The Return of Sir Ernest Shackleton Author(S): Hugh Robert Mill Source: the Geographical Journal, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report Concerning the Preparation of the Third Edition of the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans

REPORT CONCERNING THE PREPARATION OF THE THIRD EDITION OF THE GENERAL BATHYMETRIC CHART OF THE OCEANS by Captain H .L.G . BENCKER, Secretary-General of the International Hydrographic Bureau. (Brought up to date as of 31st December, 1952). In the month of June 1930, the International Hydographic Bureau drew up a report concerning the Bathymetric Soundings of the Oceans; this was presented at the Fourth General Assembly of the International Geodetic and Geophysical Union (Section of Physical Oceanography) at Stockholm in August 1930. It is not our intention to repeat here the details and arguments contained in the monograph referred to, which was reproduced in the Hydrographic Review, Volume V II, No. 2, Monaco, November 1930, pages 64-97, to which the reader may refer should he deem it necessary. Below, however, is given a brief outline o'f the efforts which have been made up to the present to keep up the elementary record of our knowledge concerning the topography of the ocean-bottom, grouped in its most general sense. The following is a chronological list of the fundamental compilations made on this subject since the middle of last century, with the names of their authors: 1854. M. F. M aury, U.S.N. — Map of the Basin of the North Atlantic, Cf. The Physical Geography of the Sea (1860). 1874. J. P rESTWICH. — Planisphere of the Oceans (Phil. Trans. Royal Society, London, 1874, p. 674). 1886. Sir John Murray. — Physical Charts of the World, Charts IA, IB, 1C, annexed to the Report of the Challenger Expedition (1872-1876) : Summary of Scientific Results, London, 1875. -

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

A NEWS BULLETIN Published Quarterly by the NEW ZEALAND

A N E W S B U L L E T I N p u b l i s h e d q u a r t e r l y b y t h e NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY THESE VISITORS TO LAKE FRYXELL IN THE TAYLOR VALLEY ARE LIKE DWARFS AGAINST THE TOWERING CANADA GLACIER WHICH FLOWS DOWN FROM THE ASGAARD RANGE. —Photo by R. K. McBride. Antarctic Division, D.S.I.R. September 1972 «i (Successor to "Antarctic News Bulletin") Vol. 6, No. 7 67th ISSUE Editor: H. F. GRIFFITHS, 14 Woodchester Avenue, Christchurch 1. Assistant Editor: J. M. CAFFIN, 35 Chepstow Avenue, Christchurch 5. Address all contributions, enquiries, etc., to the Editor. All Business Communications, Subscriptions, etc., to: The Secretary, New Zealand Antarctic Society, P.O. Box 1223, Christchurch, N.Z CONTENTS ARTICLES SECOND-IN-COMMAND POLAR ACTIVITIES NEW ZEALAND 222, 225, 231, 240, 243, 251, 253 U.S.A 226, 232, 252 AUSTRALIA 236 UNITED KINGDOM 234 U.S.S.R 238, 239, 241 SOUTH AFRICA 242, 250 CZECHOSLOVAKIA 235 SUB-ANTARCTIC CAMPBELL ISLAND GENERAL LONE TRIP TO POLE DISCOVERY EXPEDITION LETTERS WHALING QUOTAS FIXED ANTARCTIC BOOKSHELF Fifteen years have passed since the International Geophysical Year of 1957-58 and it might be thought that the Antarctic Continent, through the continuing research carried out by the participating nations, would by now have yielded up all its secrets. But this is a false premise; new discoveries in the various branches of science have either highlighted gaps in our knowledge or have pointed the way to investigation in new fields. -

Thesis Template

Thinking with photographs at the margins of Antarctic exploration A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Canterbury by Kerry McCarthy University of Canterbury 2010 Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... 2 List of Figures and Tables ............................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................... 6 Abstract ........................................................................................................................... 7 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Thinking with photographs ....................................................................... 10 1.2 The margins ............................................................................................... 14 1.3 Antarctic exploration ................................................................................. 16 1.4 The researcher ........................................................................................... 20 1.5 Overview ................................................................................................... 22 2 An unauthorised genealogy of thinking with photographs .............................. 27 2.1 The -

JOURNAL Number Six

THE JAMES CAIRD SOCIETY JOURNAL Number Six Antarctic Exploration Sir Ernest Shackleton MARCH 2012 1 Shackleton and a friend (Oliver Locker Lampson) in Cromer, c.1910. Image courtesy of Cromer Museum. 2 The James Caird Society Journal – Number Six March 2012 The Centennial season has arrived. Having celebrated Shackleton’s British Antarctic (Nimrod) Expedition, courtesy of the ‘Matrix Shackleton Centenary Expedition’, in 2008/9, we now turn our attention to the events of 1910/12. This was a period when 3 very extraordinary and ambitious men (Amundsen, Scott and Mawson) headed south, to a mixture of acclaim and tragedy. A little later (in 2014) we will be celebrating Sir Ernest’s ‘crowning glory’ –the Centenary of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic (Endurance) Expedition 1914/17. Shackleton failed in his main objective (to be the first to cross from one side of Antarctica to the other). He even failed to commence his land journey from the Weddell Sea coast to Ross Island. However, the rescue of his entire team from the ice and extreme cold (made possible by the remarkable voyage of the James Caird and the first crossing of South Georgia’s interior) was a remarkable feat and is the reason why most of us revere our polar hero and choose to be members of this Society. For all the alleged shenanigans between Scott and Shackleton, it would be a travesty if ‘Number Six’ failed to honour Captain Scott’s remarkable achievements - in particular, the important geographical and scientific work carried out on the Discovery and Terra Nova expeditions (1901-3 and 1910-12 respectively). -

The Reception and Commemoration of William Speirs Bruce Are, I Suggest, Part

The University of Edinburgh School of Geosciences Institute of Geography A SCOT OF THE ANTARCTIC: THE RECEPTION AND COMMEMORATION OF WILLIAM SPEIRS BRUCE M.Sc. by Research in Geography Innes M. Keighren 12 September 2003 Declaration of originality I hereby declare that this dissertation has been composed by me and is based on my own work. 12 September 2003 ii Abstract 2002–2004 marks the centenary of the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition. Led by the Scots naturalist and oceanographer William Speirs Bruce (1867–1921), the Expedition, a two-year exploration of the Weddell Sea, was an exercise in scientific accumulation, rather than territorial acquisition. Distinct in its focus from that of other expeditions undertaken during the ‘Heroic Age’ of polar exploration, the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition, and Bruce in particular, were subject to a distinct press interpretation. From an examination of contemporary newspaper reports, this thesis traces the popular reception of Bruce—revealing how geographies of reporting and of reading engendered locally particular understandings of him. Inspired, too, by recent work in the history of science outlining the constitutive significance of place, this study considers the influence of certain important spaces—venues of collection, analysis, and display—on the conception, communication, and reception of Bruce’s polar knowledge. Finally, from the perspective afforded by the centenary of his Scottish National Antarctic Expedition, this paper illustrates how space and place have conspired, also, to direct Bruce’s ‘commemorative trajectory’—to define the ways in which, and by whom, Bruce has been remembered since his death. iii Acknowledgements For their advice, assistance, and encouragement during the research and writing of this thesis I should like to thank Michael Bolik (University of Dundee); Margaret Deacon (Southampton Oceanography Centre); Graham Durant (Hunterian Museum); Narve Fulsås (University of Tromsø); Stanley K. -

Ernest Shackleton and the Epic Voyage of the Endurance

9-803-127 REV: DECEMBER 2, 2010 NANCY F. KOEHN Leadership in Crisis: Ernest Shackleton and the Epic Voyage of the Endurance For scientific discovery give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel give me Amundsen; but when disaster strikes and all hope is gone, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton. — Sir Raymond Priestley, Antarctic Explorer and Geologist On January 18, 1915, the ship Endurance, carrying a highly celebrated British polar expedition, froze into the icy waters off the coast of Antarctica. The leader of the expedition, Sir Ernest Shackleton, had planned to sail his boat to the coast through the Weddell Sea, which bounded Antarctica to the north, and then march a crew of six men, supported by dogs and sledges, to the Ross Sea on the opposite side of the continent (see Exhibit 1).1 Deep in the southern hemisphere, it was early in the summer, and the Endurance was within sight of land, so Shackleton still had reason to anticipate reaching shore. The ice, however, was unusually thick for the ship’s latitude, and an unexpected southern wind froze it solid around the ship. Within hours the Endurance was completely beset, a wooden island in a sea of ice. More than eight months later, the ice still held the vessel. Instead of melting and allowing the crew to proceed on its mission, the ice, moving with ocean currents, had carried the boat over 670 miles north.2 As it moved, the ice slowly began to soften, and the tremendous force of distant currents alternately broke apart the floes—wide plateaus made of thousands of tons of ice—and pressed them back together, creating rift lines with huge piles of broken ice slabs. -

