Appendix to Petition for a Writ of Certiorari Volume 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RHYTHM & BLUES...63 Order Terms

5 COUNTRY .......................6 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................71 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............22 SURF .............................83 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......23 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............85 WESTERN..........................27 PSYCHOBILLY ......................89 WESTERN SWING....................30 BRITISH R&R ........................90 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................30 SKIFFLE ...........................94 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................31 AUSTRALIAN R&R ....................95 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........31 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............96 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND....31 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE......32 POP.............................103 COUNTRY CHRISTMAS................33 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................136 BLUEGRASS ........................33 LATIN ............................148 NEWGRASS ........................35 JAZZ .............................150 INSTRUMENTAL .....................36 SOUNDTRACKS .....................157 OLDTIME ..........................37 EISENBAHNROMANTIK ...............161 HAWAII ...........................38 CAJUN/ZYDECO ....................39 DEUTSCHE OLDIES ..............162 TEX-MEX ..........................39 KLEINKUNST / KABARETT ..............167 FOLK .............................39 Deutschland - Special Interest ..........167 WORLD ...........................41 BOOKS .........................168 ROCK & ROLL ...................43 BOOKS ...........................168 REGIONAL R&R .....................56 DISCOGRAPHIES ....................174 LABEL R&R -

The Clique Song List 2000

The Clique Song List 2000 Now Ain’t It Fun (Paramore) All About That Bass (Meghan Trainor) American Boy (Estelle & Kanye West) Applause (Lady Gaga) Before He Cheats (Carrie Underwood) Billionaire (Travie McCoy & Bruno Mars) Birthday (Katy Perry) Blurred Lines (Robin Thicke) Can’t Get You Out Of My Head (Kylie Minogue) Can’t Hold Us (Macklemore & Ryan Lewis) Clarity (Zedd) Counting Stars (OneRepublic) Crazy (Gnarls Barkley) Dark Horse (Katy Perry) Dance Again (Jennifer Lopez) Déjà vu (Beyoncé) Diamonds (Rihanna) DJ Got Us Falling In Love (Usher & Pitbull) Don’t Stop The Party (The Black Eyed Peas) Don’t You Worry Child (Swedish House Mafia) Dynamite (Taio Cruz) Fancy (Iggy Azalea) Feel This Moment (Pitbull & Christina Aguilera) Feel So Close (Calvin Harris) Find Your Love (Drake) Fireball (Pitbull) Get Lucky (Daft Punk & Pharrell) Give Me Everything (Tonight) (Pitbull & NeYo) Glad You Came (The Wanted) Happy (Pahrrell) Hey Brother (Avicii) Hideaway (Kiesza) Hips Don’t Lie (Shakira) I Got A Feeling (The Black Eyed Peas) I Know You Want Me (Calle Ocho) (Pitbull) I Like It (Enrique Iglesias & Pitbull) I Love It (Icona Pop) I’m In Miami Trick (LMFAO) I Need Your Love (Calvin Harris & Ellie Goulding) Lady (Hear Me Tonight) (Modjo) Latch (Disclosure & Sam Smith) Let’s Get It Started (The Black Eyed Peas) Live For The Night (Krewella) Loca (Shakira) Locked Out Of Heaven (Bruno Mars) More (Usher) Moves Like Jagger (Maroon 5 & Christina Aguliera) Naughty Girl (Beyoncé) On The Floor (Jennifer -

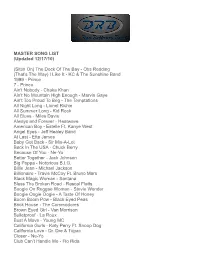

DRB Master Song List

MASTER SONG LIST (Updated 12/17/10) (Sittin On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding (That’s The Way) I Like It - KC & The Sunshine Band 1999 - Prince 7 - Prince Ain't Nobody - Chaka Khan Ain’t No Mountain High Enough - Marvin Gaye Ain’t Too Proud To Beg - The Temptations All Night Long - Lionel Richie All Summer Long - Kid Rock All Blues - Miles Davis Always and Forever - Heatwave American Boy - Estelle Ft. Kanye West Angel Eyes - Jeff Healey Band At Last - Etta James Baby Got Back - Sir Mix-A-Lot Back In The USA - Chuck Berry Because Of You - Ne-Yo Better Together - Jack Johnson Big Poppa - Notorious B.I.G. Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Billionaire - Travie McCoy Ft. Bruno Mars Black Magic Woman - Santana Bless The Broken Road - Rascal Flatts Boogie On Reggae Woman - Stevie Wonder Boogie Oogie Oogie - A Taste Of Honey Boom Boom Pow - Black Eyed Peas Brick House - The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl - Van Morrison Bulletproof - La Roux Bust A Move - Young MC California Gurls - Katy Perry Ft. Snoop Dog California Love - Dr. Dre & Tupac Closer - Ne-Yo Club Can’t Handle Me - Flo Rida Cowboy - Kid Rock Crazy - Gnarles Barkley Crazy In Love - Beyonce ft. Jay Z Dancing In The Streets - Martha and The Vendellas Disco Inferno - The Trammps DJ Got Us Falling In Love - Usher Don’t Stop Believing - Journey Don’t Stop The Music - Rihanna Drift Away - Uncle Kracker Dynamite - Taio Cruz Evacuate The Dance Floor - Cascada Everything - Michael Bublé Faithfully - Journey Feelin Alright - Joe Cocker Fight For Your Right - Beastie Boys Fly Away - Lenny Kravitz Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Free Fallin’ - Tom Petty Funkytown - Lipps, Inc. -

October 25Th 2011

+ HIGH ENERGY/DANCE Brick House, Commodores All Night Long, Lionel Ritchie 1999, Prince Le Freak, CHIC Can’t feel my face, The Weeknd We Are Family, Sister Sledge Shut up and dance with me, Walk the YMCA, The Village People moon Crazy Little Thing Called Love, Queen Uptown Funk, Bruno Mars Love Song, The Cure Footloose, Blake Shelton I'm So Excited, Pointer Sisters Shake it off, Taylor Swift Girls Just Want To Have Fun, Cindy Cupid Shuffle, Cupid Lauper Happy, Pharrell Williams Keep Your Hands To Yourself, Georgia Moves like Jagger, Maroon 5 Satellites I Know You Want Me, Pitbull The House is Rockin', Stevie Ray Vaughn Let's Dance, Lady Gaga 867-5309 (Jenny, Jenny), Tommy Firework, Katy Perry Tutone Let's Go Crazy, Prince The Future's So Bright (I Gotta Wear Blurred Lines, Robin Thicke Shades), Timbuk 3 Get Lucky, Daft Punk Jungle Love, Steve Miller Party Rock Anthem, LMFAO Old Time Rock n' Roll, Bob Seger Gingham Style, Psy Feel Like Makin' Love, Bad Company Don't Stop The Party, Pitbull La Grange, ZZ Top I Gotta Feeling, The Black-Eyed Peas Hotel California, The Eagles Play That Funky Music, Wild Cherry Volcano, Jimmy Buffet Love Shack, B-52s Margaritaville, Jimmy Buffet Hey Ya, Outkast Satisfaction, The Rolling Stones Tubthumpin', Chumbawamba Sweet Caroline, Neil Diamond I Will Survive, Gloria Gaynor She Loves You, The Beatles Brick House, Commodores Twist and Shout, The Beatles California Sun, The Rivieras Jailhouse Rock, Elvis Presley Celebration, Kool and the Gang La Bamba, Richie Valens Hot, Hot, Hot, Buster Poindexter Pretty Woman, Roy Orbison I Feel Good, James Brown Mustang Sally, Wilson Pickett I'm A Believer, Smashmouth Boot Scootin' Boogie, Brooks and Dunn Turn The Beat Around, Vicky Sue Steamroller Blues, James Taylor Robinson Proud Mary, Tina Turner That's The Way I Like It, K.C. -

The Commodores All the Greatest Hits Zip

The Commodores All The Greatest Hits Zip 1 / 5 The Commodores All The Greatest Hits Zip 2 / 5 3 / 5 After winning the university's annual freshman talent contest, they played at fraternity parties as well as a weekend gig at the Black Forest Inn, one of a few clubs in Tuskegee that catered to college students.. The group's most successful period was in the late 1970s and early 1980s when Lionel Richie was co-lead singer.. )The Commodores made a brief appearance in the 1978 film Thank God It's Friday They performed the song 'Too Hot ta Trot' during the dance contest; the songs 'Brick House' and 'Easy' were also played during the movie. There was even a Jazz aspect to one of the groups They wanted to change the name.. Exclusive discount for Prime members The Commodores are an American funk/soul band, which was at its peak in the late 1970s through the mid 1980s.. Ingram, older than the rest of the band, left to serve active duty in Vietnam, and was later replaced by Walter 'Clyde' Orange, who would write or co-write many of their hit tunes.. Feb 05, 2019 Greatest Hits Vinyl Vinyl 4 6 out of 5 stars 599 20th Century Masters: The Best of The Commodores - The Millennium Collection. All Book Of Humayun Ahmed Free - Free Software and Shareware Together, a six-man band was created from which the notable individuals were Lionel Richie, Thomas McClary, and William King from the Mystics; Andre Callahan, Michael Gilbert, and Milan Williams were from the Jays. -

Uptownlive.Song List Copy.Pages

Uptown Live Sample - Song List Top 40/ Pop 24k Gold - Bruno Mars Adventure of A Lifetime - Coldplay Aint My Fault - Zara Larsson All of Me (John Legend) Another You - Armin Van Buren Bad Romance -Lady Gaga Better Together -Jack Johnson Blame - Calvin Harris Blurred Lines -Robin Thicke Body Moves - DNCE Boom Boom Pow - Black Eyed Peas Cake By The Ocean - DNCE California Girls - Katy Perry Call Me Maybe - Carly Rae Jepsen Can’t Feel My Face - The Weeknd Can’t Stop The Feeling - Justin Timberlake Cheap Thrills - Sia Cheerleader - OMI Clarity - Zedd feat. Foxes Closer - Chainsmokers Closer – Ne-Yo Cold Water - Major Lazer feat. Beiber Crazy - Cee Lo Crazy In Love - Beyoncé Despacito - Luis Fonsi, Daddy Yankee and Beiber DJ Got Us Falling In Love Again - Usher Don’t Know Why - Norah Jones Don’t Let Me Down - Chainsmokers Don’t Wanna Know - Maroon 5 Don’t You Worry Child - Sweedish House Mafia Dynamite - Taio Cruz Edge of Glory - Lady Gaga ET - Katy Perry Everything - Michael Bublé Feel So Close - Calvin Harris Firework - Katy Perry Forget You - Cee Lo FUN- Pitbull/Chris Brown Get Lucky - Daft Punk Girlfriend – Justin Bieber Grow Old With You - Adam Sandler Happy – Pharrel Hey Soul Sister – Train Hideaway - Kiesza Home - Michael Bublé Hot In Here- Nelly Hot n Cold - Katy Perry How Deep Is Your Love - Calvin Harris I Feel It Coming - The Weeknd I Gotta Feelin’ - Black Eyed Peas I Kissed A Girl - Katy Perry I Knew You Were Trouble - Taylor Swift I Want You To Know - Zedd feat. Selena Gomez I’ll Be - Edwin McCain I’m Yours - Jason Mraz In The Name of Love - Martin Garrix Into You - Ariana Grande It Aint Me - Kygo and Selena Gomez Jealous - Nick Jonas Just Dance - Lady Gaga Kids - OneRepublic Last Friday Night - Katy Perry Lean On - Major Lazer feat. -

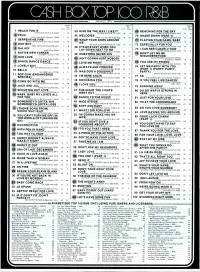

CB-1978-01-07-OCR-Pa

DXTO D CX) R January 7, 1978 Weeks Weeks Weeks On On On 12/31 Chart 12/31 Chart 12/31 Chart 1 REACH FOR IT 35 KISS ME THE WAY I LIKE IT 69 REACHING FOR T HE SKY GEORGE DUKE (Epic 8-50463) 1 10 GEORGE McCRAE (TK -1024) 36 PEABO la522> 75 4 2 FFUN 36 MELODIES 70 SHAKE DOWN (PART 1) CON FUNK SHUN (Mercury 73959) 3 11 MADE IN U.S.A. (Delite DE -900) 34 13 BLACK ICE (HDM-503) 70 8 3 SERPENTINE FIRE 37 WRAP YOUR ARMS AROUND 71 PLAYING YOUR GAME, BABY EARTH, WIND & FIRE (Columbia 3-10625) 2 13 ME BARRY WHITE (20th Century TC -2361) 77 2 4', OOH BOY KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND (TK 1022) 43 72 ESPECIALLY FOR YOU ROSE ROYCE (Whitfield/WB 8491) 5 8 38 IT'S WHEN MANCHILD (Chi Sound/UA CH-XW 1112) 72 7 5 GALAXY ECSTASY YOU LAY DOWN 73 I CAN SEE CLEARLY NOW WAR (MCA 40820) 6 8 NEXT TO ME RAY CHARLES (Atlantic 3443) 74 4 BARRY WHITE (20th Century T-2350) 38 23 6 NATIVE NEW YORKER 74 DON'T LET ME BE ODYSSEY (RCA PB11129) 4 13 39 CHEATERS NEVER WIN LOVE COMMITTEE (Gold Mind 4033) 10 7 OUR LOVE GM 39 MISUNDERSTOOD 40 SANTA ESMERALDA/LEROY GOMEZ NATALIE COLE (Capitol 4059) 8 9 AIN'T GONNA HURT NOBODY (Casablanca NB902) 78 4 BRICK (Bang 735) 44 it DANCE DANCE DANCE 75 YOU ARE MY FRIEND CHIC (Atlantic 3435) 10 11 41 LOVE ME RIGHT PATTI LaBELLE (Epic 8-50487) 82 2 DENISE LaSALLE (ABC 12312) 46 9 LOVELY DAY 76 LET ME PARTY WITH YOU BILL WITHERS (Columbia 3-10627) 7 12 42 ALWAYS AND FOREVER 10 BELLE HEATWAVE (Epic 50490) 48 (PART 1) (PARTY, PARTY, AL GREEN (Hi H 77505) 9 11 43 WAS DOG A DOUGHNUT PARTY) 11 BOP GUN (ENDANGERED CAT STEVENS (A&M 1971-S) 41 BUNNY SIGLER -

