Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View the Channel Line-Up

SAINT ANSLEM COLLEGE - HD Channel Line Up Network Channel # Description WBIN - HD 7 Local, NH News WBZ - HD CBS 8 CBS Boston, Local News WCVB-HD ABC 9 ABC Boston, Local News WENH-HD 10 NH Public Television WENH-HD2 11 Maine Public Television WFXT-HD FOX 12 Fox25 Boston, Local News WHDH-HD 13 Local, Boston News Channel 7 WLVI-HD 14 Local News, Boston WMFP-HD 15 Local News, Boston/Lawrence WMUR-HD 16 Local News, Manchester, NH WNEU-HD 17 Telemundo Boston WBTS-HD NBC 18 NBC Boston WSBK-HD 19 my38, CBS affiliate WUNI-HD 20 Univision WUTF-HD 21 uniMas Boston WWDP-HD 22 Evine, Home Shopping CKSH-SD 23 ICI Tele - Montreal Public Television WYDN-SD 24 Christian Programming WFXZ-CD 25 TV Azteca NESN HD 26 New England Sports Network A&E HD 27 Documentaries, Drama, Reality TV CNBC HD 28 Business News & Financial Market Coverage CNN HD 29 24/7 News CNN HN HD 30 CNN Headline News CSNNE BHD 31 Comcast SportsNet New England DISNEY HD 32 Family Friendly, Original shows and movies DSC HD 33 Discovery ESPN HD 34 Worldwide Leader in Sports ESPN2 HD 35 Worldwide Leader in Sports - additional coverage FOOD HD 36 Food Network FOXNEWS HD 37 Breaking & Latest News, Current Events Freeform - TV Series & programming for teens and FREEFRM HD 38 young adults FX HD 39 Fox - Comedy, Drama, Movies GOLF HD 40 Golf Channel HGTV HD 41 Home and Garden Network LIFE HD 42 Lifetime Channel - Female Focused Programming MSNBC HD 43 News Coverage and Political Commentary MTV HD 44 Music, Reality, Drama, Comedies Nickelodeon - Family friendly, programming for NICK HD 45 children -

TVP 1 TVP 2 TVN Polsat TV4 TV 6 TVN Siedem TV PULS

STANDARD MEDIUM EXTRA STANDARD EXTRA NAZWA NR NAZWA NR MEDIUM (106) (146) (176) (106) (146) (176) OGÓLNE 15 17 17 Nat Geo Wild 304 TVP 1 001 Animal Planet 305 TVP 2 002 Discovery Channel 306 TVN 003 Discovery Channel 307 Polsat 004 Discovery Science 308 TV4 005 Discovery Turbo Xtra 309 TV 6 006 ID Investigation Discovery 310 TVN Siedem 007 Travel Channel 311 TV PULS 008 BBC Earth 312 TV PULS 2 009 Fokus TV 313 Tele 5 010 RT Documentary 314 TV TRWAM 011 Edusat 315 TTV 012 ROZRYWKA 6 12 15 TVP Polonia 013 TVP Rozrywka 400 Polonia 1 014 TVN Turbo 401 Polsat 2 015 TVN Style 402 TVN 098 Domo+ 403 Polsat 099 Kuchnia+ 404 INFORMACYJNE 12 16 16 BBC Brit 405 TVP Info 100 BBC Lifestyle 406 TVN 24 101 Discovery Life Channel 407 TVN 24 Biznes i Świat 102 TLC 408 TVN Meteo Active 103 Polsat Cafe 409 Polsat News 104 Polsat Play 410 Polsat News 2 105 Food Network 411 TVS 106 ATM Rozrywka 412 BBC World News 108 iTV 413 CNBC 109 iPol 414 Russia Today 110 SPORT 2 6 8 France 24 ENG 111 Eurosport 500 Biełsat TV 112 Eurosport 2 501 Ukraine Today 113 nSport 502 Kazakh TV 114 Polsat Sport 503 Press TV 115 Polsat Sport Extra 504 Arirang 116 Polsat Sport News 505 FILMY I SERIALE 2 8 18 TVP Sport 506 Stopklatka.tv 200 Orange Sport 507 alekino+ 201 DZIECI 1 8 10 Romance TV 202 TVP ABC 600 MGM 203 MiniMini+ 601 FOX 204 Teletoon+ 602 FOX Comedy 205 Disney Channel 603 Kino Polska 206 Disney Junior 604 Polsat Film 207 Disney XD 605 Polsat Romans 208 Nickelodeon HD 606 TVP Seriale 209 Nickelodeon Polska 607 Comedy Central 210 Nick Jr 608 Comedy Central Family 211 Cbeebies -

