The Fictionality of Time in Modern Tragedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

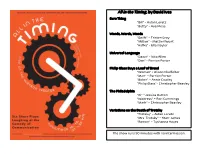

All in the Timing, by David Ives

All in the Timing, by David Ives Sure Thing “Bill” - Aidan Loretz “Betty” - Ava Moss Words, Words, Words “Swift” – Tristen Gray “Milton” - Mattie Mount “Kafka” - Ella Naylor Universal Language “Dawn” - Nita Allen “Don” - Perrion Porter Philip Glass Buys a Loaf of Bread “Woman” - Alison Clodfelter “Man” – Perrion Porter “Baker” – Annie Cowley “Philip Glass”- Christopher Beasley The Philadelphia “Al” –Jessica Dutton “Waitress” – Rori Cummings “Mark” – Christopher Beasley Variations on the Death of Trotsky “Trotsky” – Aidan Loretz “Mrs. Trotsky” – Starr James “Ramon” – Tyshanna Hayes The show runs 90 minutes with no intermission. Director’s Notes Director/Choreographer – Jesse Graham Galas Stage Manager – AE Ray All in the Timing is, at its core, a series of plays Assistant Stage Managers – Ava Moss, Samantha Harriss asking, “What if?” What if you got the chance to Technical Director – Josh Webb start over every time you said the wrong thing? Lights/Set Designer – Josh Webb What if you put some monkeys in a room with Assistant Technical Director – Mike Merluzzi some typewriters…could they really come up with Costume Designers one of the greatest plays ever written? What if “Sure Thing”– Lawson Lee everyone spoke the same language? Would that “Words, Words, Words” – Chevez Smith end all communication breakdowns forever? What “Universal Language” – Cameron McWhorter if you could get inside the mind of composer Philip “Philip Glass Buys a Loaf of Bread” – Jolee Masson Glass…has the smallest act of buying a loaf of “The Philadelphia” – Starr -

Greek Theory of Tragedy: Aristotle's Poetics

Greek Theory of Tragedy: Aristotle's Poetics The classic discussion of Greek tragedy is Aristotle's Poetics. He defines tragedy as "the imitation of an action that is serious and also as having magnitude, complete in itself." He continues, "Tragedy is a form of drama exciting the emotions of pity and fear. Its action should be single and complete, presenting a reversal of fortune, involving persons renowned and of superior attainments, and it should be written in poetry embellished with every kind of artistic expression." The writer presents "incidents arousing pity and fear, wherewith to interpret its catharsis of such of such emotions" (by catharsis, Aristotle means a purging or sweeping away of the pity and fear aroused by the tragic action). The basic difference Aristotle draws between tragedy and other genres, such as comedy and the epic, is the "tragic pleasure of pity and fear" the audience feel watching a tragedy. In order for the tragic hero to arouse these feelings in the audience, he cannot be either all good or all evil but must be someone the audience can identify with; however, if he is superior in some way(s), the tragic pleasure is intensified. His disastrous end results from a mistaken action, which in turn arises from a tragic flaw or from a tragic error in judgment. Often the tragic flaw is hubris, an excessive pride that causes the hero to ignore a divine warning or to break a moral law. It has been suggested that because the tragic hero's suffering is greater than his offense, the audience feels pity; because the audience members perceive that they could behave similarly, they feel pity. -