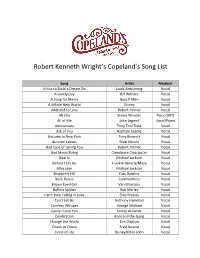

Robert Kenneth Wright's Copeland's Song List

Robert Kenneth Wright’s Copeland’s Song List Song Artist Medium A Kiss to Build a Dream On Louis Armstrong Vocal A Lovely Day Bill Withers Vocal A Song for Mama Boyz II Men Vocal A Whole New World Disney Vocal Addicted to Love Robert Palmer Vocal All I Do Stevie Wonder Piano (WT) All of Me John Legend Vocal/Piano Anniversary Tony Toni Tone Vocal Ask of You Raphael Saadiq Vocal Autumn in New York Tony Bennett Vocal Autumn Leaves Matt Monro Vocal Bad Case of Loving You Robert Palmer Vocal Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Vocal Beat It Michael Jackson Vocal Before I Let Go Frankie Beverly/Maze Vocal Billie Jean Michael Jackson Vocal Blueberry Hill Fats Domino Vocal Brick House Commodores Vocal Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Vocal Buffalo Soldier Bob Marley Vocal Can’t Help Falling in Love Elvis Presley Vocal Can’t Let Go Anthony Hamilton Vocal Careless Whisper George Michael Vocal Cause I Love You Lenny Williams Vocal Celebration Kool and the Gang Vocal Change the World Eric Clapton Vocal Cheek to Cheek Fred Astaire Vocal Circle of Life Disney/Elton John Vocal Close the Door Teddy Pendergrass Vocal Cold Sweat James Brown Vocal Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Vocal Creepin’ Luther Vandross Vocal Dat Dere Tony Bennett Vocal Distant Lover Marvin Gaye Vocal Don’t Stop Believing Journey Vocal Don’t Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Vocal Don’t You Know That Luther Vandross Vocal Early in the Morning Gap Band Vocal End of the Road Boyz II Men Vocal Every Breath You Take The Police Vocal Feelin’ on Ya Booty R. -

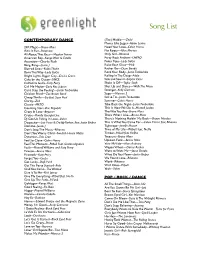

Greenlight's Complete Song List

Song List CONTEMPORARY DANCE (The) Middle—-Zedd Moves Like Jagger--Adam Levine 24K Magic—Bruno Mars Need Your Love--Calvin Harris Ain’t It Fun--Paramore No Roots—Alice Merton All About That Bass—Meghan Trainor Only Girl--Rihanna American Boy--Kanye West & Estelle Party Rock Anthem--LMFAO Attention—Charlie Puth Poker Face--Lady GaGa Bang, Bang—Jessie J Raise Your Glass—Pink Blurred Lines--Robin Thicke Rather Be—Clean Bandit Born This Way--Lady GaGa Rock Your Body--Justin Timberlake Bright Lights, Bigger City--Cee-Lo Green Rolling In The Deep--Adele Cake by the Ocean--DNCE Safe and Sound--Capitol Cities California Gurls--Katy Perry Shake It Off—Taylor Swift Call Me Maybe--Carly Rae Jepson Shut Up and Dance—Walk The Moon Can’t Stop the Feeling!—Justin Timberlake Stronger--Kelly Clarkson Chicken Fried—Zac Brown Band Sugar—Maroon 5 Cheap Thrills—Sia feat. Sean Paul Suit & Tie--Justin Timberlake Clarity--Zed Summer--Calvin Harris Classic--MKTO Take Back the Night--Justin Timberlake Counting Stars-One Republic This Is How We Do It--Montell Jordan Crazy In Love--Beyonce The Way You Are--Bruno Mars Cruise--Florida Georgia Line That’s What I Like—Bruno Mars DJ Got Us Falling In Love--Usher There’s Nothing Holdin’ Me Back—Shawn Mendes Despacito—Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee, feat. Justin Bieber This Is What You Came For—Calvin Harris feat. Rihanna Domino--Jessie J Tightrope--Janelle Monae Don’t Stop The Music--Rihanna Time of My Life—Pitbull feat. NeYo Don’t You Worry Child--Swedish House Mafia Timber--Pitbull feat. -