•Fawmassy Channel Lineup 8.5X14 V2

WATCH IT ALL 197 PVR CHANNELS * Includes all channels from Watch a lot more Never miss a moment with your personal video recorder. 498 SportsMax 1 HD Record your favourite movies or TV series to watch whenever 499 SportsMax 2 HD 501 HBO Signature HD 505 HBO Plus Ea HD 507 HBO Family Ea HD 509 HBO Caribbean Ole HD 515 MAX Prime HD CHANNEL 517 MAX Caribbean HD ACTIVE CHANNEL LIST 521 MAX Up HD 522 Fox 1 HD Cool features you can do with your TV service. 524 Fox Aion HD 526 Fox Movies HD 528 Fox Comedy HD LINEUP 530 Fox Family HD • You can see your channels by genre category 532 Fox Cinema (Sports, Children’s, HD) 534 Fox Classics • ADD ON PACKAGES • Go to Menu MAXPAK ADD ON PACKAGE • Press Enter 498 SportsMax 1 HD • Enter is found underneath the number 9 499 SportsMax 2 HD • 80+ HD HBO & MAX COMBO CHANNELS 501 HBO Signature HD • 505 HD 507 HD • Go to menu 509 HBO Caribbean Ole HD 515 MAX Prime HD • 517 MAX Caribbean HD • 521 MAX Up HD • HBO ADD ON PACKAGE • Click OK 501 HBO Signature HD • 505 HD 507 HD channels accordingly 509 HBO Caribbean Ole HD MAX ADD ON PACKAGE • Set Parental controls to block programs on all channels 515 MAX Prime HD that are higher than the control rating you have set 517 MAX Caribbean HD • 521 MAX Up HD FOX MOVIES ADD ON PACKAGE 522 Fox 1 HD COMING SOON 524 HD 526 Fox Movies HD 528 Fox Comedy HD exciting features coming down the pipeline. -

