The United States and Japan in Global Context: 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GJAA Nishimura.Pdf (936Kb)

Nishimura | Chasing the Conservative Dream Research Chasing the Conservative Dream: Why Shinzo Abe Failed to Revise the Constitution of Japan Rintaro Nishimura This paper examines the role of domestic actors in shaping Japan’s constitutional debate during Shinzo Abe’s time as prime minister. Based on a holistic analysis of the prevailing literature and the role of the public, leadership, and other political actors, this study finds that Abe was unable to garner enough support from the public or fellow lawmakers to push his version of proposed revisions to the Constitution of Japan. The paper identifies the wide spectrum of views that exist on the issue and how revising the constitution is viewed as a challenge against prevailing norms. Public opinion remains opposed to revision and the inability of lawmakers to build consensus on what to amend stymies the process further. Abe seems to have had a grasp on the political climate, opting to pursue constitutional revision largely for electoral purposes. Introduction Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced his decision to step down in August 2020.1 Japan’s longest-serving prime minister left behind a mixed legacy defined by electoral and foreign policy achievements, as well as a period of economic stagnation and string of political scandals.2 But what best defines Abe’s political career will undoubtedly be his desire, and ultimate failure, to revise the seventy-four-year-old Constitution of Japan (COJ). Although Abe’s failure to amend the COJ is often attributed to institutional hurdles, this paper argues that varying interests among domestic actors—from public resistance to militarism, to the prime minister’s agenda, and lawmakers’ scattered inter- ests regarding what exactly to amend—ultimately determined the fate of his political 1 Eric Johnston and Satoshi Sugiyama, “Abe to resign over health, ending era of political stability,” Japan Times, August 28, 2020, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/08/28/national/politics-di- plomacy/shinzo-abe-resign/. -

2013-JCIE-Annual-Report.Pdf

Table of Contents 2011–2013 in Retrospect .................................................................................................................................3 Remembering Tadashi Yamamoto ............................................................................................................6 JCIE Activities: April 2011–March 2013 ........................................................................................................9 Global ThinkNet 13 Policy Studies and Dialogue .................................................................................................................... 14 Strengthening Nongovernmental Contributions to Regional Security Cooperation The Vacuum of Political Leadership in Japan and Its Future Trajectory ASEAN-Japan Strategic Partnership and Regional Community Building An Enhanced Agenda for US-Japan Partnership East Asia Insights Forums for Policy Discussion ........................................................................................................................ 19 Trilateral Commission UK-Japan 21st Century Group Japanese-German Forum Korea-Japan Forum Preparing Future Leaders .............................................................................................................................. 23 Azabu Tanaka Juku Seminar Series for Emerging Leaders Facilitation for the Jefferson Fellowship Program Political Exchange Programs 25 US-Japan Parliamentary Exchange Program ......................................................................................26 -

Boston Red Sox 5, New York Yankees 3

WORLD SERIES CHAMPIONS (9): 1903, 1912, 1915, 1916, 1918, 2004, 2007, 2013, 2018 AMERICAN LEAGUE CHAMPIONS (14): 1903, 1904, 1912, 1915, 1916, 1918, 1946, 1967, 1975, 1986, 2004, 2007, 2013, 2018 AMERICAN LEAGUE EAST DIVISION CHAMPIONS (10): 1975, 1986, 1988, 1990, 1995, 2007, 2013, 2016, 2017, 2018 AMERICAN LEAGUE WILD CARD (7): 1998, 1999, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2008, 2009 @BOSTONREDSOXPR • HTTP://PRESSROOM.REDSOX.COM • @SOXNOTES BOSTON RED SOX 5, NEW YORK YANKEES 3 Friday, June 25, 2021 • Fenway Park, Boston, MA 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 R H E PITCH COUNTS New York 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 9 2 RED SOX Boston 3 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 X 5 7 1 Pitcher # (Strikes) Win: Whitlock (3-1) Loss: Germán (4-5) Save: Barnes (16) Martín Pérez 67 (44) Time of Game: 3:37 Attendance: 36,869 (1st sellout) Weather: 66°, E at 6 mph Hirokazu Sawamura 20 (10) Yankees HR: None Garrett Whitlock 33 (21) Adam Ottavino 13 (10) Red Sox HR: None Matt Barnes 19 (14) YANKEES RED SOX NOTES (45-31) Pitcher # (Strikes) Domingo Germán 72 (46) THE RED SOX are 4-0 vs. NYY this season, out-scoring the Yankees, 23-13, during the season series. Lucas Luetge 40 (19) Jonathan Loaisiga 21 (15) Are 3-4 in their last 7 games, but 13-8 in their last 21...Are 21-14 at home since getting swept by BAL to begin the season. Zack Britton 11 (7) 4 Sox relievers combined to toss 5.1 scoreless innings: Sawamura (1.1 IP), Whitlock (2.0), Ottavino (1.0), and Barnes (1.0). -

