West Papua: the Issue That Won't Go Away for Melanesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49128-0 — Democracy and Nationalism in Southeast Asia Jacques Bertrand Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49128-0 — Democracy and Nationalism in Southeast Asia Jacques Bertrand Index More Information Index 1995 Mining Law, 191 Authoritarianism, 4, 11–13, 47, 64, 230–31, 1996 Agreement (with MNLF), 21, 155–56, 232, 239–40, 245 157–59, 160, 162, 165–66 Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao, 142, 150, 153, 157, 158–61, 167–68 Abu Sayaff, 14, 163, 170 Autonomy, 4, 12, 25, 57, 240 Accelerated development unit for Papua and Aceh, 20, 72, 83, 95, 102–3, 107–9 West Papua provinces, 131 Cordillera, 21, 175, 182, 186, 197–98, 200 Accommodation. See Concessions federalism, 37 Aceh Peace Reintegration Agency, 99–100 fiscal resources, 37 Aceh Referendum Information Centre, 82, 84 fiscal resources, Aceh, 74, 85, 89, 95, 98, Aceh-Nias Rehabilitation and Reconstruction 101, 103, 105 Agency, 98 fiscal resources, Cordillera, 199 Act of Free Choice, 113, 117, 119–20, 137 fiscal resources, Mindanao, 150, 156, 160 Administrative Order Number 2 (Cordillera), fiscal resources, Papua, 111, 126, 128 189–90, See also Ancestral domain Indonesia, 88 Al Hamid, Thaha, 136 jurisdiction, 37 Al Qaeda, 14, 165, 171, 247 jurisdiction, Aceh, 101 Alua, Agus, 132, 134–36 jurisdiction, Cordillera, 186 Ancestral Domain, 166, 167–70, 182, 187, jurisdiction, Mindanao, 167, 169, 171 190, 201 jurisdiction, Papua, 126 Ancestral Land, 184–85, 189–94, 196 Malay-Muslims, 22, 203, 207, 219, 224 Aquino, Benigno Jr., 143, 162, 169, 172, Mindanao, 20, 146, 149, 151, 158, 166, 172 197, 199 Papua, 20, 122, 130 Aquino, Butz, 183 territorial, 27 Aquino, Corazon. See Aquino, Cory See also Self-determination Aquino, Cory, 17, 142–43, 148–51, 152, Azawad Popular Movement, Popular 180, 231 Liberation Front of Azawad (FPLA), 246 Armed Forces, 16–17, 49–50, 59, 67, 233, 236 Badan Reintegrasi Aceh. -

Smuggling Cultures in the Indonesia-Singapore Borderlands

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Amsterdam University Press as: Ford, M., Lyons, L. (2012). Smuggling Cultures in the Indonesia-Singapore Borderlands. In Barak Kalir and Malini Sur (Eds.), Transnational Flows and Permissive Polities: Ethnographies of Human Mobilities in Asia, (pp. 91-108). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. Smuggling Cultures in the Indonesia-Singapore Borderlands Michele Ford and Lenore Lyons The smuggling will never stop. As long as seawater is still seawater and as long as the sea still has water in it, smuggling will continue in the Riau Islands. Tengku Umar, owner of an import-export business Borders are lucrative zones of exchange and trade, much of it clandestine. Smuggling, by definition, 'depends on the presence of a border, and on what the state declares can be legally imported or exported' (Donnan & Wilson 1999: 101), and while free trade zones and growth triangles welcome the free movement of goods and services, border regions can also become heightened areas of state control that provide an environment in which smuggling thrives. Donnan and Wilson (1999: 88) argue that acts of smuggling are a form of subversion or resistance to the existence of the border, and therefore the state. However, there is not always a conflict of interest and struggle between state authorities and smugglers (Megoran, Raballand, & Bouyjou 2005). Synergies between the formal and informal economies ensure that illegal cross-border trade does not operate independently of systems of formal regulatory authority. -

Heads of State Heads of Government Ministers For

UNITED NATIONS HEADS OF STATE Protocol and Liaison Service HEADS OF GOVERNMENT PUBLIC LIST MINISTERS FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS COUNTRY HEAD OF STATE HEAD OF GOVERNMENT MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS AFGHANISTAN His Excellency Same as Head of State His Excellency Mr. Mohammad Ashraf Ghani Mr. Mohammad Haneef Atmar Full Title President of the Islamic Republic of Acting Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Afghanistan Republic of Afghanistan Date of Appointment 29-Sep-14 04-Apr-20 ALBANIA His Excellency His Excellency same as Prime Minister Mr. Ilir Meta Mr. Edi Rama Full Title President of the Republic of Albania Prime Minister and Minister for Europe and Foreign Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs of the Affairs of the Republic of Albania Republic of Albania Date of Appointment 24-Jul-17 15-Sep-13 21-Jan-19 ALGERIA Son Excellence Son Excellence Son Excellence Monsieur Abdelmadjid Tebboune Monsieur Abdelaziz Djerad Monsieur Sabri Boukadoum Full Title Président de la République algérienne Premier Ministre de la République algérienne Ministre des Affaires étrangères de la République démocratique et populaire démocratique et populaire algérienne démocratique et populaire Date of Appointment 19-Dec-19 05-Jan-20 31-Mar-19 21/08/2020 Page 1 of 66 COUNTRY HEAD OF STATE HEAD OF GOVERNMENT MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS ANDORRA Son Excellence Son Excellence Son Excellence Monseigneur Joan Enric Vives Sicília Monsieur Xavier Espot Zamora Madame Maria Ubach Font et Son Excellence Monsieur Emmanuel Macron Full Title Co-Princes de la Principauté d’Andorre Chef du Gouvernement de la Principauté d’Andorre Ministre des Affaires étrangères de la Principauté d’Andorre Date of Appointment 16-May-12 21-May-19 17-Jul-17 ANGOLA His Excellency His Excellency Mr. -

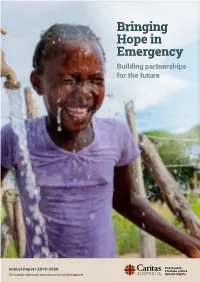

2019-2020 Annual Report

Bringing Hope in Emergency Building partnerships for the future Annual Report 2019-2020 The Catholica BRINGING Agency HOPE for IN EMERGENCYInternational Aid and Development “The Spirit of the Lord is Contents upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good Our Vision news to the poor. He has Vision and Mission 1 sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery From the Chair 2 of sight to the blind, to let From the CEO 3 the oppressed go free, to Principles 4 proclaim the year of the Strategy 5 Lord’s favour.” Our Work Luke 4:17-19 Where we work 6-7 Myanmar 8 Australia 9 Lebanon 10 South Sudan 11 Solomon Islands 12 Vietnam 13 Evaluation and learning 14 COVID-19 response 15 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be aware that this publication may contain images or names of people who have since passed away. Caritas Our Year Australia acknowledges the traditional owners and custodians, past and present, of the land on which all our offices are located. Year in review 16-17 Our year in advocacy 18 Cover: Villagers in Afghanistan learn how to protect themselves from COVID-19 In their own words 19 through hand-washing and hygiene measures. Photo: Stefanie Glinski/Catholic Relief Services Financial snapshot 20-21 Inside cover: A child in the Turkana region of Kenya, an arid region and the poorest in Kenya, with 60% of the population living in extreme poverty. Photo: Garry Walsh, Trocaire Fundraising spotlight 22 Design: Three Blocks Left ABN 90 970 605 069 Published November 2020 by Caritas Australia © Copyright Caritas Australia 2020 Leadership ISSN 2201-3083 In keeping with Caritas Australia’s high standard of transparency, this version has Our Diocesan network 23 been updated to correct minor typographical errors from an earlier version. -

Initiating Bus Rapid Transit in Jakarta, Indonesia

Initiating Bus Rapid Transit in Jakarta, Indonesia John P. Ernst On February 1, 2004, a 12.9-km (8-mi) bus rapid transit (BRT) line began the more developed nations, the cities involved there frequently lack revenue operation in Jakarta, Indonesia. The BRT line has incorporated three critical characteristics more common to cities in developing most of the characteristics of BRT systems. The line was implemented in countries: only 9 months at a cost of less than US$1 million/km ($1.6 million/mi). Two additional lines are scheduled to begin operation in 2005 and triple 1. High population densities, the size of the BRT. While design shortcomings for the road surface and 2. Significant existing modal share of bus public transportation, terminals have impaired performance of the system, public reaction has and been positive. Travel time over the whole corridor has been reduced by 3. Financial constraints providing a strong political impetus to 59 min at peak hour. Average ridership is about 49,000/day at a flat fare reduce, eliminate, or prevent continuous subsidies for public transit of 30 cents. Furthermore, 20% of BRT riders have switched from private operation. motorized modes, and private bus operators have been supportive of expanding Jakarta’s BRT. Immediate improvements are needed in the These three characteristics combine to favor the development of areas of fiscal handling of revenues and reconfiguring of other bus routes. financially self-sustaining BRT systems that can operate without gov- The TransJakarta BRT is reducing transport emissions for Jakarta and ernment subsidy after initial government expenditures to reallocate providing an alternative to congested streets. -

The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua Before and After Reformasi

International Center for Transitional Justice The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua Before and After Reformasi June 2012 Cover: A Papuan victim shows diary entries from 1969, when he was detained and transported to Java before the Act of Free Choice. ICTJ International Center The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua for Transitional Justice Before and After Reformasi The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua Before and After Reformasi www.ictj.org iii International Center The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua for Transitional Justice Before and After Reformasi Acknowledgements The International Center for Transitional Justice and (ICTJ) and the Institute of Human Rights Studies and Advocacy (ELSHAM) acknowledges the contributions of Matthew Easton, Zandra Mambrasar, Ferry Marisan, Joost Willem Mirino, Dominggas Nari, Daniel Radongkir, Aiesh Rumbekwan, Mathius Rumbrapuk, Sem Rumbrar, Andy Tagihuma, and Galuh Wandita in preparing this paper. Editorial support was also provided by Tony Francis, Atikah Nuraini, Nancy Sunarno, Dodi Yuniar, Dewi Yuri, and Sri Lestari Wahyuningroem. Research for this document were supported by Canada Fund. This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of ICTJ and ELSHAM and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. About the International Center for Transitional Justice ICTJ works to assist societies in regaining humanity in the wake of massive human rights abuses. We provide expert technical advice, policy analysis, and comparative research on transitional justice approaches, including criminal prosecutions, reparations initiatives, truth seeking and memory, and institutional reform. -

The Southwest Pacific: U.S

Order Code RL34086 The Southwest Pacific: U.S. Interests and China’s Growing Influence July 6, 2007 Thomas Lum Specialist in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Bruce Vaughn Specialist in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division The Southwest Pacific: U.S. Interests and China’s Growing Influence Summary This report focuses on the 14 sovereign nations of the Southwest Pacific, or Pacific Islands region, and the major external powers (the United States, Australia, New Zealand, France, Japan, and China). It provides an explanation of the region’s main geographical, political, and economic characteristics and discusses United States interests in the Pacific and the increased influence of China, which has become a growing force in the region. The report describes policy options as considered at the Pacific Islands Conference of Leaders, held in Washington, DC, in March 2007. Although small in total population (approximately 8 million) and relatively low in economic development, the Southwest Pacific is strategically important. The United States plays an overarching security role in the region, but it is not the only provider of security, nor the principal source of foreign aid. It has relied upon Australia and New Zealand to help promote development and maintain political stability in the region. Key components of U.S. engagement in the Pacific include its territories (Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa), the Freely Associated States (Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau), military bases on Guam and Kwajalein atoll (Marshall Islands), and relatively limited aid and economic programs. Some experts argue that U.S. involvement in the Southwest Pacific has waned since the end of the Cold War, leaving a power vacuum, and that the United States should pay greater attention to the region and its problems. -

Accept Corona As Part of Life, Return to Normalcy

Indian Horizon National English Daily [email protected] www.indianhorizon.org RNI NO: DELENG/2013/51507 In memory of Dr Asima Kemal and Prof. Dr. Salim W Kemal [email protected] Volume Issue No: 139 Published from New Delhi & Hyderabad New Delhi, Thursday, May 21, 2020 No: 7 Pages 12 + 4 pull out (P16) Price: 3.00 INS TO SC: CENTRE, STATES TOOK HCQ AFTER VALET MAIN AIM IS TO WIN AN OLY OWE SEVERAL CRORES’ DUES TESTED COVID POSITIVE, MEDAL OF DIFFERENT COLOUR TO MEDIA INDUSTRY SAYS TRUMP IN TOKYO: MARY P-3 P-8 P-11 HOLIDAY NOTICE New Delhi, May 20 (IANS) mentation of the scheme that Prime Minister Narendra Modi NARENDRA MODI : is expected to bring about Blue THE WORLD UNDER ATTACK on Wednesday said several de- Revolution through sustainable cisions taken by the Cabinet Migrants, fishermen, and responsible development SCOURGE OF CORONAVIRUS today focused on welfare of of fisheries sector in India un- migrants, poor and senior citi- senior citizen to gain from der two components -- Central zens, adding these would facili- Sector Scheme and Centrally TOTAL TALLY IN INDIA Our office will be tate easier availability of credit Cabinet decisions Sponsored Scheme -- at a to- mounts to 1,06,750, death closed on 21st of May, and create opportunities in the tal estimated investment of Rs 2020 on the occasion fisheries sector. equate livelihood for rural-ur- 20,050 crore. toll 3,303 of Shab-E-Qadr. While welcoming the Cabi- ban communities.On ‘Pradhan The scheme is likely to ad- Therefore, net’s decision on formalisation Mantri Matsya Sampada Yo- dress the critical gaps in the of microfood processing enter- jana’, Modi said it will “revolu- fisheries sector and realize its there will be no issue prises, PM Modi tweeted: “The tionise the fisheries sector”. -

Seakan Kitorang Setengah Binatang RASIALISME INDONESIA DI TANAH PAPUA

Filep Karma adalah pemimpin paling berani di Papua Barat. Dia lawan kekerasan dengan taktik non-kekerasan macam Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King dan Nelson Mandela. Eben Kirksey, antropolog, menulis buku “Freedom in Entangled Worlds: West Papua and the Architecture of Global Power” Filep Karma’s steadfast resistance is an inspiration to all those struggling for human rights and justice for West Papua and elsewhere. John M. Miller, koordinator East Timor and Indonesia Action Network di New York Filep Karma is known to many in New Zealand. He is an icon of commit- ment to justice and freedom. Maire Leadbeater dari Auckland Aotearoa menulis buku “Negligent Neighbour: New Zealand’s Complicity in the Invasion and Occupation of Timor-Leste” Seakan Kitorang Setengah BinAtang RASIALISME INDONESIA DI TANAH PAPUA FILEP KARMA Seakan Kitorang Setengah Binatang Rasialisme Indonesia di Tanah Papua ©Deiyai Cetakan Pertama, November 2014 Interviewer Basilius Triharyanto Firdaus Mubarik Ruth Ogetay Nona Elisabeth Editor Lovina Soenmi Tata Letak dan Disain Henry Adrian Foto Cover Depan nobodycorp.org Foto Cover Belakang Eben Kirksey Karma, Filep Seakan Kitorang Setengah Binatang Rasialisme Indonesia di Tanah Papua Deiyai, Jayapura, 2014 xvi + 137 hlm; 14,5 x 21,5 cm ISBN 978-602-17071-4-2 vi DAFTAR ISI ix Pengantar: Perjuangan Seorang Pegawai Negeri di Papua oleh Jim Elmslie 1 Masa Kecil di Wamena dan Jayapura 13 Biak Berdarah 25 Nasionalisme Papua 45 Perjalanan dalam Gambar 65 Dari Penjara ke Penjara 81 Kritik Langkah Perjuangan 101 Lampiran: Keputusan UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention oleh Freedom Now 129 Epilog: Menemui Filep Karma oleh Anugerah Perkasa vii viii PENGANTAR ix SEAKAN KITORANG SETENGAH BINATANG Perjuangan Seorang Pegawai Negeri di Papua FILEP KARMA, kelahiran 1959, menjalani hidupnya dalam bayang- bayang militer Indonesia. -

Ending Repression in Irian Jaya

INDONESIA: ENDING REPRESSION IN IRIAN JAYA 20 September 2001 ICG Asia Report No 23 Jakarta/Brussels PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/eca9cf/ TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS:.................................................................... ii I. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................1 II. PAPUAN NATIONALISM................................................................................................3 III. INDONESIAN SETTLER COMMUNITIES ..................................................................5 IV. THE PAPUAN ELITE .......................................................................................................9 V. REFORMASI AND THE PAPUAN RENAISSANCE .................................................10 VI. THE PAPUAN PRESIDIUM COUNCIL ......................................................................12 VII. INTERNATIONAL LOBBYING ...................................................................................16 VIII. INDONESIAN GOVERNMENT POLICY ...................................................................17 IX. A SHOW OF FORCE ......................................................................................................20 X. RETURN OF REPRESSION ..........................................................................................21 XI. SPECIAL AUTONOMY..................................................................................................22 XII. CONCLUSION ................................................................................................................ -

Kareba Palu Koro News on Central Sulawesi Emergency Response

december 2018 - II issue #4 KAREBA PALU KORO NEWS ON CENTRAL SULAWESI EMERGENCY RESPONSE The impact of flash flood (11/12) in Salua. Photo: Titik Susana Ristiawaty/ERCB FLASH FLOOD IN SALUA, BATHING WASHING AND LATRINE FACILITIES WERE SWEPT AWAY On Tuesday 11 December evening, again flash flood struck and more,” said Dewi. Salua Village, Kulawi Sub-District, Sigi District, especially in RT “With this current situation, where should we stay now?” Dewi (neighborhood cluster) 1 and RT 2 which are located in Hamlet 3 continued talking and wiping her tears while looking at her (Note: a hamlet is divided into several RWs and one RW consists ruined house. of several RTs.) The event occurred at 7.30 p.m. local time when There are 79 households impacted by the flash flood. The 79 the community were praying in a local mosque and they were houses are damaged and 40 among them are seriously damaged shocked by the sound of roaring water. and could not be inhabited. The height of the muddy water is as “When I was praying last night, suddenly I heard a women high as the knee of an adult. Small bars of wood are mixing with crying and screaming, saying that the water had reached the mud and the flood water. community settlement,” said Jusman Lahudo (59), a Salua Village “Up to now (12 p.m. local time) the water is still flowing in Salua community member. According to him, the flash flood was Village and some heavy equipment are trying to clean up the the hugest and the worst one ever since 1992. -

On the Limits of Indonesia

CHAPTER ONE On the Limits of Indonesia ON July 2, 1998, a little over a month after the resignation of Indonesia’s President Suharto, two young men climbed to the top of a water tower in the heart of Biak City and raised the Morning Star flag. Along with similar flags flown in municipalities throughout the Indonesian province of Irian Jaya, the flag raised in the capital of Biak-Numfor signaled a demand for the political independence of West Papua, an imagined nation comprising the western half of New Guinea, a resource-rich territory just short of Indonesia’s east- ernmost frontier. During the thirty-two years that Suharto held office, ruling through a combination of patronage, terror, and manufactured consent, the military had little patience for such demonstrations. The flags raised by Pap- uan separatists never flew for long; they were lowered by soldiers who shot “security disrupters” on sight.1 Undertaken at the dawn of Indonesia’s new era reformasi (era of reform), the Biak flag raising lasted for four days. By noon of the first day, a large crowd of supporters had gathered under the water tower, where they listened to speeches and prayers, and sang and danced to Papuan nationalist songs. By afternoon, their numbers had grown to the point where they were able to repulse an attack by the regency police, who stormed the site in an effort to take down the flag. Over the next three days, the protesters managed to seal off a dozen square blocks of the city, creating a small zone of West Papuan sovereignty adjoining the regency’s main market and port.