The History and Development of the Percussion Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Annotated Bibliography of Current Research in the Field of the Medical Problems of Trumpet Playing

AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF CURRENT RESEARCH IN THE FIELD OF THE MEDICAL PROBLEMS OF TRUMPET PLAYING D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School at The Ohio State University By Mark Alan Wade, B.M., M.M. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Document Committee: Professor Timothy Leasure, Adviser Approved by Professor Alan Green Dr. Russel Mikkelson ________________________ Adviser Graduate Program in Music ABSTRACT The very nature of the lifestyle of professional trumpet players is conducive to the occasional medical problem. The life-hours of diligent practice and performance that make a performer capable of musical expression on the trumpet also can cause a host of overuse and repetitive stress ailments. Other medical problems can arise through no fault of the performer or lack of technique, such as the brain disease Task-Specific Focal Dystonia. Ailments like these fall into several large categories and have been individually researched by medical professionals. Articles concerning this narrow field of research are typically published in their respective medical journals, such as the Journal of Applied Physiology . Articles whose research is pertinent to trumpet or horn, the most similar brass instruments with regard to pitch range, resistance and the intrathoracic pressures generated, are often then presented in the instruments’ respective journals, ITG Journal and The Horn Call. Most articles about the medical problems affecting trumpet players are not published in scholarly music journals such as these, rather, are found in health science publications. Herein lies the problem for both musician and doctor; the wealth of new information is not effectively available for dissemination across fields. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Jeff Snyder.WITOLD\My Documents

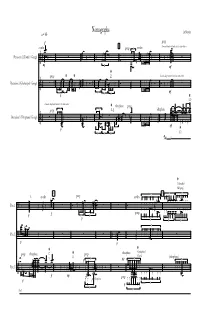

Nomographs q = 66 Jeff Snyder gongs 5 crotalesf gongs crotales diamond-shaped noteheads indicate rattan beaters 5 Percussion 1 (Crotales / Gongs) 5 P F D diamond-shaped noteheads indicate rattan beaters gongs _ Percussion 2 (Glockenspiel / Gongs) 3 3 5 5 5 F p G diamond-shaped noteheads indicate rattan beaters 5 vibraphone gongs gongs 3 D, A_ vibraphone Percussion 3 (Vibraphone / Gongs) 5 F p 5 5 5 E A (crotales) A# (gong) 10 7 15 7 7 l.v. crotales gongs crotales Perc.1 gongs 5 5 f p p 7 7 7 7 Perc.2 p p A (vibraphone) gongs vibraphone C gongs vibraphone G E (gong) (vibraphone) 5 7 7 p pp Perc.3 gongs f P vibraphone p 7 p 5 (Ped.) p 7 2 (rattan on both side (damp all) A (crotales) 20 5 5 3 and center of gong) gongs 3 Perc.1 3 3 f (rattan on both side (l.v.) C# and center of gong) 3 3 3 3 3 3 Perc.2 vibraphone D (vibraphone) F vibraphone (damp all) 3 D# (gong) gong vibraphone C# gongs (vibraphone) Perc.3 3 3 5 5 gongs 3 5 25 crotales 5 30 B (rattan on side) (all) gongs 3 Perc.1 5 (rattan on both side 5 5 gongs 5 p 5 5 5 f (rattan on side) and center of gong) (all) -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 29-Apr-2010 I, Tyler B Walker , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Composition It is entitled: An Exhibition on Cheerful Privacies Student Signature: Tyler B Walker This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Mara Helmuth, DMA Mara Helmuth, DMA Joel Hoffman, DMA Joel Hoffman, DMA Mike Fiday, PhD Mike Fiday, PhD 5/26/2010 587 An Exhibition On Cheerful Privacies Three Landscapes for Tape and Live Performers Including Mezzo-Soprano, Bb Clarinet, and Percussion A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2010 by Tyler Bradley Walker M.M. Georgia State University January 2004 Committee Chair: Mara Helmuth, DMA Abstract This document consists of three-musical landscapes totaling seventeen minutes in length. The music is written for a combination of mezzo-soprano, Bb clarinet, percussion and tape. One distinguishing characteristic of this music, apart from an improvisational quality, involves habituating the listener through consistent dynamics; the result is a timbrally-diverse droning. Overall, pops, clicks, drones, and resonances converge into a direct channel of aural noise. One of the most unique characteristics of visual art is the strong link between process and esthetic outcome. The variety of ways to implement a result is astounding. The musical landscapes in this document are the result of an interest in varying my processes; particularly, moving mostly away from pen and manuscript to the sequencer. -

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Panther Auto Corner Left: the Band Marches on to Victory