Atlanta Braves 3, Boston Red Sox 1

WORLD SERIES CHAMPIONS (9): 1903, 1912, 1915, 1916, 1918, 2004, 2007, 2013, 2018 AMERICAN LEAGUE CHAMPIONS (14): 1903, 1904, 1912, 1915, 1916, 1918, 1946, 1967, 1975, 1986, 2004, 2007, 2013, 2018 AMERICAN LEAGUE EAST DIVISION CHAMPIONS (10): 1975, 1986, 1988, 1990, 1995, 2007, 2013, 2016, 2017, 2018 AMERICAN LEAGUE WILD CARD (7): 1998, 1999, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2008, 2009 @BOSTONREDSOXPR • HTTP://PRESSROOM.REDSOX.COM • @SOXNOTES ATLANTA BRAVES 3, BOSTON RED SOX 1 Tuesday, May 25, 2021 • Fenway Park, Boston, MA 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 R H E PITCH COUNTS Atlanta 0 0 2 0 0 1 0 0 0 3 8 1 RED SOX Boston 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 3 0 Pitcher # (Strikes) Win: Morton (3-2) Loss: Richards (4-3) Save: Smith (8) Garrett Richards 97 (59) Time of Game: 3:06 Attendance: 9,357 Weather: 73°, SW at 21 mph Hirokazu Sawamura 26 (16) Braves HR: None Garrett Whitlock 36 (28) Red Sox HR: None BRAVES Pitcher # (Strikes) Charlie Morton 103 (71) RED SOX NOTES (29-20) Edgar Santana 18 (9) Will Smith 14 (9) THE RED SOX have lost each of their last 2 games following a 4-game winning streak...Are 7-4 in their last 11 games. Scored 1 or 0 runs for the 8th time (previous: 5/18 at TOR, 0)...Had 3 or fewer hits for the 3rd time (previous: 4/29 at TEX, 3). GARRETT RICHARDS (5.2 IP, 6 H, 3 R, 4 BB, 4 SO) held the Braves to 2 runs through 5.0 innings before being charged with an ER in the 6th. -

Signature Redacted

STAMP Applied to Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster and the Safety of Nuclear Power Plants in Japan by Daisuke Uesako M.E., Environmental & Ocean Engineering, University of Tokyo, 2007 B.E.., Systems Innovation, University of Tokyo, 2005 Submitted to the System Design and Management Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Engineering and Management MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOWGY at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology OCT 26 2016 June 2016 LIBRARIES 2016 Daisuke Uesako. All rights reserved. ARCHIVES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: Signature redacted Daisuke Uesako System Design and Management Program May 6, 2016 Certified by: _ Signature redacted Nancy Leveson r , Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: _ oignalure redacted Patrick Hale Director System Design and Management Program STAMP applied to Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster and the safety of nuclear power plants in Japan by Daisuke Uesako Submitted to the System Design and Management Program on May 6, 2016 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering and Management' ABSTRACT On March 11, 2011, a huge tsunami generated after the Great East Japan Earthquake triggered an extremely severe nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. This thesis analyzes why the stakeholders could not prevent the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, and, with regard to the future nuclear safety in Japan, what the potentially hazardous control actions could be. -

Download PDF (658K)