“From Strange to Stranger”: the Problem of Romance on the Shakespearean Stage

“From strange to stranger”: The Problem of Romance on the Shakespearean Stage by Aileen Young Liu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English and the Designated Emphasis in Renaissance and Early Modern Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jeffrey Knapp, Chair Professor Oliver Arnold Professor David Landreth Professor Timothy Hampton Summer 2018 “From strange to stranger”: The Problem of Romance on the Shakespearean Stage © 2018 by Aileen Young Liu 1 Abstract “From strange to stranger”: The Problem of Romance on the Shakespearean Stage by Aileen Young Liu Doctor of Philosophy in English Designated Emphasis in Renaissance and Early Modern Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Jeffrey Knapp, Chair Long scorned for their strange inconsistencies and implausibilities, Shakespeare’s romance plays have enjoyed a robust critical reconsideration in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. But in the course of reclaiming Pericles, The Winter’s Tale, Cymbeline, and The Tempest as significant works of art, this revisionary critical tradition has effaced the very qualities that make these plays so important to our understanding of Shakespeare’s career and to the development of English Renaissance drama: their belatedness and their overt strangeness. While Shakespeare’s earlier plays take pains to integrate and subsume their narrative romance sources into dramatic form, his late romance plays take exactly the opposite approach: they foreground, even exacerbate, the tension between romance and drama. Verisimilitude is a challenge endemic to theater as an embodied medium, but Shakespeare’s romance plays brazenly alert their audiences to the incredible. -

|||GET||| All in the Timing Six One-Act Comedies 1St Edition

ALL IN THE TIMING SIX ONE-ACT COMEDIES 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE David Ives | 9780822213963 | | | | | StageAgent Distance Learning Hub The writing is not only very funny, it has density of thought and precision of poetry … All in the Timing is by a master of fun. Monologues from Plays. By the time we get to the end of the play, the bell ringing has forged a model love at first sight — it just takes a long time to get there. Ives is a mordant comic who has put the play back in playwright … A wondrous wordmaster. Buy It Now. Notes: A recent republishing of All in the Timing features an additional 8 one-acts. Two people meet in a cafe and find their way through a conversational minefield as an offstage bell interrupts their false starts, gaffes, and faux pas on the way to falling in love. About this product. Research Playwrights, Librettists, Composers and Lyricists. Words, Words, Words is particularly suitable for schools and play contests. Cheshire, CT. Any Condition Any Condition. Add to cart. Show More Show Less. Search all audition songs. This volume includes Sure Thing and Words, Words, Wordswhich are ideal choices for high school drama contests and one-act festivals. Philadelphia, PA. Finally, after the fourth bell ring, she says that she is not waiting for All in the Timing Six One-Act Comedies 1st edition, and the conversation progresses from there. Shows All in the Timing. All in the Timing guide sections. See all 15 - All listings for this product. Gain full access to show guides, character breakdowns, auditions, monologues and more! Wade Bradford, M. -

Newton Grisham Library Play Script List -By Author

Newton Grisham Library Play Script List -by Author BIN # PLAY # TITLE AUTHOR # MEN # WOMEN # CHILDREN OTHER 73 1570 Manhattan Class Company Class 1 Acts 1991-1992 161 2869 The Boys from Siam Connolly, John Austin 2 161 2876 Fugue Thuna, Lee 3 5 74 1591 Acrobatics Aaron, Joyce; Tarlo, Luna 96 1957 June Groom Abbot, Rick 3 6 99 2016 Play On! Abbot, Rick 3 7 103 2080 Turn For The Nurse, A Abbot, Rick 5 5 30 699 Three Men On A Horse Abbott, G. And J.C. Holm 11 4 34 802 Green Julia Ableman, Paul 2 133 2457 Tabletop Ackerman, Rob 5 1 86 1793 Batting Cage, The Ackermann, Joan 1 3 86 1798 Marcus Is Walking Ackermann, Joan 3 2 88 1825 Off The Map Ackermann, Joan 3 2 101 2051 Stanton's Garage Ackermann, Joan 4 4 10 227 Farewell, Farewell Eugene Ackland, Rodney; Vari, John 3 6 84 1776 Lighting Up The Two-Year Old Aerenson, Benjie 3 167 2970 Dark Matters Aguirre-Sacasa, Roberto 3 1 168 2982 King of Shadows Aguirre-Sacasa, Roberto 2 2 169 2998 The Muckle Man Aguirre-Sacasa, Roberto 5 2 169 3007 Rough Magic Aguirre-Sacasa, Roberto 7 5 doubling 101 2054 Edgar Lee Masters' Spoon River Anthology Aidman, Charles 3 2 101 2054 Spoon River Anthology Aidman, Charles [Adapt. By] 3 2 149 2686 Green Card Akalaitis, JoAnne 6 5 10 221 Fragments Albee, Edward 4 4 19 436 Marriage Play Albee, Edward 1 1 26 604 Seascape Albee, Edward 2 2 30 705 Tiny Alice Albee, Edward 4 1 34 800 The Zoo Story and The Sandbox: Two Short Plays Albee, Edward 34 800 Sandbox, The Albee, Edward 3 2 44 1066 Counting the Ways and Listening: Two Plays Albee, Edward 44 1066 Counting The Ways -

Writing Emotions

Ingeborg Jandl, Susanne Knaller, Sabine Schönfellner, Gudrun Tockner (eds.) Writing Emotions Lettre 2017-05-15 15-01-57 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0247461218271772|(S. 1- 4) TIT3793_KU.p 461218271780 2017-05-15 15-01-57 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0247461218271772|(S. 1- 4) TIT3793_KU.p 461218271780 Ingeborg Jandl, Susanne Knaller, Sabine Schönfellner, Gudrun Tockner (eds.) Writing Emotions Theoretical Concepts and Selected Case Studies in Literature 2017-05-15 15-01-57 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0247461218271772|(S. 1- 4) TIT3793_KU.p 461218271780 Printed with the support of the State of Styria (Department for Health, Care and Science/Department Science and Research), the University of Graz, and the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Graz. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-3793-3. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivs 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative -

“A Me Non Venderà Egli Vesciche”: Questionable Medici and Medicine Questioned in Machiavelli’S Mandragola

“A me non venderà egli vesciche”: Questionable medici and Medicine Questioned in Machiavelli’s Mandragola Tessa Claire Gurney A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Romance Languages (Italian). Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by: Dino Cervigni Valeria Finucci Ennio Rao ABSTRACT “A me non venderà egli vesciche”: Questionable medici and Medicine Questioned in Machiavelli’s La mandragola (Under the direction of Ennio Rao) In Niccolò Machiavelli’s La mandragola, one of the first performed erudite comedies, the ethics of medicine and medical practitioners are continuously called into question. This thesis explores the way in which medicine and medical men are represented in Machiavelli’s comedy, taking into account the time and place in which this comedy was written and performed: early sixteenth-century Florence. I will examine the tropes of the doctor which are represented in the comedy, and draw a link between the negative representations of these common tropes and the humanist medical skeptics. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………...…1 Chapter I. “Non vorrei mi tenessino un cerretano”: Charlatanry and Theatricality at Play in La mandragola…………………………………………...…….3 II. The Early Modern Doctor and His Credulous Clientele……………………………………………………………….…15 A Call for Medical Reform.……………………………………………...16 A Susceptible Target………………………………………………..……21 Proverbial Liars…………………………………………………………..23 -

Online Lecture Note from Dr. Anita Ghosh; HOD Department of English

Online Lecture note from Dr. Anita Ghosh; H.O.D. Department of English; R.D. College, Muzaffarpur. P G Semester-II CC-07, Unit- II Criticism Theory of Tragedy (Classical theories) As the great period of Athenian drama drew to an end at the beginning of the 4th century BCE, Athenian philosophers began to analyze its content and formulate its structure. In the thought of Plato (c. 427–347 BCE), the history of the criticism of tragedy began with speculation on the role of censorship. To Plato (in the dialogue on the Laws) the state was the noblest work of art, a representation (mimēsis) of the fairest and best life. He feared the tragedians’ command of the expressive resources of language, which might be used to the detriment of worthwhile institutions. He feared, too, the emotive effect of poetry, the Dionysian element that is at the very basis of tragedy. Therefore, he recommended that the tragedians submit their works to the rulers, for approval, without which they could not be performed. It is clear that tragedy, by nature exploratory, critical, independent, could not live under such a regimen. Plato is answered, in effect and perhaps intentionally, by Aristotle’s Poetics. Aristotle defends the purgative power of tragedy and, in direct contradiction to Plato, makes moral ambiguity the essence of tragedy. The tragic hero must be neither a villain nor a virtuous man but a “character between these two extremes,…a man who is not eminently good and just, yet whose misfortune is brought about not by vice or depravity, but by some error or frailty [hamartia].” The effect on the audience will be similarly ambiguous. -

Schutz Theatre FT June 2021

THE W. STANLEY SCHUTZ THEATRE COLLECTION: THE COLLEGE OF WOOSTER PRODUCTIONS FINDING TOOL Denise Monbarren June 2021 FINDING TOOL SCHUTZ COLLECTION Box 1 #56 Productions: 1999 X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets AARON SLICK FROM PUNKIN CRICK Productions: 1960 X-Refs. Clippings [about] Flyers, Pamphlets Photographs Playbills Postcards ABIE’S IRISH ROSE Productions: 1945, 1958 X-Refs. Clippings [about] Photographs [of] Playbills Postcards ABOUT WOMEN Productions: 1997 Flyers, Pamphlets Invitations ACT OF MADNESS Productions: 2003 Flyers, Pamphlets THE ACTING RECITALS Productions: 2003, 2004 Flyers, Pamphlets Playbills ADAIR, TOM X-Refs. ADAM AND EVA Productions: 1922 X-Refs. Playbills AESOP’S FALABLES Productions: 1974 X-Refs. Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets Itineraries Notes Photographs [of] Playbills AFRICAN-AMERICAN PERFORMING ARTS FESTIVAL Productions: [n.d.] Playbills AGAMEMNON Productions: 2003 X-Refs. THE AGES OF WOMAN Productions: 1964 Playbills AH, WILDERNESS Productions: 1966, 1987 X-Refs. Photographs [of] Playbills ALABAMA Productions: 1918 X-Refs. Playbills Box 2 ALCESTIS Productions: [1955] X-Refs. Playbills ALICE IN WONDERLAND Productions: 1955, 1974 X-Refs. Artwork [about] Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets Invitations Itineraries Notes ALL IN THE TIMING Productions: 2002 X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location Press Releases ALL MY SONS Productions: 1968, 2006 X-Refs. Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location Invitations Photographs [of] Playbills Postcards Press Releases ALL THE COMFORTS OF HOME Productions: 1912 X-Refs. Playbills ALLARDICE, JAMES See PEACOCK IN THE PARLOR ALMOST, MAINE Productions: 2017 X-Refs. Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location Press Releases Box 3 AMADEUS Productions: [1985] X-Refs. Playbills AMAHL AND THE NIGHT VISITORS Productions: 1969 See also: HELP, HELP, THE GLOBOLINKS! X-Refs. -

Neoclassical Theatre

Theatre History Lecture Notes Neoclassical Theatre Unit Lecture compiled by Justin Eick - Theatrical Education Group Objectives: • Students will Overview – Neoclassical Theatre expand their Neoclassicism was the dominant form Neoclassical theatre as well as the time vocabulary of of theatre in the eighteenth century. It period is characterized by its grandiosity. Neoclassical demanded decorum and rigorous The costumes and scenery were intricate theatre. adherence to the classical unities. and elaborate. The acting is • Students will characterized by large gestures and understand the Classicism is a philosophy of art and life melodrama. impact of that emphasizes order, balance and Neoclassical simplicity. Ancient Greeks were the first Dramatic unities of time, place, and theatre on great classicists - later, the Romans, action; division of plays into five acts; modern society French, English and others produced purity of genre; and the concepts of through analysis classical movements. The Restoration decorum and verisimilitude were taken of historical period marked a Neo-Classical as rules of playwriting, particularly by trends from the movement, modeled on the classics of French dramatists. period. Greece and Rome. • Students will acquire the appropriate Origins skills to The development of the French theatre principles make up what came to be accurately and had been interrupted by civil wars in the called the neoclassical ideal. consistently sixteenth and seventeenth century. perform Stability did not return until around 1625, The transition to the new ideal also Neoclassical when Cardinal Richelieu, Louis XIII’s required that the theatre structure be theatre within prime minister, set out to make France altered. To set an example, Richelieu in the specific the cultural center of Europe. -