PA NTHER PRIDE Volume 11, I ssue #2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Band's Victory in M aryville Page 1: Bands Victory in Maryville The marching band has had a fantastic Middle School Sports season! At the first competition in Carrollton they Middle School Football had a high music score but a low marching score and Page 2: Clubs and Activities flipped the scores in Cameron. On October 26th they Art Club had a competition in Maryville where they placed Elementary News second in their class 2A, only four points away from Blast Off Into the School Year first. The band had the third-highest music score over all the bands that performed. The band was very Stacking It Up excited to beat some very good bands for their last Books for First Grade marching competition of the year and are getting Character Assembly ready for concert season. Page 3: Current Events Florida Man Drumline this year had a good season. They Hong Kong Protests only had two competitions compared to the three that Creative Minds the whole band had. They played Blazed Blues and Lobster Walk for their performance. The drumline Photography Basics placed fourth in Carrollton and didn?t place in Kara Claypole, Mr.Dunker, and Ysee Chorot celebrate their "Song of the Sea" Cameron. second place trophy as they marched at Maryville for the "Bernard's Poem" Northwest Homecoming Parade. Page 4: Panther Auto Corner Left: The band marches on to victory. Ask Anonymous Entertainment Corbin's Destroy... Page 5: Joker Is a Marvel New Music Releases Page 6: New Video Game Releases Page 7: Horoscopes Page 8: November Menu Polo M iddle School Sports M iddle School Football Stats Board - By: M r. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

The PAS Educators' Companion

The PAS Educators’ Companion A Helpful Resource of the PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY EDUCATION COMMITTEE Volume VIII Fall 2020 PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY 1 EDUCATORS’ COMPANION THE PAS EDUCATORS’ COMPANION PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY EDUCATION COMMITTEE ARTICLE AUTHORS DAVE GERHART YAMAHA CORPORATION OF AMERICA ERIK FORST MESSIAH UNIVERSITY JOSHUA KNIGHT MISSOURI WESTERN STATE UNIVERSITY MATHEW BLACK CARMEL HIGH SCHOOL MATT MOORE V.R. EATON HIGH SCHOOL MICHAEL HUESTIS PROSPER HIGH SCHOOL SCOTT BROWN DICKERSON MIDDLE SCHOOL AND WALTON HIGH SCHOOL STEVE GRAVES LEXINGTON JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL JESSICA WILLIAMS ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY EMILY TANNERT PATTERSON CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS How to reach the Percussive Arts Society: VOICE 317.974.4488 FAX 317.974.4499 E-MAIL [email protected] WEB www.pas.org HOURS Monday–Friday, 9 A.M.–5 P.M. EST PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS BUILDING A STRONG FOUNDATION OF THE SNARE DRUM FULCRUM 3 by Dr. Dave Gerhart CONSISTENCY MATTERS: Developing a Shared Vernacular for Beginning 6 Percussion and Wind Students in a Heterogeneous Classroom by Dr. Erik M. Forst PERFECT PART ASSIGNMENTS - ACHIEVING THE IMPOSSIBLE 10 by Dr. Joshua J. Knight TOOLS TO KEEP STUDENTS INTRIGUED AND MOTIVATED WHILE PRACTICING 15 FUNDAMENTAL CONCEPTS by Matthew Black BEGINNER MALLET READING: DEVELOPING A CURRICULUM THAT COVERS 17 THE BASES by Matt Moore ACCESSORIES 26 by Michael Huestis ISOLATING SKILL SETS, TECHNIQUES, AND CONCEPTS WITH 30 BEGINNING PERCUSSION by Scott Brown INCORPORATING PERCUSSION FUNDAMENTALS IN FULL BAND REHEARSAL 33 by Steve Graves YOUR YOUNG PERCUSSIONISTS CRAVE ATTENTION: Advice and Tips on 39 Instructing Young Percussionists by Jessica Williams TEN TIPS FOR FABULOUS SNARE DRUM FUNDAMENTALS 46 by Emily Tannert Patterson ADDITIONAL RESOURCES 49 2 PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY EDUCATORS’ COMPANION BUILDING A STRONG FOUNDATION OF THE SNARE DRUM FULCRUM by Dr. -

Percussion Ensemble Spring Concert

Kennesaw State University THE GSO College of the Arts APPLAUDS THE School of Music KSU SCHOOL OF MUSIC! presents Thank you for fostering the future of our students Percussion Ensemble and their heritage of Spring Concert the arts. John Lawless, director Photo: Tom Kells Photo: Tom Call us at 770-429-7016 Visit us at georgiasymphony.org Monday, April 28, 2014 8:00 p.m. Audrey B. and Jack E. Morgan, Sr. Concert Hall Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center One Hundred Twenty-seventh Concert of the 2013-14 Concert Season CopelandsKSU_0713_CopelandsKSU_0713 7/5/13 Program LYNN GLASSOCK (b.1946) Street Talk Famous New Orleans Style Food and USDA JOHN PSATHAS (b.1966) PRIME One Summary Erik Kosman, marimba solo BOB BECKER (b.1947) Prisoners of the Image Factory Selena Sanchez Featuring New Orleans Live Jazz Natasha Black Sunday Brunch Music PM AM to 3 Served from Levi Lyman From 11 Buffet 10 AM to 3 PM KENNESAW•770-919-9612 1142 Ernest W.Barrett Pkwy.,NW LORENZO SANFORD (b.1962) www.CopelandsAtlanta.com A Leap Of Faith JOHN CAGE (1912-1992) Credo In US Erik Kosman Cameron Austin Janna Graham Judy Cole, piano ROBERT MARINO (unknown) Eight on 3 and Nine on 2 Levi Lyman Kyle Pridgen Uncle Maddio’s Pizza Joint BLAKE TYSON (unknown) 745 Chastain Road Not Far From Here Next to Starbucks & Firehouse Subs 770-573-1694 Percussion Ensemble Personnel Cameron Austin Levi Lyman Natasha Black Kyle Pridgen Janna Graham Selena Sanchez Sydney Hunter Jada Taylor Erik Kosman Program Notes Street Talk LYNN GLASSOCK (b.1946) Lyn Glassock is one of the most prolific composers for the percussion ensemble living today. -

What Do Your Dreams Sound Like?

