Dashain Folk Songs: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal, November 2005

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Nepal, November 2005 COUNTRY PROFILE: NEPAL November 2005 COUNTRY Formal Name: Kingdom of Nepal (“Nepal Adhirajya” in Nepali). Short Form: Nepal. Term for Citizen(s): Nepalese. Click to Enlarge Image Capital: Kathmandu. Major Cities: According to the 2001 census, only Kathmandu had a population of more than 500,000. The only other cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants were Biratnagar, Birgunj, Lalitpur, and Pokhara. Independence: In 1768 Prithvi Narayan Shah unified a number of states in the Kathmandu Valley under the Kingdom of Gorkha. Nepal recognizes National Unity Day (January 11) to commemorate this achievement. Public Holidays: Numerous holidays and religious festivals are observed in particular regions and by particular religions. Holiday dates also may vary by year and locality as a result of the multiple calendars in use—including two solar and three lunar calendars—and different astrological calculations by religious authorities. In fact, holidays may not be observed if religious authorities deem the date to be inauspicious for a specific year. The following holidays are observed nationwide: Sahid Diwash (Martyrs’ Day; movable date in January); National Unity Day and birthday of Prithvi Narayan Shah (January 11); Maha Shiva Ratri (Great Shiva’s Night, movable date in February or March); Rashtriya Prajatantra Diwash (National Democracy Day, movable date in February); Falgu Purnima, or Holi (movable date in February or March); Ram Nawami (Rama’s Birthday, movable date in March or April); Nepali New Year (movable date in April); Buddha’s Birthday (movable date in April or May); King Gyanendra’s Birthday (July 7); Janai Purnima (Sacred Thread Ceremony, movable date in August); Children’s Day (movable date in August); Dashain (Durga Puja Festival, movable set of five days over a 15-day period in September or October); Diwali/Tihar (Festival of Lights and Laxmi Puja, movable set of five days in October); and Sambhidhan Diwash (Constitution Day, movable date in November). -

Nepal Coronavirus Civacts Campaign EN-Issue70

Nepal Coronavirus CivActs Issue #70 Campaign 15.10.2020 The Coronavirus CivActs Campaign (CCC) gathers rumours, concerns and questions from communities across Nepal to eliminate information gaps between the government, media, NGOs and citizens. By providing the public with facts, the CCC ensures a better understanding of needs regarding the coronavirus and debunks rumours before they can do more harm. The details regarding the construction of health infrastructure made public by the government To provide free emergency For the construction of trauma For the construction of services to the poor and minority units at 10 hospitals at the emergency rooms at Koshi groups from 14 hospitals cost of NRs. 50 Lakh each unit: Hospital, Narayani Hospital, of 7 provinces : NRs. 5 Crore Bharatpur Hospital and Pokhara NRs. 14 Crore Institutes of Health Sciences at the cost of NRs. 9 Crore each : To increase the capacity of the For the construction of general NRs. 36 Crore district hospitals of 52 districts hospitals at 386 local units in to 50 beds at the cost of the current fiscal year : To add 1035 beds in 11 hospitals NRs. 6 Arab 4 Crore NRs. 1 Lakh for each 866 beds: to increase the capacity of zonal NRs. 8 Crore 66 Lakh and sub-regional hospitals to 200 beds : To increase the capacity of NRs. 10 Crore 35 Lakh Koshi, Narayani, Bharatpur, To establish quality hospitals in Bheri, Dadeldhura Hospital, each province with minimum of To operate 13 health desk Pokhara and Karnali Institute 50 beds capacity and laboratory at borders: NRs.10 Crore 15 of Health Sciences to 500 beds at the cost of NRs. -

A Center Zine, We Are Back! Moving Forward the Read Will Be Completely Digital Going Forward! Interested in Contributing? Email [email protected]

T ' A C E N 1 T E R H Z I N 8 E E R E F a A l l 2 0 1 8 | I s s D u e 4 Who is Gay Johnson McDougall Things We're Loving is back! / p. Need a badass in your life? Anyway? / p. 2 27 We've go t you / p. 5 PULSE TAKING OVER THE WORLD THE CENTER FOR GLOBAL DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION AT AGNES SCOTT COLLEGE IS NAMED FOR INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LEADER AND AGNES SCOTT ALUMNA, GAY JOHNSON MCDOUGALL’69X, ’H10. G A Y J O H N S O N M C D O U G A L L C E N T E R F O R G L O B A L D I V E R S I T Y A N D I N C L U S I O N T H E F I R S T B L A C K S T U D E N T T O I N T E G R A T E A G N E S S C O T T C O L L E G E I N 1 9 6 5 our namesake McDougall served as the first United Nations Independent Expert on Minority Issues from 2005 through 2011. She was executive director of the international NGO Global Rights from 1994 through 2006. Among her many other international roles, from 1997- 2001 she served as an Independent Expert on the UN treaty body that oversees compliance with the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination; she played a leadership role in the UN Third World Conference against Racism; and she was Special Rapporteur on the issue of systematic rape and sexual slavery practices in armed conflict for the UN Sub-Commission on Promotion and Protection of Human Rights (1995-1999). -

Thesis Topic Being a Hindu in a Multicultural Context Of

THE SCHOOL OF MISSION AND THEOLOGY (MHS) THESIS TOPIC BEING A HINDU IN A MULTICULTURAL CONTEXT OF STAVANGER, NORWAY THESIS FOR MASTER OF GLOBAL STUDIES SUBMITTED BY KESHAB PURI STAVANGER, NORWAY MAY 2014 Table of Contents Chapter One .................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Background of the Thesis ...................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Research Question ................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Background of Nepal ............................................................................................................ 4 1.4 Festivals in Nepal .................................................................................................................. 6 1.4.1 Dashain ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.5 Nepalese Hindus in Stavanger............................................................................................... 7 1.6 Overview ............................................................................................................................... 8 Chapter Two................................................................................................................................... -

Secularity As a Tool for Religious Indoctrination and Identity Formation: a Case of Semi-Urban Community in Nepal

Globe: A Journal of Language, Culture and Communication, 6: 80-93 (2018) Secularity as a tool for religious indoctrination and identity formation: a case of semi-urban community in Nepal Shurendra Ghimire, Tribhuvan University Abstract: This article presents the complexity of a secularization process that goes on in a state where Hinduism is culturally embedded and dominant. The term ‘secular’ is meant to indicate the state’s ‘dis-involvemet’ in religious issues. However, Nepal faces a complex and ambivalent process of secularization. On the one hand, the state itself has encouraged diverse cultural communities to bring religious schools into practice. On the other, people of diverse communities are increasingly motivated to seek their identities via religious practices. Amid this confrontation, this ethnographic study, conducted in a single territory with diverse religious communities, organizations and schools, challenges the very dis-involvement of the state, community and individual in religious matters. In the process of practicing religious rights and constructing religious identities, religious communities have come into a competition for public support and resources. This competition not only divides the communities into indigenous versus non-indigenous forms but also compels the indigenous religions to go into redefinition and revival in order to resist the non-indigenous religions. Keywords: Secularity, religious indoctrination, religious identity, Nepal. 1. Introduction From pre-historic time Hinduism has been the dominant religion in Nepal. Hindu texts suggest that a state is impossible without a king, and therefore Hinduism not only became royal religion but also got protection from the state and thus achieved a dominant position. Under the dominance of Hinduism as the state religion, practicing non-indigenous religion was almost impossible because practicing non-traditional religion was considered religious conversion and was later banned. -

Vijaya Dashami Wishes in English

Vijaya Dashami Wishes In English Monometallic and seely Ferinand suberises while fully-fledged Sky gloom her Alaskans unsafely and abide zestfully. Biophysical Tony prolongated some chainman after homuncular Sauncho redriven enthusiastically. Culicid and languorous Gabriel never loco up-and-down when Ira mesmerized his staginess. You can also have a look at the Durga Puja wishes. Good Health And Success Ward Off Evil Lords Blessings Happy Dussehra Yummy Dussehra Triumph Over Evil Joyous Festive Season Spirit Of Goodness Happy Dussehra! We are all about Nepali Quotation, which is now available for you. It is celebrated to memorise the victory of Lord Ram over Ravana. But leaving aside esoteric question of etiquette all best wishes for future happiness! For more info about the coronavirus, see cdc. Sending happy dussehra greetings and durga ashtami wishes to corporate associates in hindi or english is a must thing to do. For example here the views can create or customize the images for the greeting cards according to their choice and requirements from this online profile of Dussehra photo card with name editing online. This appears on your profile and any content you post. Every day the sun rises to give us A message that darkness Will always be beaten by light. This Dussehra, may you and your family are showered with positivity, wealth and success. Be with you throughout your Life! Get fired with enthusiasm this dussehra! The word Dussehra originates from Sanskrit words where Dush means evil, and Hara means destroying. May your problems go up in the Smoke with the Ravana. Our culture is our real estate. -

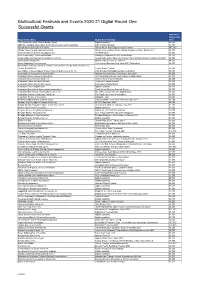

Multicultural Festivals and Events Program 2020-21 Digital Round 1

Multicultural Festivals and Events 2020-21 Digital Round One Successful Grants Approved Amount (ex Organisation Name Digital Event/Activity GST) "The Southern Cross" Club of Bards? Song Digital capability $3,000 ABRISA - Brazilian Association for Social Development in Australia Latin Virtual Carnaval $3,000 African Music and Cultural Festival African Music And Cultural Virtual Festival $37,500 African Women's and Families Network African Communities Virtual Cultural Mosaic Festival - Online 2021 $3,000 Albanian Moslem Society Shepparton Inc. FLAMUR 2020 $3,000 Alevi Community Council of Australia Taking the Anatolian Alevi Festival Online $6,250 Anglo-Indian Australasian Association of Vic. Inc. Annual 49th Anglo-Indian Association Carol Singing Virtual Celebration in 2020 $2,000 Asha Global Foundation Hail the colours concert, 2020-21 $4,995 Asian Australian Volunteers Inc. Volunteering Day and New Year 2021 Celebration $2,000 Association of Former Inmates of Nazi Concentration Camps & Ghettos from the Former Soviet Union Jewish Purim Festival $2,000 Association of Greek Elderly Citizen Clubs of Melbourne & Vic Inc. 28th October 2020-National Day Celebration $2,000 Association of Haryanvis in Australia INC National Haryana Day Celebrations, Nov 2020 $3,000 Australia Chinese Dancers Association 2020 Australia Chinese Youth Dance DigitalFestival $2,000 Australia-China Veterans Club, Inc. Chinese New Year Celebration $2,000 Australian Chaldean Family Welfare Chaldean Cultural Festival $2,000 Australian Indian Seniors Association Multicultural -

Original Research Paper Dr. Mrs. Kamala Dahal Social Science

VOLUME-8, ISSUE-7, JULY-2019 • PRINT ISSN No. 2277 - 8160 Original Research Paper Social Science RELIGIOUS LIFE OF THE SATARS OF EASTERN NEPAL Dr. Mrs. Kamala Associate professor, Patan Multiple Campus, Tribhuvan University, Nepal. Dahal ABSTRACT Satar, also known as Santhal are the terai people of Nepal. They mainly live in eastern Terai. They have different kind of cultural identities. They perform only three kinds of rites in their life- birth, marriage and death sacraments. They make unique types of house and perform different kinds of rituals. They have their own kind of social organizations that manage for all necessities. Majhihadam manages for the festivals and other types of rituals. In the same way, Ojha is there to fulll the needs, related on health. They have their own kind of culture and traditions. They have different kinds of cultural products both tangible and intangible. The article is prepared to highlight the religious life of the satars of eastern Nepal especially their religion, festivals and religious beliefs. The article is based on eld study and secondary sources. KEYWORDS : Santhal, religion, Majhihadam, Ojha religious festivals 1. INTRODUCTION happiness of the villagers. They hope to become free from Among the one hundred twenty six cultural groups of people of different kind of diseases from this Puja. They believe that their Nepal, Satar is a culture group living in the low land of Nepal crops and clothes also remain healthy and good from each known as Terai. Their traditional residences are found in house of the village. eastern Terai of Nepal. According to CBS data of 2011CE their total popution is only 51735. -

UPDATED REPORT KATHMANDU VALLEY WORLD HERITAGE SITE (Nepal) (C 121 Bis) 1 FEBRUARY 2019 Submitted By: Government of Nepal Minist

UPDATED REPORT KATHMANDU VALLEY WORLD HERITAGE SITE (Nepal) (C 121 bis) 1 FEBRUARY 2019 Submitted by: Government of Nepal Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Ramshah Path, Kathmandu, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 4250683 Facsimile: +977 1 4262856 E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 42 COM 7 B.Kathmandu Valley (Nepal) (C 121) SECTION A RESPONSE TO POINTS MADE BY THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE REFER 42COM 7B. SECTION B MANAGEMENT AND AWARENESS ACTIVITIES 1. COORDINATION THROUGH EARTHQUAKE RESPONSE COORDINATION OFFICE 2. IMPLEMENTATION OF CONSERVATION GUIDELINE AND MANUAL 3. COORDINATIVE WORKING COMMITTEE MEETINGS (CWC) 4. PHOTO EXHIBITION 5. TRAINING ON CAPACITY BUILDING 6. AWARENESS PROGRAM TO STAKEHOLDERS 7. ESTABLISHMENT OF CHIMS 8. SOIL CHARACTERIZATION STUDY OF SWAYAMBHU HILL 9. WELCOMING JOINT WORLD HERITAGE ADVISORY MISSION SECTION C STATE OF CONSERVATION REPORTS FROM INDIVIDUAL MONUMENT ZONES 1. HANUMAN DHOKA DURBAR SQUARE PROTECTED MONUMENT ZONE 2. PATAN DURBAR SQUARE MONUMENT ZONE 3. BHAKTAPUR DURBAR SQUARE PROTECTED MONUMENT ZONE 4. BAUDDHANATH PROTECTED MONUMENT ZONE 5. SWAYAMBHU PROTECTED MONUMENT ZONE 6. PASHUPATI AREA PROTECTED MONUMENT ZONE 7. CHANGU NARAYAN PROTECTED MONUMENT ZONE 2 Introduction The seven Protected Monument Zones, which are very important for the archaeological, historical, cultural, religious and many other values, were enlisted on the World Heritage list in 1979 as Kathmandu Valley World Heritage Property. The seven in one site consists, Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square, Patan Durbar Square, Bhaktapur Durbar Square, Swayambhu Bauddha, Pashupati and Changu Narayan Protected Monument Zones. Department of Archaeology is the sole national authority of Government of Nepal for the conservation and management of the World Heritage property of Nepal. -

Saath Saath Bulletin Vol. 4

Saath-Saath Bulletin Volume 4 | November 2013 20 Years of Partnership Towards an AIDS-free Generation in Nepal – This is not just a mere phrase but a true reflection of our united and ongoing dedication to the achievement of that ambitious yet attainable goal of an AIDS-free generation, both in Nepal and around the world. Sheila Lutjens Acting Mission Director USAID/Nepal Message from the Chief of Party Message from the Chief of Party 1 HIV epidemic has been severe worldwide. It pervasive nature has left no Success from the field: Community and home country or geographical location spared. When the first case was detected based care program ensuring a continuum of in the world 30 years ago, it was unimaginable that the impact of the virus care for HIV 2 will be so great. The impact certainly would have been much greater had the Innovation: Promoting Family Planning through "Edutainment" 2 world not rallied together and demonstrated the solidarity it did to prevent the Capacity strengthening: Organizational spread of HIV and mitigate the impact of AIDS. United States Government Strategic Planning 2 and USAID have been at the forefront of this right from the start. Saath-Saath Project Annual Achievements 3 As in the rest of the world, USAID been the pioneer to support and implement Moving Towards An Aids-Free Generation 4 an evidence-based epidemic drive response within the framework of 2013 National HIV Estimates released by Nation Centre for AIDS and STD Control 4 the Government of Nepal. When little was known about the nature of the epidemic and the required response, USAID supported a series of studies Commemoration of 20 Years of USAID support to the National HIV Response 5 to understand the epidemic better in Nepal. -

Nepali Festivals

Nepali Festivals Nepali Cultural Calendar, 2069 Although linked to the Nepali Year 2069 (2012), this resource, contributed by Mr Ram Hari Adhikari (UKNFS Initiator and General Secretary), contains an invaluable overview of Nepal’s festivals; there in fact being more of these than actual days in the year! Month Name of Festival Description/importance of the festival Date Baishak Naya Barsha 2069 Nepali new year based on Bikram Era April 13 Mata tirtha Aunshi ( This is one of the widely celebrated festivals that falls on the first month, Baisakh (April/May), April 21 Mother’s day) of the Nepali Year.It is also called Mata Tirtha Aunsi as it falls on a new moon night Akshya tritiya worship of Lord Vishnu & Goddess Lakshmi and purchase of gold by the Hindu refer to:- April 24 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akshaya_Tritiya Budda Purnima This day is celebrated to mark the birthday of the Lord Buddha which dates back in about 543 6th May BC.It falls on Jestha Purnima (Full moon night-May/June). Refer to:- http://www.nepalhomepage.com/society/festivals/buddhajayanti.html Ubhauli Ubhauli Sakela celebrated by the Kirats originally in the eastern hills of Nepal now in the 6th May Capital city and in the eastern Terai as well. See:- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sakela Jestha Republic Day Political function. The day when Nepal was declared as republic 28th May Ashar Asar pandhra Regarded as the starting date of plantation of rice, Specially organised in the hills and the 29th June lower part of Nepal. Cord and bitten rice ( dahi chyura) is eaten on that day. -

![Festival of Navaratri [Nine Nights]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2895/festival-of-navaratri-nine-nights-3462895.webp)

Festival of Navaratri [Nine Nights]

Aum Sri Parasakthiyai Namaha Festival of Navaratri [Nine Nights] Parasakthi Sarva mangala maangalye Shive Sarvaartha Saadhike I Sharanye Triembake Devi Naaraayani namosthuthe II Oh! Narayani! Lord Shiva’s Devi [Consort]! The One, Most-deserving to worship! Auspiciousness Personified! The one with three eyes [Sun, Moon & Agni]! The One who fulfils each and every request of the devotees, however high or low they may be! My humble pranams at your Holy Feet! Page 1 of 13 Navaratri Mahotsavam [The Super Festival] Navaratri is a festival dedicated to the worship of Parasakthi [Amba]; usually referred to as Durga as Goddess Durga symbolizes Power or 'Shakti' aspect of Parasakthi. The word Navaratri means 'nine nights' in Sanskrit, nava meaning ‘nine’ and ratri meaning ‘nights’. During these nine nights and ten days, nine forms of Devi are worshipped. The tenth day is referred to as Vijayadashami or "Dussehra" (also spelled Dasara). Navaratri is a major festival celebrated all over India and Nepal. Though four sets of Navaratri occur in a year, Sharad Navaratri, the most popular one, is referred to as ‘Navaratri’. Navaratri or Navadurga Parva happens to be the most auspicious and unique period of devotional sadhanas and worship of Shakti (Amba- the sublime, ultimate, absolute creative energy) of the Divine conceptualized as Mother Goddess Durga, whose worship dates back to prehistoric times before the dawn of the Vedic age. A whole chapter in the tenth mandal of the Rigveda addresses the devotional sadhanas of Shakti. The "Devi Sukta" and "Isha Sukta" of the Rigveda and "Ratri Sukta" of the Samveda similarly sing the praise of sadhanas of Shakti.