Interview with Sir Percy Cradock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barn G Stables 57-78 on Account of SMYTZER's LODGE, Gnarwarre

Barn G Stables 57-78 On Account of SMYTZER'S LODGE, Gnarwarre. Lot 281 BAY COLT 10 (Branded nr sh. 4 off sh. Foaled 12th November, 2004.) Danehill........................... by Danzig ....................... (SIRE) Danehill Dancer (Ire) ...... Mira Adonde ................... by Sharpen Up ................ CHOISIR....................... Lunchtime (GB) .............. by Silly Season ............... Great Selection ............... Pensive Mood.................. by Biscay........................ (DAM) Hethersett........................ by Hugh Lupus ............... Blakeney......................... PERCY'S GIRL (IRE).. Windmill Girl.................. by Hornbeam .................. 1988 Sassafras.......................... by Sheshoon.................... Laughing Girl.................. Violetta ........................... by Pinza.......................... By CHOISIR (Ch., 1999) Champion 2YO Colt 2001/02, 3YO Sprinter 2002/03; won 7 races and $2,230,033 inc. Royal Ascot Golden Jubilee S. Gr 1, VRC Lightning S. Gr 1, Royal Ascot King's Stand S. Gr 2, VRC Emirates Classic Gr 2. 2d Newmarket July Cup Gr 1, AJC Sires' Produce S. Gr 1. 3d STC Golden Slipper S. Gr 1, MRC Caulfield Guineas Gr 1, AJC Champagne S. Gr 1, MRC Oakleigh P. Gr 1; his oldest progeny are yearlings. 1st DAM Percy's Girl (Ire), by Blakeney. 2 wins at 1¼m., 10½f. inc. Sandown Mitre Graduation S. 2d Ayr Doonside Cup L, York Galtres S. L. 4th Newmarket Godolphin S. L. Sister to PERCY'S LASS (dam of SIR PERCY, Blue Lion). Half-sister to BRAISWICK (dam of ICKLINGHAM). This is her ninth foal. Her eighth foal is a 2YO, 4 raced, 3 winners- MISS CORINNE (f by Mark Of Esteem). 5 wins 1500 to 2350m. in Italy. BYSSHE (f by Linamix). 2 wins at 2400, 2600m. in France. PERCY ISLE (c by Doyoun). 1 win at 1½m. -

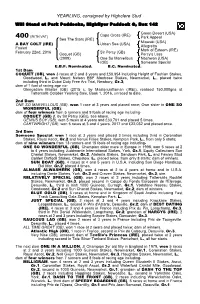

YEARLING, Consigned by Highclere Stud

YEARLING, consigned by Highclere Stud Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock G, Box 142 Green Desert (USA) Cape Cross (IRE) 400 (WITH VAT) Park Appeal Sea The Stars (IRE) Miswaki (USA) A BAY COLT (IRE) Urban Sea (USA) Allegretta Foaled Mark of Esteem (IRE) February 22nd, 2016 Sir Percy (GB) Coquet (GB) Percy's Lass (2009) One So Marvellous Nashwan (USA) (GB) Someone Special E.B.F. Nominated. B.C. Nominated. 1st Dam COQUET (GB), won 3 races at 2 and 3 years and £50,954 including Height of Fashion Stakes, Goodwood, L. and Mount Nelson EBF Montrose Stakes, Newmarket, L., placed twice including third in Dubai Duty Free Arc Trial, Newbury, Gr.3; dam of 1 foal of racing age viz- Glencadam Master (GB) (2015 c. by Mastercraftsman (IRE)), realised 150,000gns at Tattersalls October Yearling Sale, Book 1, 2016, unraced to date. 2nd Dam ONE SO MARVELLOUS (GB), won 1 race at 3 years and placed once; Own sister to ONE SO WONDERFUL (GB); dam of four winners from 5 runners and 9 foals of racing age including- COQUET (GB) (f. by Sir Percy (GB)), see above. GENIUS BOY (GB), won 5 races at 4 years and £33,701 and placed 5 times. CARTWRIGHT (GB), won 5 races at 3 and 4 years, 2017 and £22,032 and placed once. 3rd Dam Someone Special, won 1 race at 3 years and placed 3 times including third in Coronation Stakes, Royal Ascot, Gr.2 and Venus Fillies Stakes, Kempton Park, L., from only 5 starts; dam of nine winners from 13 runners and 15 foals of racing age including- ONE SO WONDERFUL (GB), Champion older mare in Europe in 1998, won 5 races at 2 to 4 years including Juddmonte International Stakes, York, Gr.1, Equity Collections Sun Chariot Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2, Atalanta Stakes, Sandown Park, L. -