1 Compiled by Mike Wing New Zealand Antarctic Society (Inc

ANTARCTIC 1 Compiled by Mike Wing US bulldozer, 1: 202, 340, 12: 54, New Zealand Antarctic Society (Inc) ACECRC, see Antarctic Climate & Ecosystems Cooperation Research Centre Volume 1-26: June 2009 Acevedo, Capitan. A.O. 4: 36, Ackerman, Piers, 21: 16, Vessel names are shown viz: “Aconcagua” Ackroyd, Lieut. F: 1: 307, All book reviews are shown under ‘Book Reviews’ Ackroyd-Kelly, J. W., 10: 279, All Universities are shown under ‘Universities’ “Aconcagua”, 1: 261 Aircraft types appear under Aircraft. Acta Palaeontolegica Polonica, 25: 64, Obituaries & Tributes are shown under 'Obituaries', ACZP, see Antarctic Convergence Zone Project see also individual names. Adam, Dieter, 13: 6, 287, Adam, Dr James, 1: 227, 241, 280, Vol 20 page numbers 27-36 are shared by both Adams, Chris, 11: 198, 274, 12: 331, 396, double issues 1&2 and 3&4. Those in double issue Adams, Dieter, 12: 294, 3&4 are marked accordingly. Adams, Ian, 1: 71, 99, 167, 229, 263, 330, 2: 23, Adams, J.B., 26: 22, Adams, Lt. R.D., 2: 127, 159, 208, Adams, Sir Jameson Obituary, 3: 76, A Adams Cape, 1: 248, Adams Glacier, 2: 425, Adams Island, 4: 201, 302, “101 In Sung”, f/v, 21: 36, Adamson, R.G. 3: 474-45, 4: 6, 62, 116, 166, 224, ‘A’ Hut restorations, 12: 175, 220, 25: 16, 277, Aaron, Edwin, 11: 55, Adare, Cape - see Hallett Station Abbiss, Jane, 20: 8, Addison, Vicki, 24: 33, Aboa Station, (Finland) 12: 227, 13: 114, Adelaide Island (Base T), see Bases F.I.D.S. Abbott, Dr N.D. -

The Life of Sir Ernest Shackleton CVO

CO of % The Estate of the late John Brand le 7/ THE LIFE OF Sir ERNEST SHACKLETON BOOKS BY SIR ERNEST SHACKLETON THE HEART OF THE ANTARCTIC. Being the Story of the British Antarctic Expedition, 1907-1909. SOUTH. The Story of Shackleton's Last Expedition, 1914-1917. LONDON : WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD. \ Phoio.\ \Speaight Ltd. Sir Ernest Shackleton, aged 40, with his Younger Son, aged 3. Frontispiece. ^ THE LIFE OF BiR ERNEST SHACKLETON C.V.O., O.B.E.(M/.), LL.D. BY HUGH ROBERT MILL Do your best, whether winning or losing it, If you choose to play ! —is my principle. Let a man contend to the uttermost For his life's set prize, be it what it will ! Robert Browning LONDON : WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD. MCMXXIII f ^ . 1964 275^ ) ^5Mr 944918 MAPE ANU PRINTED IN UREAT BRITAIN TO THOSE WHO KNEW HIM BEST BECAUSE THEY LOVED HIM MOST PREFACE a life of a man of action may fitly be presented as THEcontinuous narrative of his doings, from which a reader may gain a clear sense of the personality and trace the growth of character. Shackleton's life as it ran on seems in retrospect to have passed through three periods now presented in three books : of the the first, Equipment for the Achievement the second ; third. Bafflement, which an unconquerable optimism saved from defeat. Each of the three periods includes a series of distinct but consequent experiences forming natural chapters. Such an arrangement leaves little room for generahties, and requires an Epilogue in which the essence of the life may be sublimed from the facts. -

Final Report of the Twenty-Ninth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting

Final Report of the Twenty-ninth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting ANTARCTIC TREATY CONSULTATIVE MEETING Final Report of the Twenty-ninth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting Edinburgh, United Kingdom 12 – 23 June 2006 Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty Buenos Aires 2006 Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (29th : 2006 : Edinburgh) Final Report of the Twenty-ninth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting. Edinburgh, United Kingdom, 12-23 June 2006. Buenos Aires : Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty, 2006. 564 p. ISBN 987-23163-0-9 1. International law – Environmental issues. 2. Antarctic Treaty System. 3. Environmental law – Antarctica. 4. Environmental protection – Antarctica. DDC 341.762 5 ISBN-10: 987-23163-0-9 ISBN-13: 978-987-23163-0-3 CONTENTS Acronyms and Abbreviations 9 I. FINAL REPORT 11 II. MEASURES, DECISIONS AND RESOLUTIONS 49 A. Measures 51 Measure 1 (2006): Antarctic Specially Protected Areas: Designations and Management Plans 53 Annex A: ASPA No. 116 - New College Valley, Caughley Beach, Cape Bird, Ross Island 57 Annex B: ASPA No. 127 - Haswell Island (Haswell Island and Adjacent Emperor Penguin Rookery on Fast Ice) 69 Annex C: ASPA No. 131 - Canada Glacier, Lake Fryxell, Taylor Valley, Victoria Land 83 Annex D: ASPA No. 134 - Cierva Point and offshore islands, Danco Coast, Antarctic Peninsula 95 Annex E: ASPA No. 136 - Clark Peninsula, Budd Coast, Wilkes Land 105 Annex F: ASPA No. 165 - Edmonson Point, Wood Bay, Ross Sea 119 Annex G: ASPA No. 166 - Port-Martin, Terre Adélie 143 Annex H: ASPA No. 167 - Hawker Island, Vestfold Hills, Ingrid Christensen Coast, Princess Elizabeth Land, East Antarctica 153 Measure 2 (2006): Antarctic Specially Managed Area: Designation and Management Plan: Admiralty Bay, King George Island 167 Annex: Management Plan for ASMA No. -

The Enduring Books of Shackleton's Endurance

The Enduring Books of Shackleton’s Endurance: A Polar Reading Community at Sea David H. Stam Introduction After twenty years of Antarctic centenary anniversaries celebrating the “heroic age” of polar exploration, and its eponymous “heroes” Fridtjof Nansen, Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, Douglas Mawson, Ernest Shackleton, and others, it hardly seems necessary to recount yet again the story of Ernest Shackleton’s “epic voyage” of Endurance and his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-16 (ITAE). Its praises have been sung and its faults analyzed constantly during this period by hagiographers and debunkers and just about everyone in between. Materials have appeared in print, in movies, documentaries, exhibitions, in poetry and song, in comics and ceramics, among management gurus, in art, on cigarette cards, even in philately. The source of much of this attention, in North America at least, was a 1999 exhibition simply called “Shackleton” at New York’s American Museum of Natural History, and a large literature immediately followed.1 In this study, I have tried to draw together all of the known documentary evidence about the book history and reading experiences of the journey. In effect, I am retelling the story of Endurance from the perspective of a reading community. The framework for the narrative begins with the role of Shackleton himself as the community leader, as a consummate bookman, an early and voracious reader, and an eager consumer of poetry who claimed to prefer history to fiction. Roland Huntford sums up Shackleton’s early literary appetite thus: Shackleton, at any rate, was proving to be at home with all kinds of men, but he was still “old Shacks” always “busy with his books”. -

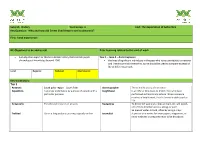

Subject: History Year Group: 6 Unit: the Exploration of Antarctica Key Question: Why and How Did Ernest Shackleton Travel to Antarctic?

Subject: History Year Group: 6 Unit: The Exploration of Antarctica Key Question: Why and how did Ernest Shackleton travel to Antarctic? First- hand experience: NC Objectives to be addressed: Prior Learning related to this unit of work • A study of an aspect or theme in British history that extends pupils’ Year 1 – term 2 – Arctic Explorers chronological knowledge beyond 1066 • the lives of significant individuals in the past who have contributed to national and international achievements, some should be used to compare aspects of life in different periods Local Regional National International Key Vocabulary: Tier 3 Antarctic South polar region – South Pole Oceanographer The scientific study of the ocean Expedition A journey undertaken by a group of people with a Knighthood Is an official title given to British men who have particular purpose performed extraordinary service. When someone receives a knighthood, they're formally addressed as "Sir. Geographic The physical features of an area. Navigating To direct the way that a ship, aircraft, etc. will travel, or to find a direction across, along, or over an area of water or land, often by using a map: Trekked Go on a long arduous journey, typically on foo Journalist A person who writes for newspapers, magazines, or news websites or prepares news to be broadcast Sequence of learning: Knowledge to be taught (Declarative): Note – please teach in conjunction with the Geography plan for this unit of work. 1 • Ernest Henry Shackleton was born in Ireland on February 15th 1874. His father, Henry Shackleton was a landowner at the time. His mother was called Henrietta.