’s Theological Anthropology Paige E. Hochschild (2012) Orosius and the Rhetoric of History Peter Van Nuffelen (2012) Drama of the Divine Economy Creator and Creation in Early Christian Theology and Piety Paul M. Blowers (2012) Embodiment and Virtue in Gregory of Nyssa Hans Boersma (2013) The Chronicle of Seert Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq PHILIP WOOD 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries # Philip Wood 2013 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2013 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. -

The British Museum Annual Reports and Accounts 2019

The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 HC 432 The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 9(8) of the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed on 19 November 2020 HC 432 The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 © The British Museum copyright 2020 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as British Museum copyright and the document title specifed. Where third party material has been identifed, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/ofcial-documents. ISBN 978-1-5286-2095-6 CCS0320321972 11/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fbre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Ofce The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 Contents Trustees’ and Accounting Ofcer’s Annual Report 3 Chairman’s Foreword 3 Structure, governance and management 4 Constitution and operating environment 4 Subsidiaries 4 Friends’ organisations 4 Strategic direction and performance against objectives 4 Collections and research 4 Audiences and Engagement 5 Investing -

Downloadable (Ur 2014A)

oi.uchicago.edu i FROM SHERDS TO LANDSCAPES oi.uchicago.edu ii oi.uchicago.edu iii FROM SHERDS TO LANDSCAPES: STUDIES ON THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST IN HONOR OF McGUIRE GIBSON edited by MARK ALTAWEEL and CARRIE HRITZ with contributions by ABBAS ALIZADEH, BURHAN ABD ALRATHA ALRATHI, MARK ALTAWEEL, JAMES A. ARMSTRONG, ROBERT D. BIGGS, MIGUEL CIVIL†, JEAN M. EVANS, HUSSEIN ALI HAMZA, CARRIE HRITZ, ERICA C. D. HUNTER, MURTHADI HASHIM JAFAR, JAAFAR JOTHERI, SUHAM JUWAD KATHEM, LAMYA KHALIDI, KRISTA LEWIS, CARLOTTA MAHER†, AUGUSTA MCMAHON, JOHN C. SANDERS, JASON UR, T. J. WILKINSON†, KAREN L. WILSON, RICHARD L. ZETTLER, and PAUL C. ZIMMERMAN STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION • VOLUME 71 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu iv ISBN (paperback): 978-1-61491-063-3 ISBN (eBook): 978-1-61491-064-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2021936579 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 2021 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2021. Printed in the United States of America Series Editors Charissa Johnson, Steven Townshend, Leslie Schramer, and Thomas G. Urban with the assistance of Rebecca Cain and Emily Smith and the production assistance of Jalissa A. Barnslater-Hauck and Le’Priya White Cover Illustration Drawing: McGuire Gibson, Üçtepe, 1978, by Peggy Sanders Design by Steven Townshend Leaflet Drawings by Peggy Sanders Printed by ENPOINTE, Brooklyn Park, Minnesota, USA This paper meets the requirements of ANSI Z39.48-1984 (Permanence of Paper) ∞ oi.uchicago.edu v TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations ................................................................................. vii Editor’s Note ........................................................................................ ix Introduction. Richard L. -

The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia Emerged out of the Chaos That Engulfed the Assyrian Empire After the Death of the Akka

NAME: DATE: The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia emerged out of the chaos that engulfed the Assyrian Empire after the death of the Akkadian king, Ashurbanipal. The Neo-Babylonian Empire extended across Mesopotamia. At its height, the region ruled by the Neo-Babylonian kings reached north into Anatolia, east into Persia, south into Arabia, and west into the Sinai Peninsula. It encompassed the Fertile Crescent and the Tigris and Euphrates River valleys. New Babylonia was a time of great cultural activity. Art and architecture flourished, particularly under the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, was determined to rebuild the city of Babylonia. His civil engineers built temples, processional roadways, canals, and irrigation works. Nebuchadnezzar II sought to make the city a testament not only to Babylonian greatness, but also to honor the Babylonian gods, including Marduk, chief among the gods. This cultural revival also aimed to glorify Babylonia’s ancient Mesopotamian heritage. During Assyrian rule, Akkadian language had largely been replaced by Aramaic. The Neo-Babylonians sought to revive Akkadian as well as Sumerian-Akkadian cuneiform. Though Aramaic remained common in spoken usage, Akkadian regained its status as the official language for politics and religious as well as among the arts. The Sumerian-Akkadian language, cuneiform script and artwork were resurrected, preserved, and adapted to contemporary uses. ©PBS LearningMedia, 2015 All rights reserved. Timeline of the Neo-Babylonian Empire 616 Nabopolassar unites 575 region as Neo- Ishtar Gate 561 Amel-Marduk becomes king. Babylonian Empire and Walls of 559 Nerglissar becomes king. under Babylon built. 556 Labashi-Marduk becomes king. Chaldean Dynasty. -

Representations of Plants on the Warka Vase of Early Mesopotamia

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons University of Pennsylvania Museum of University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Papers Archaeology and Anthropology 2016 Sign and Image: Representations of Plants on the Warka Vase of Early Mesopotamia Naomi F. Miller University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Philip Jones University of Pennsylvania Holly Pittman University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Botany Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation (OVERRIDE) Miller, Naomi F., Philip Jones, and Holly Pittman. 2016. Sign and image: representations of plants on the Warka Vase of early Mesopotamia. Origini 39: 53–73. University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons, Philadelphia. http://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers/2 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers/2 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sign and Image: Representations of Plants on the Warka Vase of Early Mesopotamia Abstract The Warka Vase is an iconic artifact of Mesopotamia. In the absence of rigorous botanical study, the plants depicted on the lowest register are usually thought to be flax and grain. This analysis of the image identified as grain argues that its botanical characteristics, iconographical context and similarity to an archaic sign found in proto-writing demonstrates that it should be identified as a date palm sapling. It confirms the identification of flax. The correct identification of the plants furthers our understanding of possible symbolic continuities spanning the centuries that saw the codification of text as a eprr esentation of natural language.