NPS Form 10 900-B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Building & Grounds Maintenance Event Staff Job Posting

2021 Building & Grounds Maintenance Event Staff Job Posting Roger Williams Park Zoo (RWPZ) of Providence, Rhode Island, is one of the nation’s oldest zoos, exhibiting over 100 animal species. Our culture is built on our core values -community, fun, innovation, diversity, integrity, sustainability, and excellence. We value our role in the community as a treasured place for families and a trusted resource for learning; we create a sense of community for our staff and contribute to the global conservation community. We provide a fun experience for our guests and believe that a fun environment is essential to create a great workplace. We are willing to take risks, to propose novel ideas and to think “out of the box”. Bold dreams are welcome here. We act with respect toward all. We value diversity and are intolerant of bias. Integrity and honesty drive our business practices and our relationships with each other and our constituents. We are driven by our vision of greater sustainability in our environmental practices and in our business model. We believe that by establishing a sustainable financial base we can best achieve our goals. We are always striving for excellence. We work to exceed expectations in all areas. We welcome all who share our core values! RWPZ is currently recruiting for part-time, Buildings & Grounds Maintenance Event Staff. The Buildings & Grounds Maintenance Staff are responsible for the custodial activities for Roger Williams Park Zoo and Carousel Village during events such as the Asian Lantern Spectacular, Zoobilee, Brew at the Zoo, Jack-O-Lantern Spectacular, Holiday lights as well as Food Truck Fridays and after-hour Zoo events. -

Tidal Flushing and Eddy Shedding in Mount Hope Bay and Narragansett Bay: an Application of FVCOM

Tidal Flushing and Eddy Shedding in Mount Hope Bay and Narragansett Bay: An Application of FVCOM Liuzhi Zhao, Changsheng Chen and Geoff Cowles The School for Marine Science and Technology University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth 706 South Rodney French Blvd., New Bedford, MA 02744. Corresponding author: Liuzhi Zhao, E-mail: [email protected] 1 Abstract The tidal motion in Mt. Hope Bay (MHB) and Narragansett Bay (NB) is simulated using the unstructured grid, finite-volume coastal ocean model (FVCOM). With an accurate geometric representation of irregular coastlines and islands and sufficiently high horizontal resolution in narrow channels, FVCOM provides an accurate simulation of the tidal wave in the bays and also resolves the strong tidal flushing processes in the narrow channels of MHB-NB. Eddy shedding is predicted on the lee side of these channels due to current separation during both flood and ebb tides. There is a significant interaction in the tidal flushing process between MHB-NB channel and MHB-Sakonnet River (SR) channel. As a result, the phase of water transport in the MHB-SR channel leads the MHB-NB channel by 90o. The residual flow field in the MHB and NB features multiple eddies formed around headlands, convex and concave coastline regions, islands, channel exits and river mouths. The formation of these eddies are mainly due to the current separation either at the tip of the coastlines or asymmetric tidal flushing in narrow channels or passages. Process-oriented modeling experiments show that horizontal resolution plays a critical role in resolving the asymmetric tidal flushing process through narrow passages. -

View Strategic Plan

SURGING TOWARD 2026 A STRATEGIC PLAN Strategic Plan / introduction • 1 One valley… One history… One environment… All powered by the Blackstone River watershed and so remarkably intact it became the Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor. SURGING TOWARD 2026 A STRATEGIC PLAN CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................ 2 Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor, Inc. (BHC), ................................................ 3 Our Portfolio is the Corridor ............................ 3 We Work With and Through Partners ................ 6 We Imagine the Possibilities .............................. 7 Surging Toward 2026 .............................................. 8 BHC’s Integrated Approach ................................ 8 Assessment: Strengths & Weaknesses, Challenges & Opportunities .............................. 8 The Vision ......................................................... 13 Strategies to Achieve the Vision ................... 14 Board of directorS Action Steps ................................................. 16 Michael d. cassidy, chair Appendices: richard gregory, Vice chair A. Timeline ........................................................ 18 Harry t. Whitin, Vice chair B. List of Planning Documents .......................... 20 todd Helwig, Secretary gary furtado, treasurer C. Comprehensive List of Strategies donna M. Williams, immediate Past chair from Committees ......................................... 20 Joseph Barbato robert Billington Justine Brewer Copyright -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

For the Conditionally Approved Lower Providence River Conditional Area E

State of Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management Office of Water Resources Conditional Area Management Plan (CAMP) for the Conditionally Approved Lower Providence River Conditional Area E May 2021 Table of Contents Table of Contents i List of Figures ii List of Tables ii Preface iii A. Understanding and Commitment to the Conditions by all Authorities 1 B. Providence River Conditional Area 3 1. General Description of the Growing Area 3 2. Size of GA16 10 3. Legal Description of Providence River (GA 16): 11 4. Growing Area Demarcation / Signage and Patrol 13 5. Pollution Sources 14 i. Waste Water Treatment Facilities (WWTF) 14 ii. Rain Events, Combined Sewer Overflows and Stormwater 15 C. Sanitary Survey 21 D. Predictable Pollution Events that cause Closure 21 1. Meteorological Events 21 2. Other Pollution Events that Cause Closures 23 E. Water Quality Monitoring Plan 23 1. Frequency of Monitoring 23 2. Monitoring Stations 24 3. Analysis of Water Samples 24 4. Toxic or Chemical Spills 24 5. Harmful Algae Blooms 24 6. Annual Evaluation of Compliance with NSSP Criteria 25 F. Closure Implementation Plan for the Providence River Conditional Area (GA 16) 27 1. Implementation of Closure 27 G. Re-opening Criteria 28 1. Flushing Time 29 2. Shellstock Depuration Time 29 3. Treatment Plant Performance Standards 30 H. Annual Reevaluation 32 I. Literature Cited 32 i Appendix A: Conditional Area Closure Checklist 34 Appendix B: Quahog tissue metals and PCB results 36 List of Figures Figure 1: Providence River, RI location map. ................................................................................ 6 Figure 2: Providence River watershed with municipal sewer service areas .................................. -

Juniper Hill Cemetery

_______________ PS Form io-g CUB Nc. 1O2418 Rev. 8-88 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. Name of Property historic name: Juniper HillCemetery other name/site number: N/A 2. Location street & number: 24 Sherry Avenue not for publication: N/A city/town: Bristol vicinity: N/A state: RI county: Bristol code: 001 zip code: 02809 3. Classification Ownership of Property: private Category of Property: Site Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing 2 buildings 1 sites 1 structures objects 4 0 Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: 0 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A ______________________________ USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Page 2 Property name Juniper Hill Cemetery. Bristol County.RI 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ,.j_ nomination - request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFRRart 60. In my opinion, the property ..j_. meets - does not meet the National Register Criteria. - See continuation sheet. rc ‘ - Signature of certifying official Date State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property - meets does not meet the National Register criteria. See continuation sheet. Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 5. National Park Service Certification I hereby certify that this property is: entered in the National Register See continuation sheet. -

Genealogy of the Fenner Family

GENEALOGY OF THE Fenner Family -c^^o^. No ^ ^. ROOT. j-NewP(?-RT,K. I., ii^2: /] ('jlL 4{j6 [Reprinted from the Rhode Island Historical Magazine.] SKETCH OF CAPT. ARTHUR FENNER, OF PROVI- DENCE. A PAPER READ BEFOliE THE E. I. HISTORICAL SOCIETY, MARCH 23 AND APRIL 6, 1886, BY REV. J. P. ROOT. fLYMOUTH had its valiant Capt. Miles Standish. Prov- idence could boast of its brave and wise Capt. Arthur Fenner. If the former became more noted for his military exploits, the latter was more distinguished for commanding ability in the conduct of civil affairs. The Providence Cap- tain was less hasty and imperious in spirit than Standish, not so quick to buckle on the sword, but he may be pardoned for the possession of a more peaceable frame of mind. He certainly did not seek to make occasion for the practice of his military skill. It is generally admitted that Williams and the other colonists of our own plantation adopted and quite steadily pursued a more liberal and humane policy to- wards the Aborigines than prevailed in either of the colo- nies about her.( Fenner was not only a soldier, but was pos- sessed of statesmanlike qualities of no mean nature. He was also an expert engineer and^urveyDr. In his varied re- lations to town and colonial ^ife he shewed himself a man of admirable genius, with a mind well balanced and sagacious. His comprehensive qualities made him an energetic, shrewd and trustworthy leader in practical affairs. His age, midway between the older and the younger inhabitants, brought him into sympathy with men both of the first and second gen- erations. -

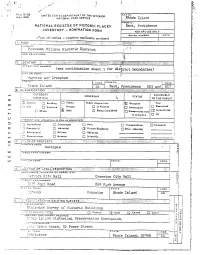

Pawtuxet Village Historic District" Lying in Both Cranston and Warwick, Rhode Island, Can Be Defined As Follows: Beginning in Cranston

__________________ _________________________________________ ______________________________________ I- -4- Foso, 10-300 STATE: UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Juiy 1969 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Rhode Island COUNTY. NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Kent, Providence INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR N PS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE Type zill entries - complete applicable sections jJNAME C L’MMON Pa.tuxet Vi1lace Historic District AND/OR HISTORIC: 12 L0cAT *..:;:. .:I:.:.:.::;.<... .1:?::::::.:..:..::;:...:. STREET ANONUMBER: 4t.r see continuation sheet 1 for district boundaries CJTYORTOWN: -. ‘ - Ja_!.,ick an6 Cranston -,. : STATE CODE COUNTYt CODE R?ocie Island Kent Providence 003 and 007 !3CLASSFICt1_IOr’1 . CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS Check One To THE PUBLIC District Building fl Public Public Acquisition: Occupied Yes: J .. Restricted Site E Structure Private D In Process C Unoccupied C Unrestricted C Object Both Being Considered Preservation work No ., In progress C -R EStflN T USE Check One or More as Appropriate : Agricultural C Government Pork : C Transportation C Comments Commercial C Industrial Private Residence Other Specifr 4 Educorioral C Military Religious - fl Entertainment Museum C Scientiljc - ;:::__:: z OF PROPERTY ;:.:*.*::.:.:: OWN £R*s N AME: . multiple . AND NUMBER: TV OR TOWN: STATE: cooc 5. OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGsTRY OF OEEDS. ETC: . ..anrick City Hall Cranston CIty Hall ZTRLIT AND NUMBER: . -. 37 Post Road 869 Prk Avenue CITY Oh TOWN: STATE CODE Cranston Rhode Island LjL& IN ExISTiNG.SI.JRYEY:S.:::AH:::_ --.. TE OF SURVEY: H State:-ride Suney of Historic Buildings - , OF SJRVEV:1072 C Federal State C County C Local I -p05] TORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Z - Isad -istoncal Preservation Corr-risson 5 . C . -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: _Cedar Hill _________________________________________________ Other names/site number: Reed, Mrs. Elizabeth I.S., Estate;_________________________ “Clouds Hill Victorian House Museum”____________________ Name of related multiple property listing: ____N/A_______________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing _____ _______________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: __4157 Post Road___________________________________________ City or town: _Warwick____ State: __RI_ Zip Code: __ 02818___County: _Kent______ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination ___ request for determination -

Papers of the American Slave Trade

Cover: Slaver taking captives. Illustration from the Mary Evans Picture Library. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Papers of the American Slave Trade Series A: Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society Part 2: Selected Collections Editorial Adviser Jay Coughtry Associate Editor Martin Schipper Inventories Prepared by Rick Stattler A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society [microfilm] / editorial adviser, Jay Coughtry. microfilm reels ; 35 mm.(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Martin P. Schipper, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society. Contents: pt. 1. Brown family collectionspt. 2. Selected collections. ISBN 1-55655-650-0 (pt. 1).ISBN 1-55655-651-9 (pt. 2) 1. Slave-tradeRhode IslandHistorySources. 2. Slave-trade United StatesHistorySources. 3. Rhode IslandCommerce HistorySources. 4. Brown familyManuscripts. I. Coughtry, Jay. II. Schipper, Martin Paul. III. Rhode Island Historical Society. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) V. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society. VI. Series. [E445.R4] 380.14409745dc21 97-46700 -

A Vision for Providence

AA VISIONVISION FORFOR PROVIDENCEPROVIDENCE FULFILLING OUR VAST POTENTIAL By Mayor David N. Cicilline building on our strength DEVELOPING A 21ST-CENTURY ECONOMY IN THE CHARACTER OF PROVIDENCE building on our strength Developing a 21st-Century Economy in the Character of Providence table of contents Preface Introduction 1 Past, Present and Future 1 Foundation of Planning Efforts 3 Guiding Principles 4 A Vision for Providence Refining the Vision 6 Next Steps Investing in the Future: The Comprehensive Plan Update 8 Managing Growth Now: The Zoning Ordinance Update 9 Investing in People: Providing Access to Jobs and Training 10 Investing in Neighborhoods: Housing, Businesses and Infrastructure 11 Investing in Services: Permitting 13 Providence Investment Summary Overview 14 Summary Table: Investment by Neighborhood 15 Citywide Public Investment Maps 16 Investment Project Summaries by Neighborhood 20 “Preservation of character and growth—these will be the guiding principles for the years ahead. Our ambitions for our future should not be smaller than the achievements of our past.” Mayor David N. Cicilline City of Providence Mayor David N. Cicilline October 2005 building on our strength Developing a 21st-Century Economy in the Character of Providence preface Introduction For several years, prominent national observers acclaimed Providence as a city with great potential. They praised our city’s unique character with its historic charm, lively cultural scene, educated workforce, and proximity to natural beauty. Unfortunately, potential wasn’t enough. Investors remained wary of an unpredictable regulatory environment and withheld their capital. Three years ago, Providence residents voted to change that. They gave me and my administration a mandate to bring honesty, predictability, and fiscal responsibility to City Hall. -

City Walk Phase 2 Conceptual Review

Staff Report: City Walk Phase 2 Conceptual Review –Upper South Providence, Lower South Providence, Elmwood – Wards 9, 10, 11 (For Action) Presented at February 20, 2019 BPAC meeting Project Background The City of Providence Department of Planning and Development seeks comments from the BPAC regarding the conceptual plans for Phase 2 of City Walk. The plans involve striping and signage improvements on Broad Street between Elmwood Ave and Hawthorne Ave. This will be a conceptual level review of the project and the first of two reviews by the Commission. The City has funding from the State Transportation Improvement Plan (TIP) to complete a portion of City Walk, the vision to connect nine Providence neighborhoods to each other, to Roger Williams Park, and India Point Park by means of safe places to walk and to bike. The funded portion of the vision extends from the intersection of Clifford Street and Richmond Street downtown across I-95 to Broad Street, and south on Broad Street to Hawthorne Ave, which is the entrance to Roger Williams Park. That project is split into two phases, with Phase 1 extending from downtown to the intersections of Pine Street and Friendship Street with Broad Street, and Phase 2 consisting of Broad Street. The schedule for the two phases is for implementation of Phase 1 in 2019 and of Phase 2 in 2020. Throughout 2018, the City conducted public engagement to ask the community what the improvements on Broad Street should look like. These included two public meetings, the first to identify design preferences, challenges on Broad Street, and examples of potential options, and the second to take a closer look at design options.