On WJ Crawford's Studies of Physical Mediumship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British College of Psychic Science

Quarterly Transactions of the British College of Psychic Science. Vol. I.—No. 4. January, 1923. EDITORIAL NOTES. With the present issue, Psychic Science completes its first year, and the thanks of its sponsors are cordially extended to all those whose sympathetic support has carried the under taking so successfully through a difficult period. * * * * * The aim and scope of our “ Quarterly” is now, wetrust, sufficiently well defined. The aim is essentially a constructive one, whilst analytic in the quest of truth ; its scope catholic, disdaining no form of enquiry and investigation which may bear upon the many obscure problems of spiritual interaction with Matter and physical life, through all the tenebrous avenues of the psychic regions as yet untraversed by Mind. * * * * * We shall endeavour, in the year to come, to give further and clearer effect to these purposes and thereby to assist the College towards a more definite realization of its destined sphere of usefulness ; that it may bring to birth in vigorous form the embryonic idea now forming in the public mind of the University of Psychic Science that is to be. It is at least legitimate to hope that the College may be the incubator of such an idea, and a foster-mother until it be fully fledged. The pages of Psychic Science will be open to correspondence and suggestions towards this end. 304 Quarterly Transactions B.C.P.S. For this must surely come to pass, and in that day we look to see the ministers of religion and the professors of science working together with united aim, the “ tabu ” of religious bigotry, on the one hand, and of intellectual arrogance on the other, being laid aside, and a fraternal understanding established for the great work of re-edification now to be done in the rearing of a new Temple of Humanity, in which truth shall be worshipped and intolerance and super stition shall have no place. -

Doubles and Doubling in Tarchetti, Capuana, and De Marchi By

Uncanny Resemblances: Doubles and Doubling in Tarchetti, Capuana, and De Marchi by Christina A. Petraglia A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Italian) At the University of Wisconsin-Madison 2012 Date of oral examination: December 12, 2012 Oral examination committee: Professor Stefania Buccini, Italian Professor Ernesto Livorni (advisor), Italian Professor Grazia Menechella, Italian Professor Mario Ortiz-Robles, English Professor Patrick Rumble, Italian i Table of Contents Introduction – The (Super)natural Double in the Fantastic Fin de Siècle…………………….1 Chapter 1 – Fantastic Phantoms and Gothic Guys: Super-natural Doubles in Iginio Ugo Tarchetti’s Racconti fantastici e Fosca………………………………………………………35 Chapter 2 – Oneiric Others and Pathological (Dis)pleasures: Luigi Capuana’s Clinical Doubles in “Un caso di sonnambulismo,” “Il sogno di un musicista,” and Profumo……………………………………………………………………………………..117 Chapter 3 – “There’s someone in my head and it’s not me:” The Double Inside-out in Emilio De Marchi’s Early Novels…………………..……………………………………………...222 Conclusion – Three’s a Fantastic Crowd……………………...……………………………322 1 The (Super)natural Double in the Fantastic Fin de Siècle: The disintegration of the subject is most often underlined as a predominant trope in Italian literature of the Twentieth Century; the so-called “crisi del Novecento” surfaces in anthologies and literary histories in reference to writers such as Pascoli, D’Annunzio, Pirandello, and Svevo.1 The divided or multifarious identity stretches across the Twentieth Century from Luigi Pirandello’s unforgettable Mattia Pascal / Adriano Meis, to Ignazio Silone’s Pietro Spina / Paolo Spada, to Italo Calvino’s il visconte dimezzato; however, its precursor may be found decades before in such diverse representations of subject fissure and fusion as embodied in Iginio Ugo Tarchetti’s Giorgio, Luigi Capuana’s detective Van-Spengel, and Emilio De Marchi’s Marcello Marcelli. -

The Vital Message

The Vital Message By Arthur Conan Doyle Classic Literature Collection World Public Library.org Title: The Vital Message Author: Arthur Conan Doyle Language: English Subject: Fiction, Literature, Children's literature Publisher: World Public Library Association Copyright © 2008, All Rights Reserved Worldwide by World Public Library, www.WorldLibrary.net World Public Library The World Public Library, www.WorldLibrary.net is an effort to preserve and disseminate classic works of literature, serials, bibliographies, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and other reference works in a number of languages and countries around the world. Our mission is to serve the public, aid students and educators by providing public access to the world's most complete collection of electronic books on-line as well as offer a variety of services and resources that support and strengthen the instructional programs of education, elementary through post baccalaureate studies. This file was produced as part of the "eBook Campaign" to promote literacy, accessibility, and enhanced reading. Authors, publishers, libraries and technologists unite to expand reading with eBooks. Support online literacy by becoming a member of the World Public Library, http://www.WorldLibrary.net/Join.htm. Copyright © 2008, All Rights Reserved Worldwide by World Public Library, www.WorldLibrary.net www.worldlibrary.net *This eBook has certain copyright implications you should read.* This book is copyrighted by the World Public Library. With permission copies may be distributed so long as such copies (1) are for your or others personal use only, and (2) are not distributed or used commercially. Prohibited distribution includes any service that offers this file for download or commercial distribution in any form, (See complete disclaimer http://WorldLibrary.net/Copyrights.html). -

20 Chapter Source Notes

20. Saul Among The Prophets 1. pages 375-377. Atlantic City, New Jersey...finally contacted him. Our recreation was composited from several accounts including Harry Houdini, A Magician Among The Spirits (New York : Arno Press, 1972), 149-158; Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Edge Of The Unknown (New York : G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1930), 33-36; and “Editorial Notes” by Houdini, MUM, May, 1923, p.165. 2. page 379. Arthur Conan Doyle was born.... Details on Conan Doyle’s early life as it relates to spiritualism can be found in Kelvin I. Jones, Conan Doyle And The Spirits (England: The Aquarian Press, 1989) and Bernard M.L. Ernst and Hereward Carrington, Houdini And Conan Doyle (New York : Albert and Charles Boni, Inc., 1932). 3. page 379. “showed me at last…” Doyle 1887 letter to spiritualist journal Light, cited in “The Man Who Believed In Fairies”, by Tom Huntington, Smithsonian, clipping in the archives of James Randi. 4. page 379. Lord Kitchener... Kelvin I. Jones, Conan Doyle And The Spirits (England: The Aquarian Press, 1989), 110. 5. page 379. It was his book...knighthood in 1902. Ibid, 95. 6. page 379. revived him when...collaboration between the two men. “Conan Doyle’s Collaborator”, The Washington Post, April 10, 1902. 7. page 380. died after a long bout of tuberculosis... Kelvin I. Jones, Conan Doyle And The Spirits (England : The Aquarian Press, 1989), 100. 8. page 380. married Jean Leckie... Ibid. 9. page 380. Jean’s friend Lily Loder-Symonds... Ibid, 110-112. 10. page 380. “Where were they?…signals.” Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The New Revelation, 1917, 10-11. -

INDICE -.:: Biblioteca Virtual Espírita

INDICE A CIÊNCIA DO FUTURO......................................................................................................................................... 4 A CIÊNCIA E O ESPIRITISMO................................................................................................................................ 5 A PALAVRA DOS CIENTISTAS ..................................................................................................................... 6 UMA NOVA CIÊNCIA...................................................................................................................................... 7 O ESPIRITISMO ............................................................................................................................................. 8 O ESPIRITISMO E A METAPSÍQUICA........................................................................................................... 8 O ESPIRITISMO E PARAPSICOLOGIA ......................................................................................................... 9 A CIÊNCIA E O ESPÍRITO .................................................................................................................................... 10 A CIÊNCIA ESPÍRITA OU DO ESPÍRITO ............................................................................................................. 13 1. ALLAN KARDEC E A DEFINIÇÃO DO ESPIRITISMO, SOB O ASPECTO CIENTÍFICO......................... 14 2. A CIÊNCIA E SEUS MÉTODOS. ............................................................................................................. -

The Science of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2009 The cS ience of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival Benjamin R. Cox III [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Recommended Citation Cox, Benjamin R. III, "The cS ience of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival" (2009). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 31. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/31 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Science of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Benjamin R. Cox, III April, 2009 Mentor: Dr. J. Thomas Cook Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Winter Park, Florida This project is dedicated to Nathan Jablonski and Richard S. Smith Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 The Science of Mediumship.................................................................... 11 The Case of Leonora E. Piper ................................................................ 33 The Case of Eusapia Palladino............................................................... 45 My Personal Experience as a Seance Medium Specializing -

S.Macw / CV / NCAD

Susan MacWilliam Curriculum Vitae 1 / 8 http://www.susanmacwilliam.com/ Solo Exhibitions 2012 Out of this Worlds, Noxious Sector Projects, Seattle F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, Open Space, Victoria, BC 2010 F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, aceart inc, Winnipeg Supersense, Higher Bridges Gallery, Enniskillen Susan MacWilliam, Conner Contemporary, Washington DC F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, NCAD Gallery, Dublin 2009 Remote Viewing, 53rd Venice Biennale 2009, Solo exhibition representing Northern Ireland 13 Roland Gardens, Golden Thread Gallery Project Space, Belfast 2008 Eileen, Gimpel Fils, London Double Vision, Jack the Pelican Presents, New York 13 Roland Gardens, Video Screening, The Parapsychology Foundation Perspectives Lecture Series, Baruch College, City University, New York 2006 Dermo Optics, Likovni Salon, Celje, Slovenia 2006 Susan MacWilliam, Ard Bia Café, Galway 2004 Headbox, Temple Bar Gallery, Dublin 2003 On The Eye, Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast 2002 On The Eye, Butler Gallery, Kilkenny 2001 Susan MacWilliam, Gallery 1, Cornerhouse, Manchester 2000 The Persistence of Vision, Limerick City Gallery of Art, Limerick 1999 Experiment M, Context Gallery, Derry Faint, Old Museum Arts Centre, Belfast 1997 Curtains, Project Arts Centre, Dublin 1995 Liptych II, Crescent Arts Centre, Belfast 1994 Liptych, Harmony Hill Arts Centre, Lisburn List, Street Level Gallery, Irish News Building, Belfast Solo Screenings 2012 Some Ghosts, Dr William G Roll (1926-2012) Memorial, Rhine Research Center, Durham, NC. 2010 F-L-A-M-M-A-R-I-O-N, Sarah Meltzer Gallery, New York. -

HEREWARD CARRINGTON I Nia Cuurw Uakui I

I» HEREWARD CARRINGTON I nia cuurw UAKUi I o — L_: tj ^<!/0JllV3JO^ University Research Library s 8 8 U V t a K » £ « ft £ ft This book is DUE on the last date stamped below MOV 2 V:3A4 19^T MAY 1 3 *' " 1^ 1 3 ^^/ f©T IS 6 ^.^'A 0£C171961J '^fiK)V'^n'i^' UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA LIBRARY y , iA^ t*'^V^ <^ -A / s /\-f:- A BUUK ()}• fRorOlM) Sli.MIU.IXCI: PSYCHOTHERAPY By HUGO MUNSTERBERC^. M.D., PH.D., LITT.D., LL.D. Professor of Psycliology in Harvard i')iivc} sity 8t'o, $2.00 »('/. Hy iiuiil. $2.20. A maslerl\- discussion, wrillcn in simple un- technical language, of the Psychological IJasis of Psychotherapy, its Methods, Re- suits and Place in Civilization. It is the second hook in a series which Prof. Miin- sterherg is writing "to discuss for a wider public the practical applications of modern psychology." it deals with the relation of psychology to medicine. 1 the most "Undoubtedly important publij tion of the year."—Phila. Public Ledger.'. "On tlie whole, the best popular presentat| A the subject has ever had in English."—/:/7»(^ 1 can Journal of Psycliology. "Places for tlie first time the whole ma ler of the ni'W(.st and most wonder fvil o sciencess plainly, clearly and effecli\ely befnre an interested pul)lic."-—Minneapolis Trill II It I EUSAPIA PALLADINO AND HER PHENOMENA By HEREWARD CARRINGTON <^^-^-z^ Eusapia Palladino AND HER PHENOMENA BV HEREWARD CARRINGTON AUTHOR OF "the PHYBICAL phenomena of 8PIKITUALI8M," "VITALITT, FASTING AND NUTRITION," "the coming science," "HINDU MAGIC," ETC. -

