Connecticut's Fourth Congressional District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Sciences Alumni

Health Sciences Alumni Updated: 11/15/17 Allison Stickney 2018 High school science teaching Teach for America, Dallas-Fort Worth Sophia Sugar 2018 Research Assistant Nationwide Children’s Hosp., Columbus, OH Wanying Zhang 2017 Accelerated BSN, Nursing MGH Institute for Health Professions Kelly Ashnault 2017 Pharmacy Technician CVS Health Ian Grape 2017 Middle School Science Teacher Teach Kentucky Madeline Hobbs 2017 Medical Assistant Frederick Foot & Ankle, Urbana, MD Ryan Kennelly 2017 Physical Therapy Aide Professional Physical Therapy, Ridgewood, NJ Leah Pinckney 2017 Research Assistant UConn Health Keenan Siciliano 2017 Associate Lab Manager Medrobotics Corporation, Raynham, MA Ari Snaevarsson 2017 Nutrition Coach True Fitness & Nutrition, McLean VA Ellis Bloom 2017 Pre-medical fellowship Cumberland Valley Retina Consultants Elizabeth Broske 2017 AmeriCorps St. Bernard Project, New Orleans, LA Ben Crookshank 2017 Medical School Penn State College of Medicine Veronica Bridges 2017 Athletic Training UT Chattanooga, Texas A&M, Seton Hall Samantha Day 2017 Medical School University of Maryland School of Medicine Alexandra Fraley 2017 Epidemiology Research Assistant Department of Health and Human Services Genie Lavanant 2017 Athletic Training Seton Hall University Taylor Tims 2017 Nursing Drexel University, Johns Hopkins University Chase Stopyra 2017 Physical Therapy Rutgers School of Health Professions Madison Tulp 2017 Special education Teach for America Joe Vegso 2017 Nursing UPenn, Villanova University Nicholas DellaVecchia 2017 Physical -

Nominations Of: Ronald Sims, Fred P. Hochberg, Helen R

S. HRG. 111–173 NOMINATIONS OF: RONALD SIMS, FRED P. HOCHBERG, HELEN R. KANOVSKY, DAVID H. STEVENS, PETER KOVAR, JOHN D. TRASVIN˜A, AND DAVID S. COHEN HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON NOMINATIONS OF: RONALD SIMS, OF WASHINGTON, TO BE DEPUTY SECRETARY, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT FRED P. HOCHBERG, OF NEW YORK, TO BE PRESIDENT AND CHAIRMAN, EXPORT-IMPORT BANK HELEN R. KANOVSKY, OF MARYLAND, TO BE GENERAL COUNSEL, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT DAVID H. STEVENS, OF VIRGINIA, TO BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR HOUSING–FEDERAL HOUSING COMMISSIONER, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT PETER KOVAR, OF MARYLAND, TO BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR CONGRESSIONAL AND INTERGOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT JOHN D. TRASVIN˜ A, OF CALIFORNIA, TO BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR FAIR HOUSING AND EQUAL OPPORTUNITY, DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT DAVID S. COHEN, OF MARYLAND, TO BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR TERRORIST FINANCING, DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY APRIL 23, 2009 Printed for the use of the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs ( Available at: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate/senate05sh.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 53–677 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut, Chairman TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota RICHARD C. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions Of

April 10, 2003 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E725 have tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans united support in improving the safety and many of us in this country and sparked an than veterans benefits. Period. No other expla- welfare of our children. We cannot allow our emotional response from literally thousands of nation is plausible. It is almost impossible for law enforcement to lose step with an ever- people in all 50 states, including many of the me to believe that as the veterans population evolving electronic society. We cannot allow men and women who proudly wear the uni- rises and ages, that this House would elimi- these sexual predators to get away with the form of our military in defense of this great nate benefits. criminal acts they are committing against inno- country. Mr. Speaker, we have men and women on cent children. We cannot allow one of our Unlike so many of the speeches we hear in the field of battle in Iraq, fighting to make oth- greatest advancements to become a tool for this city, Beth Chapman’s remarks were not ers free. Should we not honor their sacrifice our biggest degenerates. The Cybermolester made with a particular slant that was either by keeping our promises to those that have al- Enforcement Act will ensure that these pro-Democrat or pro-Republican. Instead, ready served? Should we not eliminate these ‘‘cyberpredators’’ are suitably punished and Beth’s comments were simply ‘‘pro-American,’’ cuts in VA spending? The wealthy need a tax America’s children are properly protected. -

("DSCC") Files This Complaint Seeking an Immediate Investigation by the 7

COMPLAINT BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION CBHMISSIOAl INTRODUCTXON - 1 The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee ("DSCC") 7-_. J _j. c files this complaint seeking an immediate investigation by the 7 c; a > Federal Election Commission into the illegal spending A* practices of the National Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee (WRSCIt). As the public record shows, and an investigation will confirm, the NRSC and a series of ostensibly nonprofit, nonpartisan groups have undertaken a significant and sustained effort to funnel "soft money101 into federal elections in violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended or "the Act"), 2 U.S.C. 5s 431 et seq., and the Federal Election Commission (peFECt)Regulations, 11 C.F.R. 85 100.1 & sea. 'The term "aoft money" as ueed in this Complaint means funds,that would not be lawful for use in connection with any federal election (e.g., corporate or labor organization treasury funds, contributions in excess of the relevant contribution limit for federal elections). THE FACTS IN TBIS CABE On November 24, 1992, the state of Georgia held a unique runoff election for the office of United States Senator. Georgia law provided for a runoff if no candidate in the regularly scheduled November 3 general election received in excess of 50 percent of the vote. The 1992 runoff in Georg a was a hotly contested race between the Democratic incumbent Wyche Fowler, and his Republican opponent, Paul Coverdell. The Republicans presented this election as a %ust-win81 election. Exhibit 1. The Republicans were so intent on victory that Senator Dole announced he was willing to give up his seat on the Senate Agriculture Committee for Coverdell, if necessary. -

Www. George Wbush.Com

Post Office Box 10648 Arlington, VA 2221 0 Phone. 703-647-2700 Fax: 703-647-2993 www. George WBush.com October 27,2004 , . a VIA FACSIMILE (202-219-3923) AND CERTIFIED MAIL == c3 F Federal Election Commission 999 E Street NW Washington, DC 20463 b ATTN: Office of General Counsel e r\, Re: MUR3525 Dear Federal Election Commission: On behalf of President George W. Bush and Vice President Richard B. Cheney as candidates for federal office, Karl Rove, David Herndon and Bush-Cheney ’04, Inc., this letter responds to the allegations contained in the complaint filed with the Federal Election Commission (the “Commission”) by Kerry-Edwards 2004, Inc. The Kerry Campaign’s complaint alleges that Bush-Cheney 2004 and fourteen other individuals and organizations violated the Federal Election Campaign Act of 197 1, as amended (2 U.S.C. $ 431 et seq.) (“the Act”). Specifically, the Kerry Campaign alleges that individuals and organizations named in the complaint illegally coordinated with one another to produce and air advertising about Senator. Kerry’s military service. 1 Considering that no entity by the name of Bush-Cheney 2004 appears to exist, 1’ Bush-Cheney ’04, Inc. (“Bush Campaign”) presumes that the Kerry Campaign mistakenly filed its complaint against a non-existent entity and actually intended to file against the Bush Campaign. Assuming that the foregoing presumption is correct; the Bush Campaign, on behalf of itself and President George W. Bush, Vice President Richard B. Cheney, Karl Rove, David Herndon (the “Parties”), responds as follows: Response to Allegations Against President George W. Bush, Vice President Richard B. -

Going Nuts in the Nutmeg State?

Going Nuts in the Nutmeg State? A Thesis Presented to The Division of History and Social Sciences Reed College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts Daniel Krantz Toffey May 2007 Approved for the Division (Political Science) Paul Gronke Acknowledgements Acknowledgements make me a bit uneasy, considering that nothing is done in isolation, and that there are no doubt dozens—perhaps hundreds—of people responsible for instilling within me the capability and fortitude to complete this thesis. Nonetheless, there are a few people that stand out as having a direct and substantial impact, and those few deserve to be acknowledged. First and foremost, I thank my parents for giving me the incredible opportunity to attend Reed, even in the face of staggering tuition, and an uncertain future—your generosity knows no bounds (I think this thesis comes out to about $1,000 a page.) I’d also like to thank my academic and thesis advisor, Paul Gronke, for orienting me towards new horizons of academic inquiry, and for the occasional swift kick in the pants when I needed it. In addition, my first reader, Tamara Metz was responsible for pulling my head out of the data, and helping me to consider the “big picture” of what I was attempting to accomplish. I also owe a debt of gratitude to the Charles McKinley Fund for providing access to the Cooperative Congressional Elections Study, which added considerable depth to my analyses, and to the Fautz-Ducey Public Policy fellowship, which made possible the opportunity that inspired this work. -

Chairman Rogers, Ranking Member Lowey, Members of the Committee

TESTIMONY OF REPRESENTATIVE JOSEPH P. KENNEDY, III (MA-04) SUBCOMMITTEE ON STATE, FOREIGN OPERATIONS AND RELATED PROGRAMS HOUSE APPROPRIATIONS MEMBER DAY HEARING MARCH 16, 2017 Chairman Rogers, Ranking Member Lowey, Members of the Committee: Thank you for convening this hearing today to discuss the resources that are vital for protecting America’s security, safeguarding our core values of democracy and human rights, and continuing America’s leadership across the world. As America and the world face unprecedented obstacles and instability, but also opportunities, your work has never been more important. Today I want to speak to you about the urgent need for an expanded Peace Corps. Some 7,200 Peace Corps Volunteers currently serve in 63 countries, training communities in critical areas of need, including food security, combating HIV/AIDS, and facilitating girls and women’s empowerment through education and economic independence. Through partnerships with PEPFAR, Feed the Future and the President’s Malaria Initiative, Volunteers provide crucial assistance to efforts to fight against HIV/AIDS, promote sustainable methods for food security, and eliminate malaria. The Peace Corps is also recognized for its indispensable role in national security. As 121 retired three and four-star generals recently wrote to Congressional leadership, “Peace Corps and other development agencies are critical to preventing conflict and reducing the need to put our men and women in uniform in harm’s way.” The Peace Corps’ cost-efficient, effective model is reflected -

Chris Dodd for President

Speech to the 2007 DNC Winter Meeting | Chris Dodd for President http://chrisdodd.com/2007_DNC_Speech Chris Dodd for President Speech to the 2007 DNC Winter Meeting Thank you very, very much. What a great, great crowd. Good to see Democrats here in Washington. Give yourself a good round of applause. Let me begin by thanking those wonderful folks from Connecticut and elsewhere. I want to thank Nancy DiNardo, our state chair, and others who have come here today to be a part of this great effort. Howard, I want to thank you, as well, for your tremendous work. Mark, thank you for that very generous introduction. I always find, sometimes, the introductions go on longer than my remarks, from time to time in these matters. I was thinking, as Mark was going through the introduction, I come from a rather large family. I'm one of six children. And one of my older sisters introduced me -- or was present, rather, at an event where I was introduced a few months ago. And the master of ceremonies, not unlike Mark, went on at some length, and concluded the introduction by saying, "It now gives me a great deal of pleasure to present to you not only a great senator from Connecticut but one of the great leaders of the Western world." Well, you can imagine -- I'm there with my sister in the audience -- how much I appreciated those kind remarks. That evening, we're driving back to Providence, Rhode Island, where she lives. And during one of those quiet moments in the car, I turn to my sister, Martha, and I said, "Martha, how many great leaders of the Western world do you think there are?" Only as an older sister could do, she said, "One less than you think. -

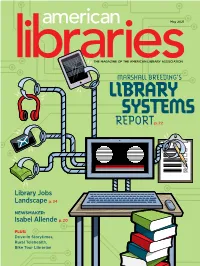

Download on the AASL Website an Anonymous Funder Donated $170,000 Tee, and the Rainbow Round Table at Bit.Ly/AASL-Statements

May 2021 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION MARSHALL BREEDING’S LIBRARY SYSTEMS REPORTp. 22 Library Jobs Landscape p. 34 NEWSMAKER: Isabel Allende p. 20 PLUS: Drive-In Storytimes, Rural Telehealth, Bike Tour Librarian This Summer! Join us online at the event created and curated for the library community. Event Highlights • Educational programming • COVID-19 information for libraries • News You Can Use sessions highlighting • Interactive Discussion Groups new research and advances in libraries • Presidents' Programs • Memorable and inspiring featured authors • Livestreamed and on-demand sessions and celebrity speakers • Networking opportunities to share and The Library Marketplace with more than • connect with peers 250 exhibitors, Presentation Stages, Swag-A-Palooza, and more • Event content access for a full year ALA Members who have been recently furloughed, REGISTER TODAY laid o, or are experiencing a reduction of paid alaannual.org work hours are invited to register at no cost. #alaac21 Thank you to our Sponsors May 2021 American Libraries | Volume 52 #5 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 2021 LIBRARY SYSTEMS REPORT Advancing library technologies in challenging times | p. 22 BY Marshall Breeding FEATURES 38 JOBS REPORT 34 The Library Employment Landscape Job seekers navigate uncertain terrain BY Anne Ford 38 The Virtual Job Hunt Here’s how to stand out, both as an applicant and an employer BY Claire Zulkey 42 Serving the Community at All Times Cultural inclusivity programming during a pandemic BY Nicanor Diaz, Virginia Vassar -

Candidates, Campaigns, and Political Tides: Electoral Success in Colorado's 4Th District Megan Gwynne Maccoll Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2012 Candidates, Campaigns, and Political Tides: Electoral Success in Colorado's 4th District Megan Gwynne MacColl Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation MacColl, Megan Gwynne, "Candidates, Campaigns, and Political Tides: Electoral Success in Colorado's 4th District" (2012). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 450. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/450 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE CANDIDATES, CAMPAIGNS, AND POLITICAL TIDES: ELECTORAL SUCCESS IN COLORADO’S 4TH DISTRICT SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR JON SHIELDS AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY MEGAN GWYNNE MacCOLL FOR SENIOR THESIS SPRING/2012 APRIL 23, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………...…..1 Chapter One: The Congresswoman as Representative……………………………………4 Chapter Two: The Candidate as Political Maestro………………………………………19 Chapter Three: The Election as Referendum on National Politics....................................34 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….47 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..49 INTRODUCTION The 2010 congressional race in Colorado’s 4th District became political theater for national consumption. The race between two attractive, respected, and qualified candidates was something of an oddity in the often dysfunctional 2010 campaign cycle. Staged on the battleground of a competitive district in an electorally relevant swing state, the race between Republican Cory Gardner and Democratic incumbent Betsy Markey was a partisan fight for political momentum. The Democratic Party made inroads in the 4th District by winning the congressional seat in 2008 for the first time since the 1970s. Rep. Markey’s win over Republican incumbent Marilyn Musgrave was supposed to signal the long-awaited arrival of progressive politics in the district, after Rep. -

Haworthpeter.Pdf (1.4MB)

Community and Federalism in the American Political Tradition A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Peter Daniel Haworth, M.A. Washington, D.C. December 11, 2008 Community and Federalism in the American Political Tradition Peter Daniel Haworth, M.A. Thesis Advisor: George W. Carey, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Aside from the various minor issues, there are two major questions that are addressed in this dissertation: (1) Can socially cohesive community be attributed to the local and/or federal levels of the American system in the colonial and founding periods? (2) How has the political centralization of the twentieth century affected socially cohesive community and public policy for “sensitive” issues, which require such cohesion to become settled? The author attempts to answer these questions via articulating and defending the following thesis: Socially cohesive community (i.e., a mode of intrinsically valuable friendship community that can develop around shared thick-level values and that is often associated with political activity and local interaction) was a possibility for local- level communities during the colonial and founding periods of American history; whereas, when the colonies/States were grouped together as an aggregate union, they did not constitute a true nation or single community of individuals. Hence, such “union” lacked a common good (and, a fortiori , it lacked a thick-level common good necessary for social cohesion). Through the course of American history, the political system has been centralized or transformed from a federal system into a de facto unitary system, and this change has undermined the possibility of social cohesion at the local level. -

Downtown Darien CT

DOWNTOWN DARIEN An Action Plan for the Revitalization of Downtown Darien Connecticut Main Street Center Resource Team May 22 – 25, 2006 Darien Revitalization Inc. 30 Old Kings Highway South Darien, CT 06820 203-655-7557 [email protected] Made possible by: Connecticut Main Street Center PO Box 261595 Hartford, CT 06126 860-280-2337 www.ctmainstreet.org May 2006 2 DOWNTOWN DARIEN An Action Plan for the Revitalization of Downtown Darien May 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents....................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose...................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 4 Next Steps ................................................................................................................................. 4 Darien Revitalization Inc. Mission, Vision and Goals .................................................................. 5 List of Participants...................................................................................................................... 6 Overview.................................................................................................................................... 8 Design.....................................................................................................................................