LISTA KANALOW LCN 01-07-17 -Korbank

LISTA KANAŁÓW I N T E R N E T T E L E W I Z J A T E L E F O N obowiązuje od 01.07.2017r. NAZWA NR STANDARD HD MEDIUM HD EXTRA HD NAZWA NR STANDARD HD MEDIUM HD EXTRA HD (124) (166) (193) (124) (166) (193) OGÓLNE 17 17 17 Russia Today Doc 314 ETV 315 TVP 1 001 Polsat DOKU 316 TVP 2 002 TVN 003 ROZRYWKA 11 16 19 Polsat 004 TVP Rozrywka 400 TV4 005 TVN Turbo 401 TV 6 006 TVN Style 402 TVN Siedem 007 Domo+ HD 403 TV PULS 008 Kuchnia+ 404 TV PULS 2 009 BBC Brit 405 TV TRWAM 011 BBC Lifestyle 406 TTV 012 Discovery Life 407 TVP Polonia 013 TLC 408 Polonia 1 014 Polsat Cafe 409 Polsat 2 015 Polsat Play 410 Tele 5 016 Food Network 411 Zoom TV 022 ATM Rozrywka 412 WP1 023 TO!TV 413 INFORMACJE 13 16 16 Adventure 414 Wellbeing 416 TVN 24 Biznes i Świat 017 Nowa TV 417 HGTV 018 Metro 418 TVP Info 100 Super Polsat 419 TVN 24 101 Polsat News 104 SPORT 7 7 Polsat News 2 105 Eurosport 1 500 TVS HD 106 Eurosport 2 501 BBC World News 108 nSport 502 CNBC 109 Polsat Sport 503 Russia Today 110 Polsat Sport Extra 504 France 24 ENG 111 Polsat Sport News 505 Biełsat TV 112 TVP Sport 506 UA TV 113 Polsat Sport Fight 507 Kazakh TV 114 DLA DZIECI 1 9 12 Press TV 115 Arirang 116 TVP ABC 600 MiniMini+ 601 FILMY I SERIALE 3 10 19 Teletoon+ 602 Stopklatka.tv 200 Disney Channel 603 ale kino+ 201 Disney Junior 604 Romance TV 202 Disney XD 605 AMC 203 Nickelodeon 606 FOX 204 Nickelodeon Polska 607 FOX Comedy 205 Nick Jr 608 Kino Polska 206 Cbeebies 609 Polsat Film 207 Polsat JimJam 610 Polsat Romans 208 Top Kids 611 TVP Seriale 209 MUZYKA 17 18 25 Comedy Central 210 Comedy -

Chaines De La France

Chaines de la France CORONAVIRUS TF1 TF1 HEURE LOCALE -6 M6 M6 HEURE LOCALE -6 FRANCE O FRANCE 0 -6 FRANCE 1 ST-PIERRE ET MIQUELON FRANCE 2 FRANCE 2-6 FRANCE 3 FRANCE 3 HEURE LOCALE -6 FRANCE 4 FRANCE 4-6 FRANCE 5 FRANCE 5-6 BFM LCI EURONEWS TV5 CNEWS FRANCE 24 LCP PARI C8 C8 -6 W9 W9 HEURE LOCALE -6 FILM DE LA SÉRIE TF1 6TER PREMIÈRE DE PARIS 13E RUE TFX COMÉDIE PLUS DISTRICT DU CRIME SYFY FR ALTICE STUDIO POLAIRE + CANAL PARAMOUNT DÉCALE PARAMOUNT CLUB DE SÉRIE WARNER BREIZH NOVELAS NOLLYWOOD FR ÉPIQUE DE NOLLYWOOD A + TCM CINÉMA TMC TEVA HISTOIRE DE LA RCM AB1 CSTAR ACTION E! CHERIE 25 NRJ 12 OCS GEANTS OCS CHOC OCS MAX CANAL + CANAL + DECALE SÉRIE CANAL + CANEL + FAMILLE CINÉ + PREMIER CINÉ + FRISSON CINÉ + ÉMOTION CINÉ + CLASSIQUE CINÉ + FAMIZ CINÉ + CLUB ARTE USHUAIA VOYAGE GÉOGRAPHIQUE NATIONALE NATIONAL WILD CHAÎNE DE DÉCOUVERTE ID DE DÉCOUVERTE FAMILLE DE DÉCOUVERTE DÉCOUVERTE SC MUSÉE SAISONS CHASSE ET PECHE ANIMAUX PLANETE + PLANETE + CL PLANÈTE A ET E RMC DECOUVERTE TOUTE LHISTOIRE HISTOIRE MON TÉLÉVISEUR ZEN CSTAR HITS BELGIQUE PERSONNES NON STOP CLIQUE TV VICE TV RANDONNÉE RFM FR MTV DJAZZ MCM TRACE NRJ HITS MTV HITS MUSIQUE M6 Voici la liste des postes en français Québec inclus dans le forfait Diablo Liste des canaux FRENCH Québec TVA MONTRÉAL TVA MONTRÉAL WEB TVA SHERBROOKE TVA QUÉBEC TVA GATINEAU TVA TROIS RIVIERE WEB TVA HULL WEB TVA OUEST NOOVO NOOVO SHERBROOKE WEB NOOVO TROIS RIVIERE WEB RADIO CANADA MONTRÉAL ICI TELE WEB RADIO CANADA OUEST RADIO CANADA VANCOUVER RADIO CANADA SHERBROOKE RADIO CANADA QUÉBEC RADIO CANADA -

