THEORETICAL BEHAVIORISM John Staddon Duke University “Isms”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Behavioural Psychology on Consumer Psychology and Marketing

This is a repository copy of The influence of behavioural psychology on consumer psychology and marketing. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94148/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Wells, V.K. (2014) The influence of behavioural psychology on consumer psychology and marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 30 (11-12). pp. 1119-1158. ISSN 0267-257X https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2014.929161 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Behavioural psychology, marketing and consumer behaviour: A literature review and future research agenda Victoria K. Wells Durham University Business School, Durham University, UK Contact Details: Dr Victoria Wells, Senior Lecturer in Marketing, Durham University Business School, Wolfson Building, Queens Campus, University Boulevard, Thornaby, Stockton on Tees, TS17 6BH t: +44 (0) 191 3345099, e: [email protected] Biography: Victoria Wells is Senior Lecturer in Marketing at Durham University Business School and Mid-Career Fellow at the Durham Energy Institute (DEI). -

Chickens Play to the Crowd

Chiandetti, Cinzia (2018) Chickens play to the crowd. Animal Sentience 17(13) DOI: 10.51291/2377-7478.1296 This article has appeared in the journal Animal Sentience, a peer-reviewed journal on animal cognition and feeling. It has been made open access, free for all, by WellBeing International and deposited in the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Animal Sentience 2018.102: Chiandetti on Marino on Thinking Chickens Chickens play to the crowd Commentary on Marino on Thinking Chickens Cinzia Chiandetti Department of Life Sciences University of Trieste Abstract: The time was ripe for Marino’s review of chickens’ cognitive capacities. The research community, apart from expressing gratitude for Marino’s work, should now use it to increase public awareness of chickens’ abilities. People’s views on many animals are ill-informed. Scientists need to communicate and engage with the public about the relevance and societal implications of their findings. Cinzia Chiandetti, assistant professor in Cognitive Neuroscience and Animal Cognition at the University of Trieste, Italy, and Head of the Laboratory of Animal Cognition, investigates the biological roots of musical preferences, the development of cerebral lateralization and habituation. Awarded the L'Oréal prize for Women in Science, she is active in disseminating the scientific achievements of the field to the broad public. sites.google.com/site/laboratoryanimalcognition/ I remember reading the story of Keller and Marian Breland, who, under Skinner’s supervision, studied the operant principles for training rats and pigeons, applying them to many other species in the fields of advertising and entertainment. -

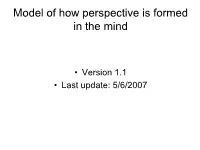

Model of How Perspective Is Formed in the Mind

Model of how perspective is formed in the mind • Version 1.1 • Last update: 5/6/2007 Simple model of information processing, perception generation, and behavior Feedback can distort data from input Information channels Data Emotional Filter Cognitive Filter Input Constructed External Impact Analysis Channels Perspective information “How do I feel about it?” “What do I think about it? ” “How will it affect Sight Perceived Reality i.e. news, ETL Process ETL Process me?” Hearing environment, Take what feels good, Take what seems good, Touch Word View etc. reject the rest or flag reject the rest or flag Smell as undesirable. as undesirable. Taste Modeling of Results Action possible behaviors Motivation Impact on Behavior “What might I do?” Anticipation of Gain world around Or you “I do something” Options are constrained Fear of loss by emotional and cognitive filters i.e bounded by belief system Behavior Perspective feedback feedback World View Conditioning feedback Knowledge Emotional Response Information Information Experience Experience Filtered by perspective and emotional response conditioning which creates “perception” Data Data Data Data Data Data Data Data Data Newspapers Television Movies Radio Computers Inter-person conversations Educational and interactions Magazines Books Data sources system Internet Data comes from personal experience, and “information” sources. Note that media is designed to feed preconceived “information” directly into the consciousness of the populace. This bypasses most of the processing, gathering, manipulating and organizing of data and hijacks the knowledge of the receiver. In other words, the data is taken out of context or in a pre selected context. If the individual is not aware of this model and does not understand the process of gathering, manipulating and organizing data in a way that adds to the knowledge of the receiver, then the “information” upon which their “knowledge” is based can enter their consciousness without the individual being aware of it or what impact it has on their ability to think. -

On Choice and the Law of Effect

2014, 27(4), 569-584 Stanley J. Weiss, Editor Special Issue Peer-reviewed On Choice and the Law of Effect J. E. R. Staddon Duke University, USA Cumulative records, which show individual responses in real time, are a natural but neglected starting point for understanding the dynamics of operant behavior. To understand the processes that underlie molar laws like matching, it is also helpful to look at choice behavior in situations such as concurrent random ratio that lack the stabilizing feedback intrinsic to concurrent variable-interval schedules. The paper identifies some basic, non-temporal properties of operant learning: Post-reinforcement pulses at the beginning of FI learning, regression, faster reversal learning after shorter periods, and choice distribution on identical random ratios at different absolute ratio values. These properties suggest that any operant-learning model must include silent responses, competing to become the active response, and response strengths that reflect more than immediate past history of reinforcement. The cumulative-effects model is one that satisfies these conditions. Two months before his engagement to his cousin Emma Wedgwood, Charles Darwin wrote copious notes listing the pros and cons of marriage. This is typical human choice behavior, though perhaps more conscious and systematic than most. No one would imagine that animals choose like this. But folk psychology often slips in unannounced. In his famous matching-law experiment, to make his procedure work Richard Herrnstein added what is called a changeover delay (COD): neither response could be rewarded for a second or two after each change from one response to the other. The reason was to prevent a third response: switching. -

PSYCO 282: Operant Conditioning Worksheet

PSYCO 282 Behaviour Modification Operant Conditioning Worksheet Operant Conditioning Examples For each example below, decide whether the situation describes positive reinforcement (PR), negative reinforcement (NR), positive punishment (PP), or negative punishment (NP). Note: the examples are randomly ordered, and there are not equal numbers of each form of operant conditioning. Question Set #1 ___ 1. Johnny puts his quarter in the vending machine and gets a piece of candy. ___ 2. I put on sunscreen to avoid a sunburn. ___ 3. You stick your hand in a flame and you get a painful burn. ___ 4. Bobby fights with his sister and does not get to watch TV that night. ___ 5. A child misbehaves and gets a spanking. ___ 6. You come to work late regularly and you get demoted. ___ 7. You take an aspirin to eliminate a headache. ___ 8. You walk the dog to avoid having dog poop in the house. ___ 9. Nathan tells a good joke and his friends all laugh. ___ 10. You climb on a railing of a balcony and fall. ___ 11. Julie stays out past her curfew and now does not get to use the car for a week. ___ 12. Robert goes to work every day and gets a paycheck. ___ 13. Sue wears a bike helmet to avoid a head injury. ___ 14. Tim thinks he is sneaky and tries to text in class. He is caught and given a long, boring book to read. ___ 15. Emma smokes in school and gets hall privileges taken away. ___ 16. -

Attitude and Behavior Change

MCAT-3200020 C06 November 19, 2015 11:6 CHAPTER 6 Attitude and Behavior Change Read This Chapter to Learn About ➤ Associative Learning ➤ Observational Learning ➤ Theories of Attitudes and Behavior Change ASSOCIATIVE LEARNING Associative learning is a specific type of learning. In this type of learning the individual learns to “associate” or pair a specific stimulus with a specific response based on the environment around him or her. This association is not necessarily a conscious process and can include involuntary learned responses (e.g., children in a classroom becoming restless at 2:55 p.m. on a Friday before the 3 p.m. bell). This category of learning includes classical conditioning and operant conditioning. Classical Conditioning Classical conditioning is one of the first associative learning methods that behavioral researchers understood. Classical conditioning has now been shown to occur across both psychological and physiological processes. Classical conditioning is a form of learning in which a response originally caused by one stimulus is also evoked by a second, unassociated stimulus. The Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov and his dogs are most famously associated with this type of conditioning. Pavlov noticed that as the dogs’ dinnertime approached (unconditioned stimulus,orUCS), they began to 91 MCAT-3200020 C06 November 19, 2015 11:6 92 UNIT II: salivate (unconditioned response,orUCR). He found this unusual because the dogs Behavior had not eaten anything, so there was no physiological reason for the increased saliva- tion before the dinner was actually served. Pavlov then experimented with ringing a bell (neutral stimulus) before feeding his dogs. As a result, the dogs began to associate the (previously neutral) bell sound with food and would salivate upon hearing the bell. -

Psycholinguistic Research Methods 251

Psycholinguistic Research Methods 251 See also: Deixis and Anaphora: Pragmatic Approaches; Freud S (1915). ‘Die Verdra¨ngung.’ In Gesammelte Werke Jakobson, Roman (1896–1982); Lacan, Jacques (1901– X. Frankfurt am Main: Imago. 1940–1952. 1981); Metaphor: Psychological Aspects; Metonymy; Lacan J (1955–1956). Les Psychoses. Paris: Seuil, 1981. Rhetoric, Classical. Lacan J (1957). ‘L’instance de la lettre dans l’inconscient ou la raison depuis Freud.’ In E´ crits. Paris: Seuil, 1966. Lacan J (1957–1958). Les formations de l’inconscient. Bibliography Paris: Seuil, 1998. Lacan J (1959). ‘D’une question pre´liminaire a` tout traite- Freud S (1900). ‘Die Traumdeutung.’ In Gesammelte werke ment possible de la psychose.’ In E´ crits. Paris: Seuil, II-III. Frankfurt am Main: Imago. 1940–1952. 1966. Freud S (1901). ‘Zur Psychopathologie des Alltagslebens.’ Lacan J (1964). Les quatre concepts fondamentaux de la In Gesammelte werke IV. Frankfurt am Main: Imago. psychanalyse. Paris: Seuil, 1973. 1940–1952. Lacan J (1969–1970). L’envers de la psychanalyse. Paris: Freud S (1905). ‘Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbe- Seuil, 1991. wussten.’ In Gesammelte Werke, VI. Frankfurt am Main: Imago. 1940–1952. Psycholinguistic Research Methods S Garrod, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK This usually involves taking the average of the values ß 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. of the dependent variable (response latencies) for each value of the independent variable (each list of words acquired at different ages) and establishing Psycholinguistics aims to uncover the mental repre- whether the differences associated with the different sentations and processes through which people pro- values of the independent variable are statistically duce and understand language, and it uses a wide reliable. -

Operant Conditioning

Psyc 390 – Psychology of Learning Operant Conditioning In CC, the focus is on the two stimuli. In Instrumental Conditioning, the focus is on Operant Conditioning the S and how it affects the response. In Operant co nditio ning, what fo llo ws the response is the most important. Psychology 390 That is, the consequent stimulus. Psychology of Learning R – S Steven E. Meier, Ph.D. Thus, you have a Stimulus that causes a Respo nse, which is in turn fo llo wed, by a Listen to the audio lecture while viewing these slides consequent stimulus. 1 2 Psyc 390 – Psychology of Learning Psyc 390 – Psychology of Learning Differences Between Instrumental and Skinner Operant Conditioning Radical Behaviorism • Instrumental • Probably the most important applied • The environment constrains the opportunity psychologist. for reward. • Principles have been used in everything • A specific behavio r is required fo r the reward. • Medicine •Education •Operant • A specific response is required for •Therapy reinforcement. •Business • The frequency of responding determines the amount of reinforcement given. 3 4 Psyc 390 – Psychology of Learning Psyc 390 – Psychology of Learning Distinguished Between Two Types of Responses. Respondents • Respondents • Are elicited by a UCS •Operants • Are innate • Are regulated by the autonomic NS HR, BP, etc. • Are involuntary • Are classically conditioned. 5 6 1 Psyc 390 – Psychology of Learning Psyc 390 – Psychology of Learning Systematically Demonstrated Operants Several Things • Are emitted If something occurs after the response • Are skeletal (consequent stimulus) and the behavior • Are voluntary increases, • Get lots of feedback The procedure is called reinforcement, and the thing that caused the increase is called a reinforcer. -

JEROME SEYMOUR BRUNER COURTESY of RANDALL FOX 1 October 1915

JEROME SEYMOUR BRUNER COURTESY OF RANDALL FOX 1 october 1915 . 5 june 2016 PROCEEDINGS OF THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY VOL. 161, NO. 4, DECEMBER 2017 biographical memoirs s a student of narrative, Jerome (Jerry) Seymour Bruner knew well that one can tell many stories about an individual person, Aevent, and life. Indeed, at the start of his autobiography, Jerry Bruner wrote, “I can find little in [my childhood] that would lead anybody to predict that I would become an intellectual or an academic, even less a psychologist.” And yet, it is appropriate—if not essential—to begin this memoir with the fact that Jerry Bruner was born blind. Only at age 2, after two successful cataract operations (Jerry spoke of “good luck and progress in ophthalmology”) could Jerry see. For the rest of his lengthy and event-filled life, he wore memorably thick corrective lenses. And when he was not peering directly at you—be you an audience of one or of one thousand—he would grasp his glasses firmly in his palm and punctuate his fluent speech with dramatic gestures. As a younger child of an affluent Jewish family living in the suburbs of New York City, Jerry was active, playful, and fun-loving—not partic- ularly intellectual or scholarly. His sister Alice wondered why he was always asking questions; Jerry later quipped that he was “trying out hypotheses.” Freud said that the death of a father is the most important event in a man’s life. Whether or not cognizant of this psychoanalytic pronouncement, Bruner seldom referred to his mother; he devoted much more space in his autobiography and much more time in conver- sation to commemorating his father: “Everything changed, collapsed, after my father died when I was twelve, or so it seemed to me.” And indeed, as he passed through adolescence and into early adulthood, Bruner became a much more serious student, a budding scholar, a wide-ranging intellectual. -

Harry Harlow, John Bowlby and Issues of Separation

Integr Psych Behav (2008) 42:325–335 DOI 10.1007/s12124-008-9071-x INTRODUCTION TO THE SPECIAL ISSUE Loneliness in Infancy: Harry Harlow, John Bowlby and Issues of Separation Frank C. P. van der Horst & René van der Veer Published online: 13 August 2008 # The Author(s) 2008. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract In this contribution, the authors give an overview of the different studies on the effect of separation and deprivation that drew the attention of many in the 1940s and 1950s. Both Harlow and Bowlby were exposed to and influenced by these different studies on the so called ‘hospitalization’ effect. The work of Bakwin, Goldfarb, Spitz, and others is discussed and attention is drawn to films that were used to support new ideas on the effects of maternal deprivation. Keywords Separation . Maternal deprivation . Hospitalization effect . History of psychology. Attachment theory . Harlow. Bowlby From the 1930s through the 1950s clinical and experimental psychology were dominated by ideas from Freud’s psychoanalytic theory and Watson’s behaviorism. Although very different in their approach to the study of (human) behavior, psychoanalysts and behaviorists held common views on the nature of the bond between mother and infant. According to scientists from both disciplines the basis for this relationship was a secondary drive, i.e. the fact that the child valued and loved the mother was because she reduced his or her primary drive for food. The central figure of this special issue, American animal psychologist Harry Harlow (1905–1981), in the 1950s shifted his focus from studies of learning in monkeys (e.g., Harlow and Bromer 1938; Harlow 1949) to a more developmental approach—or in Harlow’s own words a transition “from learning to love” (cf. -

The Vicarious Conditioning of Emotional Responses in Nursery School Children

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 046 540 24 PS 004 408 AUTHOR Venn, Jerry R. TITLE The Vicarious Conditioning of Emotional Responses in Nursery School Children. Final Penort. INSTITUTION Mary Baldwin Coll., Staunton, Va. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DREW) ,Washington, D.C. Bureau of Research. BUREAU NO BR-0 -C-023 PUB DATE 30 Sep 70 GRANT OEG-3-70-0011 (010) NOTE 47p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Conditioned Response, Conditioned Stimulus, *Conditioning, *Emotional Response, Experimental Psychology, *Fear, Films, Models, *Nursery Schools, Operant Conditioning, Tables (Data) IDENTIFIERS *Vicarious Conditioning ABSTRACT To vicariously condition either fear or a positive emotional response, films in which a 5-year-old male model manifested one or the other response were shown to nursery school children. The measure of vicarious conditioning was the children's rate of response to the conditioned stimulus and a controlled stimulus in several operant situations after watching the film. In Experiments 1 and 2, fear responses were vicariously conditioned; after viewing the film, the children rated lower in operant responses to the fear stimulus than to the control stimulus. In Experiments 3 and 4, after viewing a positive film, the children showed a higher rate of operant response to the positive emotional stimulus than to the control stimulus. The experiments show that human operant responses can be affected by both vicarious fear conditioning and vicarious positive emotional conditioning. In all experiments the conditioning effect was short term and easily neutralized. Further research suggested includes: consideration of the age factor; use of live models rather than films; and reduction of experimenter bias, expectations, and generalization by employment of automated apparatus and maximally different test stimuli. -

Not So Fast Mr.Pinker: a Behaviorist Looks at the Blank Slate

Behavior and Social Issues, 12, 75-79 (2002). © Behaviorists for Social Responsibility NOT SO FAST, MR. PINKER: A BEHAVIORIST LOOKS AT THE BLANK SLATE. A REVIEW OF STEVEN PINKER’S THE BLANK SLATE: THE MODERN DENIAL OF HUMAN NATURE 2002, New York: Viking. ISBN 0670031518. 528 pp. $27.95. Stephen Pinker’s latest book, The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature, is getting a lot of press. But Pinker’s claims of human nature hinge in large part on providing evidence of its “modern denial.” Toward that end he singles out behavioral psychology as one of the purveyors of the blank slate position. If the book is judged on how accurately he makes the case, then it doesn’t fare too well. First of all, those interested in how well Pinker succeeds in making his argument for human nature are encouraged to read behavioral biologist Patrick Bateson’s scathing review in Science (September, 2002). Bateson takes Pinker to task for reviving the “wearisome” nature-nurture debate and writes that, “Saloon- bar assertions do not lead to the balanced discussion that should be generated on a topic as important as this one.” Bateson even questions the central assumption of Pinker’s title, namely that human nature is still routinely denied. And he cautions that all examples of behaviors that benefit individuals in the modern world are not necessarily products of evolution. As numerous scientists have pointed out, patterns of behavior that seem to be adaptive may be so because they were selected in our evolutionary history or in individuals’ own lifetimes by learning experiences.