THE 2006 POTOMAC GORGE BIOBLITZ1 Overview and Results of a 30-Hour Rapid Biological Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R E P O R T S

I LLINOIS NATURAL HISTORY S U RVE Y R e p o r t s Winter 2006 No. 386 I N S I D E 24 Hours: The 2005 Busey Woods BioBlitz Mapping Owned, What brings more than 50 sci- systematics research of a poorly nearly 68% of the total number Managed, or Leased entists together with interested known family of fl ies (Therevi- of species identifi ed at Allerton? Properties of the Il- amateurs and the general public dae) that are not only present in Part of the answer goes to the linois Department of for a 24-hour extravaganza to Illinois, but found worldwide. root of why biodiversity studies Natural Resources see how many species could be The database was fi rst used at the are important and why so many 2 identifi ed from a 59-acre urban Allerton BioBlitz in 2001 where specialists are needed to do this natural area? The 2005 Busey 1,949 species were identifi ed work. Biologists working during New INHS Space Woods BioBlitz, which ran from nearly 3,000 observations the blitz were under no illusion Facilities from noon on June 24 to noon recorded during a 24-hour period that they would identify all of the 3 the following day, was species to be found in sponsored by the Urbana those 59 acres, and in (Illinois) Park District and fact, no one knew how Energy Impact of supported by a grant from many species might be Compact Development the Illinois Department there, because no one vs. Sprawl (Urban Ecology III) of Natural Resources. -

Backyard Bioblitz

Activity 1-3 Backyard BioBlitz You don’t have to travel to the rain forests of the Amazon or the coral reefs of Australia to discover biodiversity. Just AT A GLANCE Answer an ecoregional survey, then take a firsthand look at walk out the door, and you’ll find an amazing diversity biodiversity in your community. of life in backyards, vacant lots, streams and ponds, fields, gardens, roadsides and other natural and developed areas. OBJECTIVES In this activity, your students will have a chance to explore Name several native Illinois plants and animals and describe the diversity of life in their community. They’ll also get your local environment. Design and carry out a biological an introduction to how scientists size up the biodiversity inventory of a natural area. of an area—and why it’s so hard to count the species that live there. SUBJECTS English language arts, science BEFORE YOU BEGIN! PART I SKILLS You will need to gather field guides and other resources gathering (collecting, observing, researching), organizing about your area. To best prepare your students for this (classifying), analyzing (discussing, questioning) activity, acquire resources in advance. Suggested Illinois resources can be found in the “Resources” list with this LINKS TO ILLINOIS BIODIVERSITY BASICS activity (page 36). You can use the “Ecoregional Survey” CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK as it is written, or you can adapt it more specifically to species diversity your area and situation. You’ll need a copy for each VOCABULARY student, plus one copy for each team of four to five ecoregion, gall, ground-truthing, migration, native species, students. -

Taconic State Park Bioblitz, May 2013

Taconic State Park BioBlitz May 4-5, 2013 On May 4, 2013, 32 scientific professionals gathered at Taconic State Park in Copake Falls, NY for a BioBlitz, a 24-hour inventory of the park’s biodiversity. Our objectives were to look for rare species and significant natural communities in the park and document as many of the animals and plants living there as possible. This was a collaborative effort between the NY Natural Heritage Program (NYNHP) of the State University of NY College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY ESF); the Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation (State Parks); and Parks & Trails New York, who enlisted the help of scientists from various agencies, Some Taconic State Park BioBlitz participants, by organizations, and universities. Participants included Shereen Brock biologists with varying expertise and affiliations including NYNHP, State Parks, NYS DEC, Audubon, SUNY Plattsburgh, NYS Museum, Lloyd Center for Environmental Studies, Carnegie Museum, among others. At least 11 different organizations were represented and participants from 4 states assisted in the effort. Throughout the 24-hour period (9am Saturday May 4th to 9am the following morning), scientists formed small teams across affiliations and taxonomic expertise, targeting exemplary habitats in different areas of the park that could harbor rare species and high biodiversity. Teams visited forests and summits on Sunset Conrad Vispo, Hawthorne Valley Farm Rock, and Alander, Brace and Cedar Mountains. We also surveyed by George Heitzman Rudd Pond, wetlands and ponds near Mount Riga, Preachy Hollow, and Weed Mines, and several brooks throughout the park including Bash Bish and Cedar Brook, and Noster Kill. -

Call to Action #7 - Profiles in Partnering

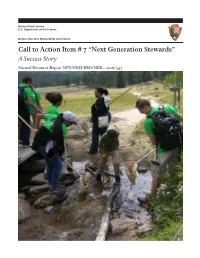

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Call to Action Item # 7 “Next Generation Stewards” A Success Story Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/BRD/NRR—2016/1357 ON THE COVER Aquatic macroinvertebrate inventory at Rocky Mountain National Park during 2012 NPS/National Geographic Society Rocky Mountain BioBlitz. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service Call to Action Item # 7 “Next Generation Stewards” A Success Story Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/BRD/NRR—2016/1357 Edited by: Sally Plumb Biodiversity Coordinator Biological Resources Division 1201 Oakridge Drive, Suite 200 Fort Collins, Colorado 80525 December, 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and oth- ers in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision- making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the in- tended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

The OMG! the Outdoor Meeting Guide

The O.M.G! The Outdoor Meeting Guide ❧ ❧ Your guide to taking your meetings outside Take It Outside! Looking to take your meetings safely outside but not ready to start an outdoor badge? Or maybe you have already done some of them? This guide will help you get outside with minimal planning and supplies. Find an example of your typical Girl Scout meeting here. Adjust the time if or where needed. Pick from the attached activities. Parts of a Estimated Details of time block Meeting Time See examples outlined in this guide. Start Up 5-10 Some prep work for outdoor meeting Activity minutes ideas can be used as part of the start - up activity as well. 5 Opening Flag Ceremony, Promise & Law Minutes 5 Business Announcements, Dues, Kapers Minutes Pick one of the attached activities. The activities range from an estimate of 20-45 minutes, times can be adjusted based on your troop size, girls’ experience levels, and the time 20-45 Activity allowed for other meeting activities Minutes (i.e. opening, business). For example, if you know your girls like to put a lot of detail in their designing, you may want to calculate that into what best fits your group for these activities. Everyone checks for litter and makes ❧ 5 the space look better than we found Clean Up Minutes it. Put things back where they were found. Closing 5 Minutes Socially Distanced Friendship Circle Things to keep in mind while meeting outside Depending what time of year it is, many factors may affect your outdoor meetings. -

Miscellanea 47

MISCELLANEA 47 Miscellanea Reviews preparation. Champion tree hunter Byron Carmean is recognized for his efforts in Virginia. Featured old trees Remarkable Trees of Virginia, by Nancy Ross Hugo & include stunted red cedars on limestone cliffs along the Jeff Kirwan; photography by Robert Llewellyn. 2008. New River in Giles County that are more than 450 Albemarle Books, Earlysville, VA (distributed by years old (see also Larson, 1997) and huge bald University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville). 206 pp., cypresses along the Blackwater River in Southampton 30 x 28 cm, ca. 160 color photographs (plus six black County that exceed 800 years old. Historic trees include and white). ISBN 978-0-9742707-2-2 (cloth; $49.95). a tulip poplar planted by Thomas Jefferson in 1807 at Monticello and several trees with connections to Civil This large coffee table book features well-written War sites or slavery. Unique trees include hollow, narratives and stunning color photographs of more than bizarre-shaped water tupelos and a massive sycamore 100 of the most “remarkable” trees found in Virginia. leaning at a 45o angle with no signs of falling over. As noted by the authors, about 20 of these trees would The authors discuss many interesting topics in their appear on virtually anyone’s list of the 100 most narratives about specific trees. For example, they remarkable trees in the state. Their task was to sift lament the loss of the once-dominant American through more than 1,000 nominations provided by the chestnut and briefly describe current efforts aimed at general public, as well as other trees identified by their trying to restore this species. -

The Great Swamp Watershed Association ACROSS the WATERSHED Fall-Winter 2011

The Great Swamp Watershed Association ACROSS THE WATERSHED Fall-Winter 2011 Protecting our Waters and our Land for 30 Years New Jersey’s Great Swamp: A Tradition of Community Involvement ith our 30th Anniversary Gala officially formed. What we discovered can only right around the corner, Steve be described as a long tradition of environ Reynolds, our new Director of mental education, advocacy, and stewardship WCommunications & Membership, decided sup ported by communities throughout our to look back through the organ ization’s water shed. We hope you enjoy browsing photo archives to learn some more about these images as much as we did, and we hope where we have been. Our col lection stretches you feel the same kind of pride we do in the back into the 1960s, almost 20 years before remarkable accomplishments achieved in the Great Swamp Watershed Association was the name of the Great Swamp. Environmental Education in Great Swamp, 1967—present (1) Great Swamp tour, Nature Trail Area, Oct. 21, 1967. (2) Classroom teaching with middle school students using a GSWA watershed model, 1999. (3) Students learn about water quality in the field, 1986. (4) Current Director of Education & Outreach Hazel England demonstrates watershed dynamics to elementary school children—yes, that’s the same model from 1999! (5) Information abounds on this guided tour of Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge (GSNWR) in 1996. (6) A bird-watching tour learns from birding expert Emile DeVito at GSWA’s 2011 BioBlitz. Environmental Stewardship in Great Swamp, 1973—present (1) A perspective on Millington Gorge and water macroinvertebrate surveying, 1999. -

Public Engagement and Wildlife Recording Events in the UK Matt Postles & Madeleine Bartlett, Bristol Natural History Consortium

- DRAFT - The rise and rise of BioBlitz: public engagement and wildlife recording events in the UK Matt Postles & Madeleine Bartlett, Bristol Natural History Consortium Abstract A BioBlitz is a collaborative race against the clock to discover as many species of plants, animals and fungi as possible, within a set location, over a defined time period - usually 24 hours. A BioBlitz usually combines the collection of biological records with public engagement as experienced naturalists and scientists explore an area with members of the public, volunteers and school groups. The number of BioBlitz events taking place in the UK has increased explosively since the initiation of the National BioBlitz programme in 2009 attracting large numbers of people to take part and gathering a large amount of biological data. BioBlitz events are organised with diverse but not mutually exclusive aims and objectives and the majority of events are considered successful in meeting those aims. BioBlitz events can cater for and attract a wide diversity of participants through targeted activities, particularly in terms of age range, and (in the UK) have engaged an estimated 2,250 people with little or no prior knowledge of nature conservation in 2013. BioBlitz events have not been able to replicate that success in terms of attracting participants from ethnic minority groups. Key positive outcomes for BioBlitz participants identified in this study include enjoyment, knowledge and skills based learning opportunities, social and professional networking opportunities and inspiring positive action Whilst we know that these events generate a lot of biological records, the value of that data to the end user is difficult to quantify with the current structure of local and national recording schemes. -

Berkshire Bioblitz 2010 Report

Groupings of Organisms & Key Experts 2010 Berkshire BioBlitz, Pittsfield State Forest, June 4 & 5, 2010 Compiled & Reported by Scott LaGreca Lisa Provencher, Dan Shustack, Jeremy Smith, Mike Gramacki, Lauren Moffat, and Scott LaGreca ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Before listing the nearly 1,000 species discovered at Pittsfield State Forest, acknowledgements must be given. The 2010 Berkshire BioBlitz—the very first, large all- species biological inventory in Berkshire County, Massachusetts—would not have been possible without the help of many organizations and individuals. First and foremost, Lisa Provencher of the MCLA STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering & Math) team deserves full credit as co-organizer of the BioBlitz. Not only did she advise and assist with every aspect of the scientific survey, she also single-handedly developed the education component of the Blitz for area schoolchildren. The Berkshire Museum confidently led our group of partner organizations and made the BioBlitz a success; Executive Director Stuart Chase and Director of Interpretation Maria Mingalone are especially thanked for always believing in the power of hands-on, experiential natural science education. Jane Winn of BEAT (Berkshire Environmental Action Team) was our “go-to girl”, ably assisting with all aspects of the Blitz—and sounding the horn which officially kicked off the Blitz at noon on Friday. We are also grateful to BioBlitz partner organization Massachusetts DCR (Department of Conservation and Recreation), on whose property the BioBlitz took place. Mark Todd (Supervisor of Pittsfield State Forest), Scott Dean, Chris Hookie, and Bob Mellace provided critical advice and logistical support. In addition, Keith Babuszczak generously cooked an early breakfast for over a dozen hungry staff and scientists on Saturday morning! Peter Alden (Walden Biodiversity Day/ The Walden Woods Project) is warmly thanked for giving me advice regarding running a BioBlitz, and for providing the template for this report. -

Glenn Oakes Bioblitz Report

Glen Oakes BioBlitz Report Note: The black line in the map denotes Glen Oakes Town Forest in Fremont, N.H. From May, 2011 Glenn Oakes Bioblitz 2011 page 2 of 11 whk Introduction On and around the weekend of May 21, 2011, an intensive species inventory (BioBlitz) was made in Fremont, NH within the Glen Oakes Town Forest. The event was organized to enhance the baseline information of the biodiversity found in this area begun by Forester Charles A. Moreno. Three small teams of volunteers lead by experts spent the morning of Saturday, May 21, 2011 scouring the Glen Oakes Town Forest in three different directions keeping an inventory of the species they identified. In addition, other volunteers unable to attend the event that day reported their findings from the week before and after the event. The result of these efforts is the species inventory list found in the right-hand column (verified 5/2011) of this report. The third column from the left contains observations made by Charles A. Moreno during the period of time he was working on the Forest Management Plan for the Glen Oakes Conservation Area (2009). Together the two columns represent the observed biodiversity of this area This conservation area, a part of the larger Spruce Swamp ecosystem, provides a unique haven of biodiversity. Much of the area inventoried has been identified as “highest quality habitat” or as important “supporting habitat” in the New Hampshire Wildlife Action Plan – please see the map printed on the cover of this report. It is worth noting the area contains the critical habitats required for several Species of Greatest Conservation Concern in New Hampshire. -

Schoolyard Bioblitz Education Kit

Schoolyard Bioblitz Education Kit For Grades 9-12 2 BIOBLITZ – GRADES 9-12 Contents Introduction to the Schoolyard Bioblitz Education Kit ...................................................................3 About the Kit ..........................................................................................................................................3 About Nature NB ...................................................................................................................................3 Acknowledgements .........................................................................................................................3, 50 SECTION 1: Introducing concepts ..............................................................................................4 1.1: What is Biodiversity? ..............................................................................................................4 1.2: Why is Biodiversity important? ............................................................................................4 1.3: What is a Bioblitz? ..................................................................................................................5 1.4: Biodiversity in New Brunswick ............................................................................................5 1.5: Activity 1: The Wheel of Life ..............................................................................................10 SECTION 2: Watching the Documentary Film ......................................................................14 -

Tardigrades: an Imaging Approach, a Record of Occurrence, and A

TARDIGRADES: AN IMAGING APPROACH, A RECORD OF OCCURRENCE, AND A BIODIVERSITY INVENTORY By STEVEN LOUIS SCHULZE A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Science Graduate Program in Biology Written under the direction of Dr. John Dighton And approved by ____________________________ Dr. John Dighton ____________________________ Dr. William Saidel ____________________________ Dr. Emma Perry ____________________________ Dr. Jennifer Oberle Camden, New Jersey May 2020 THESIS ABSTRACT Tardigrades: An Imaging Approach, A Record of Occurrence, and a Biodiversity Inventory by STEVEN LOUIS SCHULZE Thesis Director: Dr. John Dighton Three unrelated studies that address several aspects of the biology of tardigrades— morphology, records of occurrence, and local biodiversity—are herein described. Chapter 1 is a collaborative effort and meant to provide supplementary scanning electron micrographs for a forthcoming description of a genus of tardigrade. Three micrographs illustrate the structures that will be used to distinguish this genus from its confamilials. An In toto lateral view presents the external structures relative to one another. A second micrograph shows a dentate collar at the distal end of each of the fourth pair of legs, a posterior sensory organ (cirrus E), basal spurs at the base of two of four claws on each leg, and a ventral plate. The third micrograph illustrates an appendage on the second leg (p2) of the animal and a lateral appendage (C′) at the posterior sinistral margin of the first paired plate (II). This image also reveals patterning on the plate margin and the leg.