Curriculum Vitae

1 Curriculum Vitae Christine Simmonds-Moore Contact information Melson hall room 215 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 678 839 5334 Education PGDip Consciousness Liverpool John Moore’s University 2009 and Transpersonal psychology PhD Psychology University of Northampton/University of Leicester 2003 Mphil Cognitive Science University of Dundee 1999 BA (Hons) Psychology University of Wales, Swansea 1993 Employment 2011 Assistant professor of University of West Georgia psychology 2010-2011 Visiting Assistant University of Virgina Professor of Psychiatry 2010-2011 Senior Research Fellow Rhine Research Center, Durham, NC 2001-2010 Senior Lecturer in Liverpool Hope University, Liverpool, UK Psychology 1998-2001 Part time Lecturer in University of Northampton/University of Psychology Leicester 1995-1997 Teaching Assistant University of Wales, Bangor, Wales, UK. 1994 Research Associate General Practice Research Unit, Gorseinon, (Health Psychology) Wales, UK (affiliated with Cardiff University) Classes taught at UWG Parapsychology PSYCH 4200 Parapsychology PSYCH 5200 2 Research Interests Altered states of consciousness, in particular those related to sleep; synaesthesia and consciousness, mental health and the personality dimension schizotypy (and related measures), the psychology of anomalous and paranormal experiences; the psychology of paranormal belief and disbelief; transpersonal psychology. Publications Holt, N., Simmonds-Moore, C., Luke, D. & French, C. (in press). Anomalistic Psychology (Palgrave Insights in Psychology series). Palgrave MacMillan. Simmonds-Moore, C.A. (in press). Overview and exploration of the state of play regarding health and exceptional experiences. Chapter to appear in C. Simmonds-Moore (Ed.). Exceptional experience and health: Essays on mind, body and human potential. Jefferson, NC: McFarland Press. Simmonds-Moore, C.A. (in press). Exploring ways of manipulating anomalous experiences for mental health and transcendence. -

Psypioneer Journals

PSYPIONEER F JOURNAL Edited by Founded by Leslie Price Archived by Paul J. Gaunt Garth Willey EST Amalgamation of Societies Volume 9, No. —12:~§~— December 2013 —~§~— 354 – 1944- Mrs Duncan Criticised by Spiritualists – Compiled by Leslie Price 360 – Correction- Mrs Duncan and Mrs Dundas 361 – The Major Mowbray Mystery – Leslie Price 363 – The Spiritualist Community Again – Light 364 – The Golden Years of the Spiritualist Association – Geoffrey Murray 365 – Continued – “One Hundred Years of Spiritualism” – Roy Stemman 367 – The Human Double – Psychic Science 370 – Five Experiments with Miss Kate Goligher by Mr. S. G. Donaldson 377 – The Confession of Dr Crawford – Leslie Price 380 – Emma Hardinge Britten, Beethoven, and the Spirit Photographer William H Mumler – Emma Hardinge Britten 386 – Leslie’s seasonal Quiz 387 – Some books we have reviewed 388 – How to obtain this Journal by email ============================= Psypioneer would like to extend its best wishes to all its readers and contributors for the festive season and the coming New Year 353 1944 - MRS DUNCAN CRITICISED BY SPIRITUALISTS The prosecution of Mrs Duncan aroused general Spiritualist anger. But an editorial in the monthly LIGHT, published by the London Spiritualist Alliance, and edited by H.J.D. Murton, struck a very discordant note:1 The Case of Mrs. Duncan AT the Old Bailey, on Friday, March 31st, after a trial lasting seven days, Mrs. Helen Duncan, with three others, was convicted of conspiring to contravene Section 4 of the Witchcraft Act of 1735, and of pretending to exercise conjuration. There were also other charges of causing money to be paid by false pretences and creating a public mischief, but after finding the defendants guilty of the conspiracy the jury were discharged from giving verdicts on the other counts. -

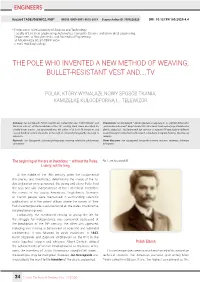

The Pole Who Invented a New Method of Weaving, Bullet-Resistant Vest And....Tv

ENGINEERS Ryszard TADEUSIEWICZ, PhD* ORCID: 0000-0001-9675-5819 Scopus Author ID: 7003526620 DOI: 10.15199/180.2020.4.4 * Professor in AGH University of Science and Technology, Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Automatics, Computer Science and Biomedical Engineering, Department of Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering al. Mickiewicza 30, 30-059 Kraków e-mail: [email protected] THE POLE WHO INVENTED A NEW METHOD OF WEAVING, BULLET-RESISTANT VEST AND....TV POLAK, KTÓRY WYNALAZŁ NOWY SPOSÓB TKANIA, KAMIZELKĘ KULOODPORNĄ I... TELEWIZOR Summary: Jan Szczepanik, Polish inventor was called, inter alia, “Polish Edison”, and Streszczenie: Jan Szczepanik – polski wynalazca, nazywany m. in. „polskim Edisonem”, “Austrian Edison”. At the breakdown of the 19th century, Mark Twain described his „austriackim Edisonem”. Na przełomie XIX i XX w. Mark Twain opisał jego działalność w activity in two papers. Jan Szczepanik was the author of at least 50 inventions and dwóch artykułach. Jan Szczepanik był autorem co najmniej 50 wynalazków i kilkuset several hundred technical patents in the field of coloured photography, weaving or opatentowanych pomysłów technicznych z dziedziny fotografii barwnej, tkactwa czy television. telewizji. Keywords: Jan Szczepanik, coloured photography, weaving, television, photometer, Słowa kluczowe: Jan Szczepanik, fotografia barwna, tkactwo, telewizja, fotometr, colorimeter kolorymetr The beginning of the era of inventions – without the Poles. Fig. 1. Jan Szczepanik [6] Luckily, not for long At the middle of the 19th century, when the fundamental discoveries and inventories, determining the shape of the to- day civilization were generated, the young and clever Poles had the only one aim: independence of the Fatherland. Therefore, the names of the young Americans, Englishmen, Germans or French people were memorized in outstanding scientific publications or in the patent offices where the names of their Polish contemporaries could be found on the plates, marking the insurrectionary graves. -

Dissociation and the Unconscious Mind: Nineteenth-Century Perspectives on Mediumship

Journal of Scientifi c Exploration, Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 537–596, 2020 0892-3310/20 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Dissociation and the Unconscious Mind: Nineteenth-Century Perspectives on Mediumship C!"#$% S. A#&!"!'$ Parapsychology Foundation [email protected] Submitted December 18, 2019; Accepted March 21, 2020; Published September 15, 2020 https://doi.org/10.31275/20201735 Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC Abstract—There is a long history of discussions of mediumship as related to dissociation and the unconscious mind during the nineteenth century. A! er an overview of relevant ideas and observations from the mesmeric, hypnosis, and spiritualistic literatures, I focus on the writings of Jules Baillarger, Alfred Binet, Paul Blocq, Théodore Flournoy, Jules Héricourt, William James, Pierre Janet, Ambroise August Liébeault, Frederic W. H. Myers, Julian Ochorowicz, Charles Richet, Hippolyte Taine, Paul Tascher, and Edouard von Hartmann. While some of their ideas reduced mediumship solely to intra-psychic processes, others considered as well veridical phenomena. The speculations of these individuals, involving personation, and di" erent memory states, were part of a general interest in the unconscious mind, and in automatisms, hysteria, and hypnosis during the period in question. Similar ideas continued into the twentieth century. Keywords: mediumship; dissociation; secondary personalities; Frederic W. H. Myers; Théodore Flournoy; Pierre Janet INTRODUCTION Dissociation, a process involving the disconnection of a sense of identity, physical sensations, and memory from conscious experience, has been related to mediumship due to the latter’s sensory and motor automatism and changes of identity. In recent years there have been some conceptual discussions of dissociation and mediumship (e.g., Maraldi et al., 2019) as well as empirical studies exploring their 538 Carlos S.