Horace Sudduth, Queen City Entrepreneur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fort Dearborn INSTRUCTOR NOTE 2 Ask Students to Locate the First Star on the Chicago Flag

MMyy ChicagoCChicagoChhiiccaaggoo Fort Dearborn INSTRUCTOR NOTE 2 Ask students to locate the first star on the Chicago flag. Remind stu- dents that this star represents Fort Dearborn. In 1803, the United States built a fort near what is today the Chicago River. One of the people who lived at the fort was Rebecca Heald, the wife of the captain of Fort Dearborn, Nathaniel Heald. This historical fiction narrative is told in her voice. Prior to reading the narrative, review the following vocabulary words with students. Vocabulary allies—groups of people who fight on the same side during a war cede—to yield or grant, typically by treaty explorers—people who travel for adventure or to discover new things settler—someone who moves to a new area and lives there wealthy—rich merchant—someone who buys and sells things established—started mill—a building where grain is turned into flour trading post—an area where people meet to buy, sell, and trade things port—a place where boats come to load and unload things fort—a trading post protected by soldiers evacuate—leave abandoned—left empty mementos—small objects that are important to a person and remind them of past events extraordinary—special 10 2. My CChicagohicago Narrative grounds, a garden and stables, and even a efore I was married, my name was shop where firearms were made and repaired. Rebecca Wells. As a young girl, I Bknew very little about the area that became Chicago. Little did I know that it would be my future home as a newly mar- ried woman. -

Re-Evaluating “The Fort- Wayne Manuscript” William Wells and the Manners and Customs of the Miami Nation

Re-evaluating “The Fort- Wayne Manuscript” William Wells and the Manners and Customs of the Miami Nation WILLIAM HEATH n April 1882, Hiram W. Beckwith of Danville, Illinois, received an Iunusual package: a handwritten manuscript of twenty-eight pages of foolscap sent to him by S. A. Gibson, superintendent of the Kalamazoo Paper Company. 1 The sheets, which appeared to have been torn from a larger manuscript, were part of a bundle of old paper that had been shipped for pulping from Fort Wayne, Indiana, to the company mills in Michigan. 2 Gibson must have realized that the material was of historical interest when he sent it on to Beckwith, who was known for his research into the frontier history of the Northwest Territory. Indeed, the packet __________________________ William Heath is Professor Emeritus of English at Mount Saint Mary’s University; he presently teaches in the graduate humanities program at Hood College in Frederick, Maryland. He is the author of a book of poems, The Walking Man , and two novels, The Children Bob Moses Led and Blacksnake’s Path: The True Adventures of William Wells . The author is grateful for a fellow - ship at the Newberry Library in Chicago, which led to many of the findings presented in the essay. 1Hiram W. Beckwith (1830-1903) was Abraham Lincoln’s law partner from 1856 to 1861 and a close personal friend. He edited several volumes in the Fergus’ Historical Series and served from 1897 to 1902 as president of the Historical Society of Illinois. 2The bundle of papers was “The Fort-Wayne Manuscript,” box 197, Indian Documents, 1811- 1812, Chicago History Museum. -

The Next Dance For

The next dance for the anse A project to renovate the historic Manse Hotel whileM preserving quality affordable housing for low-income seniors in Walnut Hills, a community undergoing significant revitalization. A collaborative partnership led by: A Visionary in Affordable Housing In the early 1900s, Cincinnati millionaire Jacob G. Schmidlapp was deeply concerned with our city’s housing problem. He devoted himself to developing dignified affordable tenements for low-income families, particularly African Americans. Referring to his approach as “Philanthropy Plus 5%,” he encouraged others to invest to “do good” while receiving a modest return on investment. He concentrated his efforts in the community of Walnut Hills where he installed bathrooms in each apartment, ensured ample air circulation through strategically placed windows, created community rooms and encouraged civic and social gatherings. These were not housing requirements of the times, but what Schmidlapp considered to be a moral standard. Safe, comfortable senior communities by Episcopal Retirement Services A Vision of Our Own Nearly a century later, leaders at Episcopal Retirement Services reflected on our own moral standards. Like Jacob Schmidlapp, the leadership within ERS and its board realized that quality affordable housing for low-income seniors was woefully lacking. To expand ERS’ mission of serving older adults in a person-centered, innovative and spiritually based way, ERS’ board devised an aggressive plan to grow Affordable Living by ERS. At the heart of Affordable Living by ERS is an array of services, well-being and enrichment programs, home-like community spaces with furnishings, fitness equipment, and safety and security installations. These services and amenities empower older adults to remain living independently as long as possible, ideally until the end of their lives. -

S3439 William Wells

Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters Pension Application of William Wells: S 3439 [f26VA] Transcribed by Judith F. Russell 1/11/11 William Wells 1753 - 1833 Revolutionary Pension Application S 3494 State of Tennessee Giles County Before William B. Pepper, Esq. On the 6th day of October in A.D. 1832 personally appeared before the said William B. Pepper, Esq. A justice of the peace for said county William Wells a resident of said county and state aged 78 years since December last, who is unable to appear in Court by reason of his bodily infirmities, and who being first duly sworn according to law, doth on his oath make the following declaration in order to obtain the benefit of the Act of Congress, passed June 7th, 1832. That he entered the service of the United States and under the following named officers and served as herein stated. When he entered the United States Service he resided in the County of Prince George in the state of Virginia. He enlisted in the regular service for the term of 3 years. He went into said service under the command of Captain Thomas Ruffin and Lieut. Halley Every (Ewing?) in General Muhlenburg’s Brigade. The troops to which applicant was attached rendezvoued at Williamsburgh in the state of Virginia. He thinks they marched from thence to the White Plains in the state of New York, but of this applicant is not positive, he being very old and his memory treacherous. He thinks the headquarters of his associated troops were sometime at While Plains. -

Creating a Frontier War: Harrison, Prophetstown, and the War of 1812. Patrick Bottiger, Ph.D., [email protected] Most Scholars

1 Creating a Frontier War: Harrison, Prophetstown, and the War of 1812. Patrick Bottiger, Ph.D., [email protected] Most scholars would agree that the frontier was a violent place. But only recently have academics begun to examine the extent to which frontier settlers used violence as a way to empower themselves and to protect their interests. Moreover, when historians do talk about violence, they typically frame it as the by-product of American nationalism and expansion. For them, violence is the logical result of the American nation state’s dispossessing American Indians of their lands. Perhaps one of the most striking representations of the violent transition from frontier to nation state is that of Indiana Territory’s contested spaces. While many scholars see this violence as the logical conclusion to Anglo-American expansionist aims, I argue that marginalized French, Miamis, and even American communities created a frontier atmosphere conducive to violence (such as that at the Battle of Tippecanoe) as a means to empower their own agendas. Harrison found himself backed into a corner created by the self-serving interests of Miami, French, and American factions, but also Harrison own efforts to save his job. The question today is not if Harrison took command, but why he did so. The arrival of the Shawnee Prophet and his band of nativists forced the French and Miamis to take overt action against Prophetstown. Furious that the Shawnee Prophet established his community in the heart of Miami territory, the French and Miamis quickly identified the Prophet as a threat to regional stability. -

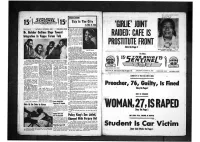

W0man,27, Is Raped W

"~T~~^ OHIO STATE ssUSEUal LI3RARI 15TH t Hldll ST." CHICAGO DATELINE C0LUU3SJ3, OHIO THE OHIO _ "Jf:?^mmmjesammmms ' 5 EN' This Is The City By WHA H. WOO -GIRUE' JOINT COLUMBUS. OUK J**VB VOL. 6 No. IS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 9, 19S4 ailed the Campus" Instead of Its reg ular title. I've been playing it real close to home base this Dr. Butcher Outlines Steps Toward firsl week of classes so my hori zon's limited by the grey Cojhi building; University ot RAIDED; CAFE IS Integration in Kappa Forum Talk sudden 'ultach- PROSTITUTE FRONT ilp! WP Story On Page 3 RUTH BARBEE McCLOUD . allied that bat the fashion "Madam." Storr On Paa. 3. world going ln two directions at once. The rage here Is the BU Look. The sdudents go to great pains and destruction to acquire the "beat up" look. Keen tu, tbe point of punching holes In cashmere sweaters, putting side (Hy Edition slits in jackets that don't have them and sewing ap sills (with purple thread of coarse) In jackets that do bsve litem. Any clothing that looks new Is strictly taboo. Apparel most It just isn't stylish. Tfae place to shop for a really ~ "at the nearest K K IinmrdiiilrlT before opening Sunday of the current fall forum series sponsored by Columbu*. c.i.s*|iifr ef Kapp4 Alpha Psi fraternity, participants scan « program. From left: A. 3. Allen, A BY-PRODUCT AND BOSOM PAL OF Uie BU Look is the executive secretary, Pittsburgh Urban League, l>r. Margaret J. Butrher. principal speaker. -

Reclaiming Revolution William Wells Brown’S Irreducible Haitian Heroes

367-383 228172 Fagan (D) 26/11/07 16:33 Page 367 Article Comparative American Studies An International Journal Copyright © 2007 W. S. Maney & Son Ltd Vol 5(4): 367–383 DOI: 10.1179/147757007X228172 http://www.maney.co.uk Reclaiming revolution William Wells Brown’s irreducible Haitian heroes Ben Fagan University of Virginia, USA Abstract This article examines black abolitionist William Wells Brown’s 1854 lecture St. Domingo: Its Revolutions and its Patriots, juxtaposing Brown’s history of the Haitian Revolution against those printed in publica- tions such as the American DeBow’s Review and the British Anti-Slavery Reporter. The staggered, often contradictory nature of the multiple insurrec- tions and uprisings occurring in Haiti complement Brown’s own interest in fragmented narratives, and allow him to offer a model for black revolution- ary activity contained not in a singular moment or figure, but instead spread across multiple revolutions and revolutionaries. Following Brown’s logic opens up the possibility of developing an international revolutionary contin- uum deeply dependent upon black liberatory goals. A host of events could subsequently re-emerge as part of such a continuum, including but certainly not limited to the American Revolution, the Haitian Revolution, and an inter- nationally inflected American Civil War. Keywords abolitionism ● Haiti ● history ● revolution ● Toussaint L’Ouverture On 16 May 1854, the African-American abolitionist, William Wells Brown rose to give a lecture at London’s elite Metropolitan Athenaeum. Brown had been in England for five years, devoting a substantial amount of that time to speaking engagements across the British Isles. Black abolitionists in England traditionally recounted the horrors of American slavery, with special attention being paid to personal experience. -

The Role of the Kentucky Mounted Militia in the Indian Wars from 1768 to 1841

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 Conquerors or cowards: the role of the Kentucky mounted militia in the Indian wars from 1768 to 1841. Joel Anderson University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Joel, "Conquerors or cowards: the role of the Kentucky mounted militia in the Indian wars from 1768 to 1841." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3083. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3083 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONQUERORS OR COWARDS: THE ROLE OF THE KENTUCKY MOUNTED MILITIA IN THE INDIAN WARS FROM 1768 TO 1841 By Joel Anderson B.S. Indiana University Southeast, 2011 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Art in History Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2018 CONQUERORS OR COWARDS: THE ROLE OF THE KENTUCKY MOUNTED MILITIA IN THE INDIAN WARS FROM 1768 to 1813 By Joel Anderson B.A., Indiana University Southeast, 2011 A Thesis Approved on November 6, 2018 by the following Thesis Committee: ______________________________________ Dr. -

William Wells and the Struggle for the Old Northwest 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WILLIAM WELLS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR THE OLD NORTHWEST 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Heath | 9780806157504 | | | | | William Wells and the Struggle for the Old Northwest 1st edition PDF Book Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Despite the treaty, which ceded the Northwest Territory to the United States, the British kept forts there and continued policies that supported the Native Americans. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. Odawa and Potawatomi under Little Otter and Egushawa occupied the center and initiated the attack against the Legion's scouts. He also brought a dire warning that a force of over warriors was ready to attack Fort Jefferson and the Legion of the United States , then camped near Fort Washington. Clair's Defeat which he had fought in and located several abandoned U. Co-operation among the Native American tribes in the Western Confederacy had gone back to the French colonial era. During the course of the American Revolutionary War, United States forces captured outposts in the lower areas of the territory, but British forces maintained control of Fort Lernoult Detroit. Get your order now, pay in four fortnightly payments. Villages and individual warriors and chiefs decided on participation in the war. Wells was shot and killed by the Potowatamis. Because he came to question treaties he had helped bring about, and cautioned the Indians about their harmful effects, he was distrusted by Americans. The treaty and the Wabash tribes were celebrated in Philadelphia, and Henry Knox suggested that the confederacy had been weakened by warriors. More information about this seller Contact this seller. In addition, the Chickamauga Lower Town Cherokee leader, Dragging Canoe , sent a contingent of warriors for a specific action. -