HORSE in TRAINING, Consigned by Jamesfield Stables (J. Tate) the Property of Darley Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock N, Box 199

HORSE IN TRAINING, consigned by Jamesfield Stables (J. Tate) the Property of Darley Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock N, Box 199 Danehill (USA) Danetime (IRE) 308 (WITH VAT) Allegheny River (USA) Myboycharlie (IRE) MOONLIT SKY Rousillon (USA) Dulceata (IRE) (GB) Snowtop (2011) Seeking The Gold Mr Prospector (USA) A Bay Colt Calico Moon (USA) (USA) Con Game (USA) (2001) Strawberry Roan Sadler's Wells (USA) (IRE) Doff The Derby (USA) MOONLIT SKY (GB), placed twice at 3 years, 2014. Highest BHA rating 66 (Flat) Latest BHA rating 66 (Flat) (prior to compilation) ALL WEATHER 3 runs 2 pl £986 1st Dam CALICO MOON (USA), ran in France at 2 years; dam of two winners from 5 runners and 5 foals of racing age viz- SILK COTTON (USA) (2006 f. by Giant's Causeway (USA)), won 4 races at 4 and 5 years in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and £70,441 and placed 11 times. CRUACHAN (IRE) (2009 g. by Authorized (IRE)), placed once at 3 years; also won 1 race over hurdles and placed 3 times. Moonlit Sky (GB) (2011 c. by Myboycharlie (IRE)), see above. She also has a 2013 filly by Sir Percy (GB). 2nd Dam STRAWBERRY ROAN (IRE) , won 3 races including Derrinstown Stud 1000 Guineas Trial, Leopardstown, L. and Eyrefield 2yo Stakes, Leopardstown, L. , second in Irish 1000 Guineas, Curragh, Gr.1 , third in Meld Stakes, Curragh, Gr.3 ; Own sister to IMAGINE (IRE) ; dam of three winners from 7 runners and 12 foals of racing age including- Berry Blaze (IRE) (f. by Danehill Dancer (IRE)), won 2 races at 3 years in South Africa and £35,633 and second in Korea Racing Authority Fillies Guineas, Greyville, Gr.2 , Gerald Rosenberg Stakes, Turffontein, Gr.2 , third in South African Fillies Classic, Turffontein, Gr.1 , Woolavington 2000, Greyville, Gr.1 and Gold Bracelet Stakes, Greyville, Gr.2 . -

EUROPEAN PEDIGREE for TORNEQUETA MAY (GB) - Three Dams

EUROPEAN PEDIGREE for TORNEQUETA MAY (GB) - Three Dams Anabaa (USA) Danzig (USA) Sire: (Bay 1992) Balbonella (FR) STYLE VENDOME (FR) (Grey 2010) Place Vendome (FR) Dr Fong (USA) TORNEQUETA MAY (GB) (Grey 2004) Mediaeval (FR) (Bay filly 2015) Green Desert (USA) Danzig (USA) Dam: (Bay 1983) Foreign Courier (USA) ALABASTRINE (GB) (Grey 2000) Alruccaba Crystal Palace (FR) (Brown/Grey 1983) Allara 3Sx3D Danzig (USA) TORNEQUETA MAY (GB) (2015 filly by STYLE VENDOME (FR)), unraced in GB/IRE. 1st dam. ALABASTRINE (GB) (2000 mare by GREEN DESERT (USA)); in GB/IRE, placed once, £1,145 at 3 years, exported to France; dam of 11 known foals; 6 known runners; 4 known winners. HAIL CAESAR (IRE) (2006 gelding by MONTJEU (IRE)); in GB/IRE, won 1 race, £8,638 at 2 years, won 1 race and placed 4 times, £19,638 at 3 years; in Belgium, won 1 race, £1,293 at 5 years, won 2 races and placed twice, £4,084 at 6 years; in France, unplaced at 2 years, unplaced at 3 years, unplaced at 6 years, unplaced at 10 years; in GB/IRE over hurdles, won 1 race and placed 4 times, £11,137 at 4 years, placed once, £143 at 5 years; in GB/IRE over fences, placed once, £430 at 5 years, exported to Belgium. ALBASPINA (IRE) (2009 mare by SELKIRK (USA)); in GB/IRE, won 1 race, £2,264 at 2 years, placed twice, £1,819 at 3 years; dam of- Hiss Beau (QTR) (2014 filly by ROYAL APPLAUSE (GB)); in Qatar, unplaced at 3 years. -

