Law and Athlete Drug Testing in Canada Joseph De Pencier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPC Mentor List April 2017 External Province Mentor Credential Level

SPC Mentor List April 2017 External Province Mentor Credential Level Contact and Location Areas of Interest AB Amy Bauele Diploma 403-202-6565 Personal sport experience: Provincial level slo-pitch and National level figure skating Calgary, AB Physiotherapist sport experience (primary areas of current focus): hockey, figure skating, freestyle skiing AB Daniel Crumback Diploma [email protected] Exercise Physiology, Physiological Testing, Respiratory Testing 780-574-1907 and Training, Performance Training, Advanced FMS/SFMA, Injury Prevention, Tactical Athlete Assessment and Treatment Lancaster Park, AB FR Instructor, Sport Taping Instructor, Sport Equipment Instructor Running, Triathlon, Cycling, Mountain Biking, Skiing, Hockey AB Leigh Garvie Diploma [email protected] Clinical practice, have Diploma of Advanced Manual Therapy & 780-451-6263 manipulation, IMS Coronation Physiotherapy Sports: swimming, ultra trail running, rugby, gymnastics, figure skating, track, diving Edmonton, AB Page 1 of 16 SPC Mentor List April 2017 External Province Mentor Credential Level Contact and Location Areas of Interest AB Susan Masstiti Diploma [email protected] Injury Prevention, Movement as Medicine, Optimal Recovery in Elite Sport, Manual Therapy Canmore, AB Clinical Specialist Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy, UBC Gunn Intramuscular Stimulation Instructor, Certificate Medical Acupuncture innovative and integrative solutions and strategies to stimulate thebody's innate wisdom to heal. Our role as physiotherapists is ultimately to work in collaboration with you (and other professionals) to restore your physical wellness. Health crises can challenge our physical capacities. This is as true for a soccer player experiencing a knee injury, as for a parent who is dealing with chronic neck or back pain. Susan’s expertise has helped Olympic and recreational athletes, as well as inspired many to restore their health. -

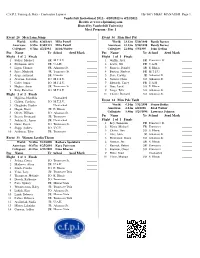

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

C.F.P.I. Timing & Data - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER Page 1 Vanderbilt Invitational 2012 - 4/20/2012 to 4/21/2012 Results at www.cfpitiming.com Hosted by Vanderbilt University Meet Program - Day 1 Event 26 Men Long Jump Event 36 Men Shot Put World: 8.95m 8/30/1991 Mike Powell World: 23.12m 5/20/1990 Randy Barnes American: 8.95m 8/30/1991 Mike Powell American: 23.13m 5/20/1990 Randy Barnes Collegiate: 8.74m 4/2/1994 Erick Walder Collegiate: 22.00m 6/3/1995 John Godina Pos NameYr School Seed Mark Pos NameYr School Seed Mark Flight 1 of 2 Finals Flight 1 of 1 Finals 1 Stokes, Michael SR M.T.S.U. _________ 1 Griffin, Alex FR Tennessee St. _________ 2 Buchanan, Alex FR U.A.H. _________ 2 Lester, Wil FR U.A.H. _________ 3 Ligon, Thomas FR Arkansas St. _________ 3 Romero, Donald SR E. Illinois _________ 4 Price, Markeith JR Tennessee St. _________ 4 Bastien, Shubert FR M.T.S.U. _________ 5 diogo, raymond SR Uganda _________ 5 Pace, Corwin JR Arkansas St. _________ 6 Atosona, Solomon SO M.T.S.U. _________ 6 Nicasio, Chris SO Arkansas St. _________ 7 Cadet, Junior SO M.T.S.U. _________ 7 Edwards, Casey FR U.A.H. _________ 8 Hughes, Avian SR Tennessee St. _________ 8 Diaz, Jared SO E. Illinois _________ 9 Rory, Kameron SO M.T.S.U. _________ 9 Lingo, Tyler SO Arkansas St. _________ Flight 2 of 2 Finals 10 Chavez, Richard SO Arkansas St. -

