Sri Lanka Broadcast Media Report June – August 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Stations

1 CHANGING STATIONS FULL INDEX 100 Top Tunes 190 2GZ Junior Country Service Club 128 1029 Hot Tomato 170, 432 2HD 30, 81, 120–1, 162, 178, 182, 190, 192, 106.9 Hill FM 92, 428 247, 258, 295, 352, 364, 370, 378, 423 2HD Radio Players 213 2AD 163, 259, 425, 568 2KM 251, 323, 426, 431 2AY 127, 205, 423 2KO 30, 81, 90, 120, 132, 176, 227, 255, 264, 2BE 9, 169, 423 266, 342, 366, 424 2BH 92, 146, 177, 201, 425 2KY 18, 37, 54, 133, 135, 140, 154, 168, 189, 2BL 6, 203, 323, 345, 385 198–9, 216, 221, 224, 232, 238, 247, 250–1, 2BS 6, 302–3, 364, 426 267, 274, 291, 295, 297–8, 302, 311, 316, 345, 2CA 25, 29, 60, 87, 89, 129, 146, 197, 245, 277, 354–7, 359–65, 370, 378, 385, 390, 399, 401– 295, 358, 370, 377, 424 2, 406, 412, 423 2CA Night Owls’ Club 2KY Swing Club 250 2CBA FM 197, 198 2LM 257, 423 2CC 74, 87, 98, 197, 205, 237, 403, 427 2LT 302, 427 2CH 16, 19, 21, 24, 29, 59, 110, 122, 124, 130, 2MBS-FM 75 136, 141, 144, 150, 156–7, 163, 168, 176–7, 2MG 268, 317, 403, 426 182, 184–7, 189, 192, 195–8, 200, 236, 238, 2MO 259, 318, 424 247, 253, 260, 263–4, 270, 274, 277, 286, 288, 2MW 121, 239, 426 319, 327, 358, 389, 411, 424 2NM 170, 426 2CHY 96 2NZ 68, 425 2Day-FM 84, 85, 89, 94, 113, 193, 240–1, 243– 2NZ Dramatic Club 217 4, 278, 281, 403, 412–13, 428, 433–6 2OO 74, 428 2DU 136, 179, 403, 425 2PK 403, 426 2FC 291–2, 355, 385 2QN 76–7, 256, 425 2GB 9–10, 14, 18, 29, 30–2, 49–50, 55–7, 59, 2RE 259, 427 61, 68–9, 84, 87, 95, 102–3, 107–8, 110–12, 2RG 142, 158, 262, 425 114–15, 120–2, 124–7, 129, 133, 136, 139–41, 2SM 54, 79, 84–5, 103, 119, 124, -

United Kingdom Distribution Points

United Kingdom Distribution to national, regional and trade media, including national and regional newspapers, radio and television stations, through proprietary and news agency network of The Press Association (PA). In addition, the circuit features the following complimentary added-value services: . Posting to online services and portals with a complimentary ReleaseWatch report. Coverage on PR Newswire for Journalists, PR Newswire's media-only website and custom push email service reaching over 100,000 registered journalists from 140 countries and in 17 different languages. Distribution of listed company news to financial professionals around the world via Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg and proprietary networks. Releases are translated and distributed in English via PA. 3,298 Points Country Media Point Media Type United Adones Blogger Kingdom United Airlines Angel Blogger Kingdom United Alien Prequel News Blog Blogger Kingdom United Beauty & Fashion World Blogger Kingdom United BellaBacchante Blogger Kingdom United Blog Me Beautiful Blogger Kingdom United BrandFixion Blogger Kingdom United Car Design News Blogger Kingdom United Corp Websites Blogger Kingdom United Create MILK Blogger Kingdom United Diamond Lounge Blogger Kingdom United Drink Brands.com Blogger Kingdom United English News Blogger Kingdom United ExchangeWire.com Blogger Kingdom United Finacial Times Blogger Kingdom United gabrielleteare.com/blog Blogger Kingdom United girlsngadgets.com Blogger Kingdom United Gizable Blogger Kingdom United http://clashcityrocker.blogg.no Blogger -

DI-P02-18-10-( RE)-UWS.Qxd

2 Wednesday 18th October, 2006 Are you a lucky winner? DEVELOPMENT SUPIRI VASANA MAHAJANA SHRAMA VASANA SATURDAY JAYODA VASANA SAMPATHA GOVI SETHA SUWASETHA Draw No: 43 Draw No: 280 Draw No: 631 SAMPATHA FORTUNE SAMPATHA FORTUNE Draw Date: Date: Draw No: 823 Draw No.570 Draw Date: Draw No.365 Draw No: 1753 Draw Date: Draw Date: 15 - 10- 2006 08-10-2006 Draw Date: 16-10-2006 05-10-2006 17 - 10 - 2006 17-10-2006 Date: 14.10.2006 Date: 14-10-2006 Date: 09-10-2006 Draw No. 13 Winning Nos: Super No:24 Bonus No. 35 Draw No. 1863 Symbol:Taurus Winning Nos: Winnings Nos Winning Nos. 16-40-41-44 Winning Nos. Winning Nos : Winning Nos: Winning Nos. Winning Nos: 31 -45 - 56 - 67 26-40-44-47-57 Bonus No. 18 03-26-29-38 M- 01 - 06- 38- 63 Super No.15 5 8 3 0 1 3 09-15-52-55 V-22-51-55-68 W-55-33-33-88-22-99 SC judgement on N/E merger Jumbos... From page 1 said, adding, people that “whom we previously identified as Wickremesinghe loyalists batted for us.” The vast majority called for a partnership with the SLFP, the sources said. The sources claimed — JVP that their position was further strengthened by Mahinda A new chapter is turned Wijesekera’s backing. Wijesekera who vehemently opposed the by Harischandra Gunaratna the separatist elements and this while the Security Forces are hell Jayasuriya-led move backed by Dr. Rajitha Senaratne, changed The JVP yesterday said the gave some kind of recognition to bent on defeating terrorism and sides on Monday. -

South Bergen Fri Ends. Wish You a Happy '60 Leader

Ilttiem MdllUKMKOMW» South Bergen Fri ends. Wish You A Happy '60 ta t to. &x j « * s x ïsx «« ew b k a oilier in years nifi in ihf last week. They exrhaiiKed shame-faced .looks. Then thry l»f((an Leader Publications to tell their »¿yfilu rr» of traveling by Im»*. They told iiorrrndoii« stori«*»* of the long COMERCIAL LEADER .jJc h i y> raiis«*cl wlient*\i*r a -light m ish ap jaiiini«*«! NORTH ARLINGTON LEADER traili«* on tli«* hifjhwaVH. ^ Then they got into tin* warm. smoofh-run- LEADER FREE PRESS nifi” rail «ars an«l wrr«* shot into llnlmkcit vi iili- f'ut fu>s_or feathers. l*fthlishc<| e\«*r\ Thur-day I*\ III«* (.ommen ial Leader Priming < «unpan) at 2">l Ridge Road. I.vndhiirst. Y J. Telephone t,fcneva A instant Railroads KTol W hen the storm broke la-t week, «lumping •more snow than we have experience«! in two Yes Virginia ? vear-. the railroails went into a«*tion at once. They put to work gangs of hiimlre«ls «»f men T«» tin* jiood little girl w ith tin* spit c u rl w ho clearing the way. warming up the switches and aske«l last week if tlitre really. really are pas- making r«*a«ly for wliat«*\cr tin* storm might s«*nger trains, the answer i« an «»mphatic yes. bring. On last ..Monday aftern«M»n snow began to The buses waited for the government to fall. By the time darkness f«*ll the snow he<ame «*l«*aii th e highw ays. -

PE 2020 MR 82 S.Pdf

Election Commission – Sri Lanka Parliamentary Election - 05.08.2020 Registered electronic media to disseminate certified election results Last Updated Online Social Media No Organization TV FM Publishers(News Other News Websites (FB/ SMS Paper Web Sites) YouTube/ Twitter) 1 Telshan Network TNL TV - - - - - (Pvt) Ltd 2 Smart Network - - - www.lankasri.lk - - (Pvt) Ltd 3 Bhasha Lanka (Pvt) - - - www.helakuru.lk - - Ltd 4 Digital Content - - - www.citizen.lk - - (Pvt) Ltd 5 Ceylon News - - www.mawbima.lk, - - - Papers (Pvt) Ltd www.ceylontoday.lk Independent ITN, Lakhanda, www.itntv.lk, ITN Sri Lanka 6 Television Network Vasantham TV Vasantham - www.itnnews.lk (FB) - Ltd FM Lakhanda Radio (FB) Sri Lanka City FM 7 Broadcasting - - - - - Corporation (SLBC) Asia Broadcasting Hiru FM. 8 Corparation Hiru TV Shaa FM, www.hirunews.lk, Sooriyan FM, - www.hirugossip.lk - - Sun FM, Gold FM 9 Asset Radio Broadcasting (Pvt) - Neth FM - www.nethnews.lk NethFM(FB) - Ltd 1/4 File Online Number Organization TV FM Publishers(News Other News Websites Social Media SMS Paper Web Sites) Asian Media 10 Publications (Pvt) ltd - - www.thinakkural.lk - - - 11 EAP Broadcasting Swarnavahini Shree FM, - www.swarnavahini.lk, - - Company Ran FM www.athavannews.com 12 Voice of Asia Siyatha TV Siyatha FM - - - - Network (Pvt)Ltd Star tamil TV MTV Channel (Pvt) Sirasa TV, Sirasa FM, News 1st (FB), News 1st SMS 13 Ltd / MBC Shakthi TV, Shakthi FM, News 1st (S,T,E), Networks (Pvt) Ltd TV1 Yes FM, - www.newsfirst.lk (Youtube), KIKI mobile YFM, News 1st App Legends FM (Twitter) -

Monitoring Media Coverage of Presidential Election November 2005

24/2, 28t h La n e , Off Flowe r Roa d , Colom bo 7, Sri La n ka Tel: 94-11-2565304 / 94-11-256530z6 / 94-11-5552746, Fax: 94-11-4714460 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.cpalanka.org Media Unit Monitoring media coverage of Presidential election November 2005 Report No. 02 Compiled by Sunanda Deshapriya & Sisira Kannangara 8th-24th October Monitored news papers: 11 dailies, 17 weeklies Number of newspaper issues monitored: 205 State media - Monitored Newspapers: Dailies: Dinamina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran (Tamil language), Daily News (English language); W eeklies: Silumina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran Vaaramanjaree (Tamil language), Sunday Observer (English language); 1. The three state owned dailies - Dinamina, Thinakaran and Daily News - had the lowest Unfavorable coverage of total election coverage on Mahinda Rajapakse, respectively 1.04. 00.33% and 1.87%. 2. The same newspapers had the highest Favorable coverage given to any candidate by same language daily news paper, in these instances to Mahinda R. - Dinamina (50.61%), Thinakaran (59.70%) and Daily News (38.18%) 3. The three state dailies had the highest Unfavorable coverage of the Ranil W ickramasinghe of except daily DIvaina (7.05%). Dinamina had 29.46%. Thinkaran had 10.30% and Daily News had 06.21%. Their Favorable coverage of Ranil W ickramasinghe was 08.26%, 5.11% and 09.18% respectively. 4. The state owned dailies and weeklies had 17 front page Lead stories and 09 Editorials in favor of Mahinda Rajapakse, while 08 Editorials and 03 front page Lead stories were Unfavorable to Ranil Wickramasinghe. Monitoring Presidential Election Coverage Nov. -

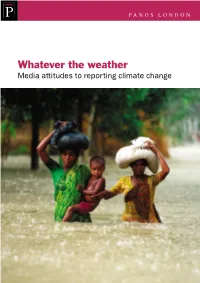

6. Whatever the Weather. Media Attitudes to Reporting Climate Change

PANOS LONDON Whatever the weather Media attitudes to reporting climate change Contents 1 Climate change and the media 1 Global policy on climate change 2 Carbon trading standards 3 The survey 4 Key findings 4 Recommendations 6 2 Case studies 7 Honduras 7 Jamaica 10 Sri Lanka 12 Zambia 14 Cover: © Panos London, 2006 Villagers returning with relief aid through heavy rains. Monsoon Panos London is part of a worldwide rains caused flooding in 40 network of independent NGOs working of Bangladesh’s 64 districts, displacing up to 30 million people with the media to stimulate debate and killing several hundred. on global development. GMB AKASH/PANOS PICTURES All photographs available from Panos Pictures www.panos.co.uk For further information contact: Environment Programme Written by Rod Harbinson with Panos London case studies by Dr Richard Mugara 9 White Lion Street (Zambia) and Ambika Chawla London N1 9PD (Sri Lanka, Jamaica and Honduras). United Kingdom Thanks to Panos Caribbean and Panos Southern Africa for Tel: +44(0)20 7278 1111 their contribution. Fax: +44(0)20 7278 0345 Designed by John F McGill [email protected] Printed by Digital-Brookdale www.panos.org.uk/environment Whatever the weather: media attitudes to reporting climate change 1 Climate change and the media 1 YOLA MONAKHOV/PANOS PICTURES The media play an important role in stimulating discussion in developing countries. Yet journalists asked by Panos say that the media have a poor understanding of the climate change debate and express little interest in it. Public discussion of the policies and issues involved is urgently needed. -

PDF995, Job 7

24/2, 28t h La n e , Off Flowe r Roa d , Colom bo 7, Sri La n ka Tel: 94-11-2565304 / 94-11-256530z6 / 94-11-5552746, Fax: 94-11-4714460 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.cpalanka.org Media Unit Monitoring media coverage of Presidential election November 2005 Compiled by Sunanda Deshapriya & Sisira Kannangara First week from nomination: 8th-15th October Monitored news papers: 11 dailies, 17 weeklies Number of newspaper issues monitored: 94 State media - Monitored Newspapers: Dailies: Dinamina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran (Tamil language), Daily News (English language); W eeklies: Silumina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran Vaaramanjaree (Tamil language), Sunday Observer (English language); • The three state owned dailies - Dinamina, Thinakaran and Daily News - had the lowest Unfavorable coverage of total election coverage on Mahinda Rajapakse, respectively 1.14, 00% and 1.82%. The same newspapers had the highest Favorable coverage given to any candidate by same language daily news paper, in these instances to Mahinda Rajapakse. - Dinamina (43.56%), Thinakaran (56.21%) and Daily News (29.32%). • The three state dailies had the highest Unfavorable coverage of the Ranil W ickramasinghe, of any daily news paper. Dinamina had 28.82%. Thinkaran had 8.67% and Daily News had 12.64%. • Their Favorable coverage of Ranil W ickramasinghe, was 10.75%, 5.10% and 11.13% respectively. • The state owned dailies and weeklies had 04 front page Lead stories and 02 Editorials in favor of Mahinda Rajapakse, while 02 Editorials and 03 front page Lead stories were Unfavorable to Ranil Wickramasinghe. State media coverage of two main candidates (in sq.cm% of total election coverage) Mahinda Rajapakshe Ranil W ickramasinghe Newspaper Favorable Unfavorable Favorable Unfavorable Dinamina 43.56 1.14 10.75 28.88 Silumina 28.82 10.65 18.41 30.65 Daily news 29.22 1.82 11.13 12.64 Sunday Observer 23.24 00 12.88 00.81 Thinakaran 56.21 00 03.41 00.43 Thi. -

The Sri Lankan Insurgency: a Rebalancing of the Orthodox Position

THE SRI LANKAN INSURGENCY: A REBALANCING OF THE ORTHODOX POSITION A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Peter Stafford Roberts Department of Politics and History, Brunel University April 2016 Abstract The insurgency in Sri Lanka between the early 1980s and 2009 is the topic of this study, one that is of great interest to scholars studying war in the modern era. It is an example of a revolutionary war in which the total defeat of the insurgents was a decisive conclusion, achieved without allowing them any form of political access to governance over the disputed territory after the conflict. Current literature on the conflict examines it from a single (government) viewpoint – deriving false conclusions as a result. This research integrates exciting new evidence from the Tamil (insurgent) side and as such is the first balanced, comprehensive account of the conflict. The resultant history allows readers to re- frame the key variables that determined the outcome, concluding that the leadership and decision-making dynamic within the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) had far greater impact than has previously been allowed for. The new evidence takes the form of interviews with participants from both sides of the conflict, Sri Lankan military documentation, foreign intelligence assessments and diplomatic communiqués between governments, referencing these against the current literature on counter-insurgency, notably the social-institutional study of insurgencies by Paul Staniland. It concludes that orthodox views of the conflict need to be reshaped into a new methodology that focuses on leadership performance and away from a timeline based on periods of major combat. -

His Holiness Pope Francis Visits Sri Lanka

February 2015 NEWS SRI LANKA Embassy of Sri Lanka, Washington DC FOREIGN MINISTER SAMARAWEERA CONCLUDES SUCCESSFUL VISIT TO THE US CAPITAL to strengthen US-Sri Lanka bilateral relations and future steps to be taken to achieve envisaged objectives. Inviting Secretary Kerry to visit Sri Lanka at an appropriate time, Minister Sa- maraweera stressed that he looks forward to working closely with the Secretary of State and other important partners in the United States to enhance relations between the two coun- tries to a state of excellence. Addressing a full house at the Carnegie Endowment for In- ternational Peace, the oldest international affairs think-tank in the US, after warm welcome remarks by its newly ap- pointed President, the former US Deputy Secretary of State Ambassador William J. Burns, the Minister spoke at length on the post-Presidential election developments in the coun- try including steps being taken for reconciliation, strengthen- ing democracy and good governance and also set out foreign policy objectives of the Government. Speaking on Sri Lanka-US Relations at the National Press Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera visited Washington Club, the Minister observed that shared values and commit- DC from 11-12 February. The visit which was his first to the ment to democratic ideals gives much scope for the two coun- US capital since assuming office as the Minister of Foreign tries to work together and that the Sri Lanka – US partnership Affairs followed the visit of US Assistant Secretary of State Ni- must take into account the island’s strategic geographic loca- sha Biswal to Colombo on 2-3 February and coincided with tion. -

214908890.Pdf

The Indian Premier League (IPL) is an Indian professional league for men's Twenty20 cricket clubs with double round- robin and playoffs. Without any Twenty20 cricket league system, it is India's primary Twenty20 cricket club competition. Currently contested by eight clubs, it does not operates on a system of promotion and relegation. Only Indian clubs are qualify to play in the Premier League. Seasons run in the Indian summer spanning between April and June, with most games are played in the afternoons. The competition was formed by the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) in 2008 after an altercation between the BCCI and the now-defunct Indian Cricket League.[1] The Premier League is headquartered in Mumbai,Maharashtra,[2][3] and is currently supervised by BCCI Vice-President Ranjib Biswal, who serves as the League's Chairman and Commissioner.[4] The Premier League is the most-watched Twenty20 cricket league in the world. It is generally considered to be the highest- profile showcase in the world for Twenty20 club cricket, the shortest form of professional cricket with just 20overs per innings. IPL is as well known for its commercial success and for the quality of Twenty20 cricket played. During the sixth IPL season (2013) its brand value was estimated to be around US$3.03 billion.[5][6] Live rights to the event are syndicated around the globe, and in 2010, the IPL became the first sporting event to be broadcast live on YouTube.[7] It is currently sponsored by Pepsi and thus officially known as the Pepsi Indian Premier League.[8] Two eligible bids were received, with Pepsi winning over Airtel with a bid of 3968 million.[9]However, the League has been the subject of several controversies where allegations of cricket betting, money laundering and spot fixing were witnessed.[10][11] Of the 11 clubs to have competed since the inception of the Premier League in 2008, five have won the title:Chennai Super Kings (2), Rajasthan Royals (1), Deccan Chargers (1), Kolkata Knight Riders (1) and Mumbai Indians (1). -

Order Paper of November 28, 2006

[ Sixth Parliament - Second Session] No. 78.] ORDER PAPER OF PARLIAMENT FOR Tuesday, November 28, 2006 at 9.30 a.m. QUESTIONS FOR ORAL ANSWERS 0679/’06 1. Hon. Tissa Attanayake,— To ask the Minister of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources,—(1) (a) Will he inform separately to this House, the names of advisors appointed to the Ministry of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources and to the Institutions, Statutory Boards and Corporations which come under the Ministry? (b) Will he state separately— (i) the basis on which they were appointed, (ii) their qualifications; (iii) the salaries and allowances paid to them and other facilities enjoyed by them as advisors; and (iv) the duties that have been entrusted to them? (c) If not, why? 0680/’06 2. Hon. Tissa Attanayake,— To ask the Minister of Foreign Employment Promotion and Deputy Minister of Post and Telecommunication,—(1) (a) Will he inform separately to this House, the names of advisors appointed to the Ministry of Foreign Employment Promotion and to the Institutions, Statutory Boards and Corporations which come under the Ministry? (b) Will he state separately— (i) the basis on which they were appointed, (ii) their qualifications; ( 2 ) (iii) the salaries and allowances paid to them and other facilities enjoyed by them as advisors; and (iv) the duties that have been entrusted to them? (c) If not, why? 0220/’06 3. Hon. Vijitha Ranaweera,— To ask the Minister of Samurdhi and Poverty Alleviation,—(4) (a) Will she submit to this House the names and addresses of the Samurdhi recipients in the Katuwana Divisional