EUROPEAN PEDIGREE for WHOLE GRAIN (GB) - Three Dams

EUROPEAN PEDIGREE for WHOLE GRAIN (GB) - Three Dams Danzig (USA) Northern Dancer Sire: (Bay 1977) Pas de Nom (USA) POLISH PRECEDENT (USA) (Bay 1986) Past Example (USA) Buckpasser WHOLE GRAIN (GB) (Chesnut 1976) Bold Example (USA) (Bay mare 2001) Mill Reef (USA) Never Bend Dam: (Bay 1968) Milan Mill MILL LINE (Bay 1985) Quay Line High Line (Bay 1976) Dark Finale WHOLE GRAIN (GB) (2001 mare by POLISH PRECEDENT (USA)); in GB/IRE, unplaced at 2 years, placed once, £434 at 3 years, unplaced at 4 years, unplaced at 5 years; in France, placed twice, £2,872 at 4 years; dam of 6 known foals; 1 known runner; 1 known winner. Tioman Two (GB) (2007 gelding by RED RANSOM (USA)), unraced in GB/IRE. LOUIS THE PIOUS (GB) (2008 gelding by HOLY ROMAN EMPEROR (IRE)); in GB/IRE, placed once, £265 at 2 years, won 4 races and placed 4 times, £29,057 at 3 years, placed 4 times, £29,946 at 4 years, won 1 race and placed once, £44,455 at 5 years, placed once, £9,625 at 6 years. (2009 mare by TEOFILO (IRE)). Oatmeal (GB) (2011 filly by DALAKHANI (IRE)), unraced in GB/IRE, exported to France. Swaheen (GB) (2012 colt by LAWMAN (FR)), unraced in GB/IRE. (2013 colt by SIR PERCY (GB)). No Return in 2010. 1st dam. MILL LINE (1985 mare by MILL REEF (USA)); in GB/IRE, won 1 race and placed 3 times, £3,473 at 3 years, WON Royal British Legion Stakes, Doncaster, 1988, SECOND Links Stakes, Redcar, 1988, exported to USA; dam of 13 known foals; 11 known runners; 9 known winners. -

HORSE in TRAINING, the Property of Juddmonte Farms

HORSE IN TRAINING, the Property of Juddmonte Farms Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock H, Box 126 Danzig (USA) Danehill (USA) 551 (WITH VAT) Razyana (USA) Cacique (IRE) Kahyasi PRESTO (GB) Hasili (IRE) Kerali (2015) Mr Prospector (USA) A Bay Gelding Distant View (USA) Allegro Viva (USA) Seven Springs (USA) (2002) Nijinsky (CAN) Musicanti (USA) Populi (USA) PRESTO (GB), unraced, own brother to CANTICUM (GB). 1st Dam ALLEGRO VIVA (USA), unraced; Own sister to DISTANT MUSIC (USA); dam of five winners from 5 runners and 7 foals of racing age viz- CANTICUM (GB) (2009 c. by Cacique (IRE)), won 2 races at 3 years in France and £131,750 including Qatar Prix Chaudenay, Longchamp, Gr.2, placed 3 times including second in Prix de Lutece, Longchamp, Gr.3 and Prix Michel Houyvet, Deauville, L. UPHOLD (GB) (2007 g. by Oasis Dream (GB)), won 10 races at 3 to 6 years at home and in France and £89,239 and placed 22 times. BUSY STREET (GB) (2012 g. by Champs Elysees (GB)), won 1 race at 3 years and £13,003 and placed 11 times; also placed once in a N.H. Flat Race. FENGATE (GB) (2013 f. by Champs Elysees (GB)), won 1 race at 3 years in France and £21,443 and placed 6 times. ALLEGREZZA (GB) (2011 f. by Sir Percy (GB)), won 1 race at 3 years in France, £10,417. Presto (GB) (2015 g. by Cacique (IRE)), see above. She also has a 2017 colt by Kyllachy (GB). 2nd Dam MUSICANTI (USA), won 1 race in France and £19,669 and placed 4 times; dam of four winners from 9 runners and 11 foals of racing age viz- DISTANT MUSIC (USA) (c. -