Volume 6 › 2017 Orchestral, Concert & Marching Edition What do your Dreams sound like? PROBLEM SOLVED WHY DREAM? D R E A M 2 0 1 7 1 D R E A M 2 0 1 7 Attention Band Directors, Music Teachers, “The Cory Band have been the World's No.1 brass band for the past decade. We feel privileged Orchestra Conductors! to have been associated with We understand how frustrating it can be to try to find the professional Dream Cymbals since 2014. quality, exceptionally musical sounds that you need at a price that fits into From the recording studio to your budget. Everyone at Dream is a working musician so we understand the challenges from our personal experiences. You should not have to Rick Kvistad of the concert halls across the UK and sacrifice your sound quality because of a limited budget. San Francisco Opera says: abroad, we have come to rely From trading in your old broken cymbals through our recycling program, on the Dream sound week in putting together custom tuned gong sets, or creating a specific cymbal set “I love my Dream Cymbals up that we know will work with your ensemble, we love the challenge of week out.” creating custom solutions. for both the orchestra and Visit dreamcymbals.com/problemsolved and get your personal cymbal assistant. By bringing together our network of exceptional dealers and our my drum set. Dr. Brian Grasier, Adjunct Instructor, Percussion, in-house customer service team, we can provide a custom solution tailored They have a unique Sam Houston State University says: to your needs, for free. -

To Read Raidernet Daily

RaiderNet Daily G. Ray Bodley High School, Fulton, NY Volume 2, Number 24 Monday, October 25, 2010 Raiders set for sectional opener By Colin Shannon goals. This gives the keeper an 81.3 save per- tough battle. The second round playoff game centage on the season, a good mark to be at. will take place Thursday night at 6 P.M. The Fulton varsity boys soccer team earned a The Cortland Tigers are led by a select few The Raider girls varsity will also open sec- playoff birth as the tenth seed after finishing on their roster. The two main offensive threats tional play on Tuesday, travelling to Indian the season with a record of 8-7-1. Unfortu- are Colby Reagan, with 5 goals and 3 assits, River for a 6 p.m. clash. Fulton, at 7-9, is the nately, having such a low rank forces the boys and Patrick Mahar with 5 goals and two as- #9 seed while the 7-7-1 Warriors are seeded to play a road game at Cortland to advance to sists. Once one looks past these two, the third just ahead of them at #8. Tuesday’s winner will the next round. The Cortland Tigers possess a scorer is Gregory Masler with 3 goals and a have a formidable task ahead as they must face record of 8-6-2, with one additional tie being lone assist. #1 seeded Jamesville-Dewitt at a time and the difference between the tenth and the sev- Standing between the pipes is keeper Chad place to be determined. -

KASHCHEI for Nine Instruments and Electronics

KASHCHEI For Nine Instruments and Electronics Nina C. Young November 2010 KASHCHEI for nine instruments and electronics November 2010 Approximate duration: 18:00 Premiered February 8, 2011, Live@CIRMMT – Montreal, Canada Instrumentation: Program Notes: flute (+ piccolo) Kashchei, for nine instruments and electronics, was written by Nina C. Young in 2010 in partial fulfillment of the Master’s of Music degree at McGill University under the supervision of Prof. Sean clarinet in B (+ bass clarinet) b Ferguson. The piece is a representation of Kashchei – a character from Russian folklore who makes an trumpet in C (+ piccolo trumpet; straight and harmon mutes) appearance in many popular fairytales or skazki. H is a dark, evil person of ugly, senile appearance who principally menaces young women. Kashchei cannot be killed by conventional means targeting his body. 2 percussion: Rather, the essence of his life is hidden outside of his flesh in a needle within an egg. Only by finding this I – vibraphone egg and breaking the needle can one overcome Kashchei’s powers. In one skazka, the princess Tsarevna’s I – almglocken (F4, G#4, A4, C5, D#5, E5, F5, G5, A5, B5, C#6) Darissa asks Kashchei where his death lies. Infatuated by her beauty, he let’s down his guard and I – crotales (E5, F5) eventually explains, “My death is far from hence, and hard to find, on the ocean wide: in that sea is the island of I – triangle I – wind chime Buyan, and upon this island there grows a green oak, and beneath this oak is an iron chest, and in this chest is a small I – splash cymbal basket, and in this basket is a hare, and in this hare is a duck, and in this duck is an egg; and he who finds this egg and I – suspended cymbal (medium) breaks it, at the same instant causes my death.” My own piece explores the seven layers and death of Kashchei. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums.