N8 Cashel Bypass & N74 Link Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mooresfort Lattin Co. Tipperary Tel 062 55385 Fax 062 55483 E-Mail [email protected]

Mooresfort Lattin Co. Tipperary Tel 062 55385 Fax 062 55483 E-mail [email protected] For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT In respect of the expansion of a PIG FARM DEVELOPMENT for Tankerstown Pig & Farm Enterprises Ltd. at Tankerstown, Bansha, Co. Tipperary July 2012 EPA Export 01-08-2012:00:11:50 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT In respect of the expansion of a PIG FARM DEVELOPMENT for Tankerstown Pig & Farm Enterprises Ltd. at Tankerstown, Bansha, Co. Tipperary For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. Prepared by NRGE Ltd. Mooresfort, Lattin, Co. Tipperary Date: July 2012 NRGE Ltd. Page 1 EPA Export 01-08-2012:00:11:50 PROJECT TEAM MICHAEL McENIRY B.Eng CIWM NRGE Ltd., MOORESFORT, LATTIN, CO. TIPPERARY JER KEOHANE M.Sc MIEI GEOTECHNICAL & SERVICES LTD., CARLOW RTC, CO. CARLOW MICHAEL SWEENEY NRGE Ltd., MOORESFORT, LATTIN, CO. TIPPERARY JOHN McENIRY BEng. MIEI, MAIN ST. BALLYPOREEN, CO. TIPPERARY DERMOT LEAHY B.Agr. Sc NRGE Ltd., MOORESFORT, LATTIN, CO. TIPPERARY JONAS RONAN DOMONIC DELANEY & ASSOCIATES For inspectionUNIT purposes 3, only. HOWLEY COURT Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. ORANMORE Co GALWAY M.Sc AML Archaeology MERVIN RICHARDSON JETWASH Ltd. LARS BO ADAMSEN M.Sc ANIMAL HOUSE DESIGN CONSULTANT SKIOLS A/S, Saeby, DENMARK JULIANNE O BRIEN BSCM, PDip ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION, NRGE Ltd., MOORESFORT, LATTIN, CO TIPPERARY NRGE Ltd. Page 2 EPA Export 01-08-2012:00:11:50 Table of Contents 1. Non-Technical Summary 2. Introduction 2.1 Relevant Regulations for Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) 2.2 National and E.C. -

Ireland P a R T O N E

DRAFT M a r c h 2 0 1 4 REMARKABLE P L A C E S I N IRELAND P A R T O N E Must-see sites you may recognize... paired with lesser-known destinations you will want to visit by COREY TARATUTA host of the Irish Fireside Podcast Thanks for downloading! I hope you enjoy PART ONE of this digital journey around Ireland. Each page begins with one of the Emerald Isle’s most popular destinations which is then followed by several of my favorite, often-missed sites around the country. May it inspire your travels. Links to additional information are scattered throughout this book, look for BOLD text. www.IrishFireside.com Find out more about the © copyright Corey Taratuta 2014 photographers featured in this book on the photo credit page. You are welcome to share and give away this e-book. However, it may not be altered in any way. A very special thanks to all the friends, photographers, and members of the Irish Fireside community who helped make this e-book possible. All the information in this book is based on my personal experience or recommendations from people I trust. Through the years, some destinations in this book may have provided media discounts; however, this was not a factor in selecting content. Every effort has been made to provide accurate information; if you find details in need of updating, please email [email protected]. Places featured in PART ONE MAMORE GAP DUNLUCE GIANTS CAUSEWAY CASTLE INISHOWEN PENINSULA THE HOLESTONE DOWNPATRICK HEAD PARKES CASTLE CÉIDE FIELDS KILNASAGGART INSCRIBED STONE ACHILL ISLAND RATHCROGHAN SEVEN -

Intelligent Transportation Systems.Pdf

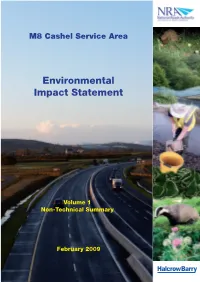

M8 Cashel Service Area Environmental Impact Statement Volume 1 Non-Technical Summary February 2009 National Roads Authority An tÚdarás um Bóithre Náisiúnta PROJECT: M8 Cashel Service Area DOCUMENT: Environmental Impact Statement Volume 1: Non Technical Summary DATE: February 2009 M8 Cashel Service Area EIS Volume 1 M8 Cashel Service Area EIS Volume 1 Preface The structure of the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the proposed M8 Cashel Service Area, is laid out in the preface of each volume for clarity. The document consists of the following four volumes: Volume 1 – Non Technical Summary A non technical summary of information contained in Volume 2 Volume 2 - Environmental Impact Statement This volume describes the environmental impact of the proposed development including the layout, structure, access / egress points and associated auxiliary works to the proposed developments. Volume 3 – Drawings A dedicated volume of drawings that further describe the information set out in Volume 2 Volume 4 – Technical Appendices Data that is supplemental to the information in Volume 2. M8 Cashel Service Area EIS Volume 1 M8 Cashel Service Area EIS Volume 1 Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 Consultation 2 2 Background to the Proposed Development 4 2.1 NRA Policy 4 2.2 Procurement Approach 4 2.3 Function of the Proposals on a National, Regional and Local Level 4 2.4 Existing Conditions 5 2.5 Alternatives Considered 5 3 Description of the Proposed Development 6 3.1 Introduction 6 3.2 Site Layout Principles 6 3.3 Roads and Parking 6 3.4 Service Area Building 7 3.5 Fuel Station Facilities. -

Inquiry Into the Derailment of a Freight Train at Cahir Viaduct on 7Th October 2003

Inquiry into the Derailment of a Freight Train at Cahir Viaduct on 7th October 2003 (Cover image courtesy of Radio Teilifís Éireann) Inquiry into Derailment at Cahir Viaduct on 7th October 2003 – Report (version 1.2) 22/12/2005 Contents Contents .............................................................................................................................. 3 Tables.................................................................................................................................. 4 Illustrations ......................................................................................................................... 5 Illustrations ......................................................................................................................... 5 1 Executive Summary:................................................................................................... 6 2 Referencing Convention: ............................................................................................ 8 3 The accident:............................................................................................................. 10 4 Background............................................................................................................... 12 4.1 The Railway:..................................................................................................... 12 4.2 The Site:............................................................................................................ 13 4.3 The Service: ..................................................................................................... -

South Tipperary Heritage Plan 2012-2016

South Tipperary Heritage Plan 2012-2016 “Heritage is not so much a thing of the past but of the present and the future.” — Michael Starrett Chief Executive, the Heritage Council South Tipperary Heritage Plan 2012-2016 TEXT COMPILED AND EDITED BY JANE-ANNE CLEARY, LABHAOISE MCKENNA, MIEKE MUYLLAERT AND BARRY O’REILLY IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE SOUTH TIPPERARY HERITAGE FORUM PRODUCED BY LABHAOISE MCKENNA, HERITAGE OFFICER, SOUTH TIPPERARY COUNTY COUNCIL © 2012 South Tipperary County Council This publication is available from: The Heritage Officer South Tipperary County Council County Hall, Clonmel, Co. Tipperary Phone: 052 6134650 Email: [email protected] Web: www.southtippheritage.ie All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission in writing of the publisher. Graphic Design by Connie Scanlon and print production by James Fraher, Bogfire www.bogfire.com This paper has been manufactured using special recycled fibres; the virgin fibres have come from sustainably managed forests; air emissions of sulphur, CO2 and water pollution have been limited during production. CAPTIONS INSIDE FRONT COVER AND SMALL TITLE PAGE: Medieval celebrations along Clonmel Town Wall during Festival Cluain Meala. Photograph by John Crowley FRONTISPIECE: Marlfield Church. Photograph by Danny Scully TITLE PAGE: Cashel horse taken on Holy Cross Road. Photograph by Brendan Fennessey INSIDE BACK COVER: Hot Horse shoeing at Channon’s Forge, Clonmel. Photograph by John D Kelly. BACK COVER: Medieval celebrations along Clonmel’s Town Wall as part of Festival Cluain Meala. -

Moycarkey Old Graveyard Headstone Inscriptions

Moycarkey Old Graveyard Headstone Inscriptions Three Monuments inside the Catholic church. 1 Beneath lie the remains / Of / Revd. John Burke /(native of Borris) / He was born 1809 Ordained priest 1839 / Appointed P P Moycarkey & Borris 1853 /Died 2nd August 1891 /R.I.P. / Erected by the people of Moycarkey. Stonecutter P.J. O'Neill & Co. Gr. Brunswick St, Dublin. 2 Beneath are deposited / The remains of the / Rev Patrick O'Grady /Of Graigue Moycarkey / Died on the English mission / At London /On the 17th of Jan 1887 / Aged 26 years / Erected by his loving father. Stonecutter. Bracken Templemore 3 Beneath / Are deposited the remains of /The Rev Robert Grace P.P. of /Moycarkey and Borris / Who departed this life the 2nd / Of Octr. 1852 / Aged 60 years /Requiescat in pace / Erected by Revd. Richd. Rafter. Stonecutter. J. Farrell Glasnevin. 1 Headstones on Catholic church grounds. 1 Erected by / William Max Esq / Of Maxfort / In memory of / His dearly beloved wife / Margaret / Who died 2nd Novr 1865 / Most excellent in every relation of life / A most devoted wife / And sterling friend / Also the above named / William Max Esq /Died 1st Feby 1867 aged 72 years / Deeply regretted by / A large circle of friends / R.I.P. 2 Very Rev Richard Ryan / Parish Priest / of / Moycarkey, Littleton and Two-Mile-Borris / 1986-2002 / Died 10th January 2002 / Also served God and God’s people / In / Raheny, Doon, Ballylanders / Thurles and Mullinahone / Requiescat in pace. 3 In memory of / Very Rev. Daniel M. Ryan / Born Ayle, Cappawhite November 26th 1915 / Ordained priest Maynooth June 22 1941 / Professor St Patricks College Carlow 1942 – 1947 / Professor St Patricks College Thurles 1947 – 1972 / Parish priest Moycarkey Borris 1972 – 1986 / Associate pastor Lisvernane December 1986 / Died feast of St Bridget February 1st 1987 / A Mhuire na nGael gui orainn. -

South Tipperary Senior Football Final Match Programme 1996 , Coiste Thiobrad Arann Theas

South Tipperary Senior Football Final Match Programme 1996 , Coiste Thiobrad Arann Theas peil Sinnsear An Cluichi Ceannais FANAITHE NA MAOILIG v NATRACTALI 3.15 P.M. Reiteoir: Liam 6 Bar6id i gCill Sioitiin 4 Lunasa 1996 Iomaint • CILL SIOLAIN v FIODHARD 2.00 p.m. Reiteo;r: A De Roiste MOYLAN & MURRAY MAIN ®TOYOTA DEALERS FOLL RANGE OF NEW TOYOTA VEHICLES EX-STOCK ATMOYlAN&MURRAY YOUUALWAYSGETA RESULT 1st for Soles -- 1st for Service -- 1st for ParIs TOYOTA~ j ~j • • USEOCAR WAIWMY UNUMITED lSWnS MUAGE PARTS & hi your sights high.r LABOUR Forecourt facilities from 7.30 a.m. /0 midnight Ca5110/ Road, Clonmo!. Co. Tipperary. To!,: 052·21177 Fax: 052·23035 Fergal, Tom and Staff delighted to be associated with L Local GAA ".J Failte on gCathaoirIeach ClIirin .fili/le 0 chroi gach ell/ine go ('ill Sio/ain innill al' an fa IIlO,. peif sco. Toitll einnlc go mheidh ana chillichi aguil1l1 sa Cllliche ('heal7lwis Sil7l1sear. Today's S'eniur Final is a repeal of lasf year's eIJcOllnler. Moyle Rovers were fhe victors un Ihal occasion and wenl 0/1 10 emu/ale COII/mercia/s feal of 199.1 by laking fhe ('Olll1ly Crown und contesting the Munster Club final. Commercials will he sfril'ing 10 turn fhe fahles on (heir more fancied opponents ami with players of crqji and experience could pose a serio liS challenge, ' Moyle Rovers, however, are !)laying wifh the confidence of champions and wiff 1101 relinquish their tille without a hattIe royal. Whatever the Oil/come a cracking contcs! is in pro.~pec! and a sali,~fi;lcfory conclusion to what has heen ajine championship. -

The Mcgrath Clonoulty Curragh Descent by Michael F

The McGrath Clonoulty Curragh Descent By Michael F. McGraw, Ph.D. [email protected] Revised: November 8, 2018 Introduction The first portion of this paper is based on information from the paper “Descendants of Philip McGrath,” provided to the author by Con Ryan of Dublin. Ryan’s paper was in the form of a short narrative and contained gravestone transcriptions and photos from Clonoulty Cemetery in the village of Clonoulty (Clonoulty Churchquarter townland). The second portion of this paper contains family trees constructed for these same families complimented with information from the Clonoulty parish registers, civil registrations, and census records. ★ Philip Magrath From Cemetery Inscriptions Of Clonoulty Curragh Philip Magrath = ? Thomas Magrath b. 1778 d. May 7, 1810 (Age 22) Denis Magrath = Hanora Hickey b. 1782 b. 1787 d. Feb. 1, 1857 d. March 1864 Patrick Magrath b. 1830 d. Aug 22, 1907 (age 77) James Magrath = Mary Dwyer b. 1796 d. Dec 28, 1833 Inscription from Clonoulty Cemetery 97. Here lies the body of Thomas / MaGrath / who depd life May 7th 1810 aged 22 years May he / rest in peace Amen Erectd / by his father Philip MaGrath of Clonoulty / Patrick Magrath died 22nd Aug 1907 / aged 77 vrs Also his mother Hanora / nee Hickey died March 1864 aged 77 yrs The names are highlighted to indicate the corresponding individuals in the inscriptions and family trees on the same page. The McGrath Clonoulty Curragh - 1 - Copyright © 2015-18 Michael F. McGraw, Ph.D. Descent 11-08-18a Table of Contents The McGrath Clonoulty Curragh Descent ................................................................................. 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 ★ Philip Magrath From Cemetery Inscriptions ........................................................................ -

Hide and Seek with Windows Shuttered and Corridors Empty for the First Six Months of the Year, Many Hotels Have Taken the Time to Re-Evaluate, Refresh and Rejuvenate

TRAVEL THE CLIFF AT LYONS Hide and Seek With windows shuttered and corridors empty for the first six months of the year, many hotels have taken the time to re-evaluate, refresh and rejuvenate. Jessie Collins picks just some of the most exciting new experiences to indulge in this summer. THE CLIFF AT LYONS What’s new Insider Tip Aimsir is upping its focus on its own garden produce, Cliff at Lyons guest rooms are all individually designed Best-loved for which is also to be used in the kitchens under the eye of and spread out between a selection of historic buildings Its laid-back luxurious feel and the fastest ever UK and former Aimsir chef de partie and now gardener, Tom that give you that taste of country life while maintaining Ireland two-star ranked Michelin restaurant, Aimsir. Downes, and his partner Stina. Over the summer, a new all the benefits of a luxury hotel. But there is also a There are award-winning spa treatments to be had at orchard will be introduced, along with a wild meadow selection of pet-friendly rooms if you fancy taking your The Well in the Garden, and with its gorgeous outdoor and additional vegetable beds which will be supplying pooch with you. Also don’t forget the Paddle and Picnic spaces, local history, canal walks, bike rides and paddle- the Cliff at Lyons restaurants. Chicken coops, pigs and package which gives you a one-night B&B stay plus SUP boarding there’s plenty to do. Sean Smith’s fresh take even beehives are also to be added, with the aim of session, and a picnic from their pantry, from €245 for two on classic Irish cuisine in The Mill has been a great bringing the Cliff at Lyons closer to self-sustainability. -

Management Report to Council

Management Report to Council O COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT & TOURISM O WATER SERVICES O ENVIRONMENT & LAWCO O HOUSING O CORPORATE SERVICES /HUMAN RESOURCES December 2018 1 | Page COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DIRECTORATE Enterprise & Economic Development & Tourism – Group A Economic Development Action Area Update Local Economic & Meeting of LECP Advisory Group was held in July to review progress of the Community Plan 2018 Economic Action Plan. A three year LECP progress report and Draft (LECP) 2015 -2020 2019 Economic Action Plan will also be presented at this meeting. Retail-Commercial Attracted 13 applications in the current year across all 5 MD’s. The Incentive Scheme information portal at www.tipperarycoco.ie/cis is the first point of contact for the scheme. Payments being made to grantees under the 2018 grant scheme. Retail Town Centre Retail Forums are currently in operation in 6 of the 9 towns and are actively Initiative supported by the Municipal Districts. Various activities are being undertaken including running of festivals; marketing initiatives, town regeneration initiatives and surveys. A marketing effort/ shop local campaign was developed to promote more local shopping including a logo, social media channels and an online marketing campaign. Thus campaign will begin again in the run up to Christmas to promote ‘Shop Local’ The Christmas Retail Support Grant Scheme was recently advertised in all local media with details circulated to stakeholders and previous beneficiaries. The 2018 scheme attracted 31 Applications. Grant offers will issue in the coming week to all successful applicants. Digital Media/Gaming BuzzQuarter: Tipperary’s seat ready digital studio is now open at Questum, Corridor Clonmel. -

Train YOUR PRIVATE ISLAND

train YOUR PRIVATE ISLAND ‘We could not have asked for better than the outstanding facilities of Fota Island Resort for our pre UEFA EURO 2016 training camp, and during our more recent visit to Cork. All the essential requirements for a high quality training camp are on site and we have been thoroughly impressed during our stays here.’ Martin O’Neill, Ireland Senior Men’s Football Manager Fota Island Resort As a five star resort you will find excellent comfort, convenience and security for your team. Teams can stay onsite for the entire duration of the stay as we provide all the facilities needed. The training pitch and team gym are walking distance from the accommodation options, which range from spacious hotel rooms to luxurious self-catering lodges. There are team meeting rooms, dining rooms, physio rooms and kit rooms available, as well as varied running trails around the resort. There is complimentary Wi-Fi throughout the resort and ample private carparks. “May I extend our sincere thanks to you for the fantastic assistance that you offered our group in the planning of and during the course of our stay at Fota Island Resort last week; it was a most productive and enjoyable training camp with a perfect mix of work and play – great facility.” Kieran McCarthy, Rugby Chairman, London Irish RFC “Thank you to you and all the team for looking after us so well for the 2 days. Everything was really great but as ever it is the staff that really make the difference so thanks again to all.” Kilkenny Hurling Team Training Facility The main attraction of the excellent training facility here is the pristine playing area, which is 155m x 130m. -

Report to Inform Screenings for Appropriate Assessment

Report to inform Screening for Appropriate Assessment Glanmire Road Improvements and Sustainable Transport Works, Co. Cork Project Number: 60559532 3 May 2018 Revision 4 Report to Inform Screening for Appropriate Assessment Quality information Prepared by Checked by Approved by Robert Fennelly Dr Miles Newman Dr Eleanor Ballard Principal Ecologist Consultant Ecologist Associate Director (of Ecology) Revision History Revision Revision date Details Authorized Name Position Rev0 27 Feb 2018 Draft issue for CCC Yes Robert Fennelly Principal Ecologist comment Rev1 13 Mar 2018 Minor changes to Yes Robert Fennelly Principal Ecologist address client comments Rev2 13 April 2018 Revised for Cork Yes Robert Fennelly Principal Ecologist County Council comments; version for planning purposes Rev3 26 April 2018 Revised for Yes Robert Fennelly Principal Ecologist drainage input statement Rev4 03 May 2018 Minor revisions Yes Robert Fennelly Principal Ecologist prior to planning issue Distribution List # Hard Copies PDF Required Association / Company Name Prepared for: AECOM Report to Inform Screening for Appropriate Assessment Prepared for: Prepared for: Cork County Council Prepared by: AECOM Ireland Limited 1st Floor, Montrose House Douglas Business Centre Carrigaline Road Douglas, Co. Cork T12H90H T +353-(0)21-436-5006 aecom.com © 2018 AECOM Ireland Limited. All Rights Reserved. This document has been prepared by AECOM Ireland Limited (“AECOM”) for sole use of our client (the “Client”) in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document.