Monika Turner

Monika Turner - MPhil in Writing – 300 Word Abstract Threads of Influence: Greek Tragedy and its Relevance to the Contemporary Novel, With Specific Reference to Donna Tartt’s The Secret History And my Novel, The First Seven Years This MPhil concerns the contemporary literary novel and how it has been influenced by the Golden Age of Greek tragedy. It comprises of three parts: the thesis and the novel, hereby presented, and the journal of creative experiences, which was observed at viva. My thesis examines the historical development of Greek tragedy and its structure. It further explores how tragedy has influenced writers through the ages, culminating in the literary tragedy of today. The methodology of tragic form is investigated in the works of writers educated in Greek tragic structure, and also those with no classical background. This thesis aims to show how novelists without a classical education have accessed the tragic form, via threads of literary influence, and utilised it successfully, albeit often unconsciously. My novel, The First Seven Years, is a work of contemporary tragic fiction. It tells the story of one woman’s attempts to do the best for her child. Trapped between raising her young son, Alfie, and caring for an increasingly frail elderly relative, Kate becomes emotionally and physically stretched. When she discovers Alfie has been badly bullied in his failing state school, her attempts to change schools have tragic consequences. Finally, my journal, presented at viva, compiles my creative thoughts, notes and research for both novel and thesis in one portfolio. My original notebooks show much of my novel’s planning and I have included visual images used of characters, buildings, locations, Kate’s photography and Martha’s pottery. -

All in the Timing a Collection of 6 One-Act Plays Written by David Ives

Greetings! All the details you need to know about the show and how to potentially see the show are here, so read on if you’re interested! All in the Timing A collection of 6 One-Act Plays written by David Ives Performing live Friday May 14 @ 4:00 pm Performing live and livestreamed Saturday & Sunday May 15 & 16 @ 2:00 pm Tickets: Performed outdoors in the Carney Amphitheatre for family of the cast/crew and Bellarmine staff only. Sorry we can’t open up tickets to the general public and the student body, but you are welcome to livestream it FOR FREE on the 15th/16th. Email [email protected] saying which date you’ll attend, and the link will be emailed to you ~2 hours before each performance. If you are faculty/staff or a current Bellarmine student, you do not need to send Mr. Marcel and email; the link to the livestream will go out to all Staff & Current Students. Run time is approximately one hour and 40 minutes, no intermission. Show details… Our Very Talented and Funny Cast: Quinn Dembecki, ‘22 Josh Frojelin, ‘21 Nate Lanier, ‘22 Erick Moreno, ‘21 Sadie Meyercord, ‘21 Jamie Penilla, ‘22 Leo Scola, ‘23 Anna Young, ‘23 Michael Young, ‘21 Assistant Directors: Nathan Janda ’23 and Enrique Aguilar ’23 Stage Manager: Fernando Salvador Francisco, ‘21 Stage Crew: Addison Ruiz ’21, Simon Dodge ’22, Liam Saunders ’22, Jakob Lokteff ’22, Tyler Tran ’22, Ben McPheeters ’22, Nicholas Sinn ’22, Adam Ajluni ‘23 Poster Design: Keshav Singh ‘22 Director: Russ Marcel Tech Director: Gregg Carlson Costume Designer: Kathleen O’Brien Director’s Note Written by David Ives between 1987-1994, these 6 separate one-act plays were not meant to be performed outdoors, but we happen to have a unique opportunity to produce a Bellarmine Theatre show in the Carney Amphitheatre.