Journal of Epidemiology Letter to the Editor J Epidemiol 2021;31(7):453-455 Coronavirus Disease and the Shared Emotion of Blaming Others: Reviewing Media Opinion Polls During the Pandemic Yusuke Inoue1 and Taketoshi Okita2 1Department of Public Policy, The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan 2Department of Medical Ethics, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, Sendai, Japan Received March 19, 2021; accepted April 14, 2021; released online April 24, 2021 Copyright © 2021 Yusuke Inoue et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. In Japan, the revised Infectious Diseases Control Law1 and Yomiuri-NNN: April (a) and June (c) 2020, January (g, m) 2021; other amending acts, passed in February 2021, newly stipulates TBS-JNN: May (b) 2020, January (f ) 2021; Asahi: November administrative penalties for those who refuse hospitalization and (d, e) 2020, January (l, q) 2021; NHK: January (i) 2021; Kyodo: testing and those who do not comply with shortened business January (h) 2021; Mainichi-SSRC: January (n) 2021; ANN: hours when required. Considering that Japan’s countermeasures January ( j, o) 2021; and Fuji-Sankei: January (k, p) 2021. The against infectious diseases rely on individual voluntary behavioral average number of respondents in each survey was 1,441 changes, this revision of the law may become one of the major (minimum: 520; maximum: 2,187). The survey periods were turning points for such countermeasures. Introducing penalties as largely divided into April to June 2020 (first phase), November a response to a pandemic should be considered with great caution. -

< Sister and Friendship Cities/States >

< Sister and Friendship Cities/States > City/State Basic Information New York City Country: United States of America Date of agreement: February 29, 1960 Area: 784 ㎢ Signed by: Population: 8.40 million Robert F. Wagner, Jr., Mayor of New York City Ryotaro Azuma, Governor of Tokyo Current mayor: Bill de Blasio (January 2014 –present) New York City website https://www1.nyc.gov/ Beijing Municipal Government Country: People’s Republic of China Date of agreement: March 14, 1979 Area: 16,410 ㎢ Signed by: Population: 21.71 million Lin Hujia, Mayor of Beijing Ryokichi Minobe, Governor of Tokyo Current mayor: Chen Jining (January 2018– present) City of Beijing English website http://www.ebeijing.gov.cn/ City of Paris Country: French Republic Date of agreement: July 14, 1982 Area: 105 ㎢ Signed by: Population: 2.30 million Jacques Chirac, Mayor of Paris Shunichi Suzuki, Governor of Tokyo Current mayor: Anne Hidalgo (April 2014 – present) City of Paris website https://www.paris.fr/ Paris Convention and Visitors Bureau English website http://en.parisinfo.com/ ★ City/State Basic Information State of New South Wales Country: Australia Date of agreement: May 9, 1984 Area: 809,400 ㎢ Population: 7.95 million Signed by: Neville. K. Wran, Premier of New South Wales Current premier: Gladys Berejiklian (January 2017 – present) Shunichi Suzuki, Governor of Tokyo New South Wales website https://www.nsw.gov.au/ Official tourism site for New South Wales https://www.sydney.com/ Seoul Metropolitan Government Country: Republic of Korea Date of agreement: September -