William Wells: Frontier Scout and Indian Agent

William Wells: Frontier Scout and Indian Agent Paul A. Hutton” William Wells occupies an important place in the history of Indian-white relations in the Old Northwest. First as a Miami warrior and then as an army scout he participated in many of the northwestern frontier’s great battles; later as an Indian agent he held a critical position in the implementation of the United States’ early Indian policy. He was what was known along the frontier as a “white Indian,” a unique type often found along the ever-changing border that marked the bound- ary of the Indian country. As such, he was the product of two very different cultures, and throughout his forty-two years of life he swayed back and forth between them-never sure to which he truly belonged. Such indecision doomed him, for he could never be fully accepted by either society. When at last he perished in battle, it would be in defense of whites, but he would be dressed and painted as an Indian. Such was the strange paradox of his life. Born near Jacob’s Creek, Pennsylvania, in 1770, Wells was only nine when his family migrated down the Ohio River on flatboats in company with the families of William Pope and William Oldham to settle on the Beargrass, near what is now Louisville, Kentucky. His older brothers, Samuel and Hayden, had explored the region in 1775 and reported its richness to their father, Captain Samuel Wells, Sr., late of the Revolution- my army. No sooner had the old soldier settled his family in a fortified enclosure called Wells Station (three and one half miles north of present Shelbyville, Kentucky) than he was killed in the ambush of Colonel John Floyd’s militiamen near Louisville in 1781. -

Standing Right Here: the Built Environment As a Tool for Historical Inquiry

Standing Right Here: The Built Environment as a Tool for Historical Inquiry A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of History, College of Arts and Sciences by Anne Delano Steinert October 2020 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2015 M.S. Columbia University, 1995 B.A. Goucher College, 1992 Committee Chair: Tracy Teslow, PhD Abstract The built environment is an open archive—a twenty-four-hour museum of the past. The tangible, experiential nature of the urban built environment—streets, valleys, buildings, and bridges—helps historians uncover stories not always accessible in textual sources. The richness of the built environment gives historians opportunities to: invigorate their practice with new tools to uncover the stories of the past, expand the historical record with new understandings, and reach a wider audience with histories that feel relevant and meaningful to a broad range of citizens. This dissertation offers a sampling of material, methods and motivations historians can use to analyze the built environment as a source for their important work. Each of the five chapters of this dissertation uses the built environment to tell a previously unknown piece of Cincinnati’s urban history. The first chapter questions the inconvenient placement of the 1867 Roebling Suspension Bridge and uncovers the story of the ferry owner who recognized the bridge as a threat to his business. Chapter two explores privies, the outdoor toilets now missing from the built environment, and their use as sites for women to terminate pregnancies through abortion and infanticide. -

The House of Yisrael Cincinnati: How Normalized Institutional Violence Can Produce a Culture of Unorthodox Resistance 1963 to 2021

THE HOUSE OF YISRAEL CINCINNATI: HOW NORMALIZED INSTITUTIONAL VIOLENCE CAN PRODUCE A CULTURE OF UNORTHODOX RESISTANCE 1963 TO 2021 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities by SABYL M. WILLIS B.A., Central State University, 2014 2021 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES July 27, 2021 I HERBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Sabyl M. Willis ENTITLED The House of Yisrael Cincinnati: How Normalized Institutionalized Violence Can Produce a Culture of Unorthodox Resistance BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Humanities. Awad Halabi, Ph.D. Thesis Director Valerie Stoker, Ph.D. Director, Master of Humanities Program Committee on Final Examination: Awad Halabi, Ph.D. Marlese Durr, Ph.D. Okia Opolot, Ph.D. Barry Milligan, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Academic Affairs Dean of the Graduate School ABSTRACT Willis, Sabyl M. M. Hum, Department of Humanities, Wright State University, 2021. The House of Yisrael Cincinnati: How Normalized Institutional Violence Can Produce a Culture of Unorthodox Resistance 1963 to 2021. This study examines the racial, socio-economic, and political factors that shaped The House of Yisrael, a Black Nationalist community in Cincinnati, Ohio. The members of this community structure their lives following the Black Hebrew Israelite ideology sharing the core beliefs that Black people are the "true" descendants of the ancient Israelites of the biblical narrative. Therefore, as Israelites, Black people should follow the Torah as a guideline for daily life. Because they are the "chosen people," God will judge those who have oppressed them.