Sue Johnson & John Bromfield Owner Profile

The SPRING 2013 KINGSCLERE Quarter THE PARK HOUSE STABLES NEWSLETTER The KINGSCLERE Quarter THE fter what has seemed like an eternity, the dark, cold and often wet days of the winter months are A finally subsiding and spring will be welcomed with open arms by all at Kingsclere when it eventually arrives! The combination of short days, bad weather and lack of racecourse activity make the off season a tough period for everyone working at Park House but the load has been made a little lighter this year with the exciting prospect of what appears to be a very strong team of horses for the coming flat season. It is always a benefit to any yard to have a strong team of older SIDE GLANCE braving the elements horses and some familiar faces as well as a couple of exciting new Front cover: Rob Hornby leading the string home, additions means we have strength in depth in this department. Summer 2012 Back cover: ‘I’m ready for the flat season – are you’? Side Glance has been a stable stalwart for the past three flat Flora and Will seasons and his achievements in 2012 were a testament to his consistency and versatility. As winner of the Group 3 Diomed Stakes at Epsom in June, he went on to be placed at Group 2 and Group CONTENTS 1 level most notably when he chased home the mighty Frankel, at a respectable distance, in the Queen Anne Stakes with only the top THE SEASON AHEAD 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 & 8 class miler Excelebration in between! Side Glance now looks ready ANDREW BALDING for the step up to ten furlongs. -

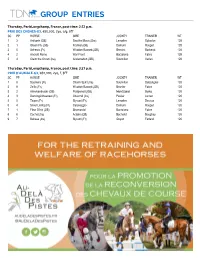

Group Entries

GROUP ENTRIES Thursday, ParisLongchamp, France, post time: 2.52 p.m. PRIX DES CHENES-G3, €80,000, 2yo, c/g, 8fT SC PP HORSE SIRE JOCKEY TRAINER WT 1 3 Antharis (GB) Sea the Moon (Ger) Lemaitre Suborics 128 2 1 Green Fly (GB) Frankel (GB) Demuro Rouget 128 3 5 Scherzo (Fr) Wootton Bassett (GB) Benoist Barberot 128 4 2 Ancient Rome War Front Barzalona Fabre 128 5 4 Claim the Crown (Ire) Acclamation (GB) Soumillon Varian 128 Thursday, ParisLongchamp, France, post time: 3.27 p.m. PRIX D’AUMALE-G3, €80,000, 2yo, f, 8fT SC PP HORSE SIRE JOCKEY TRAINER WT 1 8 Soumera (Fr) Charm Spirit (Ire) Soumillon Delzangles 126 2 9 Zellie (Fr) Wootton Bassett (GB) Besnier Fabre 126 3 2 Almohandesah (GB) Postponed (GB) Mendizabal Burke 126 4 3 Dancinginthestreet (Fr) Churchill (Ire) Peslier Lerner 126 5 5 Txope (Fr) Siyouni (Fr) Lemaitre Decouz 126 6 4 Silver Lining (Fr) Caravaggio Demuro Rouget 126 7 1 Fleur D’Iris (GB) Shamardal Barzalona Fabre 126 8 6 Cachet (Ire) Aclaim (GB) Bachelot Boughey 126 9 7 Bahasa (Ire) Siyouni (Fr) Guyon Ferland 126 Thursday, Doncaster, Britain, post time: 2.40 p.m. THE CAZOO MAY HILL STAKES (CLASS 1) (GROUP 2)-G2, £112,500, 8fT SC HORSE SIRE OWNER TRAINER JOCKEY WT 1 Banshee (Ire) Iffraaj (GB) Mr B. E. Nielsen Brian O'Rourke Oisin Murphy 126 2 Inspiral (GB) Frankel (GB) Cheveley Park Stud John & Thady Gosden Frankie Dettori 126 3 Kawida (GB) Sir Percy (GB) Miss K. Rausing Ed Walker Hollie Doyle 126 4 Prosperous Voyage (Ire) Zoffany (Ire) Mr P Stokes & Mr S Krase Ralph Beckett Rob Hornby 126 5 Renaissance (Ire) Caravaggio Sir Robert Ogden David O'Meara Daniel Tudhope 126 6 Rolling The Dice (Ire) Mehmas (Ire) Mr Hassan Al Abdulmalik Hilal Kobeissi Daniel Muscutt 126 7 Speak (GB) Sea The Moon (Ger) Mr George Strawbridge Andrew Balding David Probert 126 Breeders: 1-Bjorn Nielsen, 2-Cheveley Park Stud Limited, 3-Miss K. -

Waldgeist (GB)

equineline.com Product 40P 04/15/20 11:39:02 EDT Waldgeist (GB) Chestnut Horse; Feb 17, 2014 Northern Dancer, 61 b Sadler's Wells, 81 b Fairy Bridge, 75 b $Galileo (IRE), 98 b Miswaki, 78 ch Waldgeist (GB) Urban Sea, 89 ch Allegretta (GB), 78 ch Foaled in Great Britain =Konigsstuhl (GER), 76 dk b/ =Monsun (GER), 90 br =Waldlerche (GB), 09 ch =Mosella (GER), 85 b $Mark of Esteem (IRE), 93 b =Waldmark (GER), 00 ch =Wurftaube (GER), 93 ch By GALILEO (IRE) (1998). European Champion, Classic winner of $2,245,373 USA in England and Ireland, Budweiser Irish Derby [G1], etc. Leading sire 20 times in Czechoslovakia/Czech Republic, England, France, Ireland and Slovakia, sire of 16 crops of racing age, 2901 foals, 2137 starters, 313 stakes winners, 14 champions, 1448 winners of 3806 races and earning $262,625,252 USA, including Frankel (European Horse of the year, $4,789,144 USA, QIPCO Two Thousand Guineas [G1], etc.), New Approach (European Champion twice, $3,885,308 USA, Vodafone Epsom Derby [G1], etc.), Cape Blanco (IRE) (Champion in U.S., $3,855,665 USA, Dubai Duty Free Irish Derby [G1], etc.), Wells (Champion in Australia, to 12, 2019, $1,093,211 USA, 2nd Andrew Ramsden S. [L]). 1st dam =WALDLERCHE (GB), by =Monsun (GER). Winner in 3 starts at 2 and 3 in FR , placed in 1 start at 3 in GER, $91,543 (USA), Prix Penelope [G3], 2nd Honda Nereide-Rennen [L]. Dam of 5 foals, 4 to race, 4 winners-- WALDGEIST (GB) (c. by $Galileo (IRE)). -

HEADLINE NEWS • 6/4/06 • PAGE 2 of 11

PROPOSED HANGS ON IN HEADLINE MILADY...p5 NEWS For information about TDN, DELIVERED EACH NIGHT BY FAX AND FREE BY E-MAIL TO SUBSCRIBERS OF call 732-747-8060. www.thoroughbreddailynews.com SUNDAY, JUNE 4, 2006 DRAMA ON THE DOWNS THE NAME GAME There were four horses on the line at the finish of the With major contenders from Britain, Ireland and Ger- 227th renewal of yesterday=s G1 Vodafone Derby at many in the line-up for today=s G1 Prix du Jockey-Club Epsom Downs, but attention was at Chantilly, Paul Vidal=s Best Name (GB) (King's Best) torn between the victorious Sir faces a stern test, but the easy Percy (GB) (Mark of Esteem option has never been a consid- {Ire}), and the stricken Horatio eration for this colt. The bay Nelson (Ire) (Danehill), who broke made just one start at two, and down as the field raced toward justified his stable=s confidence the wire. Horatio Nelson frac- when running just a short head tured the cannon bone and behind Linda's Lad (GB) in the sesamoids of his right front leg G3 Prix de Conde at Longchamp and had to be euthanized. The in October. He returned to record tragedy left a pall over the gallant a comfortable success in the triumph of Sir Percy, who drove Listed Prix de Courcelles at Robert Collet APRH up the rail to earn a short-head Longchamp Apr. 9, and bids to verdict over the 66-1 maiden provide conditioner Robert Collet with an overdue first Sir Percy Getty Images Dragon Dancer (GB) (Sadler=s Jockey-Club. -

YEARLING, Consigned by Kirtlington Stud

YEARLING, consigned by Kirtlington Stud Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock K, Box 187 Green Desert (USA) Cape Cross (IRE) 502 (WITH VAT) Park Appeal Golden Horn (GB) Dubai Destination (USA) A BAY FILLY (GB) Fleche d'Or (GB) Nuryana Foaled Polar Falcon (USA) February 11th, 2018 Pivotal (GB) Pivotting (GB) Fearless Revival (2006) Spinning The Yarn Barathea (IRE) (GB) Colorspin (FR) E.B.F. Nominated. B.C. Nominated. 1st Dam PIVOTTING (GB), unraced; dam of two winners from 4 runners and 6 foals of racing age viz- GOOD OLD BOY LUKEY (GB) (2011 c. by Selkirk (USA)), won 4 races at 2 and 3 years at home and in Hong Kong and £195,211 including 32red.com Superlative Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2, placed 6 times. Oakley Girl (GB) (2012 f. by Sir Percy (GB)), won 3 races at 3 and 4 years and £58,573 and placed 9 times including second in EBF Conqueror Stakes, Goodwood, L., third in EBF Hoppings Stakes, Newcastle, L. and Kentucky Downs Ladies Marathon Stakes, Kentucky Downs, L. and fourth in Princess Elizabeth Stakes, Epsom Downs, Gr.3. Hadeeya (GB) (2010 f. by Oratorio (IRE)), unplaced; dam of- Ropey Guest (GB), placed 3 times at 2 years, 2019 including third in Wooldridge Pat Eddery Stakes, Ascot, L. and fourth in Superlative Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2. (2017 f. by Sepoy (AUS)). 2nd Dam SPINNING THE YARN (GB), ran once at 3 years; dam of three winners from 6 runners and 8 foals of racing age including- NECKLACE (GB) (f. by Darshaan), Champion 2yr old filly in Ireland in 2003, won 2 races at 2 years and £210,142 viz Moyglare Stud Stakes, Curragh, Gr.1 and Robert H Griffin Debutante Stakes, Curragh, Gr.3, placed 3 times including third in Beverly D Stakes, Arlington International, Gr.1; dam of winners. -

Bill Oppenheim, December 13, 2006–Top Value: George Washington from the DESK OF

Bill Oppenheim, December 13, 2006–Top Value: George Washington FROM THE DESK OF... Bill Oppenheim TOP VALUE: GEORGE WASHINGTON It=s not often the market leads Coolmore--usually, it=s the other way around. So the fact that even they evidently succumbed to the hype about George Washington=s quirks, by setting his initial stud fee at what, in my opinion, is half price compared to his >true= market value, is a hint that shrewd breeders on both sides of the Pond should be taking. Here=s your chance to breed to a horse who should be standing at stud for $150,000 for i60,000--roughly the equivalent of $75,000. That=s why--in spite of the fact that >value= stallions usually stand for either side of $10,000-- George Washington is my choice as >number one value stallion= of the year for 2007. He=s a spectacular individual (top-priced yearling of his year in Europe: 1,150,000gns at Tattersalls October 1 in 2004). He=s by Danehill, and he=s closely related to the top-class Grandera out of an Alysheba mare bred by the Wildensteins. As a two-year-old, he ran an RPR (Racing Post Rating, roughly the equivalent of Timeform) 121 when running off (by eight lengths) with the G1 Phoenix S., and followed that up with a win (not nearly so high a rating, though) in the G1 National $12,500 live foal (859) 233-4252 www.claibornefarm.com S., always Ireland=s best race for two-year-olds. This year, he won the G1 2000 Guineas first time out (RPR 127), defeating subsequent Derby winner Sir Percy, As a three-year-old Azamour won the St.