6 X 10.Long New.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spencer Vicentini Sinclair

64 LGY#865 SPENCER VICENTINI SINCLAIR RATED T $3.99 US 0 6 4 1 1 7 5 9 6 0 6 0 8 9 3 6 9 BONUS DIGITAL EDITION – DETAILS INSIDE! PETER PARKER was bitten by a radioactive spider and gained the proportional speed, strength, and agility of a SPIDER, adhesive fingertips and toes, and the unique precognitive awareness of danger called “SPIDER-SENSE”! After the tragic death of his Uncle Ben, Peter understood that with great power there must also come great responsibility. He became the crimefighting super hero called… KING’S RANSOM Part Two Peter is rocking a new high-tech suit courtesy of Threats & Menaces. The suit allows TNM subscribers to watch the world through Spidey’s eyes, sending subscriptions through the roof. Spidey has been dealing with a spike in super-villain activity thanks to NYC mayor Wilson Fisk, the Kingpin, who’s seeking the pieces of the powerful Lifeline Tablet. Peter and his roommate, “reformed villain” Fred Myers, A.K.A. Boomerang, have been trying to keep the pieces out of Kingpin’s hands. So Kingpin assembled a cabal of villains to distract Spidey and Boomerang while he schemes behind the scenes with Baron Mordo! Meanwhile, Peter’s other roommate, Randy Robertson, rekindled his relationship with criminal Janice Lincoln, A.K.A. the Beetle-- which outraged their fathers, archenemies Robbie Robertson and Lonnie Lincoln, A.K.A. Tombstone. Madame Masque and the Crime Master ambushed Randy and Janice at Peter’s apartment and were holding them hostage when Peter and Fred returned. A fight ensued, and the apartment was blown open! NICK SPENCER ALEX SINCLAIR | colorist VC’s JOE CARAMAGNA | letterer writer MARK BAGLEY, JOHN DELL, and EDGAR DELGADO | cover artists CARLOS PACHECO, RAFAEL FONTERIZ, and RACHELLE ROSENBERG FEDERICO VICENTINI variant cover artists ANTHONY GAMBINO | designer LINDSEY COHICK | assistant editor artist NICK LOWE | editor C.B. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Resistant Vulnerability in the Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 2-15-2019 1:00 PM Resistant Vulnerability in The Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America Kristen Allison The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Susan Knabe The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Kristen Allison 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Allison, Kristen, "Resistant Vulnerability in The Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6086. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6086 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Established in 2008 with the release of Iron Man, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has become a ubiquitous transmedia sensation. Its uniquely interwoven narrative provides auspicious grounds for scholarly consideration. The franchise conscientiously presents larger-than-life superheroes as complex and incredibly emotional individuals who form profound interpersonal relationships with one another. This thesis explores Sarah Hagelin’s concept of resistant vulnerability, which she defines as a “shared human experience,” as it manifests in the substantial relationships that Steve Rogers (Captain America) cultivates throughout the Captain America narrative (11). This project focuses on Steve’s relationships with the following characters: Agent Peggy Carter, Natasha Romanoff (Black Widow), and Bucky Barnes (The Winter Soldier). -