Roxbox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat

RoxBox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat. Thomas Jules & Bartender Jucxi D Blackout Careless Whisper Other Side 2 Unlimited 10 Years No Limit Actions & Motives 20 Fingers Beautiful Short Dick Man Drug Of Choice 21 Demands Fix Me Give Me A Minute Fix Me (Acoustic) 2Pac Shoot It Out Changes Through The Iris Dear Mama Wasteland How Do You Want It 10,000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Because The Night 2Pac Feat Dr. Dre Candy Everybody Wants California Love Like The Weather 2Pac Feat. Dr Dre More Than This California Love These Are The Days 2Pac Feat. Elton John Trouble Me Ghetto Gospel 101 Dalmations 2Pac Feat. Eminem Cruella De Vil One Day At A Time 10cc 2Pac Feat. Notorious B.I.G. Dreadlock Holiday Runnin' Good Morning Judge 3 Doors Down I'm Not In Love Away From The Sun The Things We Do For Love Be Like That Things We Do For Love Behind Those Eyes 112 Citizen Soldier Dance With Me Duck & Run Peaches & Cream Every Time You Go Right Here For You Here By Me U Already Know Here Without You 112 Feat. Ludacris It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Hot & Wet Kryptonite 112 Feat. Super Cat Landing In London Na Na Na Let Me Be Myself 12 Gauge Let Me Go Dunkie Butt Live For Today 12 Stones Loser Arms Of A Stranger Road I'm On Far Away When I'm Gone Shadows When You're Young We Are One 3 Of A Kind 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

All Audio Songs by Artist

ALL AUDIO SONGS BY ARTIST ARTIST TRACK NAME 1814 INSOMNIA 1814 MORNING STAR 1814 MY DEAR FRIEND 1814 LET JAH FIRE BURN 1814 4 UNUNINI 1814 JAH RYDEM 1814 GET UP 1814 LET MY PEOPLE GO 1814 JAH RASTAFARI 1814 WHAKAHONOHONO 1814 SHACKLED 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 20 FINGERS SHORT SHORT MAN 28 DAYS RIP IT UP 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 JAYS IN MY EYES 3 JAYS FEELING IT TOO 3 THE HARDWAY ITS ON 360 FT GOSSLING BOYS LIKE YOU 360 FT JOSH PYKE THROW IT AWAY 3OH!3 STARSTRUKK ALBUM VERSION 3OH!3 DOUBLE VISION 3OH!3 DONT TRUST ME 3OH!3 AND KESHA MY FIRST KISS 4 NON BLONDES OLD MR HEFFER 4 NON BLONDES TRAIN 4 NON BLONDES PLEASANTLY BLUE 4 NON BLONDES NO PLACE LIKE HOME 4 NON BLONDES DRIFTING 4 NON BLONDES CALLING ALL THE PEOPLE 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP 4 NON BLONDES SUPERFLY 4 NON BLONDES SPACEMAN 4 NON BLONDES MORPHINE AND CHOCOLATE 4 NON BLONDES DEAR MR PRESIDENT 48 MAY NERVOUS WRECK 48 MAY LEATHER AND TATTOOS 48 MAY INTO THE SUN 48 MAY BIGSHOCK 48 MAY HOME BY 2 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER GOOD GIRLS 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER EVERYTHING I DIDNT SAY 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER DONT STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER KISS ME KISS ME 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 50 CENT WINDOW SHOPPER 50 CENT IN DA CLUB 50 CENT JUST A LIL BIT 50 CENT 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT AND JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE AYO TECHNOLOGY 6400 CREW HUSTLERS REVENGE 98 DEGREES GIVE ME JUST ONE NIGHT A GREAT BIG WORLD FT CHRISTINA AGUILERA SAY SOMETHING A HA THE ALWAYS SHINES ON TV A HA THE LIVING DAYLIGHTS A LIGHTER SHADE OF BROWN ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON