PARLI&Fteht of the COMKONWEALTH of AUSTRALIA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Known Impacts of Tropical Cyclones, East Coast, 1858 – 2008 by Mr Jeff Callaghan Retired Senior Severe Weather Forecaster, Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane

ARCHIVE: Known Impacts of Tropical Cyclones, East Coast, 1858 – 2008 By Mr Jeff Callaghan Retired Senior Severe Weather Forecaster, Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane The date of the cyclone refers to the day of landfall or the day of the major impact if it is not a cyclone making landfall from the Coral Sea. The first number after the date is the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) for that month followed by the three month running mean of the SOI centred on that month. This is followed by information on the equatorial eastern Pacific sea surface temperatures where: W means a warm episode i.e. sea surface temperature (SST) was above normal; C means a cool episode and Av means average SST Date Impact January 1858 From the Sydney Morning Herald 26/2/1866: an article featuring a cruise inside the Barrier Reef describes an expedition’s stay at Green Island near Cairns. “The wind throughout our stay was principally from the south-east, but in January we had two or three hard blows from the N to NW with rain; one gale uprooted some of the trees and wrung the heads off others. The sea also rose one night very high, nearly covering the island, leaving but a small spot of about twenty feet square free of water.” Middle to late Feb A tropical cyclone (TC) brought damaging winds and seas to region between Rockhampton and 1863 Hervey Bay. Houses unroofed in several centres with many trees blown down. Ketch driven onto rocks near Rockhampton. Severe erosion along shores of Hervey Bay with 10 metres lost to sea along a 32 km stretch of the coast. -

MOONBI Is the Newsletter of Fraser Island Defenders Organization Limited

MOONBI is the newsletter of Fraser Island Defenders Organization Limited. The word Moonbi is the Butchulla name of the central part of their homeland, K’gari. FIDO, “The Watchdog of Fraser Island", aims to ensure the wisest use of Fraser Island’s natural resources A warm welcome to all you new FIDO members and, to long-standing FIDO members, thank you for your loyalty and patience. It’s been a long time since the last IN THIS ISSUE: MOONBI was published, in The importance of MOONBI ........ Page 2 November 2018 , shortly before Tribute to John Sinclair AO .......... Page 2 the passing of FIDO’s founder, Reflections from the President .... Page 3 Memorial Lecture 2020 ............... Page 5 inspiration and driving force, John Be like John – Write! .................... Page 7 Sinclair. This issue of MOONBI is FINIA............................................. Page 11 FIDO Executive ............................. Page 12 especially dedicated to the John Sinclair - The early days ....... Page 13 memory of John and his New Members ............................. Page 15 Vale Lew Wyvill QC ...................... Page 16 remarkable life, and also to the FIDO Weedbusters ....................... Page 17 continuing commitment of FIDO to K’gari dingo research ................... Page 18 Don and Lesley Bradley................ Page 20 celebrate and protect the many Memories of John Sinclair ........... Page 21 John Sinclair’s Henchman ............ Page 22 World Heritage values of K’gari. Access K’gari during COVID.......... Page 24 FIDO's Registered -

Rodondo Island

BIODIVERSITY & OIL SPILL RESPONSE SURVEY January 2015 NATURE CONSERVATION REPORT SERIES 15/04 RODONDO ISLAND BASS STRAIT NATURAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE DIVISION DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES, PARKS, WATER AND ENVIRONMENT RODONDO ISLAND – Oil Spill & Biodiversity Survey, January 2015 RODONDO ISLAND BASS STRAIT Biodiversity & Oil Spill Response Survey, January 2015 NATURE CONSERVATION REPORT SERIES 15/04 Natural and Cultural Heritage Division, DPIPWE, Tasmania. © Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment ISBN: 978-1-74380-006-5 (Electronic publication only) ISSN: 1838-7403 Cite as: Carlyon, K., Visoiu, M., Hawkins, C., Richards, K. and Alderman, R. (2015) Rodondo Island, Bass Strait: Biodiversity & Oil Spill Response Survey, January 2015. Natural and Cultural Heritage Division, DPIPWE, Hobart. Nature Conservation Report Series 15/04. Main cover photo: Micah Visoiu Inside cover: Clare Hawkins Unless otherwise credited, the copyright of all images remains with the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgement of the source and no commercial use or sale. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Branch Manager, Wildlife Management Branch, DPIPWE. Page | 2 RODONDO ISLAND – Oil Spill & Biodiversity Survey, January 2015 SUMMARY Rodondo Island was surveyed in January 2015 by staff from the Natural and Cultural Heritage Division of the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (DPIPWE) to evaluate potential response and mitigation options should an oil spill occur in the region that had the potential to impact on the island’s natural values. Spatial information relevant to species that may be vulnerable in the event of an oil spill in the area has been added to the Australian Maritime Safety Authority’s Oil Spill Response Atlas and all species records added to the DPIPWE Natural Values Atlas. -

Steenstrupia ZOOLOGICAL MUSEUM UNIVERSITY of COPENHAGEN

Steenstrupia ZOOLOGICAL MUSEUM UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN Volume 2: 49-90 No. 5: January 25, 1972 Brachyura collected by Danish expeditions in south-eastern Australia (Crustacea, Decapoda) by D. J. G. Griffin The Australian Museum, Sydney Abstract. A total of 73 species of crabs are recorded mainly from localities ranging from the southern part of the Coral Sea (Queensland) through New South Wales and Victoria to the eastern part of the Great Australian Bight (South Australia). Four species are new to the Australian fauna, viz. Ebalia (E.) longimana Ortmann, Oreophorus (O.) ornatus Ihle, Aepiniis indicus (Alcock) and Medaeus planifrons Sakai. Ebalia (Phlyxia) spinifera Miers, Stat.now is raised to rank of species; Philyra undecimspinosa (Kinahan), comb.nov. includes P. miinayeitsis Rathbun, syn.nov. and Eumedonits villosus Rathbun is a syn.nov. of E. cras- simatuis Haswell, comb.nov. Lectotypes are designated for Piiggetia mosaica Whitelegge, PiluDvuis australis Whitelegge and P. moniUfer Haswell. Notes on morphology, taxonomy and general distribution are included. From 1909 to 1914 the eastern and southern parts of the Australian continental shelf and slope were trawled by the Fisheries Investigation Ship "Endeavour". Dr. Th. Mortensen, during his Pacific Expedition of 1914-16, collected speci mens from the decks of the ship as it was working along southern New South Wales during the last year of this survey and visited several other localities along the coasts of New South Wales and Victoria. The Crustacea Brachyura collected by the "Endeavour" were reported on by Rathbun (1918a, 1923) and by Stephenson & Rees (1968b). Rathbun's reports, dealing with a total of 88 species (including 23 new species), still provide a very important source of information on eastern and southern Australian crabs, the only other major report dealing with the crabs of this area being Whitelegge's (1900) account of the collections taken by the "Thetis" along the New South Wales coast in the late 1800's. -

History 1890 – 1966

A HISTORY OF GLOUCESTER HARBOUR TRUSTEES By W. A. Stone Clerk to the Trustees 1958 -1966 PART 1 1890 - 1966 CONTENTS Chapter Page 1 Origin, Constitution and Membership, with details of Navigational Aids erected prior to the incorporation of the Gloucester Harbour Trustees on 5 July 1890 3 2 Navigational Aids 20 3 Finances 39 4 Spanning the Severn Estuary 51 5 New Works and other installation in the Severn Estuary 56 6 Stranding of Vessels and other Incidents 61 7 Northwick Moorings 71 8 Officers and Staff 74 1 FOREWORD In compiling this History I have endeavoured to give the reasons for the appointment of a body of Trustees to control a defined area of the Severn Estuary, and to tell of the great amount of work undertaken by the Trustees and the small staff in administering the requirements of the 1890 Act. It is probable that I have given emphasis to the erection and upkeep of the Navigational Aids, but it must be realised that this was the main requirement of the Act, to ensure that the Trustees, as a Harbour authority, disposed of their income in a manner which was calculated to benefit the navigation of the Severn Estuary. A great deal of research has been necessary and the advice and assistance given to me by the present Officers, and by others who held similar posts in the past, is greatly appreciated. Without their help the task would have been much more formidable. W A Stone Clerk to the Trustees December 1966 2 Chapter One ORIGIN, CONSTITUTION AND MEMBERSHIP WITH DETAILS OF NAVIGATIONAL AIDS ERECTED PRIOR TO THE INCORPORATION OF THE GLOUCESTER HARBOUR TRUSTEES ON 5 JULY 1890 To obtain the reasons for the constitution of a body of Trustees to control a defined area of the River Severn, it is necessary to go back to the year 1861. -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

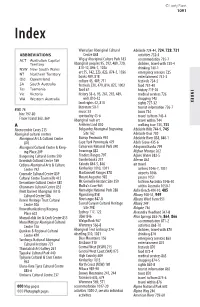

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 311 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feed- back goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. particularly Mark, Cath, Fred, Lucy and the kids OUR READERS in Hobart, and Helen in Launceston. Special Many thanks to the travellers who used thanks as always to Meg, my road-trippin’ the last edition and wrote to us with help- sweetheart, and our daughters Ione and Remy ful hints, useful advice and interesting who provided countless laughs, unscheduled anecdotes: pit-stops and ground-level perspectives along Brian Rieusset, David Thames, Garry the way. Greenwood, Jan Lehmann, Janice Blakebrough, Jon & Linley Dodd, Kevin Callaghan, Lisa Meg Worby Walker, Megan McKay, Melanie Tait, Owen A big thank you to Tasmin, once again. -

THE TASMANIAN HERITAGE FESTIVAL COMMUNITY MILESTONES 1 MAY - 31 MAY 2013 National Trust Heritage Festival 2013 Community Milestones

the NatioNal trust presents THE TASMANIAN HERITAGE FESTIVAL COMMUNITY MILESTONES 1 MAY - 31 MAY 2013 national trust heritage Festival 2013 COMMUNITY MILESTONES message From the miNister message From tourism tasmaNia the month-long tasmanian heritage Festival is here again. a full program provides tasmanians and visitors with an opportunity to the tasmanian heritage Festival, throughout may 2013, is sure to be another successful event for thet asmanian Branch of the National participate and to learn more about our fantastic heritage. trust, showcasing a rich tapestry of heritage experiences all around the island. The Tasmanian Heritage Festival has been running for Thanks must go to the National Trust for sustaining the momentum, rising It is important to ‘shine the spotlight’ on heritage and cultural experiences, For visitors, the many different aspects of Tasmania’s heritage provide the over 25 years. Our festival was the first heritage festival to the challenge, and providing us with another full program. Organising a not only for our local communities but also for visitors to Tasmania. stories, settings and memories they will take back, building an appreciation in Australia, with other states and territories following festival of this size is no small task. of Tasmania’s special qualities and place in history. Tasmania’s lead. The month of May is an opportunity to experience and celebrate many Thanks must also go to the wonderful volunteers and all those in the aspects of Tasmania’s heritage. Contemporary life and visitor experiences As a newcomer to the State I’ve quickly gained an appreciation of Tasmania’s The Heritage Festival is coordinated by the National heritage sector who share their piece of Tasmania’s historic heritage with of Tasmania are very much shaped by the island’s many-layered history. -

Newsletter 16 Xmas 2016

FRIENDSFRIENDS OFOF TASMAN ISLAND NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER No. 1416 December,MAY, 2015 2016 Written & Compiled by Erika Shankley November has been a busy month for FoTI - read AWBF 2017 all about it in the following pages! FoTI, FoMI & FoDI will have a presence at next year’s Australian 2 Light between Oceans Wooden Boat Festival: 10—13 3 Tasman Landing February 2017. Keep these dates 4 24th Working bee free—more details as they come to 6 Tasmanian Lighthouse Conference hand. Carol’s story 8 Karl’s story SEE US ON THE WILDCARE WEB SITE 9 Pennicott Iron Pot cruise http://wildcaretas.org.au/ 10 Custodians of lighthouse paraphernalia Check out the latest news on the 11 Merchandise for sale Home page or click on Branches to 12 Parting Shot see FoTI’s Tasman Island web page. We wish everyone a happy and safe holiday FACEBOOK season and look forward to a productive year on A fantastic collection of anecdotes, Tasman Island in 2017. historical and up-to-date information and photos about Tasman and other lighthouses around the world. Have you got something to contribute, add Erika a comment or just click to like us! FoTI shares with David & Trauti Reynolds & their son Mark, much sadness in the death of their son Gavin after a long illness. Gavin’s memory is perpetuated in the design of FoTI’s logo. FILM: Light between Oceans Page 2 Early in November a few FoTI supporters joined members of the public at the State Cinema for the Hobart launch of the film Light between Oceans, a dramatisation of the book of the same name by ML Steadman. -

The Story of Our Lighthouses and Lightships

E-STORy-OF-OUR HTHOUSES'i AMLIGHTSHIPS BY. W DAMS BH THE STORY OF OUR LIGHTHOUSES LIGHTSHIPS Descriptive and Historical W. II. DAVENPORT ADAMS THOMAS NELSON AND SONS London, Edinburgh, and Nnv York I/K Contents. I. LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY, ... ... ... ... 9 II. LIGHTHOUSE ADMINISTRATION, ... ... ... ... 31 III. GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OP LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... 39 IV. THE ILLUMINATING APPARATUS OF LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... 46 V. LIGHTHOUSES OF ENGLAND AND SCOTLAND DESCRIBED, ... 73 VI. LIGHTHOUSES OF IRELAND DESCRIBED, ... ... ... 255 VII. SOME FRENCH LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... ... ... 288 VIII. LIGHTHOUSES OF THE UNITED STATES, ... ... ... 309 IX. LIGHTHOUSES IN OUR COLONIES AND DEPENDENCIES, ... 319 X. FLOATING LIGHTS, OR LIGHTSHIPS, ... ... ... 339 XI. LANDMARKS, BEACONS, BUOYS, AND FOG-SIGNALS, ... 355 XII. LIFE IN THE LIGHTHOUSE, ... ... ... 374 LIGHTHOUSES. CHAPTER I. LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY. T)OPULARLY, the lighthouse seems to be looked A upon as a modern invention, and if we con- sider it in its present form, completeness, and efficiency, we shall be justified in limiting its history to the last centuries but as soon as men to down two ; began go to the sea in ships, they must also have begun to ex- perience the need of beacons to guide them into secure channels, and warn them from hidden dangers, and the pressure of this need would be stronger in the night even than in the day. So soon as a want is man's invention hastens to it and strongly felt, supply ; we may be sure, therefore, that in the very earliest ages of civilization lights of some kind or other were introduced for the benefit of the mariner. It may very well be that these, at first, would be nothing more than fires kindled on wave-washed promontories, 10 LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY. -

QUEENSLAND—HARBOURS, RIVERS and MARINE [By the President, NORMAN S

PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS QUEENSLAND—HARBOURS, RIVERS AND MARINE [By the President, NORMAN S. PIXLEY, C.M.G., M.B.E., V.R.D., Kt.O.N., F.R.Hist.S.Q.] (Read at the Annual Meeting of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, 28 September 1972) The growth and development of ports to handle seaborne trade has been vital to Australia, but nowhere has this been so marked as in Queensland, fortunate in possessing more deep-sea ports than any other State. From the founding of the convict settlement in Moreton Bay in 1824 and for many years thereafter, settlement, development and supplies depended entirely on sea com munications. With the movement of explorers, prospectors and settlers steadily northward, vessels sailed up the coast carrying supplies for the overland travellers: some prospectors and others took passage by sea rather than face the land journey. Both passengers and cargo had to be put ashore safely at a point on the coast nearest to their destination with sheltered water. In the earlier days of the nineteenth century it was essential that some of the vessels find shelter where there were supplies of water, firewood for the ship's galley, with such food as the virgin countryside offered and where the mariner in distress could make good repairs to his ship. With great thankfulness James Cook found such a haven in the Endeavour River in time of desperate need in 1770. As settlements grew and developed, merchant ships, in addition to maintaining services on the coast, now carried our products to oversea markets, returning with migrants and goods. -

3966 Tour Op 4Col

The Tasmanian Advantage natural and cultural features of Tasmania a resource manual aimed at developing knowledge and interpretive skills specific to Tasmania Contents 1 INTRODUCTION The aim of the manual Notesheets & how to use them Interpretation tips & useful references Minimal impact tourism 2 TASMANIA IN BRIEF Location Size Climate Population National parks Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area (WHA) Marine reserves Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) 4 INTERPRETATION AND TIPS Background What is interpretation? What is the aim of your operation? Principles of interpretation Planning to interpret Conducting your tour Research your content Manage the potential risks Evaluate your tour Commercial operators information 5 NATURAL ADVANTAGE Antarctic connection Geodiversity Marine environment Plant communities Threatened fauna species Mammals Birds Reptiles Freshwater fishes Invertebrates Fire Threats 6 HERITAGE Tasmanian Aboriginal heritage European history Convicts Whaling Pining Mining Coastal fishing Inland fishing History of the parks service History of forestry History of hydro electric power Gordon below Franklin dam controversy 6 WHAT AND WHERE: EAST & NORTHEAST National parks Reserved areas Great short walks Tasmanian trail Snippets of history What’s in a name? 7 WHAT AND WHERE: SOUTH & CENTRAL PLATEAU 8 WHAT AND WHERE: WEST & NORTHWEST 9 REFERENCES Useful references List of notesheets 10 NOTESHEETS: FAUNA Wildlife, Living with wildlife, Caring for nature, Threatened species, Threats 11 NOTESHEETS: PARKS & PLACES Parks & places,