The Only Way Is Down: Lark and Brubaker's Saga As '70S Cinematic

The Only Way is Down: Lark and Brubaker’s Saga as ’70s Cinematic Noir an Essay by Ryan K Lindsay from THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS: EXAMINING MATT MURDOCK AND DAREDEVIL THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS: EXAMINING MATT MURDOCK AND DAREDEVIL EDITED BY RYAN K. LINDSAY SEQUART RESEARCH & LITERACY ORGANIZATION EDWARDSVILLE, ILLINOIS The Devil is in the Details: Examining Matt Murdock and Daredevil Edited by Ryan K. Lindsay Copyright © 2013 by the respective authors. Daredevil and related characters are trademarks of Marvel Comics © 2013. First edition, February 2013, ISBN 978-0-5780-7373-6. All rights reserved. Except for brief excerpts used for review or scholarly purposes, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever, including electronic, without express consent of the publisher. Cover by Alice Lynch. Book design by Julian Darius. Interior art is © Marvel Comics; please visit marvel.com. Published by Sequart Research & Literacy Organization. Edited by Ryan K. Lindsay. Assistant edited by Hannah Means-Shannon. For more information about other titles in this series, visit sequart.org/books. The Only Way is Down: Lark and Brubaker’s Saga as ’70s Cinematic Noir by Ryan K Lindsay Cultural knowledge indicates that Daredevil is the noir character of the Marvel Universe. This assumption is an unchallenged perception that doesn’t actually hold much water under any major scrutiny. If you add up all of Daredevil’s issues to date, the vast majority are not “noir.” Mild examination exposes Daredevil as one of the most diverse characters who has ever been written across a series of genres, from swashbuckling romance, to absurd space opera, to straight up super-heroism and, often, to crime saga. -

Masculinity, Aging, Illness, and Death in Tombstone and Logan

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPER 791-51 DOI:10.5937/ ZRFFP48-18623 DANIJELA L J. P ETKOVIĆ1 UNIVERSITY OF N IŠ FACULTY OF P HILOSOPHY ENGLISH D EPARTMENT (IM)POSSIBLE MARTYRDOM: MASCULINITY, AGING, ILLNESS, AND DEATH IN TOMBSTONE AND LOGAN ABSTRACT. The title of this paper alludes to Hannah Arendt’s famous claim that in Nazi concentration camps martyrdom was made impossible, for the first time in Western history, by the utter anonymity and meaninglessness of inmates’ deaths (Arendt, 2000, p. 133): the paper, in contrast, examines two contem- porary films which, while intersecting normative/heroic masculinity with debilitating illness and death, allow for the possibility of martyrdom. Tomb- stone and Logan , directed by George P. Cosmatos and James Mangold respectively, depict the last days of such pop culture icons of masculinity as John Henry “Doc” Holliday and James Howlett, aka Logan/Wolverine. The films’ thematic focus on the (protracted) ending of life, which is evident not only in the storylines and dialogues but also in the numerous close-ups of emaciated, bleeding, scarred and prostrate male bodies, afflicted with tuberculosis and cancer-like adamantium poisoning, invites, first, a discus- sion of the relationship between the cinematic representations of normative and disabled masculinities. Specifically, since normative masculinity, as opposed to femininity, is synonymous with physical and mental strength, power and domination – including the control of one’s own body – the focus of this discussion is if, and how, the films depict Doc Holliday and Wolverine as feminized by their failing/disobedient bodies, thus contribut- ing to the cultural construction of gender. Secondly, the paper discusses the halo of martyrdom with which the films’ dying men are rewarded as emo- tionally deeply satisfying to the viewer: in Logan and Tombstone , death is not averted but hastened for the sake of friendship, family, and the protec- tion of the vulnerable and the marginalized. -

Avengers Dissemble! Transmedia Superhero Franchises and Cultic Management

Taylor 1 Avengers dissemble! Transmedia superhero franchises and cultic management Aaron Taylor, University of Lethbridge Abstract Through a case study of The Avengers (2012) and other recently adapted Marvel Entertainment properties, it will be demonstrated that the reimagined, rebooted and serialized intermedial text is fundamentally fan oriented: a deliberately structured and marketed invitation to certain niche audiences to engage in comparative activities. That is, its preferred spectators are often those opinionated and outspoken fan cultures whose familiarity with the texts is addressed and whose influence within a more dispersed film- going community is acknowledged, courted and potentially colonized. These superhero franchises – neither remakes nor adaptations in the familiar sense – are also paradigmatic byproducts of an adaptive management system that is possible through the appropriation of the economics of continuity and the co-option of online cultic networking. In short, blockbuster intermediality is not only indicative of the economics of post-literary adaptation, but it also exemplifies a corporate strategy that aims for the strategic co- option of potentially unruly niche audiences. Keywords Marvel Comics superheroes post-cinematic adaptations Taylor 2 fandom transmedia cult cinema It is possible to identify a number of recent corporate trends that represent a paradigmatic shift in Hollywood’s attitudes towards and manufacturing of big budget adaptations. These contemporary blockbusters exemplify the new industrial logic of transmedia franchises – serially produced films with a shared diegetic universe that can extend within and beyond the cinematic medium into correlated media texts. Consequently, the narrative comprehension of single entries within such franchises requires an increasing degree of media literacy or at least a residual awareness of the intended interrelations between correlated media products. -

THE PUNISHER WAR JOURNAL by Luis Filipe Based on Marvel Comics

THE PUNISHER THE PUNISHER WARWAR JOURNALJOURNAL by Luis Filipe Based on Marvel Comics character Copyright (c) 2017 This is just a fan made [email protected] OVER BLACK The sound of a POLICE RADIO calling. RADIO All units. Central Park shooting, requiring reinforcements immediately. CUT TO: CELL PHONE POV: Filming towards of Central Park alongside more people. Everyone horrified, but we don't know for what yet. CUT TO: VIDEO FOOTAGE: Now in Central Park where the police and CSI surround an entire area that is filled with CORPSES. A REPORTER talks to the camera. REPORTER Today New York witnessed the biggest outdoor massacre. It is speculated that the victims are members of the Mafia or even gangs, but no confirmation from the police yet. CUT TO: ANOTHER FOOTAGE: With the cameraman zooming in the forensic putting some bodies in black bags. One of them we notice that it's a little girl, and another a woman. REPORTER (O.S.) Apparently there was only one survivor. The victim is in serious condition but the paramedics doubt that he will hold it for long. CUT TO: SHAKY FOOTAGE: The only surviving man being taken on the stretcher to an ambulance. An oxygen mask on his face. His body covered in blood. He still uses his last forces to murmur. MAN My family... I want my... family. He is placed inside the ambulance. As the paramedics slam the ambulance doors - CUT TO BLACK: 2. Then - FADE IN: INT. CASTLE'S APARTMENT - DAY A small place with little furniture. The curtain blocks the sun from the single window of the apartment, allowing only a wispy sunlight to enter. -

Chapter Eleven an Angel in Tombstone 1880 – 1881

Baker/Toughnut Angel/11 1 Chapter Eleven An Angel in Tombstone 1880 – 1881 Tombstone, Arizona Territory, 1800s (Courtesy Tombstone Courthouse) Nellie stepped off the stage onto Allen Street’s dusty board sidewalk. She turned to catch her carpetbag when the stage driver lifted it down, but stumbled over the hem of her skirt into the path of a dark-haired man with a full mustache. The stranger grabbed Baker/Toughnut Angel/11 2 her waist. “Whoa. Welcome to Tombstone! Got your balance there, Ma’am?” Nellie pulled her traveling skirt out from under her button-down shoe and noticed the man wore a silver star on his blue shirt. He took her grip from the driver and set it on the sidewalk. “My name’s Virgil Earp.” Next to him two other men attempted not to laugh. Virgil smiled, and indicated the other two with his hand. “May I present my brother, Wyatt, and Doc Holliday?” Earp, not a common name. These must be the Earps who had served as lawmen in Dodge City. She’d read newspaper articles and one of T.J.’s dime novels about Wyatt Earp. Doc Holliday stopped stamping his black boots to remove the dust, bowed at the waist and swept his bowler hat from his head. He smelled of leather and, what was that? Sage? “Indeed, welcome to Tombstone, lovely lady.” He drawled in a bass voice from under another wide black mustache. That made Nellie think of how Papa had always joked that men with mustaches were trying to hide something -- their upper lips. -