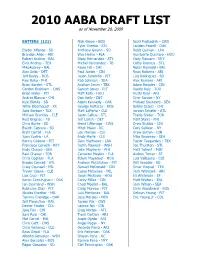

2010 AABA DRAFT LIST As of November 20, 2009

2010 AABA DRAFT LIST as of November 20, 2009 BATTERS (131) Nick Green - BOS Scott Podsednik - CWS Tyler Greene - STL Landon Powell - OAK Eliezer Alfonzo - SD Anthony Gwynn - SD Robb Quinlan - LAA Brandon Allen - ARI Wes Helms - FLA Humberto Quintero - HOU Robert Andino - BAL Diory Hernandez - ATL Cody Ransom - NYY Elvis Andrus - TEX Michel Hernandez - TB Colby Rasmus - STL MikeAubrey - BAL Koyie Hill - CHI Nolan Reimold - BAL Alex Avila - DET Paul Janish - CIN Ryan Roberts - ARI Jeff Bailey - BOS Jason Jaramillo - PIT Luis Rodriguez - SD Paul Bako - PHI Rob Johnson - SEA Alex Romero - ARI Brian Barden - STL Andruw Jones - TEX Adam Rosales - CIN Gordon Beckham - CWS Garrett Jones - PIT Randy Ruiz - TOR Brian Bixler - PIT Matt Kata - HOU Rusty Ryal - ARI Andres Blanco - CHI Don Kelly - DET Omir Santos - NY Kyle Blanks - SD Adam Kennedy - OAK Michael Saunders - SEA Willie Bloomquist - KC George Kottaras - BOS Bobby Scales - CHI Julio Borbon - TEX Matt LaPorta - CLE Jordan Schafer - ATL Michael Brantley - CLE Jason LaRue - STL Travis Snider - TOR Reid Brignac - TB Jeff Larish - DET Matt Stairs - PHI Chris Burke - SD Brent Lillibridge - CWS Drew Stubbs - CIN Everth Cabrera - SD Mitch Maier - KC Cory Sullivan - NY Brett Carroll - FLA Lou Marson - CLE Drew Sutton - CIN Juan Castro - LA Andy Marte - CLE Mike Sweeney - SEA Ronny Cedeno - PIT Gary Matthews - LAA Taylor Teagarden - TEX Francisco Cervelli - NYY Justin Maxwell - WSH Joe Thurston - STL Endy Chavez - SEA John Mayberry - PHI Matt Tolbert - MIN Raul Chavez - TOR Cameron Maybin - FLA Andres -

Other Useful Statements and Database Joins

Other Useful Statements and Database Joins SWEN-250: Personal Software Engineering Overview • Other Useful Statements: • Database Info: • SELECT Functions • .tables • SELECT Like • .schema • ORDER BY • LIMIT • Joins: • UPDATE • LEFT JOIN • DELETE • RIGHT JOIN • ALTER TABLE • INNER JOIN • DROP TABLE • FULL OUTER JOIN SWEN-250 Personal Software Engineering Other Useful Statements SWEN-250 Personal Software Engineering SELECT Functions SELECT AVG(grade) FROM students; SELECT SUM(grade) FROM students; SELECT MIN(grade) FROM students; SELECT MAX(grade) FROM students; SELECT count(id) FROM students; There are various functions that you can apply to the values returned from a select statement (many more on the reference pages). sqlite> select COUNT(*) FROM Player; COUNT(*) 125 sqlite> select SUM(age) FROM Player; SUM(age) 3560 sqlite> select AVG(age) FROM Player; AVG(age) 28.48 sqlite> select MIN(age) FROM Player; MIN(age) 20 sqlite> select MAX(AGE) FROM Player; SWEN-250 Personal Software Engineering SELECT Like SELECT * FROM Player WHERE name LIKE "K%"; You can use like to do partial string matching. The '%;' character acts like a wild card. The above will select all players whose name begins with K. sqlite> SELECT * FROM Player WHERE name LIKE "K%"; name|position|number|team|age Koji Uehara|1|19|Red Sox|40 Kevin Gausman|1|39|Orioles|24 Kevin Pillar|7|11|Blue Jays|26 Kevin Jepsen|1|40|Rays|30 SWEN-250 Personal Software Engineering ORDER BY SELECT * FROM Player ORDER BY name; Putting 'ORDER BY' at the end of a select statement will sort the output by the column name. There is also a 'REVERSE ORDER BY' which does the opposite sorted order (note that it looks like this is not working in sqlite3). -

Baseball in Japan and the US History, Culture, and Future Prospects by Daniel A

Sports, Culture, and Asia Baseball in Japan and the US History, Culture, and Future Prospects By Daniel A. Métraux A 1927 photo of Kenichi Zenimura, the father of Japanese-American baseball, standing between Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth. Source: Japanese BallPlayers.com at http://tinyurl.com/zzydv3v. he essay that follows, with a primary focus on professional baseball, is intended as an in- troductory comparative overview of a game long played in the US and Japan. I hope it will provide readers with some context to learn more about a complex, evolving, and, most of all, Tfascinating topic, especially for lovers of baseball on both sides of the Pacific. Baseball, although seriously challenged by the popularity of other sports, has traditionally been considered America’s pastime and was for a long time the nation’s most popular sport. The game is an original American sport, but has sunk deep roots into other regions, including Latin America and East Asia. Baseball was introduced to Japan in the late nineteenth century and became the national sport there during the early post-World War II period. The game as it is played and organized in both countries, however, is considerably different. The basic rules are mostly the same, but cultural differences between Americans and Japanese are clearly reflected in how both nations approach their versions of baseball. Although players from both countries have flourished in both American and Japanese leagues, at times the cultural differences are substantial, and some attempts to bridge the gaps have ended in failure. Still, while doubtful the Japanese version has changed the American game, there is some evidence that the American version has exerted some changes in the Japanese game. -