Chasing the Dream: Canadian Track and Field Student-Athlete Migration to the NCAA Division I

Chasing the Dream: Canadian Track and Field Student-Athlete Migration to the NCAA Division I by Sarah Boyle A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto © Copyright by Sarah Boyle 2017 Chasing the Dream: Canadian Track and Field Student-Athlete Migration to the NCAA Division I Sarah Boyle Master of Science Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto 2017 Abstract While there is interest in understanding the motivations and experiences of student-athletes who migrate to the NCAA, there is a lack of data quantifying migration to the NCAA. Specifically, in the case of track and field, the last quantitative effort to identify Canadian student-athlete migration to the NCAA was published in the early 1990’s by John Bale. Using descriptive research methods, this thesis defines the population of Canadian track and field student-athletes who migrated to the NCAA DI between the 2005/06 and 2012/13 academic years. Results indicate that during this eight year period, 562 Canadian student-athletes migrated to the NCAA Division I to participate in track and field. Canadian track and field student-athletes who migrate to the NCAA Division I comprise more than half of the athletes competing internationally for the Canadian National Track and Field Team. ii Acknowledgments This project would not have been completed if it were not for the support of my supervisors, Peter Donnelly and Michael Atkinson. With a three-year hiatus to complete my Juris Doctorate at Osgoode Hall Law School, I have been afforded time to reflect on this research and appreciate the fruits of collecting systemic research data. -

2004-05 Swimming Brochure

CAROLINA SWIMMING & DIVING: HISTORY & TRADITION The University of North Carolina’s proud swimming and diving heritage predates America’s entry into World War II. On January 23, 1939, Tar Heel swimmers and divers par- ticipated in the school’s first varsity intercolle- giate swimming meet against the University of Virginia at historic Bowman Gray Pool on the UNC campus. Since 1939, Carolina’s men’s teams have posted a cumulative dual-meet record of 512- 174-1, a winning percentage of .746. Carolina teams have captured 14 Southern Conference team championships and 17 Atlantic Coast Conference team titles, while posting a 60-3 (.952) Southern Conference dual-meet mark and a 236-59-1 (.799) record in ACC dual meets. On 28 occasions, UNC men’s teams have finished amongst the Top 25 teams at the NCAA Championships. Carolina swimmers have also won four indi- vidual NCAA championships in the history of the program. Although Carolina had women’s swimming teams in the early 1970s competing in AIAW competitions as part of the UNC physical Charlie Krepp is the only men’s swimmer in University of North Carolina history to win multiple indi- vidual NCAA championships. A gifted backstroker, Krepp used the advantage of competing in his home education department, the women’s swim- pool when Bowman Gray Pool served as the host facility for the 1957 NCAA Championships. He won ming and diving program was not elevated to titles in the 100-yard and 200-yard backstroke titles under the aegis of head coach Ralph Casey. varsity status and taken under the aegis of the intercollegiate athletic program until the Twenty-seven of UNC’s 31 women’s teams Jamerson 1974-75 school year. -

Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games Nomination Criteria

Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games Nomination Criteria Selection Criteria Amendments • February 19, 2021 o Section 1.2: . Removed reference to NACAC Combined Events Championships, which has been cancelled. The dates and location of the Canadian Combined Events Trials is now to-be-confirmed. Moved the Final Nomination for Marathon and Race Walk to July 2 to align with all other events. Moved the final declaration deadline for all events to June 10, 2021. Updated dates for: Final Preparation Camp, On-site Decision Making Authority, Athletics Competition and Departing Japan o Section 1.3: . Removed requirement to participate in Canadian Championships. Added requirement to comply with COVID-19 countermeasures. o Section 1.6: Added reference to Reserve Athletes. o Section 3: Removed requirement to participate in Canadian Championships. o Section 4.1 . Step 2: Removed: “For the avoidance of doubt, the NTC will not nominate athletes for individual events who are only qualified to be entered due to World Athletics’ “reallocations due to unused quota places” after July 1, 2021 (June 2, 2021 for Marathon and Race Walk).” . Final Nomination Meeting: Added prioritization process for athletes qualifying for both the Women’s Marathon and 10,000m. o Section 4.2: . Removed: “AC will not accept any offers of unused quota places for relay teams made after July 1, 2021;” . Step 1: Removed automatic nomination for national champions. o Section 8: Added language regarding possible further amendments necessitated by COVID-19. • October 6, 2020 o Section 1.2: Updated qualification period to match World Athletics adjustments for Marathon and 50k Race Walk. Updated dates for NACAC Combined Events Championships (Athletics Canada Combined Events Trials). -

SCOREBOARD Cent of the Vote Respectively

20—MANCHESTER HERALD, Tuesday, November 6,1990 Reynolds, Barnes face ban from the 1992 Olympics WEDNESDAY LONDON (AP) — Facing a possible two-year suspen metabolites of the banned substance methyli'*ctosicrone, sion that could prevent him from competing in the 1992 .. There is no room for steroids or and a second analysis carried out on Sept. 25, 1990, con Olympics, Butch Reynolds, the world record-holder in firmed their presence. the 400 meters, deni^ he has ever used steroids and said drug abuse in my life___People who LOCAL NEWS INSIDE “The case was then investigated by the lAAF doping drug tests that turned up positive “cannot be medically know Butch Reynolds know that I have al commission, who confirmed the positive result. ■ Democrat incumbents were jubilant. supported." ways been one of the strongest proponents “On Oct. 24, the lAAF informed TAC of the result of IHanrlipalpr Reynolds and Randy Barnes, the world record-holder the second test and requested TAC to note the suspension in the shot put, were suspended by the International of random year-round drug testing. of the athlete in accordance with lAAF rule 59 and to ■ GOP saw little reason for rejoicing. Amateur Athletic Federation for testing positive for offer the athlete an opportunity of a hearing in accord steroids. “I have taken drug tests five times over ance with the rules and procedures of the lAAF. What's The lAAF, track and field’s world governing body, on the past 10 months. Believe me, the results ‘TAC confirmed that this has been done and the date ■ Herbst trounces Bunnell in 35th. -

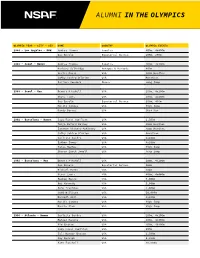

Alumni in the Olympics

ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS 1984 - Los Angeles - M&W Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m, 200m 1988 - Seoul - Women Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Barbara Selkridge Antigua & Barbuda 400m Leslie Maxie USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Juliana Yendork Ghana Long Jump 1988 - Seoul - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 200m, 400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Randy Barnes USA Shot Put 1992 - Barcelona - Women Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 1,500m Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeene Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Carlette Guidry USA 4x100m Esther Jones USA 4x100m Tanya Hughes USA High Jump Sharon Couch-Jewell USA Long Jump 1992 - Barcelona - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m Michael Bates USA 200m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Reuben Reina USA 5,000m Bob Kennedy USA 5,000m John Trautman USA 5,000m Todd Williams USA 10,000m Darnell Hall USA 4x400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Darrin Plab USA High Jump 1996 - Atlanta - Women Carlette Guidry USA 200m, 4x100m Maicel Malone USA 400m, 4x400m Kim Graham USA 400m, 4X400m Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 800m Juli Henner Benson USA 1,500m Amy Rudolph USA 5,000m Kate Fonshell USA 10,000m ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS Ann-Marie Letko USA Marathon Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeen Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Shana Williams -

The Future of Athlete Representation Within Governance Structures of National Sport Organizations

The Future of Athlete Representation within Governance Structures of National Sport Organizations The Association of Canada’s National Team Athletes © November 20, 2020 Published by AthletesCAN, the Association of Canada’s National Team Athletes. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form for commercial purposes, without the permission from AthletesCAN. Acknowledgements AthletesCAN extends their sincere appreciation to the members of the Leadership Committee for their important contributions and guidance throughout the development of the Athlete Representation Project. Ashley LaBrie Former Executive Director, AthletesCAN Patrick Jarvis Former Executive Director, Canada Snowboard Dasha Peregoudova Former President, AthletesCAN Jillian Drouin Former Vice-President, AthletesCAN Thea Culley Past Vice President, AthletesCAN Josh Vander Vies Former President, AthletesCAN We would like to sincerely thank those who contributed valuable insight in the development of the Athlete Representation Project at each phase outlined below. PHASE I 1. Canadian Athlete Representation Landscape Overview 2. Comprehensive Review of existing NSO bylaws 3. Identification of current models of athlete representation PHASE II 1. Athlete Representation Workshop & Panel hosted at the 2017 AthletesCAN Forum. PHASE III 1. NSO & Athlete Representative Consultation 2. Resource development 3. Final drafting phases of the position paper, “The Future of Athlete Representation in Canada”, including a comprehensive review of existing -

Deutsche Olympiasieger, Welt- Und Europameister (1896 - 2019)

Deutsche Olympiasieger, Welt- und Europameister (1896 - 2019) Summe 1896 bis 2019: 72 Olympiasiege 60 Weltmeistertitel 183 Europameistertitel vor 1945: 6 Olympiasiege 19 Europameistertitel 1949 - 1990: DLV: 14 Olympiasiege 3 Weltmeistertitel 35 Europameistertitel DVfL: 40 Olympiasiege 21 Weltmeistertitel 91 Europameistertitel 1991 - 2019: 12 Olympiasiege 38 Weltmeistertitel 44 Europameistertitel 1972 100m Hürd. Annelie Ehrhardt O l y m p i a s i e g e r 1972 4x100 m Krause, Mickler, Richter, Rosendahl 1928 800 m Lina Radke 1972 4x400 m Käsling, Kühne, Seidler, Zehrt 1936 Kugel Hans Woellke 1972 Hochsprung Ulrike Meyfarth 1936 Hammer Karl Hein 1972 Weitsprung Heide Rosendahl 1936 Speer Gerhard Stöck 1972 Speer Ruth Fuchs 1936 Diskus Gisela Mauermayer 1936 Speer Tilly Fleischer 1976 Marathon Waldemar Cierpinski 1976 Kugel Udo Beyer 1960 100 m Armin Hary 1976 100 m Annegret Richter 1960 4x100 m Cullmann, Hary, 1976 200 m Bärbel Wöckel Mahlendorf, Lauer 1976 100m Hürd. Johanna Schaller 1976 4x100 m Oelsner, Stecher, 1964 Zehnkampf Willi Holdorf Bodendorf, Wöckel 1964 80m Hürden Karin Balzer 1976 4x400 m Maletzki, Rohde, Streidt, Brehmer 1968 50km Gehen Christoph Höhne 1976 Hochsprung Rosemarie Ackermann 1968 Kugel Margitta Gummel 1976 Weitsprung Angela Voigt 1968 Fünfkampf Ingrid Mickler 1976 Diskus Evelin Jahl 1976 Speer Ruth Fuchs 1972 20km Gehen Peter Frenkel 1976 Fünfkampf Sigrun Siegl 1972 50km Gehen Bernd Kannenberg 1972 Stabhoch Wolfgang Nordwig 1980 Marathon Waldemar Cierpinski 1972 Speer Klaus Wolfermann 1980 50km Gehen Hartwig Gauder -

USA Basketball Men's Pan American Games Media Guide Table Of

2015 Men’s Pan American Games Team Training Camp Media Guide Colorado Springs, Colorado • July 7-12, 2015 2015 USA Men’s Pan American Games 2015 USA Men’s Pan American Games Team Training Schedule Team Training Camp Staffing Tuesday, July 7 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II 2015 USA Pan American Games Team Staff Head Coach: Mark Few, Gonzaga University July 8 Assistant Coach: Tad Boyle, University of Colorado 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Assistant Coach: Mike Brown 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Athletic Trainer: Rawley Klingsmith, University of Colorado Team Physician: Steve Foley, Samford Health July 9 8:30-10 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II 2015 USA Pan American Games 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Training Camp Court Coaches Jason Flanigan, Holmes Community College (Miss.) July 10 Ron Hunter, Georgia State University 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Mark Turgeon, University of Maryland 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II July 11 2015 USA Pan American Games 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Training Camp Support Staff 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Michael Brooks, University of Louisville July 12 Julian Mills, Colorado Springs, Colorado 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Will Thoni, Davidson College 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II USA Men’s Junior National Team Committee July 13 Chair: Jim Boeheim, Syracuse University NCAA Appointee: Bob McKillop, Davidson College 6-8 p.m. -