SFU Thesis Template Files

“To Fight the Battles We Never Could”: The Militarization of Marvel’s Cinematic Superheroes by Brett Pardy B.A., The University of the Fraser Valley, 2013 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art, and Technology Brett Pardy 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2016 Approval Name: Brett Pardy Degree: Master of Arts Title: “To Fight the Battles We Never Could”: The Militarization of Marvel’s Cinematic Superheroes Examining Committee: Chair: Frederik Lesage Assistant Professor Zoë Druick Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Adel Iskander Supervisor Assistant Professor Michael Ma External Examiner Faculty Member Department of Criminology Kwantlen Polytechnic University Date Defended/Approved: June 16, 2016 ii Abstract The Marvel comics film adaptations have been some of the most successful Hollywood products of the post 9/11 period, bringing formerly obscure cultural texts into the mainstream. Through an analysis of the adaptation process of Marvel Entertainment’s superhero franchise from comics to film, I argue that a hegemonic American model of militarization has been used by Hollywood as a discursive formation with which to transform niche properties into mass market products. I consider the locations of narrative ambiguities in two key comics texts, The Ultimates (2002-2007) and The New Avengers (2005-2012), as well as in the film The Avengers (2012), and demonstrate the significant reorientation of the film franchise towards the American military’s “War on Terror”. While Marvel had attempted to produce film adaptations for decades, only under the new “militainment” discursive formation was it finally successful. -

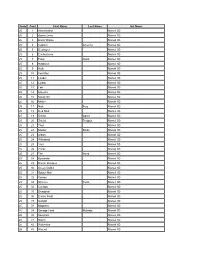

Form Card First Name Last Name Set Name 25 1 Abomination Marvel 3D

Form Card First Name Last Name Set Name 25 1 Abomination Marvel 3D 25 2 Baron Zemo Marvel 3D 25 3 Black Widow Marvel 3D 25 4 Captain America Marvel 3D 25 5 Destroyer Marvel 3D 25 6 Enchantress Marvel 3D 25 7 Frost Giant Marvel 3D 25 8 Hawkeye Marvel 3D 25 9 Hulk Marvel 3D 25 10 Iron Man Marvel 3D 25 11 Leader Marvel 3D 25 12 Lizard Marvel 3D 25 13 Loki Marvel 3D 25 14 Maestro Marvel 3D 25 15 Maria Hill Marvel 3D 25 16 Melter Marvel 3D 25 17 Nick Fury Marvel 3D 25 18 Red Skull Marvel 3D 25 19 Shield Agent Marvel 3D 25 20 Shield Trooper Marvel 3D 25 21 Thor Marvel 3D 25 22 Master Strike Marvel 3D 25 23 Ultron Marvel 3D 25 24 Whirlwind Marvel 3D 25 25 Ymir Marvel 3D 25 26 Zzzax Marvel 3D 25 27 The Hand Marvel 3D 25 28 Bystander Marvel 3D 25 29 Doctor Octopus Marvel 3D 25 30 Green Goblin Marvel 3D 25 31 Spider-Man Marvel 3D 25 32 Venom Marvel 3D 25 33 Scheme Twist Marvel 3D 25 34 Cyclops Marvel 3D 25 35 Deadpool Marvel 3D 25 36 Emma Frost Marvel 3D 25 37 Gambit Marvel 3D 25 38 Magneto Marvel 3D 25 39 Savage Land Mutates Marvel 3D 25 40 Sentinels Marvel 3D 25 41 Storm Marvel 3D 25 42 Wolverine Marvel 3D 25 43 Wound Marvel 3D 25 44 Egghead Marvel 3D 25 45 Daredevil Marvel 3D 25 46 Elektra Marvel 3D 25 47 Gladiator Marvel 3D 25 48 Punisher Marvel 3D 25 49 Blade Marvel 3D 25 50 Daredevil Marvel 3D 25 51 Elektra Marvel 3D 25 52 Ghost Rider Marvel 3D 25 53 Iron Fist Marvel 3D 25 54 Punisher Marvel 3D 25 55 Blade Marvel 3D 25 56 Daredevil Marvel 3D 25 57 Ghost Rider Marvel 3D 25 58 Iron Fist Marvel 3D 25 59 Punisher Marvel 3D 25 60 Electro Marvel -

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse

SPIDER-MAN: INTO THE SPIDER-VERSE Screenplay by Phil Lord and Rodney Rothman Story by Phil Lord Dec. 3, 2018 SEQ. 0100 - THE ALTERNATE SPIDER-MAN “TAS” WE BEGIN ON A COMIC. The cover asks WHO IS SPIDER-MAN? SPIDER-MAN (V.O.) Alright, let’s do this one last time. My name is Peter Parker. QUICK CUTS of a BLOND PETER PARKER Pulling down his mask...a name tag that reads “Peter Parker”...various shots of Spider-Man IN ACTION. SPIDER-MAN (V.O.) I was bitten by a radioactive spider and for ten years I’ve been the one and only Spider-Man. I’m pretty sure you know the rest. UNCLE BEN tells Peter: UNCLE BEN (V.O.) With great power comes great responsibility. Uncle Ben walks into the beyond. SPIDER-MAN (V.O.) I saved a bunch of people, fell in love, saved the city, and then I saved the city again and again and again... Spiderman saves the city, kisses MJ, saves the city some more. The shots evoke ICONIC SPIDER-MAN IMAGES, but each one is subtly different, somehow altered. SPIDER-MAN (V.O.) And uh... I did this. Cut to Spider-Man dancing on the street, exactly like in the movie Spider-Man 3. SPIDER-MAN (V.O.) We don’t really talk about this. A THREE PANEL SPLIT SCREEN: shots of Spider-Man’s “products”: SPIDER-MAN (V.O.) Look, I’m a comic book, I’m a cereal, did a Christmas album. I have an excellent theme song. (MORE) 2. SPIDER-MAN (V.O.) (CONT'D) And a so-so popsicle. -

Humans of New York: Managing Marvel's Spider-Man's Many Faces

(Super)Humans of New York: Managing Marvel's Spider-Man's Many Faces GDC March 2019 © 2019 Insomniac Games, Inc. Noah Alzayer Character TD © 2019 Insomniac Games, Inc. What’s Being Covered Process For Setting Up Working Relationship With a 3rd Party for Facial Rig Creation What’s Being Covered How We Added Our Own Twists After Delivery What’s Being Covered How We Tracked Changes We Made With Subsequent Iterative Deliveries What’s Being Covered Heads in the Open World Expectations A Living, Breathing New York. Expectations Very High Bar Expectations Character-Heavy Story Utilized a 3rd Party Extensive R&D and dedicated blendshape sculptors would be needed to do it all internally. Needed people who knew their stuff and had system in place. © 2018 3Lateral, All Rights Reserved 3Lateral Summary • Based on Photogrammetry Scanning • FACS Based GDC 2018 Tech Demos © 2018 3Lateral, All Rights Reserved FACS? “Facial Action Coding System (FACS) is a system to taxonomize human facial movements by their appearance on the face” © 2019 Insomniac Games, Inc. 3Lateral Summary • Based on Photogrammetry Scanning • Facial Action Coding System (FACS)- Based • Joint Deformation with Correctives • Blending Normal Maps and Color Maps for Wrinkles and Blood Flow • Custom Rig Logic Node Helps Speed • For More Info, See Their Many GDC Talks/YouTube GDC 2018 Tech Demos © 2018 3Lateral, All Rights Reserved Character Tiers © 2019 Insomniac Games, Inc. Character Tiers © 2019 Insomniac Games, Inc. Tier 1-3: “Named” Characters 21 Rigs Based On FACS Scans • DX11 shaders for Maya visualization • Tier 1: Peter, Tier 3: Tombstone • 257 joints • 400-600+ correctives for head mesh • 37 wrinkle and color tracks from 3 masked normal and 3 blood flow maps working in concert • Stan Lee Cameo © 2019 Insomniac Games, Inc.