Barbed Wire Baseball to Students and Start a Discussion on the Following Topics: 1

Curriculum Guide Introduce students to Japanese-American internment during WWII using book as a springboard for discussions. The subject fits into learning national learning standards for U.S. History. Standard topics: • Living and Working Together in Families Now and Long Ago • The History of the United States: Democratic Principles and Values and the People form Many • Cultures who Contributed to is Cultural, Economic, and Political Heritage. • The Great Depression and World War II: the implication of the Japanese-American internment for civil liberties. Objective: • To introduce history of Japanese-American internment, its causes and effects. • To understand how difficult conditions can inspire creativity and resourcefulness. • To understand how hardship can both bond and/or weaken communities, how it can strengthen and/or destroy individuals. • To gain a different perspective to a historical event. Key Terms/Concepts: • Civil Rights • Internment • Resiliency • Prejudice • Patriotism Background Information When Pearl Harbor was bombed in 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the internment of all people of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast. More than 110,000 people were forced to leave their homes, two-thirds of them U.S. Citizens. They lost their property, their businesses, their communities. Although they were loyal Americans, they were considered dangerous anyway, possible spies for Japan. Kenichi Zenimura and his family were sent to Gila River, Arizona. Zeni may have started his baseball career on a Japanese-only team in Fresno because the regular white teams wouldn’t allow him to play, but he ended up playing with Yankee greats like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig for exhibition games. -

Today's Game Information

Sunday, April 28, 2013 Game #27 (10-16) Safeco Field LOS ANGELES ANGELS (9-14) vs. SEATTLE MARINERS (10-16) Home #14 (6-7) TODAY’S GAME INFORMATION Starting Pitchers: LHP Jason Vargas (0-2, 5.82) vs. RHP Hisashi Iwakuma (2-1, 1.99) 1:10 p.m. • Radio: 710 ESPN Seattle / Mariners.com • TV: ROOT Sports Day Date Opp. Time Mariners Pitcher Opposing Pitcher TELEVISION Monday April 29 BAL 7:10 pm LH Joe Saunders (1-3, 6.33) vs. LH Zach Britton (1st 2013 app.) ROOT Sports Tuesday April 30 BAL 7:10 pm RH Brandon Maurer (2-3, 5.61) vs. RH Jason Hammel (3-1, 3.82) ROOT Sports Wednesday May 1 BAL 7:10 pm RH Aaron Harang (0-3, 11.37) vs. LH Wei-Yin Chen (2-2, 2.53) ROOT Sports Thursday May 2 Travel Day to Toronto All games broadcast on 710 ESPN Seattle & Mariners Radio Network & in home games in Spanish on ESPN Deportes Local Radio Group Spanish Audio available for 79 of 81 home games, presented by ROOT SPORTS via SAP (where available) TODAY’S TILT…the Mariners continue a 2-team, 7-game homestand against the Los Angeles HOMESTAND HIGHLIGHTS Angels (2-1, 1 game remaining) and Baltimore Orioles (3G) tonight…today’s game will be televised A number of exciting events highlight on ROOT Sports in high definition & broadcast live on 710 ESPN Seattle & Mariners Radio Network. the Mariners second homestand of the season, a 7-gamer vs. the Angels ODDS AND ENDS…are 8-16 after opening the season 2-0; have not won consecutive games since the (4 G) and Orioles (3 G) at Safeco Field, including the following upcoming first two games of the season…12 of the Mariners first 26 games have been decided by 2-or-fewer runs promotions: (6-6), and featured 3 extra inning affairs (1-2).