2030 Commonwealth Games Hosting Proposal – Part 1

Appendix B to Report PED18108(b) Page 1 of 157 2030 Commonwealth Games Hosting Proposal – Part 1 – October 23, 2019 – Appendix B to Report PED18108(b) Page 2 of 157 !"#"$%&''&()*+,-.$/+'*0$1$%+(23-45*$6+5-$7$1$&89:;<=$!#>$!"7?$ $ -C;D<$:G$%:A9<A9F$ $ $ #$ %&'"()*)+,"-+'"./0"!121"3450*" 7H7H 5<9I=AJAK$9:$9E<$6DC8<$)E<=<$39$+DD$L<KCAHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH M$ 7H!H ,<KC8N$:G$9E<$7?#"$L=J9JFE$*@OJ=<$/C@<FHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH P$ 7H#H +$%<A9<AC=N$%<D<;=C9J:A HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH Q$ 7HMH &I=$RJFJ:A$G:=$!"#" HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH ?$ 7HPH -=CAFG:=@JAK$&I=$%J9N HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7"$ 7HPH7 (<B$0O:=9$SC8JDJ9J<FHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7"$ 7HPH! LIJDTJAK$.C@JD9:AUF$0O:=9$-:I=JF@$%COC8J9N HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 77$ 7HPH# 2J=<89$*8:A:@J8$3@OC89 HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7!$ 7HPHM -=CT<$CAT$3AV<F9@<A9$&OO:=9IAJ9J<FHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7#$ 7HPHP +GG:=TC;D<$.:IFJAK HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7M$ 7HPHQ .C@JD9:AUF$0IF9CJAC;D<$SI9I=<$W$/=<<AJAK$9E<$/C@<FHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7M$ 7HPHX *AKCKJAK$R:DIA9<<=F -

Heel and Toe 2011/2012 Number 23

HEEL AND TOE ONLINE The official organ of the Victorian Race Walking Club 2011/2012 Number 23 6 March 2012 VRWC Preferred Supplier of Shoes, clothes and sporting accessories. Address: RUNNERS WORLD, 598 High Street, East Kew, Victoria (Melways 45 G4) Telephone: 03 9817 3503 Hours : Monday to Friday: 9:30am to 5:30pm Saturday: 9:00am to 3:00pm Website: http://www.runnersworld.com.au/ TIM'S WALKER OF THE WEEK Last week's Walker of the Week was Claire Tallent who took all before her in winning the Women's 20km championship in Hobart in an Olympic A qualifying time of 1:32:58. This was the only A qualifier done on the day in the horrendous conditions and it was her third win in a row in this annual championship. This confirmed her Olympic spot and was a dominant display. This week, I am going to balance the equation and announce my walker of the week as Jared Tallent. Jared and Claire flew out on the Sunday morning after their heroics in Hobart and both contested 20km races a week later in what was a big weekend carnival of walking in Chihuahua in Mexico – and both were successful, earning silvers in their respective events. Jared fought it out with Eder Sanchez of Mexico, taking silver in 1:21:50 while Claire fought it out with Portuguese walker Ines Henriques, also taking silver in 1:33:21. You can read about both their performances later in the newsletter. Jared and Claire with their second prize cheques in Chihuahua, along with Satoshi Yanagisawa (photo from Satoshi) MORE WALKERS ADDED TO THE AUSTRALIAN OLYMPIC TEAM With the Australian T&F Olympic Trials completed last weekend in Melbourne, Athletics Australia has now released the names of the next group of Olympic selections and the walkers are to the fore.