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List Australia FOX Sport 502 FOX LEAGUE HD Australia FOX Sport 504 FOX FOOTY HD Australia 10 Bold Australia SBS HD Australia SBS Viceland Australia 7 HD Australia 7 TV Australia 7 TWO Australia 7 Flix Australia 7 MATE Australia NITV HD Australia 9 HD Australia TEN HD Australia 9Gem HD Australia 9Go HD Australia 9Life HD Australia Racing TV Australia Sky Racing 1 Australia Sky Racing 2 Australia Fetch TV Australia Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Rugby League 1 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 2 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 3 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 1HD Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 2HD Australia -

Układ Kanałów Platformy CANAL+

1 TVN HD HD 48 Cinemax HD HD 90 MiniMini+ HD HD 139 StudioMed TV HD 2 TVN 7 HD HD 49 Cinemax 2 HD HD 91 teleTOON+ HD HD 140 Kuchnia+ HD HD 3 TVN Style HD HD 50 HBO HD HD 92 Disney Junior 141 Domo+ HD HD 4 TVN Turbo HD HD 51 HBO2 HD HD 93 Nick Jr. 142 Food Network HD HD 5 TTV HD HD Cinemax HBO, 52 HBO3 HD HD 94 Cbeebies 143 BBC Lifestyle HD HD 6 TVN 24 HD HD 95 TVP ABC 144 Polsat Cafe HD HD od 16.03.2021 r. od 16.03.2021 7 Polsat HD HD 53 Ale kino+ HD HD 96 Baby TV 145 TLC HD HD 8 TV4 HD HD 54 FOX HD HD 97 Disney Channel HD HD 146 Discovery Life HD HD 9 CANAL+ PREMIUM HD HD 55 FOX Comedy HD HD 98 Disney XD 147 ID HD HD dzieci 10 Polsat 2 HD HD 56 AXN HD HD 99 Nicktoons HD HD 148 Lifetime HD HD 11 TVP 1 HD HD 57 NOVELAS+ HD 100 Nickelodeon 149 Crime + Investigation Polsat HD HD 12 TVP 2 HD HD 58 AMC HD HD 101 Cartoon Network HD 150 MTV Polska HD HD 13 TVP HD HD 59 Romance TV HD HD 102 Boomerang HD HD 151 Nat Geo People HD HD 14 TVP Seriale 60 Sundance TV HD HD 103 Polsat JimJam 152 E! Entertainment HD HD 15 TVP Info HD HD 61 Polsat Film HD HD 104 Da Vinci 153 Polsat Seriale HD HD 16 TVP Kultura HD 62 Comedy Central HD HD 105 teleTOON+ HD HD 155 TVC 17 TVP Polonia HD 63 Paramount Channel HD HD 106 MiniMini+ HD HD 156 NOWA TV HD film ogólne/informacja 18 TVP Historia 64 Kino Polska HD HD 157 TVN Style HD HD 19 TVP Rozrywka 65 13 Ulica HD HD 107 CANAL+ Sport 3 HD HD 158 TV OKAZJE 20 TV Puls HD HD 66 Sci fi HD HD 108 CANAL+ Sport 4 HD HD 159 HOME TV 21 Polsat News HD HD 67 Kino TV HD HD 109 CANAL+ 4K Ultra HD 4K 160 MTV Music 24 22 TVN 24 BiS -

Digicel Play Channel Guide.Indd

Play Plus Premium cont’d. Enjoy Your New Features 306 Fox Soccer Channel HD Quick Tips for Your 307 Fox Sports 2 HD 604 Fox Deportes HD New TV Service WORLDVIEW + Create a list of your Favourite Channels Highlight the channel you want to save in the TV Guide or 427 E! Lat. 608 CCTV 9 Mini Guide and then press on your remote. A heart icon 432 I-Sat 621 Eurochannel Watch Live TV Easily! 510 Euronews 707 MTV Lat. will then appear next to the channel. 515 France 24 712 VH1 Lat. HD 516 NHK World HD Don’t miss your favourite shows with your Personal CHANNEL 602 Telemundo HD The Main Menu button will allow you to easily go Video Recorder (PVR) 604 Fox Sports Deportes HD 605 CNN En Espanol to TV Guide, On Demand, My TV, Search, Support, To record a show you’re currently watching, simply press the 607 CCTV 4 Settings and My Account. Record button on your remote. GUIDE KIDS + TV Easily fi nd what you want to watch by pressing To schedule a recording, fi nd the show you wish to record 201 Disney Channel 207 ToonCast GUIDE the TV Guide button on your remote. This feature using the TV Guide or Mini Guide and then press the Record 202 Disney XD 209 Cartoon Network HD will also allow you to fi lter by Favourites or by button on your remote. 203 Disney Junior 210 Baby TV Genre. 204 Nickelodeon HD 211 Baby First TV 205 Boomerang 213 Smile of A Child If the programme is part of a series, you will be given the 206 Discovery Kids 214 Nick Jr Press the i button on your remote to bring up the option to record the series or a single episode. -

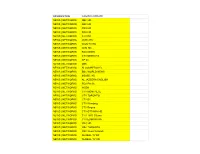

Lp. Program 1 TVP 1 HD 2 TVP 2 HD 3 TVP HD 4 TV4 HD 5 Polsat HD 6 TVN HD 7 TV Puls HD 8 TVN 7 HD 9 Super Polsat 10 Tele5 HD 11 P

Lp. Program 1 TVP 1 HD 2 TVP 2 HD 3 TVP HD 4 TV4 HD 5 Polsat HD 6 TVN HD 7TV Puls HD 8 TVN 7 HD 9 Super Polsat 10 Tele5 HD 11 Polsat 2 HD 12 PULS 2 HD 13 Nowa TV HD 14 TV6 15 ZOOM TV HD 16 METRO HD 17 WP HD 18 TTV HD 19 TVS HD 20 TVP Polonia 21 TVP Kultura 22 Polonia1 23 TVN Fabuła HD 24 FilmBox 25 Kino Polska 26 AXN HD 27 AXN Spin HD 28 AXN White 29 AXN Black 30 Polsat Film HD 31 ale kino+ HD 32 Paramount Channel HD 33 Comedy Central HD 34 Comedy Central Family 35 TNT 36 FOX HD 37 FOX Comedy HD 38 CBS Action 39 CBS Europa HD 40 TVP Seriale 41 Romance TV HD 42 Sundance TV HD 43 Stopklatka HD 44 Polsat Romans 45 TVP Info HD 46 TVP 3 47 Polsat News HD 48 TVN 24 HD 49 Polsat News 2 50 TVN 24 BiS 51 TV Republika 52 Superstacja 53 TVP ABC 54 JimJam Polsat 55 MiniMini+ HD 56 Baby First TV 57 Nick Jr. 58 Nickelodeon 59 Cartoon Network 60 Disney Channel HD 61 Disney XD 62 Disney Junior 63 Da Vinci Learning 64 Boomerang 65 teleTOON+ HD 66 Top Kids HD 67 TVP Sport HD 68 nSport+ HD 69 Polsat Sport HD 70 Polsat Sport Extra HD 71 Polsat Sport News HD 72 Eurosport 1 HD 73 Eurosport 2 HD 74 SportKlub 75 FightKlub HD 76 Extreme Sports Channel HD 77 Motowizja HD 78 TVN Style HD 79 TVN Turbo HD 80 BBC Lifestyle HD 81 BBC HD 82 BBC Brit 83 ID HD 84 TLC HD 85 Polsat Cafe HD 86 Lifetime HD 87 CI Polsat 88 Fashion TV HD 89 DOMO+ HD 90 kuchnia+ HD 91 Food Network HD 92 8TV 93 TVP Rozrywka 94 ATM Rozrywka 95 HGTV 96 DTX HD 97 Discovery Life 98 HISTORY HD 99 CBS Reality 100 Polsat Play HD 101 National Geographic HD 102 Nat Geo Wild HD 103 Nat Geo People HD 104 -

Channels List

INFORMATION COVID19 UPDATE NEWS | NETWORKS NBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS ABC HD NEWS | NETWORKS CBS HD NEWS | NETWORKS FOX HD NEWS | NETWORKS CTV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CNBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS WGN TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CNN HD NEWS | NETWORKS FOX NEWS NEWS | NETWORKS CTV NEWS HD NEWS | NETWORKS CP 24 NEWS | NETWORKS BNN NEWS | NETWORKS BLOOMBERG HD NEWS | NETWORKS BBC WORLD NEWS NEWS | NETWORKS MSNBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS AL JAZEERA ENGLISH NEWS | NETWORKS FOX Pacific NEWS | NETWORKS WSBK NEWS | NETWORKS CTV MONTREAL NEWS | NETWORKS CTV TORONTO NEWS | NETWORKS CTV BC NEWS | NETWORKS CTV Winnipeg NEWS | NETWORKS CTV Regina NEWS | NETWORKS CTV OTTAWA HD NEWS | NETWORKS CTV TWO Ottawa NEWS | NETWORKS CTV EDMONTON NEWS | NETWORKS CBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS CBC TORONTO NEWS | NETWORKS CBC News Network NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV BC NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV CALGARY NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV MONTREAL NEWS | NETWORKS CITY TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CITY VANCOUVER NEWS | NETWORKS WBTS NEWS | NETWORKS WFXT NEWS | NETWORKS WEATHER CHANNEL USA NEWS | NETWORKS MY 9 HD NEWS | NETWORKS WNET HD NEWS | NETWORKS WLIW HD NEWS | NETWORKS CHCH NEWS | NETWORKS OMNI 1 NEWS | NETWORKS OMNI 2 NEWS | NETWORKS THE WEATHER NETWORK NEWS | NETWORKS FOX BUSINESS NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 10 Miami NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 10 San Diego NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 12 San Antonio NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 13 HOUSTON NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 2 ATLANTA NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 4 SEATTLE NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 5 CLEVELAND NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 9 ORANDO HD NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 6 INDIANAPOLIS HD NEWS | NETWORKS -

TELETEMAT TELEMIX TELEKOMUNIKACJA On-Line, Później Widzowie Doceniają Jak Technologia Albo Wcale Naziemną TV Zmieni Edukację?

TELETEMAT TELEMIX TELEKOMUNIKACJA On-line, później Widzowie doceniają Jak technologia albo wcale naziemną TV zmieni edukację? maj/czerwiec 2020 cena 14,99 zł (w tym 8% VAT) 5 euro ISSN 2299-9248 5/6 (203) REKLAMA TELEWIZJA CYFROWA TELEKOMUNIKACJA NOWE TECHNOLOGIE PRAWO I BIZNES 4 ZAPRASZAMY NA STRONĘ WWW.TELEKABEL.PL Andrzej Konaszewski Sekretarz Redakcji COVIDus vobiscum amieszaniu, jakiego narobił Na decyzję co prawda nie miał bezpośredniego COVID-19, istota tyleż niewi- wpływu COVID, tylko ogólna zapaść w biznesach dzialna co złośliwa, końca nie tego operatora. Wirus jednak z pewnością nie widać. Nieczęsto zdarza się, przyczyni się wzrostu zainteresowania współ- by coś, czego gołym okiem nie pracą z Astrą. Raczej należy się spodziewać widać i co bez człowieka żyć nie odpływu nadawców z satelitów (bankructwa, może, wywracało do góry nogami brak klientów). Pandemia wreszcie mocno Zwcześniejsze plany, czy to organizacyjne, czy wpłynęła na rynek telewizorów. Spowodowa- biznesowe. Praktycznie wszystkie konferencje ła bowiem odwołanie tegorocznych ważnych branżowe na świecie pozmieniały swoje terminy imprez sportowych, a co za tym idzie mniejsze na miesiące powirusowe, a przynajmniej licząc zainteresowanie zakupem telewizorów, który na to, że zaraza do tego czasu ustąpi. Te, które to zawsze Igrzyska Olimpijskie, mistrzostwa terminu nie zmieniły, postawiły niczym piłkarska FIFA czy UEFA nakręcają. Ponadto związane Ekstraklasa na mecze bez udziału stadionowej z pandemią pogorszenie warunków fi nansowych widowni, ale za to z widownią on-line. Plany wielu Polaków ogranicza wybór telewizora jako biznesowe zmienia także satelitarna spółka SES, artykułu pierwszej potrzeby. LCD, UHD, 4K i 8K wprowadzając totalną reorganizację w struk- zalegają więc w magazynach, a nam pozostaje turach i likwidując m.in. -

Consolidated National Subscription TV Share and Reach National

Consolidated National Subscription TV Share and Reach National Share and Reach Report - Subscription TV Homes only Week 10 2021 (28/02/2021 - 06/03/2021) 18:00 - 23:59 Total Individuals - Including Guests Channel Share Of Viewing Reach Weekly 000's % TOTAL PEOPLE ABC TV 7.0 1529 ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus 1.1 671 ABC ME 0.1 212 ABC NEWS 0.9 577 Seven + AFFILIATES 13.8 2488 7TWO + AFFILIATES 1.1 426 7mate + AFFILIATES 1.2 683 7flix + AFFILIATES 0.5 378 Nine + AFFILIATES* 17.5 2746 GO + AFFILIATES* 1.0 597 Gem + AFFILIATES* 0.9 462 9Life + AFFILIATES* 0.8 324 9Rush + AFFILIATES* 0.2 143 10 + AFFILIATES* 6.8 2007 10 Bold + AFFILIATES* 1.2 422 10 Peach + AFFILIATES* 1.3 559 10 Shake + AFFILIATES* 0.1 99 Sky News on WIN + AFFILIATES* 0.3 172 SBS 2.6 1210 SBS VICELAND 0.6 513 SBS Food 0.4 363 NITV 0.1 247 SBS World Movies 0.2 352 A&E 0.5 307 A&E+2 0.2 173 Animal Planet 0.3 237 BBC Earth 0.3 286 BBC First 0.5 324 beIN SPORTS 1 0.1 88 beIN SPORTS 2 0.1 88 beIN SPORTS 3 0.1 85 Boomerang 0.1 68 BoxSets 0.1 70 Cartoon Network 0.1 50 CBeebies 0.3 127 Club MTV 0.1 148 CMT 0.0 43 crime + investigation 0.7 270 Discovery Channel 1.1 574 Discovery Channel+2 0.2 259 Discovery Turbo 0.5 254 Discovery Turbo+2 0.2 157 E! 0.2 236 E! +2 0.0 124 ESPN 0.3 179 ESPN2 0.1 131 FOX Arena 0.4 414 FOX Arena+2 0.1 197 FOX Classics 1.1 493 FOX Classics+2 0.3 194 FOX Comedy 0.5 345 Excludes Tasmania Data © OzTAM Pty Limited 2020.