Lifting the Curse: Distribution and Power in Petro-States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rising Sinophobia in Kyrgyzstan: the Role of Political Corruption

RISING SINOPHOBIA IN KYRGYZSTAN: THE ROLE OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY DOĞUKAN BAŞ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF EURASIAN STUDIES SEPTEMBER 2020 Approval of the thesis: RISING SINOPHOBIA IN KYRGYZSTAN: THE ROLE OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION submitted by DOĞUKAN BAŞ in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Eurasian Studies, the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Yaşar KONDAKÇI Dean Graduate School of Social Sciences Assoc. Prof. Dr. Işık KUŞÇU BONNENFANT Head of Department Eurasian Studies Prof. Dr. Pınar KÖKSAL Supervisor Political Science and Public Administration Examining Committee Members: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Işık KUŞÇU BONNENFANT (Head of the Examining Committee) Middle East Technical University International Relations Prof. Dr. Pınar KÖKSAL (Supervisor) Middle East Technical University Political Science and Public Administration Assist. Prof. Dr. Yuliya BILETSKA Karabük University International Relations I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Doğukan Baş Signature : iii ABSTRACT RISING SINOPHOBIA IN KYRGYZSTAN: THE ROLE OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION BAŞ, Doğukan M.Sc., Eurasian Studies Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Pınar KÖKSAL September 2020, 131 pages In recent years, one of the major problems that Kyrgyzstan witnesses is rising Sinophobia among the local people due to problems related with increasing Chinese economic presence in the country. -

Failed Democratic Experience in Kyrgyzstan: 1990-2000 a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle Ea

FAILED DEMOCRATIC EXPERIENCE IN KYRGYZSTAN: 1990-2000 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY OURAN NIAZALIEV IN THE PARTIAL FULLFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION APRIL 2004 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences __________________________ Prof. Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for degree of Master of Science __________________________ Prof. Dr. Feride Acar Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. __________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Pınar Akçalı Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assist. Prof. Dr. Pınar Akcalı __________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Canan Aslan __________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Oktay F. Tanrısever __________________________ ABSTRACT FAILED DEMOCRATIC EXPERIENCE IN KYRGYZSTAN: 1990-2000 Niazaliev, Ouran M.Sc., Department of Political Science and Public Administration Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Pınar Akçalı April 2004, 158 p. This study seeks to analyze the process of transition and democratization in Kyrgyzstan from 1990 to 2000. The collapse of the Soviet Union opened new political perspectives for Kyrgyzstan and a chance to develop sovereign state based on democratic principles and values. Initially Kyrgyzstan attained some progress in building up a democratic state. However, in the second half of 1990s Kyrgyzstan shifted toward authoritarianism. Therefore, the full-scale transition to democracy has not been realized, and a well-functioning democracy has not been established. -

European Influences in Moldova Page 2

Master Thesis Human Geography Name : Marieke van Seeters Specialization : Europe; Borders, Governance and Identities University : Radboud University, Nijmegen Supervisor : Dr. M.M.E.M. Rutten Date : March 2010, Nijmegen Marieke van Seeters European influences in Moldova Page 2 Summary The past decades the European continent faced several major changes. Geographical changes but also political, economical and social-cultural shifts. One of the most debated topics is the European Union and its impact on and outside the continent. This thesis is about the external influence of the EU, on one of the countries which borders the EU directly; Moldova. Before its independency from the Soviet Union in 1991, it never existed as a sovereign state. Moldova was one of the countries which were carved out of history by the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact in 1940 as it became a Soviet State. The Soviet ideology was based on the creation of a separate Moldovan republic formed by an artificial Moldovan nation. Although the territory of the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic was a former part of the Romanian province Bessarabia, the Soviets emphasized the unique and distinct culture of the Moldovans. To underline this uniqueness they changed the Moldovan writing from Latin to Cyrillic to make Moldovans more distinct from Romanians. When Moldova became independent in 1991, the country struggled with questions about its national identity, including its continued existence as a separate nation. In the 1990s some Moldovan politicians focussed on the option of reintegration in a Greater Romania. However this did not work out as expected, or at least hoped for, because the many years under Soviet rule and delinkage from Romania had changed Moldovan society deeply. -

11 an Analysis of the Internal Structure of Kazakhstan's Political

11 Dosym SATPAEV An Analysis of the Internal Structure of Kazakhstan’s Political Elite and an Assessment of Political Risk Levels∗ Without understating the distinct peculiarities of Kazakhstan’s political development, it must be noted that the republic’s political system is not unique. From the view of a typology of political regimes, Kazakhstan possesses authoritarian elements that have the same pluses and minuses as dozens of other, similar political systems throughout the world. Objectivity, it must be noted that such regimes exist in the majority of post-Soviet states, although there has lately been an attempt by some ideologues to introduce terminological substitutes for authoritarianism, such as with the term “managed democracy.” The main characteristic of most authoritarian systems is the combina- tion of limited pluralism and possibilities for political participation with the existence of a more or less free economic space and successful market reforms. This is what has been happening in Kazakhstan, but it remains ∗ Editor’s note: The chapter was written in 2005, and the information contained here has not necessarily been updated. Personnel changes in 2006 and early 2007 include the fol- lowing: Timur Kulibaev became vice president of Samruk, the new holding company that manages the state shares of KazMunayGas and other top companies; Kairat Satybaldy is now the leader of the Muslim movement “Aq Orda”; Nurtai Abykaev was appointed am- bassador to Russia; Bulat Utemuratov became presidential property manager; and Marat Tazhin was appointed minister of foreign affairs. 283 Dosym SATPAEV important to determine which of the three types of authoritarian political systems—mobilized, conservative, or modernizing (that is, capable of political reform)—exists in Kazakhstan. -

2007 SC Playoff Summaries

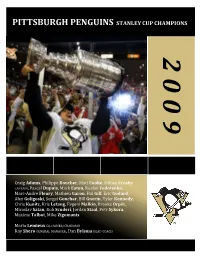

PITTSBURGH PENGUINS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 2 0 0 9 Craig Adams, Philippe Boucher, Matt Cooke, Sidney Crosby CAPTAIN, Pascal Dupuis, Mark Eaton, Ruslan Fedotenko, Marc-Andre Fleury, Mathieu Garon, Hal Gill, Eric Godard, Alex Goligoski, Sergei Gonchar, Bill Guerin, Tyler Kennedy, Chris Kunitz, Kris Letang, Evgeni Malkin, Brooks Orpik, Miroslav Satan, Rob Scuderi, Jordan Staal, Petr Sykora, Maxime Talbot, Mike Zigomanis Mario Lemieux CO-OWNER/CHAIRMAN Ray Shero GENERAL MANAGER, Dan Bylsma HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 2009 EASTERN CONFERENCE QUARTER—FINAL 1 BOSTON BRUINS 116 v. 8 MONTRÉAL CANADIENS 93 GM PETER CHIARELLI, HC CLAUDE JULIEN v. GM/HC BOB GAINEY BRUINS SWEEP SERIES Thursday, April 16 1900 h et on CBC Saturday, April 18 2000 h et on CBC MONTREAL 2 @ BOSTON 4 MONTREAL 1 @ BOSTON 5 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. BOSTON, Phil Kessel 1 (David Krejci, Chuck Kobasew) 13:11 1. BOSTON, Marc Savard 1 (Steve Montador, Phil Kessel) 9:59 PPG 2. BOSTON, David Krejci 1 (Michael Ryder, Milan Lucic) 14:41 2. BOSTON, Chuck Kobasew 1 (Mark Recchi, Patrice Bergeron) 15:12 3. -

Vladimir Voronin, President of Moldova (2001-2009) Anna Sous, RFE/RL Date of Interview: May 2015

Vladimir Voronin, president of Moldova (2001-2009) Anna Sous, RFE/RL Date of interview: May 2015 ************************ (This interview was conducted in Russian.) Anna Sous: You're not only a former president, but also a working politician, an opposition politician. You've been the leader of the Communist Party of Moldova for more than 20 years. Even at 74 years old, you're very active. How long is your typical workday? Vladimir Voronin: As long as necessary. Longer than people who have a standard working day. From 16 to 18 hours is normal. Anna Sous: Vladimir Nikolayevich, the Communist Party of Moldova is the only Communist party among the countries of the former Soviet Union that has managed to become the ruling party. How do you think Moldova's Communists differ from those in Russia? Vladimir Voronin: In ideological terms, our action plan isn't really any different. We don't differ from them in terms of being Communists, but in terms of the conditions we act in and work in -- the conditions in which we fight. Anna Sous: You were Moldova's minister of internal affairs. In 1989, when the ministry's building was set on fire during unrest in Chisinau, you didn't give the order to shoot. Later you said you wouldn't have given the command to shoot even if the ministry building had burned to the ground . Maybe this is how Moldova's Communists differ from those in Russia? Vladimir Voronin: Of course, the choices we had, and the situation we were in, were such that if I had given the order to shoot, it would have been recognized as constitutional and lawful. -

Seize the Press, Seize the Day: the Influence of Politically Affiliated Media in Moldova’S 2016 Elections

This policy brief series is part of the Media Enabling Democracy, Inclusion and Accountability in Moldova (MEDIA-M) project February 2018 | No 2 Seize the press, seize the day: The influence of politically affiliated media in Moldova’s 2016 elections Mihai Mogildea Introduction In Moldova, media ownership by oligarchs and political figures has reached the highest level in the last dec- ade. According to a report by the Association of Independent Press (API)1, four of the five TV channels with national coverage are controlled by the leader of the ruling Democratic Party (PDM), Vladimir Plahotniuc. Other media companies are managed by opposition politicians, mayors, former members of the parliament, and influential businessmen, who tend to adopt a restrictive policy on media content and promote specific political parties. The concentration of media resources in the hands of a few public officials has significant influence on the electorate, whose voting preferences can be manipulated through disinformation and fake news. This was visible during the second round of the 2016 presidential elections in Moldova, with powerful media owners undermining the campaign of the center-right, pro-European candidate, Maia Sandu, and helping Igor Dodon, a left-wing candidate and a strong supporter of Russia. This policy brief argues that political control over media Maia Sandu and Igor Dodon, and whether the audiovisual au- institutions in Moldova has an impact on election results. thorities sanctioned possible violations. Finally, this analysis Media concentration allows specific candidates to widely will conclude with a set of recommendations for depoliticiz- promote their messages, leading to unfair electoral ad- ing, both de jure and de facto, the private and public media vantage. -

India-Kyrgyz Republic Bilateral Relations

India-Kyrgyz Republic bilateral relations Historically, India has had close contacts with Central Asia, especially countries which were part of the Ancient Silk Route, including Kyrgyzstan. During the Soviet era, India and the then Kyrgyz Republic had limited political, economic and cultural contacts. Former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi visited Bishkek and Issyk-Kul Lake in 1985. Since the independence of Kyrgyz Republic on 31st August, 1991, India was among the first to establish diplomatic relations on 18 March 1992; the resident Mission of India was set up on 23 May 1994. Political relations Political ties with the Kyrgyz Republic have been traditionally warm and friendly. Kyrgyzstan also supports India’s bid for permanent seat at UNSC and India’s full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Both countries share common concerns on threat of terrorism, extremism and drug–trafficking. Since the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1992, the two countries have signed several framework agreements, including on Culture, Trade and Economic Cooperation, Civil Aviation, Investment Promotion and Protection, Avoidance of Double Taxation, Consular Convention etc. At the institutional level, the 8th round of Foreign Office Consultation was held in Bishkek on 27 April 2016. The Indian delegation was led by Ms. Sujata Mehta, Secretary (West) and Kyrgyz side was headed by Mr. Azamat Usenov, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs. An Indo-Kyrgyz Joint Commission on Trade, Economic, Scientific and Technological Cooperation was set up in 1992. The 8th Session of India-Kyrgyz Inter- Governmental Commission on Trade, Economic, Scientific and Technological Cooperation was held in Bishkek on 28 November 2016. -

Engaging Central Asia

ENGAGING CENTRAL ASIA ENGAGING CENTRAL ASIA THE EUROPEAN UNION’S NEW STRATEGY IN THE HEART OF EURASIA EDITED BY NEIL J. MELVIN CONTRIBUTORS BHAVNA DAVE MICHAEL DENISON MATTEO FUMAGALLI MICHAEL HALL NARGIS KASSENOVA DANIEL KIMMAGE NEIL J. MELVIN EUGHENIY ZHOVTIS CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN POLICY STUDIES BRUSSELS The Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) is an independent policy research institute based in Brussels. Its mission is to produce sound analytical research leading to constructive solutions to the challenges facing Europe today. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors writing in a personal capacity and do not necessarily reflect those of CEPS or any other institution with which the authors are associated. This study was carried out in the context of the broader work programme of CEPS on European Neighbourhood Policy, which is generously supported by the Compagnia di San Paolo and the Open Society Institute. ISBN-13: 978-92-9079-707-4 © Copyright 2008, Centre for European Policy Studies. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the Centre for European Policy Studies. Centre for European Policy Studies Place du Congrès 1, B-1000 Brussels Tel: 32 (0) 2 229.39.11 Fax: 32 (0) 2 219.41.51 e-mail: [email protected] internet: http://www.ceps.eu CONTENTS 1. Introduction Neil J. Melvin ................................................................................................. 1 2. Security Challenges in Central Asia: Implications for the EU’s Engagement Strategy Daniel Kimmage............................................................................................ -

Digital Oilfield Outlook Report-JWN

Digital Oilfield Outlook Report Opportunities and challenges for Digital Oilfield transformation B:9” T:8.5” S:8” Redefining Pipeline Operations. Identifying issues early is the key to making proactive decisions regarding pipeline safety, integrity and effi ciency. The Intelligent Pipeline Solution, with Pipeline Management from GE software and Accenture’s digital technology, business process and systems integration capabilities, works across your pipeline system to turn big data into actionable insights in near real-time. When GE and Accenture speak the language of analytics and change management, managers can make better decisions with more peace of mind. intelligentpipelinesolution.com B:11.5” S:10.5” T:11” This advertisement was prepared by BBDO New York Filename: P55430_GE_ITL_V2.indd CLIENT: General Electric Proof #: 2 Path: Studio:Volumes:Studio:MECHANIC..._ Created: 10-9-2015 1:29 PM PRODUCT: Predictivity Trade Ads - Oil and Gas Mechanicals:P55430_GE_ITL_V2.indd Saved: 10-9-2015 1:29 PM JOB#: P55430 Operators: Sekulovski, Jovan / Sekulovski, Jovan Printed: 10-9-2015 1:30 PM SPACE: Full Page 4/C Print Scale: None BLEED: 9” x 11.5” TRIM: 8.5” x 11” Fonts Ink Names SAFETY: 8” x 10.5” GE Inspira (ExtraBold, Regular), Arial Black (Regular) Cyan GUTTER: None Graphic Name Color Space Eff. Res. Magenta PUBS: CDN Energy Form IOT Report 140926_GE_Data_Pipelines_Final_4_CMYK_V2.psd (CMYK; 355 ppi), Yellow Black ISSUE: 10/28/15 GE_GreyCircles_LogoOnLeft_Horiz.ai, ACC_hpd_logo_.75x_white_ TRAFFIC: Mary Cook cmyk.eps ART BUYER: None ACCOUNT: Elizabeth Jacobs RETOUCH: None PRODUCTION: Michael Musano ART DIRECTOR: None COPYWRITER: None X1A Key insights New research from JuneWarren-Nickle’s Energy Group, with partners GE and Accenture, shows that Canadian oil and gas professionals see a great deal of potential in adopting Digital Oilfield technology across industry verticals. -

The Oil Boom After Spindletop

425 11/18/02 10:41 AM Page 420 Why It Matters Now The Oil Boom Petroleum refining became the 2 leading Texas industry, and oil remains important in the Texas After Spindletop economy today. TERMS & NAMES OBJECTIVES MAIN IDEA boomtown, refinery, Humble 1. Analyze the effects of scientific discov- After Spindletop, the race was on to Oil and Refining Company, eries and technological advances on the discover oil in other parts of Texas. wildcatter, oil strike, oil and gas industry. In just 30 years, wells in all regions Columbus M. “Dad” Joiner, 2. Explain how C. M. “Dad” Joiner’s work of the state made Texas the world hot oil affected Texas. leader in oil production. 3. Trace the boom-and-bust cycle of oil and gas during the 1920s and 1930s. With the discovery of oil at Spindletop, thousands of fortune seekers flooded into Texas, turning small towns into overcrowded cities almost overnight. An oil worker’s wife described life in East Texas in 1931. There were people living in tents with children. There were a lot of them that had these great big old cardboard boxes draped around trees, living under the trees. And any- and everywhere in the world they could live, they lived. Some were just living in their cars, and a truck if they had a truck. And I tell you, that was bad. Just no place to stay whatsoever. Mary Rogers, interview in Life in the Oil Fields Oil, Oil Everywhere The oil boom of the 1920s and 1930s caused sudden, tremendous growth in Texas. -

The Impact of the Fracking Boom on Arab Oil Producers

The Impact of the Fracking Boom on Arab Oil Producers April 4, 2016 Lutz Kilian University of Michigan CEPR Abstract: This article contributes to the debate about the impact of the U.S. fracking boom on U.S. oil imports, on Arab oil exports, and on the global price of crude oil. First, I investigate the extent to which this oil boom has caused Arab oil exports to the United States to decline since late 2008. Second, I examine to what extent increased U.S. exports of refined products made from domestically produced crude oil have caused Arab oil exports to the rest of the world to decline. Third, the article quantifies by how much increased U.S. tight oil production has lowered the global price of oil. Using a novel econometric methodology, it is shown that in mid-2014, for example, the Brent price of crude oil was lower by $10 than it would have been in the absence of the fracking boom. I find no evidence that fracking was a major cause of the $64 decline in the Brent price of oil from July 2014 to January 2015, however. Fourth, I provide evidence that the decline in Saudi foreign exchange reserves between mid-2014 and August 2015 would have been reduced by 27 percent in the absence of the fracking boom. Finally, I discuss the policy implications of my findings for Saudi Arabia and for other Arab oil producers. JEL Code: Q43, Q33, F14 Key Words: Arab oil producers; Saudi Arabia; shale oil; tight oil; oil price; oil imports; oil exports; refined product exports; oil revenue; foreign exchange reserves; oil supply shock.