No Trust at the NFL: League's Network Passes Rule of Reason Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 Nfl Tv Plans, Announcers, Programming

NFL KICKS OFF WITH NATIONAL TV THURSDAY NIGHT GAME; NFL TV 2004 THE NFL is the only sports league that televises all regular-season and postseason games on free, over-the-air network television. This year, the league will kick off its 85th season with a national television Thursday night game in a rematch of the 2003 AFC Championship Game when the Indianapolis Colts visit the Super Bowl champion New England Patriots on September 9 (ABC, 9:00 PM ET). Following is a guide to the “new look” for the NFL on television in 2004: • GREG GUMBEL will host CBS’ The NFL Today. Also joining the CBS pregame show are former NFL tight end SHANNON SHARPE and reporter BONNIE BERNSTEIN. • JIM NANTZ teams with analyst PHIL SIMMS as CBS’ No. 1 announce team. LESLEY VISSER joins the duo as the lead sideline reporter. • Sideline reporter MICHELE TAFOYA joins game analyst JOHN MADDEN and play-by-play announcer AL MICHAELS on ABC’s NFL Monday Night Football. • FOX’s pregame show, FOX NFL Sunday, will hit the road for up to seven special broadcasts from the sites of some of the biggest games of the season. • JAY GLAZER joins FOX NFL Sunday as the show’s NFL insider. • Joining ESPN is Pro Football Hall of Fame member MIKE DITKA. Ditka will serve as an analyst on a variety of shows, including Monday Night Countdown, NFL Live, SportsCenter and Monday Quarterback. • SAL PAOLANTONIO will host ESPN’s EA Sports NFL Match-Up (formerly Edge NFL Match-Up). NFL ANNOUNCER LINEUP FOR 2004 ABC NFL Monday Night Football: Al Michaels-John Madden-Michele Tafoya (Reporter). -

Verizon Fios Channel Guide

1/14/2020 Extreme HD Print 344 Ch, 151 HD # A 169 A Wealth of Entertainment 669 A Wealth of Entertainment HD 181 A&E 681 A&E HD 571 ACC Network HD 119 AccuWeather DC MD VA 619 AccuWeather DC MD VA HD 424 Action Max 924 Action Max HD 425 Action Max West 231 AMC 731 AMC HD 125 American Heroes Channel 625 American Heroes Channel HD 130 Animal Planet 630 Animal Planet HD 215 AXS tv 569 AXS tv HD # B 765 BabyFirst HD 189 BBC America 689 BBC America HD 107 BBC World News 609 BBC World News HD 596 beIN Sports HD 270 BET 225 BET Gospel 770 BET HD 213 BET Jams 219 BET Soul 330 Big Ten 1 331 Big Ten 2 Programming Service offered in each package are subject to change and not all programming Included Channel Premium Available For Additional Cost services will be available at all times, Blackout restrictions apply. 1/15 1/14/2020 Extreme HD Print 344 Ch, 151 HD 333 Big Ten 3 85 Big Ten Network 585 Big Ten Network HD 258 Boomerang Brambleton Community 42 Access [HOA] 185 Bravo 685 Bravo HD 951 Brazzers 290 BYU Television # C 109 C-SPAN 110 C-SPAN 2 111 C-SPAN 3 599 Cars.TV HD 257 Cartoon Network 757 Cartoon Network HD 94 CBS Sports Network 594 CBS Sports Network HD 277 CGTN 420 Cinemax 920 Cinemax HD 421 Cinemax West 921 Cinemax West HD 236 Cinémoi 221 CMT 721 CMT HD 222 CMT Music 102 CNBC 602 CNBC HD+ 100 CNN 600 CNN HD 105 CNN International 190 Comedy Central 690 Comedy Central HD 695 Comedy.TV HD 163 Cooking Channel 663 Cooking Channel HD Programming Service offered in each package are subject to change and not all programming Included Channel Premium Available For Additional Cost services will be available at all times, Blackout restrictions apply. -

Inside Tv 12-31

The Goodland Daily News / Tuesday, December 31, 2002 7 Kansas going to electronic titles Channel guide Kansans who borrow money to buy system. should rely on their vehicle registration Prime time 2 PBS; 3 TBS; 4 ABC; 5 HBO; 6 CNN; cars, trucks, motorcycles, trailers and “First, financial institutions appre- receipt as their ownership document. 7 CBS; 8 NBC (KS); 11 TVLND; 12 other motor vehicles will not get ciate the added security of paperless “It’s going to be a big adjustment for ESPN; 13 FOX; 15 MAX; 16 TNN; 18 printed paper titles starting Thursday. titles,” she said. “Second, the vehicle some…,” she said. “With a paperless LIFE; 20 USA; 21 SHOW; 22 TMC; 23 If there is a lien on a vehicle, the owners won’t have to keep track of title, the vehicle is still in their name, TV MTV; 24 DISC; 27 VH1; 28 TNT; 30 Kansas Department of Revenue’s Di- their titles and obtain duplicates when but without the expensive title paper FSN; 31 CMT; 32 FAM; 33 NBC (CO); vision of Vehicles will hold the title titles are lost. Finally, the state will be and security features.” 34 NICK; 36 A&E; 38 SCI; 39 TLC; 40 electronically until the loan is paid in able to issue titles more efficiently, The 2002 Legislature authorized FX; 45 FMC; 49 E!; 51 TRAV; 53 WB; full or the vehicle is sold. with fewer data entry errors, improv- electronic liens and titles, she said, 54 ESPN2; 55 ESPN News; 58 HIST; Shelia Walker, director of vehicles, ing quality assurance.”Until the lien is making Kansas the ninth state to go schedule 62 HGTV; 99 WGN. -

Oocketfilecopyoriginal

OOCKET FILE COpy ORIGINAL REDACTED VERSION FILED/ACCEPTED APR 222009 Before the Federal Communlcatioos CommiSSion FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Office olltle Secrelary Washington, DC In the Matter of ) ) MB Docket No. 08-214 NFL Enterprises LLC, ) File No. CSR-7876-P Complainant ) ) ) v. ) ) Com cast Cable Communications, LLC ) Defendant ) DIRECT TESTIMONY OF LARRY GERBRANDT 1. My name is Larry Gerbrandt. I am launder and principal ofMedia Valuation Partners, a consulting services firm that provides valuation, markct research and litigation support to a broad range of public and private enterprises. I havc more than 30 years of experience as a media and entertainment analyst and as a research and publishing executive. 2. Throughout my career, 1have locused on the economic and strategic implications ofthe intersection between traditional media and emerging content delivery technologies. I have experience in film and video production, commercial photography, cable TV system operations, and magazine publishing. 3. In 1984, ljoined Kagan World Media, a grouodbreaking media research organization. As senior analyst and senior vice president of Kagan's entertainment division, I oversaw more than two dozen of its newsletters and databooks and led its valuation practice. 4. In 2000, aHer Kagan's sale to Primedia, I became its ChicfOpcrating Officer and led its integration into Primedia's MediaCentral division. Upon Kagan's subsequent sale to MCG Capilal, I joined AlixPartners to lead its entcrtainmcnt consulting and litigation support practice. 5. In 2005, I was recruited by The Nielsen Company to become Senior Vice President and General Manager ofNielsen Analytics where I focused On emerging media technology economics and conducted primary research on COnSumer adoption of new media platlorms. -

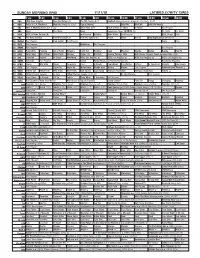

Sunday Morning Grid 11/11/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/11/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Arizona Cardinals at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Eyewitness News 10:00AM (N) Dr. Scott Dr. Scott 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Planet Weird DIY Sci They Fight (2018) (Premiere) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Belton Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Rick Steves’ Europe: Great German Cities (TVG) 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

Nominees for the 29 Annual Sports Emmy® Awards

NOMINEES FOR THE 29 TH ANNUAL SPORTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCE AT IMG WORLD CONGRESS OF SPORTS Winners to be Honored During the April 28 th Ceremony At Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center Frank Chirkinian To Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York, NY – March 13th, 2008 - The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 29 th Annual Sports Emmy ® Awards at the IMG World Congress of Sports at the St. Regis Hotel in Monarch Bay/Dana Point, California. Peter Price, CEO/President of NATAS was joined by Ross Greenberg, President of HBO Sports, Ed Goren President of Fox Sports and David Levy President of Turner Sports in making the announcement. At the 29 th Annual Sports Emmy ® Awards, winners in 30 categories including outstanding live sports special, sports documentary, studio show, play-by-play personality and studio analyst will be honored. The Awards will be given out at the prestigious Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center located in the Time Warner Center on April 28 th , 2008 in New York City. In addition, Frank Chirkinian, referred to by many as the “Father of Televised Golf,” and winner of four Emmy ® Awards, will receive this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award that evening. Chirkinian, who spent his entire career at CBS, was given the task of figuring out how to televise the game of golf back in 1958 when the network decided golf was worth a look. Chirkinian went on to produce 38 consecutive Masters Tournament telecasts, making golf a mainstay in sports broadcasting and creating the standard against which golf telecasts are still measured. -

View 24 Month Offers and Channels Lineups

24-MONTH GENERAL MARKET OFFERS ENTERTAINMENT CHOICETM ULTIMATE PREMIERTM All Included Package All Included Package All Included Package All Included Package Over 160 Channels Over 185 Channels Over 250 Channels Over 330 Channels DIRECTV All Included packages include programing fee, monthly service & equipment fees for one Genie HD DVR, and standard pro installation. ($7 per additional TV/receiver per month). $102.00/mo.: Regular Price $122.00/mo.: Regular Price $151.00/mo.: Regular Price $206.00/mo.: Regular Price – $32.01/mo.: Programming Rebate – $47.01/mo.: Programming Rebate – $61.01/mo.: Programming Rebate – $66.01/mo.: Programming Rebate $ 99 $ 99 $ 99 $ 99 69 MO. + TAX 74 MO. + TAX 89MO. + TAX 139 MO. + TAX FOR 12 MONTHS with 24-month agreement FOR 12 MONTHS with 24-month agreement FOR 12 MONTHS with 24-month agreement FOR 12 MONTHS with 24-month agreement – $5.00/mo.: Autopay & Paperless Bill Credit – $5.00/mo.: Autopay & Paperless Bill Credit – $5.00/mo.: Autopay & Paperless Bill Credit – $5.00/mo.: Autopay & Paperless Bill Credit $ 99 + TAX $ 99 + TAX $ 99 + TAX $ 99 + TAX 64 MO. 69 MO. 84 MO. 134 MO. FOR 12 MONTHS FOR 12 MONTHS FOR 12 MONTHS FOR 12 MONTHS $102/mo in months 13-24 (subject to change). $122/mo in months 13-24 (subject to change). $151/mo in months 13-24 (subject to change). $206/mo in months 13-24 (subject to change). Regional Sports Fee up to $9.99mo. is extra and applies. Premiums Included Get first 3 months of HBO MAX,™ Cinemax®, SHOWTIME®, STARZ®, and EPIX® included at no extra charge. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JULY 21, 2020 NHL ANNOUNCES 2020 STANLEY CUP QUALIFIERS NORTH AMERICAN BROADCAST SCHEDULE Comprehensive Co

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JULY 21, 2020 NHL ANNOUNCES 2020 STANLEY CUP QUALIFIERS NORTH AMERICAN BROADCAST SCHEDULE Comprehensive Coverage of All Stanley Cup Qualifying and Round Robin Games Across NBC Sports, Sportsnet, TVA Sports, NHL Network, NHL.TV and NHL Center Ice NEW YORK (July 21, 2020) – The National Hockey League today announced the national North American broadcast schedule for the 2020 Stanley Cup Qualifiers™, which begin Saturday, Aug. 1, with a slate of five games across NBC, NBCSN, NHL Network™, NHL.TV™ and NHL Center Ice® in the U.S., and Sportsnet, CBC and TVA Sports in Canada. The full North American broadcast schedule – including the 2020 Stanley Cup Qualifiers™ (Qualifying Round and Round Robin) and exhibition games (July 28-30) – is available in its entirety here. Starting times and national broadcast information for games listed as TBD will be announced when available. In the U.S., many games will be available in the local market on the team partner regional sports network. The NHL’s national North American broadcast schedule across NBC Sports, Sportsnet, TVA Sports, NHL Network, NHL.TV and NHL Center Ice includes: NBC Sports (U.S.) • NBC Sports will present up to 120 hours of coverage of the 2020 Stanley Cup Qualifiers™ on NBC, NBCSN and USA Network beginning Aug. 1, highlighted by at least 10 hours of wall-to-wall NHL action each day from Aug. 1-5, comprised of Qualifying Round and Round Robin matchups. • Beginning Saturday, Aug. 1, through Wednesday, Aug. 5, NBC Sports will present coverage from at least four games each day across NBC, NBCSN and USA Network, including some games that will be joined in progress. -

The River Weekly News Will Correct Factual Errors Or Matters of Emphasis and Interpretation That Appear in News Stories

Happy FREE New Year! Take Me Home VOL. 9, NO. 1 From the Beaches to the River District downtown Fort Myers JANUARY 1, 2010 Shell Point Welcomes Tim Zimmerman & The King’s Brass Roseate spoonbills Christmas Bird Count January 2 oin in for the 110th Christmas Bird Count beginning at 7 a.m. Saturday, January 2 at storm water treatment area (STA) 5. STA-5 is located on JBlumberg Road in Hendry County, 12 miles south of the intersection of Tim Zimmerman & The King’s Brass Blumberg and County Road 835. Blumberg Road ends at the gate after 10 miles of asphalt and two miles of dirt. Everglades stormwater treatment areas are renowned he next concert in the 2009-10 Season of Praise Concert Series by The bird-watching havens. Village Church at Shell Point Retirement Community will be Tim Zimmerman Stormwater treatment areas (STAs) are the water-cleaning workhorses of Everglades T& The King’s Brass on January 10. The concert will begin at 6:15 p.m. and restoration. They have also become havens for wildlife and outdoor enthusiasts alike. will be in The Village Church auditorium on The Island at Shell Point. The South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) is joining with the Hendry- “Tim Zimmerman & The King’s Brass have performed at Shell Point as part of this Glades Audubon Society as the group conducts its portion of the 110th Christmas concert series for the past several years,” said Randy Woods, minister of worship and Bird Count in STA-5. This is the Hendry-Glades Audubon’s third year conducting the music for The Village Church. -

Federal Communications Commission FCC 02-287 Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission FCC 02-287 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of: ) ) Implementation of the Satellite Home Viewer ) Improvement Act of 1999: ) CS Docket No. 00-2 ) Application of Network Non-Duplication, ) Syndicated Exclusivity, and Sports Blackout ) Rules To Satellite Retransmissions of Broadcast ) Signals ) ORDER ON RECONSIDERATION Adopted: October 10, 2002 Released: October 17, 2002 By the Commission: TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraph I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 2 II. BACKGROUND AND SUMMARY OF PETITIONS................................................................... 3 III. ORDER ON RECONSIDERATION............................................................................................... 4 A. Transition Phase-In Period.................................................................................................. 4 B. Sports Blackout Rule .......................................................................................................... 6 1. The sports blackout rule applied to retransmission of network stations. ............... 6 2. Forty-eight hour Notification Period ..................................................................... 9 C. Definition of “Local” for Purposes of the Application of the Sports Blackout Rules ................................................................................................................................ -

Sports Emmy Awards

Sports Emmy Awards OUTSTANDING LIVE SPORTS SPECIAL 2018 College Football Playoff National Championship ESPN Alabama Crimson Tide vs. Georgia Bulldogs The 113th World Series FOX Houston Astros vs Los Angeles Dodgers The 118th Army-Navy Game CBS The 146th Open NBC/Golf Channel Royal Birkdale The Masters CBS OUTSTANDING LIVE SPORTS SERIES NASCAR on FOX FOX/ FS1 NBA on TNT TNT NFL on FOX FOX Deadline Sunday Night Football NBC Thursday Night Football NBC 8 OUTSTANDING PLAYOFF COVERAGE 2017 NBA Playoffs on TNT TNT 2017 NCAA Men's Basketball Tournament tbs/CBS/TNT/truTV 2018 Rose Bowl (College Football Championship Semi-Final) ESPN Oklahoma vs. Georgia AFC Championship CBS Jacksonville Jaguars vs. New England Patriots NFC Divisional Playoff FOX New Orleans Saints vs. Minnesota Vikings OUTSTANDING EDITED SPORTS EVENT COVERAGE 2017 World Series Film FS1/MLB Network Houston Astros vs. Los Angeles Dodgers All Access Epilogue: Showtime Mayweather vs. McGregor [Showtime Sports] Ironman World Championship NBC Deadline[Texas Crew Productions] Sound FX: NFL Network Super Bowl 51 [NFL Films] UFC Fight Flashback FS1 Cruz vs. Garbrandt [UFC] 9 OUTSTANDING SHORT SPORTS DOCUMENTARY Resurface Netflix SC Featured ESPNews A Mountain to Climb SC Featured ESPN Arthur SC Featured ESPNews Restart The Reason I Play Big Ten Network OUTSTANDING LONG SPORTS DOCUMENTARY 30 for 30 ESPN Celtics/Lakers: Best of Enemies [ESPN Films/Hock Films] 89 Blocks FOX/FS1 Counterpunch Netflix Disgraced Showtime Deadline[Bat Bridge Entertainment] VICE World of Sports Viceland Rivals: -

A CHRONOLOGY of PRO FOOTBALL on TELEVISION: Part 2

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 26, No. 4 (2004) A CHRONOLOGY OF PRO FOOTBALL ON TELEVISION: Part 2 by Tim Brulia 1970: The merger takes effect. The NFL signs a massive four year $142 million deal with all three networks: The breakdown as follows: CBS: All Sunday NFC games. Interconference games on Sunday: If NFC team plays at AFC team (example: Philadelphia at Pittsburgh), CBS has rights. CBS has one Thanksgiving Day game. CBS has one game each of late season Saturday game. CBS has both NFC divisional playoff games. CBS has the NFC Championship game. CBS has Super Bowl VI and Super Bowl VIII. CBS has the 1970 and 1972 Pro Bowl. The Playoff Bowl ceases. CBS 15th season of NFL coverage. NBC: All Sunday AFC games. Interconference games on Sunday. If AFC team plays at NFC team (example: Pittsburgh at Philadelphia), NBC has rights. NBC has one Thanksgiving Day game. NBC has both AFC divisional playoff games. NBC has the AFC Championship game. NBC has Super Bowl V and Super Bowl VII. NBC has the 1971 and 1973 Pro Bowl. NBC 6th season of AFL/AFC coverage, 20th season with some form of pro football coverage. ABC: Has 13 Monday Night games. Do not have a game on last week of regular season. No restrictions on conference games (e.g. will do NFC, AFC, and interconference games). ABC’s first pro football coverage since 1964, first with NFL since 1959. Main commentary crews: CBS: Ray Scott and Pat Summerall NBC: Curt Gowdy and Kyle Rote ABC: Keith Jackson, Don Meredith and Howard Cosell.