After Artest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mississippi State 2020-21 Basketball

11 NCAA TOURNAMENT APPEARANCES 1963 • 1991 • 1995 • 1996 • 2002 • 2003 MISSISSIPPI STATE 2004 • 2005 • 2008 • 2009 • 2019 MEN’S BASKETBALL CONTACT 2020-21 BASKETBALL MATT DUNAWAY • [email protected] OFFICE (662) 325-3595 • CELL (727) 215-3857 Mississippi State (14-12 • 8-9 SEC) vs. Auburn (12-14 • 6-11 SEC) GAME 27 • AUBURN ARENA • AUBURN, ALABAMA • SATURDAY, MARCH 6 • 12:00 P.M. CT 27 TV: SEC NETWORK • WATCH ESPN APP • RADIO: 100.9 WKBB-FM • STARKVILLE • ONLINE: HAILSTATE.COM • TUNE-IN RADIO APP MISSISSIPPI STATE (14-12 • 8-9 SEC) MISSISSIPPI STATE POSSIBLE STARTING LINEUP • BASED ON PREVIOUS GAMES H: 9-6 • A: 5-3 • N: 0-3 • OT: 0-2 NO. 1 IVERSON MOLINAR • G • 6-3 • 190 • SO. • PANAMA CITY, PANAMA NOVEMBER • 1-2 2020-21 • 16.3 PPG • 140-297 FG • 32-71 3-PT FG • 64-80 FT • 3.9 RPG • 2.6 APG • 1.1 SPG Space Coast Challenge • Melbourne, Florida • Nov. 25-26 Wed. 25 vs. Clemson • CBS-SN L • 53-42 LAST GAME • AT TEXAS A&M • 18 PTS • 7-12 FG • 2-5 3-PT FG • 2-4 FT • 5 REB • 3 ASST • 1 STL Thur. 26 vs. Liberty • CBS-SN L • 84-73 • Molinar is an explosive combo guard who is a talented shooter, passer and slasher that can get to the rim • 16.3 PPG is 6th in the SEC (03/06) Mon. 30 Texas State • SECN W • 68-51 • Dialed up career-high 24 PTS at UGA (12/30) and at VANDY (01/09) • Howland: Molinar’s jump from FR/SOPH reminds him of Russell Westbrook at UCLA DECEMBER • 5-1 • 10+ PTS in 20 of his 23 outings and 6 GMS of 20+ PTS in 2020-21 • His +10.4 PPG is T-8th largest FR/SOPH scoring jump in SEC over last decade Fri. -

ROCKETS 2014-15 National Treasures Basketball Team CHECKLIST

2014-15 National Treasures Basketball Team CHECKLIST ROCKETS Player Card Set Card # Team Print Run Cedric Maxwell Career Materials Trios + Prime Parallel 3 Rockets 40 Clyde Drexler Clutch Factor Auto Relic + Prime Parallel 7 Rockets 35 Clyde Drexler Colossal Jerseys Signatures + Prime Parallel 9 Rockets 35 Clyde Drexler Lasting Legacies Auto Relic + Prime Parallel 16 Rockets 35 Clyde Drexler NBA Champions Signatures 1 Rockets 49 Clyde Drexler NBA Game Gear Signatures + Prime 6 Rockets 35 Clyde Drexler Scripts Auto + Parallels 19 Rockets 60 Dikembe Mutombo Career Materials Trios + Prime Parallel 5 Rockets 65 Dikembe Mutombo Career Materials Trios Prime Laundry Tags 5 Rockets 2 Dikembe Mutombo Springfield Swatches + Prime Parallel 20 Rockets 60 Donatas Motiejunas Air Apparent Laundry Tags 24 Rockets 5 Donatas Motiejunas Air Apparent Relic + Prime Parallel 24 Rockets 74 Donatas Motiejunas Material Treasures Signatures + Prime Parallel 5 Rockets 74 Donatas Motiejunas Material Treasures Signatures Laundry Tag 5 Rockets 5 Dwight Howard Base + Parallels 44 Rockets 140 Dwight Howard Career Materials Trios + Prime Parallel 7 Rockets 104 Dwight Howard Career Materials Trios Prime Laundry Tags 7 Rockets 3 Dwight Howard Material Treasures Signatures + Prime Parallel 54 Rockets 35 Dwight Howard Material Treasures Signatures Laundry Tag 54 Rockets 5 Dwight Howard NBA Game Gear Dual Relic + Prime Parallel 42 Rockets 124 Dwight Howard NBA Game Gear Duals Prime Laundry Tags 42 Rockets 2 Dwight Howard NBA Material + Prime Parallel 32 Rockets 124 Dwight -

BCS Commissioners Agree on Four-Team Playoff

B2 THURSDAY, JUNE 21, 2012 SCOREBOARD LEXINGTON HERALD-LEADER | KENTUCKY.COM COLLEGE FOOTBALL Transactions THURSDAY’S LINEUP BASEBALL Focus on: Auto racing this week American League BCS commissioners BOSTON RED SOX — Agreed to NASCAR terms with SS Deven Marrero on a mi- TOYOTA/SAVE MART 350 nor league contract and assigned him Where: Sonoma, Calif. agree on four-team playoff to Lowell (NYP). When: Friday, practice (Speed, 3-4:30 p.m.), qualify- CLEVELAND INDIANS — Assigned ing (Speed, 11 p.m.-1 a.m.); Saturday, practice (Speed, 11 The BCS commissioners reached a consensus Wednesday on a RHP Joshua Nervis, RHP Dylan Baker, TV, radio p.m.-12:30 a.m.); Sunday, race, 3 p.m. (TNT, 2-6:30 p.m.) model for a four-team, seeded playoff that will be presented to the OF Josh McAdams, OF Tyler Booth and RHP Kieran Lovegrove to the Arizona Track: Infineon Raceway (road course, 1.99 miles) BASEBALL university presidents next week for approval. All that’s left is for the League Indians. Distance: 218.9 miles, 110 laps Noon College World Series: Kent State vs. South Carolina ESPN2 presidents to sign off and major college football’s champion will be KANSAS CITY ROYALS — Optioned Last year: Kurt Busch raced to his first career road- 4 p.m. College World Series: Arizona vs. Florida State ESPN2 decided by playoff come the 2014 season. RHP Louis Coleman to Omaha (PCL). course victory, leading 76 laps. Jeff Gordon was second. Recalled 2B Irving Falu from Omaha. 7 p.m. MLB: Marlins at Red Sox or Rockies at Phillies MLB The commissioners have been working on reshaping college LOS ANGELES ANGELS — Assigned Fast facts: Daytona 500 winner Matt Kenseth leads 7:05 p.m. -

Rosters Set for 2014-15 Nba Regular Season

ROSTERS SET FOR 2014-15 NBA REGULAR SEASON NEW YORK, Oct. 27, 2014 – Following are the opening day rosters for Kia NBA Tip-Off ‘14. The season begins Tuesday with three games: ATLANTA BOSTON BROOKLYN CHARLOTTE CHICAGO Pero Antic Brandon Bass Alan Anderson Bismack Biyombo Cameron Bairstow Kent Bazemore Avery Bradley Bojan Bogdanovic PJ Hairston Aaron Brooks DeMarre Carroll Jeff Green Kevin Garnett Gerald Henderson Mike Dunleavy Al Horford Kelly Olynyk Jorge Gutierrez Al Jefferson Pau Gasol John Jenkins Phil Pressey Jarrett Jack Michael Kidd-Gilchrist Taj Gibson Shelvin Mack Rajon Rondo Joe Johnson Jason Maxiell Kirk Hinrich Paul Millsap Marcus Smart Jerome Jordan Gary Neal Doug McDermott Mike Muscala Jared Sullinger Sergey Karasev Jannero Pargo Nikola Mirotic Adreian Payne Marcus Thornton Andrei Kirilenko Brian Roberts Nazr Mohammed Dennis Schroder Evan Turner Brook Lopez Lance Stephenson E'Twaun Moore Mike Scott Gerald Wallace Mason Plumlee Kemba Walker Joakim Noah Thabo Sefolosha James Young Mirza Teletovic Marvin Williams Derrick Rose Jeff Teague Tyler Zeller Deron Williams Cody Zeller Tony Snell INACTIVE LIST Elton Brand Vitor Faverani Markel Brown Jeffery Taylor Jimmy Butler Kyle Korver Dwight Powell Cory Jefferson Noah Vonleh CLEVELAND DALLAS DENVER DETROIT GOLDEN STATE Matthew Dellavedova Al-Farouq Aminu Arron Afflalo Joel Anthony Leandro Barbosa Joe Harris Tyson Chandler Darrell Arthur D.J. Augustin Harrison Barnes Brendan Haywood Jae Crowder Wilson Chandler Caron Butler Andrew Bogut Kentavious Caldwell- Kyrie Irving Monta Ellis -

Hawks Communications (404) 878-3800 # Truetoatlanta

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 9/20/19 CONTACT: Hawks Communications (404) 878-3800 ATLANTA - The Atlanta Hawks have re-signed guard/forward Vince Carter. Per team policy, terms of the agreement were not disclosed. Carter appeared in 76 games (nine starts) last season for the Hawks, averaging 7.4 points, 2.6 rebounds and 1.1 assists in 17.5 minutes (.419 FG%, .389 3FG%, .712 FT%). Through 21 seasons in the NBA with the Hawks, Toronto, New Jersey, Orlando, Phoenix, Dallas, Memphis and Sacramento, the 6’6” Carter has compiled averages of 17.2 points, 4.4 rebounds, 3.2 assists and 1.0 steals in 30.7 minutes (.437 FG%, .374 3FG%, .798 FT%). He’s also seen action in 88 postseason games (66 starts), averaging 18.1 points, 5.4 rebounds, 3.4 assists and 1.1 steals in 34.5 minutes (.416 FG%, .338 3FG%, .796 FT%). When Carter appears in his first regular season game in 2019-20, he will become the first player in NBA history to play in 22 seasons, and when he plays a game in 2020, will be the first player in league history to play in a game in four decades. Following are Carter’s statistical rankings amongst active players, and in NBA history: Statistical Category Total Active Rank Trailing: All-Time Rank Trailing: Games Played 1,481 1st -- 5th John Stockton (1,504) Field Goals Made 9,186 2nd LeBron James (11,838) 20th Moses Malone (9,435) Minutes Played 45,491 2nd LeBron James (46,235) 18th Robert Parish (45,704) Three-Point Field Goals Made 2,229 3rd Kyle Korver (2,351) 6th Jason Terry (2,282) Points 25,430 3rd Carmelo Anthony (25,551) 20th Carmelo Anthony (25,551) Steals 1,507 5th Trevor Ariza (1,515) 46th Julius Erving (1,508) Free Throws Made 4,829 6th Dwight Howard (5,034) 39th Kevin Garnett (4,887) Carter was the 1999 NBA Rookie of the Year, has been named All-NBA twice (second team in 2001 and third team in 2000), is an eight-time All-Star and finished in the Top 10 in scoring six times. -

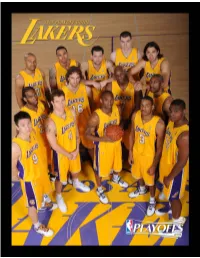

2008-09 Playoff Guide.Pdf

▪ TABLE OF CONTENTS ▪ Media Information 1 Staff Directory 2 2008-09 Roster 3 Mitch Kupchak, General Manager 4 Phil Jackson, Head Coach 5 Playoff Bracket 6 Final NBA Statistics 7-16 Season Series vs. Opponent 17-18 Lakers Overall Season Stats 19 Lakers game-By-Game Scores 20-22 Lakers Individual Highs 23-24 Lakers Breakdown 25 Pre All-Star Game Stats 26 Post All-Star Game Stats 27 Final Home Stats 28 Final Road Stats 29 October / November 30 December 31 January 32 February 33 March 34 April 35 Lakers Season High-Low / Injury Report 36-39 Day-By-Day 40-49 Player Biographies and Stats 51 Trevor Ariza 52-53 Shannon Brown 54-55 Kobe Bryant 56-57 Andrew Bynum 58-59 Jordan Farmar 60-61 Derek Fisher 62-63 Pau Gasol 64-65 DJ Mbenga 66-67 Adam Morrison 68-69 Lamar Odom 70-71 Josh Powell 72-73 Sun Yue 74-75 Sasha Vujacic 76-77 Luke Walton 78-79 Individual Player Game-By-Game 81-95 Playoff Opponents 97 Dallas Mavericks 98-103 Denver Nuggets 104-109 Houston Rockets 110-115 New Orleans Hornets 116-121 Portland Trail Blazers 122-127 San Antonio Spurs 128-133 Utah Jazz 134-139 Playoff Statistics 141 Lakers Year-By-Year Playoff Results 142 Lakes All-Time Individual / Team Playoff Stats 143-149 Lakers All-Time Playoff Scores 150-157 MEDIA INFORMATION ▪ ▪ PUBLIC RELATIONS CONTACTS PHONE LINES John Black A limited number of telephones will be available to the media throughout Vice President, Public Relations the playoffs, although we cannot guarantee a telephone for anyone. -

Pictured Aboved Are Two of UCLA's Greatest Basketball Figures – on The

Pictured aboved are two of UCLA’s greatest basketball figures – on the left, Lew Alcindor (now Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) alongside the late head coach John R. Wooden. Alcindor helped lead UCLA to consecutive NCAA Championships in 1967, 1968 and 1969. Coach Wooden served as the Bruins’ head coach from 1948-1975, helping UCLA win 10 NCAA Championships in his 24 years at the helm. 111 RETIRED JERSEY NUMBERS #25 GAIL GOODRICH Ceremony: Dec. 18, 2004 (Pauley Pavilion) When UCLA hosted Michigan on Dec. 18, 2004, Gail Goodrich has his No. 25 jersey number retired, becoming the school’s seventh men’s basketball player to achieve the honor. A member of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, Goodrich helped lead UCLA to its first two NCAA championships (1964, 1965). Notes on Gail Goodrich A three-year letterman (1963-65) under John Wooden, Goodrich was the leading scorer on UCLA’s first two NCAA Championship teams (1964, 1965) … as a senior co-captain (with Keith Erickson) and All-America selection in 1965, he averaged a team-leading 24.8 points … in the 1965 NCAA championship, his then-title game record 42 points led No. 2 UCLA to an 87-66 victory over No. 1 Michigan … as a junior, with backcourt teammate and senior Walt Hazzard, Goodrich was the leading scorer (21.5 ppg) on a team that recorded the school’s first perfect 30-0 record and first-ever NCAA title … a two-time NCAA Final Four All-Tournament team selection (1964, 1965) … finished his career as UCLA’s all-time leader scorer (1,690 points, now No. -

Pac-10 in the Nba Draft

PAC-10 IN THE NBA DRAFT 1st Round picks only listed from 1967-78 1982 (10) (order prior to 1967 unavailable). 1st 11. Lafayette Lever (ASU), Portland All picks listed since 1979. 14. Lester Conner (OSU), Golden State Draft began in 1947. 22. Mark McNamara (CAL), Philadelphia Number in parenthesis after year is rounds of Draft. 2nd 41. Dwight Anderson (USC), Houston 3rd 52. Dan Caldwell (WASH), New York 1967 (20) 65. John Greig (ORE), Seattle 1st (none) 4th 72. Mark Eaton (UCLA), Utah 74. Mike Sanders (UCLA), Kansas City 1968 (21) 7th 151. Tony Anderson (UCLA), New Jersey 159. Maurice Williams (USC), Los Angeles 1st 11. Bill Hewitt (USC), Los Angeles 8th 180. Steve Burks (WASH), Seattle 9th 199. Ken Lyles (WASH), Denver 1969 (20) 200. Dean Sears (UCLA), Denver 1st 1. Lew Alcindor (UCLA), Milwaukee 3. Lucius Allen (UCLA), Seattle 1983 (10) 1st 4. Byron Scott (ASU), San Diego 1970 (19) 2nd 28. Rod Foster (UCLA), Phoenix 1st 14. John Vallely (UCLA), Atlanta 34. Guy Williams (WSU), Washington 16. Gary Freeman (OSU), Milwaukee 45. Paul Williams (ASU), Phoenix 3rd 48. Craig Ehlo (WSU), Houston 1971 (19) 53. Michael Holton (UCLA), Golden State 1st 2. Sidney Wicks (UCLA), Portland 57. Darren Daye (UCLA), Washington 9. Stan Love (ORE), Baltimore 60. Steve Harriel (WSU), Kansas City 11. Curtis Rowe (UCLA), Detroit 5th 109. Brad Watson (WASH), Seattle (Phil Chenier (CAL), taken by Baltimore 7th 143. Dan Evans (OSU), San Diego in 1st round of supplementary draft for 144. Jacque Hill (USC), Chicago hardship cases) 8th 177. Frank Smith (ARIZ), Portland 10th 219. -

Basketball Packet # 4 Instructions

BASKETBALL PACKET # 4 INSTRUCTIONS This Learning Packet has two parts: (1) text to read and (2) questions to answer. The text describes a particular sport or physical activity, and relates its history, rules, playing techniques, scoring, notes and news. The Response Forms (questions and puzzles) check your understanding and appreciation of the sport or physical activity. INTRODUCTION Basketball is an extremely popular sport. More people watch basketball than any other sport in the United States. It is played in driveways, parking lots, back yards, streets, high schools, colleges and professional arenas. Basketball’s popularity is not confi ned to the United States. The game is also enjoyed internationally, with rules available in thirty languages. Basketball is included among the Olympic sports. HISTORY OF THE GAME In 1891, a physical education instructor at a YMCA Training School in Massachusetts invented basketball as an indoor activity for boys. The game began with two peach baskets tied to balconies and a soccer ball used to shoot baskets. Two years later, two college teams began to play basketball. The game’s popularity has increased continuously ever since. The National Basketball Association (NBA) is the larg- est professional sports league. It was created when the Basketball Association of America and the National Basketball League merged in 1949. The majority of professional players are recruited by the NBA from col- lege ranks. Physical Education Learning Packets #4 Basketball Text © 2009 The Advantage Press, Inc. HOW THE GAME IS PLAYED GENERAL PLAYING RULES The game of basketball is easy to understand. Players try to prevent their opponents from scoring while each team tries to get the ball through the basket that the other team is defending. -

Pac-12 NBA Draft History

NATIONAL HONORS PAC-12 IN THE NBA DRAFT Draft began in 1947. 1st Round picks only listed 1980 (10) 1984 (10) from 1967-78 (order prior to 1967 unavailable). 1st 11. Kiki Vandeweghe (UCLA), Dallas 1st 13. Jay Humphries (COLO), Phoenix All picks listed since 1979. 18. Don Collins (WSU), Atlanta 21. Kenny Fields (UCLA), Milwaukee Number in parenthesis after year is rounds of Draft. 2nd 42. Kimberly Belton (STAN), Phoenix 2nd 29. Stuart Gray (UCLA), Indiana 3rd 47. Kurt Nimphius (ASU), Denver 38. Charles Sitton (OSU), Dallas 1967 (20) 50. James Wilkes (UCLA), Chicago 4th 71. Ralph Jackson (UCLA), Indiana 1st (none) 53. Stuart House (WSU), Cleveland 92. John Revelli (STAN), LA Lakers 65. Doug True (CAL), Phoenix 6th 138. Keith Jones (STAN), LA Lakers 1968 (21) 5th 95. Don Carfno (USC), Golden State 7th 141. Butch Hays (CAL), Chicago 1st 11. Bill Hewitt (USC), Los Angeles 103. Darrell Allums (UCLA), Dallas 144. David Brantley (ORE), Clippers 6th 134. Coby Leavitt (UTAH), Phoenix 146. Michael Pitts (CAL), San Antonio 1969 (20) 7th 141. Lorenzo Romar (WASH), Golden State 152. Gary Gatewood (ORE), Seattle 1st 1. Lew Alcindor (UCLA), Milwaukee 148. Greg Sims (UCLA), Portland 8th 177. Chris Winans (UTAH), New Jersey 3. Lucius Allen (UCLA), Seattle 152. Joe Nehls (ARIZ), Houston 1985 (Seven) 1970 (19) 1981 (10) 1st 8. Detlef Schrempf (WASH), Dallas 1st 14. John Vallely (UCLA), Atlanta 1st 7. Steve Johnson (OSU), Kansas City 15. Blair Rasmussen (ORE), Denver 16. Gary Freeman (OSU), Milwaukee 5. Danny Vranes (UTAH), Seattle 23. A.C. Green (OSU), LA Lakers 8. -

How to Win a Title by the L.A. Lakers the 1

how to wIn a tItLe By the L.a. Lakers The 1. You need to play as a team. In our system, everyone can make decisions with the ball, but if we get too competitive, we can sometimes lose sight of the basics. I’ve figured out when to get guys involved and when to take over. These last two years, having better teammates makes that balance easier—they make me look better than I actually HOW-TO am.—koBe Bryant 2. Team defense is very important. There’s a difference between playing confident and playing cocky. You can’t always play for the blocked shot. You make them try to beat you from the perimeter.—LaMar odoM 3. Staying healthy is a blessing if you can do it, but it’s one of those things you can’t control. With conditioning, you do what Issue works best for you. I do a lot of yoga to stay flexible, and I’ve been running more sprints. I rarely touch weights. I’ve had two injuries and neither one was my fault.—andrew BynuM 4. You need motivated leadership. We have guys like Kobe and Fisher who keep pushing the envelope with the other guys. Our biggest challenge with players is how they handle adversity. That’s when we work really hard on keeping guys as sharp as possible, so that adversity, when it comes, becomes motivation.—phIL Jackson 1. 2. BackBack forfor MoreMore 3. 4. In the cIty that Made repeatIng faMous, It’s not hard to fIgure out what’s on the MInd of thIs year’s Lakers. -

2011-12 Season 2011-12 Season

2011-12 season 2011-12 season 2011-12 SEASON 66 2011-12 season 2011-12 season Record: 21-45 West: 14-34 East: 7-11 Division: 3-11 Home: 11-22 Road: 10-23 Overtime: 1-3 2011-12 Final Roster No. Player Position Height Weight Birthdate College/Country Yrs Pro 0 Al-Farouq Aminu F 6-9 215 Sept. 21, 1990 Wake Forest/USA 2 1 Trevor Ariza G/F 6-8 210 June 30, 1985 UCLA/USA 8 15 Gustavo Ayon F/C 6-10 250 Apr. 1, 1985 Fuenlabrada/Mexico 1 8 Marco Belinelli G 6-5 195 Mar. 25, 1986 Fortitudo Bologna/Italy 5 11 Jerome Dyson G 6-3 180 Mar. 1, 1987 Connecticut/USA 1 10 Eric Gordon G 6-3 215 Dec. 25, 1988 Indiana/USA 4 4 Xavier Henry G 6-6 220 Mar. 15, 1991 Kansas/USA 2 2 Jarrett Jack G 6-3 197 Oct. 28, 1983 Georgia Tech/USA 7 35 Chris Kaman C 7-0 265 Apr. 28, 1982 Central Michigan/USA 9 24 Carl Landry F 6-9 248 Sept. 19, 1983 Purdue/USA 5 50 Emeka Okafor C 6-10 255 Sept. 28, 1982 Connecticut/USA 8 14 Jason Smith F/C 7-0 240 Mar. 2, 1986 Colorado State/USA 4 42 Lance Thomas F 6-8 225 Apr. 24, 1988 Duke/USA 1 21 Greivis Vasquez G 6-6 211 Jan. 16, 1987 Maryland/Venezuela 2 31 Darryl Watkins C 6-11 258 Nov. 8, 1984 Syracuse/USA 2 Head Coach: Monty Williams, Notre Dame Lead Assistant Coach: Randy Ayers, Miami (Ohio) Assistant Coaches: James Borrego, San Diego; Dave Hanners, North Carolina; Bryan Gates, Boise State; Fred Vinson, Georgia Tech Trainer: John Ishop, Texas 2011-12 Final Statistics Player G GS MIN FG FGA PCT 3FG 3FGA PCT FT FTA PCT OFF DEF TOT AST PF DQ STL TO BLK PTS AVG Gordon 9 9 310 63 140 .450 10 40 .250 49 65 .754 2 23 25 31 20 0 13 24 4