First Satellite Tracks of the Endangered Black-Capped Petrel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bermuda Biodiversity Country Study - Iii – ______

Bermuda Biodiversity Country Study - iii – ___________________________________________________________________________________________ EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The Island’s principal industries and trends are briefly described. This document provides an overview of the status of • Statistics addressing the socio-economic situation Bermuda’s biota, identifies the most critical issues including income, employment and issues of racial facing the conservation of the Island’s biodiversity and equity are provided along with a description of attempts to place these in the context of the social and Government policies to address these issues and the economic needs of our highly sophisticated and densely Island’s health services. populated island community. It is intended that this document provide the framework for discussion, A major portion of this document describes the current establish a baseline and identify issues requiring status of Bermuda’s biodiversity placing it in the bio- resolution in the creation of a Biodiversity Strategy and geographical context, and describing the Island’s Action Plan for Bermuda. diversity of habitats along with their current status and key threats. Particular focus is given to the Island’s As human use or intrusion into natural habitats drives endemic species. the primary issues relating to biodiversity conservation, societal factors are described to provide context for • The combined effects of Bermuda’s isolation, analysis. climate, geological evolution and proximity to the Gulf Stream on the development of a uniquely • The Island’s human population demographics, Bermudian biological assemblage are reviewed. cultural origin and system of governance are described highlighting the fact that, with 1,145 • The effect of sea level change in shaping the pre- people per km2, Bermuda is one of the most colonial biota of Bermuda along with the impact of densely populated islands in the world. -

Letter from the Desk of David Challinor August 2001 About 1,000

Letter From the Desk of David Challinor August 2001 About 1,000 miles west of the mid-Atlantic Ridge at latitude 32°20' north (roughly Charleston, SC), lies a small, isolated archipelago some 600 miles off the US coast. Bermuda is the only portion of a large, relatively shallow area or bank that reaches the surface. This bank intrudes into the much deeper Northwestern Atlantic Basin, an oceanic depression averaging some 6,000 m deep. A few kilometers off Bermuda's south shore, the depth of the ocean slopes precipitously to several hundred meters. Bermuda's geographic isolation has caused many endemic plants to evolve independently from their close relatives on the US mainland. This month's letter will continue the theme of last month's about Iceland and will illustrate the joys and rewards of longevity that enable us to witness what appears to be the beginnings of landscape changes. In the case of Bermuda, I have watched for more than 40 years a scientist trying to encourage an endemic tree's resistance to an introduced pathogen. My first Bermuda visit was in the spring of 1931. At that time the archipelago was covered with Bermuda cedar ( Juniperus bermudiana ). This endemic species was extraordinarily well adapted to the limestone soil and sank its roots deep into crevices of the atoll's coral rock foundation. The juniper's relatively low height, (it grows only 50' high in sheltered locations), protected it from "blow down," a frequent risk to trees in this hurricane-prone area. Juniper regenerated easily and its wood was used in construction, furniture, and for centuries in local boat building. -

Molecular Ecology of Petrels

M o le c u la r e c o lo g y o f p e tr e ls (P te r o d r o m a sp p .) fr o m th e In d ia n O c e a n a n d N E A tla n tic , a n d im p lic a tio n s fo r th e ir c o n se r v a tio n m a n a g e m e n t. R u th M a rg a re t B ro w n A th e sis p re se n te d fo r th e d e g re e o f D o c to r o f P h ilo so p h y . S c h o o l o f B io lo g ic a l a n d C h e m ic a l S c ie n c e s, Q u e e n M a ry , U n iv e rsity o f L o n d o n . a n d In stitu te o f Z o o lo g y , Z o o lo g ic a l S o c ie ty o f L o n d o n . A u g u st 2 0 0 8 Statement of Originality I certify that this thesis, and the research to which it refers, are the product of my own work, and that any ideas or quotations from the work of other people, published or otherwise, are fully acknowledged in accordance with the standard referencing practices of the discipline. -

Conservation Action Plan Black-Capped Petrel

January 2012 Conservation Action Plan for the Black-capped Petrel (Pterodroma hasitata) Edited by James Goetz, Jessica Hardesty-Norris and Jennifer Wheeler Contact Information for Editors: James Goetz Cornell Lab of Ornithology Cornell University Ithaca, New York, USA, E-mail: [email protected] Jessica Hardesty-Norris American Bird Conservancy The Plains, Virginia, USA E-mail: [email protected] Jennifer Wheeler U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Arlington, Virginia, USA E-mail: [email protected] Suggested Citation: Goetz, J.E., J. H. Norris, and J.A. Wheeler. 2011. Conservation Action Plan for the Black-capped Petrel (Pterodroma hasitata). International Black-capped Petrel Conservation Group http://www.fws.gov/birds/waterbirds/petrel Funding for the production of this document was provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Table Of Contents Introduction . 1 Status Assessment . 3 Taxonomy ........................................................... 3 Population Size And Distribution .......................................... 3 Physical Description And Natural History ................................... 4 Species Functions And Values ............................................. 5 Conservation And Legal Status ............................................ 6 Threats Assessment ..................................................... 6 Current Management Actions ............................................ 8 Accounts For Range States With Known Or Potential Breeding Populations . 9 Account For At-Sea (Foraging) Range .................................... -

Detailed Species Account from the Threatened Birds of the Americas

JAMAICA PETREL Pterodroma caribbaea E/Ex4 Predation by introduced mongooses and human exploitation for food caused the extinction or near- extinction of this very poorly known seabird of the forested mountains of eastern Jamaica, which recent evidence suggests is (or was) a good species. DISTRIBUTION The Jamaica Petrel (see Remarks 1) formerly nested in the Blue Mountains of Jamaica, where specimens were taken at the summit in 1829 (Bancroft 1835) and in Cinchona Plantation on the south flank at about 1,600 m in November and December 1879 (Bond 1956b, Benson 1972, Imber 1991). Carte (1866) was aware of the species in the north-eastern end of Jamaica, and the John Crow Mountains, adjacent to the Blue Mountains, were known to harbour birds at the end of the nineteenth century (see Scott 1891-1893); Bourne (1965) reported that “birds are still said to call at night” in the John Crow Mountains. It is conceivable that the species also nested in the mountains of Guadeloupe and Dominica, since there is evidence of nesting black petrels in Guadeloupe (see Bent 1922, Murphy 1936, Imber 1991, Remarks 2 under Black-capped Petrel Pterodroma hasitata), and Verrill (1905) reported that the Jamaica Petrel nested in Dominica (see Remarks 2) in La Birne, Pointe Guignarde, Lance Bateaux, Morne Rouge and Scott's Head. Virtually nothing is known about the species's range at sea other than Bond's (1936) report of a possible sighting west of the Bimini Group, Bahama Islands. POPULATION When first reported in the literature in 1789 it was considered plentiful (see Godman 1907-1910). -

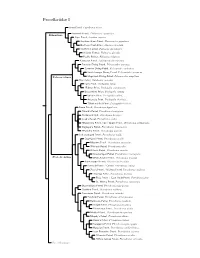

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma -

Threats to Seabirds: a Global Assessment 2 3 4 Authors: Maria P

1 Threats to seabirds: a global assessment 2 3 4 Authors: Maria P. Dias1*, Rob Martin1, Elizabeth J. Pearmain1, Ian J. Burfield1, Cleo Small2, Richard A. 5 Phillips3, Oliver Yates4, Ben Lascelles1, Pablo Garcia Borboroglu5, John P. Croxall1 6 7 8 Affiliations: 9 1 - BirdLife International. The David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QZ UK 10 2 - BirdLife International Marine Programme, RSPB, The Lodge, Sandy, SG19 2DL 11 3 – British Antarctic Survey. Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, 12 Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 13 4 – Centre for the Environment, Fishery and Aquaculture Science, Pakefield Road, Lowestoft, NR33, UK 14 5 - Global Penguin Society, University of Washington and CONICET Argentina. Puerto Madryn U9120, 15 Chubut, Argentina 16 * Corresponding author: Maria Dias, [email protected]. BirdLife International. The David 17 Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QZ UK. Phone: +44 (0)1223 747540 18 19 20 Acknowledgements 21 We are very grateful to Bartek Arendarczyk, Sophie Bennett, Ricky Hibble, Eleanor Miller and Amy 22 Palmer-Newton for assisting with the bibliographic review. We thank Rachael Alderman, Pep Arcos, 23 Jonathon Barrington, Igor Debski, Peter Hodum, Gustavo Jimenez, Jeff Mangel, Ken Morgan, Paul Sagar, 24 Peter Ryan, and other members of the ACAP PaCSWG, and the members of IUCN SSC Penguin Specialist 25 Group (Alejandro Simeone, Andre Chiaradia, Barbara Wienecke, Charles-André Bost, Lauren Waller, Phil 26 Trathan, Philip Seddon, Susie Ellis, Tom Schneider and Dee Boersma) for reviewing threats to selected 27 species. We thank also Andy Symes, Rocio Moreno, Stuart Butchart, Paul Donald, Rory Crawford, 28 Tammy Davies, Ana Carneiro and Tris Allinson for fruitful discussions and helpful comments on earlier 29 versions of the manuscript. -

Species Booklet

About NEPA The National Environment and Planning Agency (NEPA) is the lead government agency with the mandate for environmental protection, natural resource management, land use and spatial planning in Jamaica. NEPA, through the Town and Country Planning Authority and the Natural Resource Conservation Authority, operates under a number of statutes which include: The Town and Country Planning Act The Land Development and Utilization Act The Beach Control Act The Watershed Protection Act The Wild Life Protection Act The Natural Resources Conservation Authority Act. Vision NEPA’s vision is “for a Jamaica where natural resources are used in a sustainable way and that there is a broad understanding of environment, planning and development issues, with extensive participation amongst citizens and a high level of compliance with relevant legislation.” Mission “To promote Sustainable Development by ensuring the protection of the envi- ronment and orderly development in Jamaica through highly motivated staff performing at the highest standard.” A view of the Blue Mountains The agency executes its mandate through the development of environmental and planning policies; monitoring the natural resource assets and the state of Jamaica’s environment; enforcement of environmental and planning legislation; processing of applications for environmental permits and licences; preparing Town and Parish Development Plans and Parish Development Orders; providing environmental and land use database systems; advising on land use planning and development; public -

A Black-Capped Petrel Specimen from Florida the Black-Capped Petrel (Pterodroma Hasitata) Is a Rare Bird Anywhere in North America (Palmer, 1962)

Florida Field Naturalist Vol. 2 Spring 1974 gulls circled with the downwind passage about 2 t,o 4 meters over our heads. When we tossed a fish into the path of one, it caught the fish easily, often performing int,ricate aerial maneuvers to do so. We counted only 12 misses in 97 tosses in which we judged t,he adult should have caught the fish. The juvenile, on the other hand, hovered out of the mainstream of the flock approximately 10 to 13 meters above and to one side of us. It called frequently, behavior rarely exhibited by the adults, and whenever we t,hrew a fish in its direct,ion, it attempted to avoid rather than catch it. It ap- peared to be curious about the other gulls' activity but seemed unaware of how to become involved and what to do, After several minut,es of hovering nearby, t,he young bird joined the flight pattern of the adults but remained about 4 to 9 meters over our heads. We attempted to direct fish toward this young individual and in circumstances similar t,o those of the adult the juvenile caught only one of 23 fish. In four of these cases an adult stole the fish before t,he young could respond. The one fish the young captured was the last one thrown, approxin~at,elyten minutes after it joined the flock. Wat,ching this bird, it was obvious to us that at first it was attracted to the flock of gulls, and only after a period of time did it realize that food was available. -

On the Brink of Extinction: Saving Jamaica’S Vanishing Species

The Environmental Foundation of Jamaica in association with Jamaica Conservation and Development Trust present The 7th Annual EFJ Public Lecture On the Brink of Extinction: Saving Jamaica’s Vanishing Species Dr. Byron Wilson, Senior Lecturer, Department of Life Sciences, University of the West Indies, Mona October 20, 2011, 5:30 pm FOREWORD The Environmental Foundation of Jamaica (EFJ) is very pleased to welcome you to our 7th Annual Public Lecture. The Lecture this year is being organized in partnership with our member and long standing partners at the Jamaica Conservation and Development Trust (JCDT). JCDT has been a major player not only in Protected Areas and Management of the Blue and John Crow Mountain National Park, but also in the area of public awareness and education with features such as the National Green Expo held every other year. Like all our work over the last 18 years, we have balanced the Public Lectures between our two major areas of focus – Child Development and Environmental Management. This year, our environmental lecture will focus on issues of biodiversity and human impact on ecological habitats. Our lecturer, Dr. Byron Wilson is a Senior Lecturer in the University of the West Indies. He is an expert in conservation biology and has dedicated his research to the ecology and conservation of the critically endangered Jamaican Iguana and other rare endemic reptile species. In addition to Dr. Wilson’s work, the EFJ has partnered with Government, Researchers and Conservationists to study and record critical information and data on Endemic and Endangered Species across Jamaica, including the establishment of the UWI/EFJ Biodiversity Centre in Port Royal, the Virtual Herbarium and the publication of the “Endemic Trees of Jamaica” book. -

Hatteras Black-Capped Petrel Planning Meeting Hatteras, North Carolina June 16 and 17, 2009 – Meeting Days

HATTERAS BLACK-CAPPED PETREL PLANNING MEETING HATTERAS, NORTH CAROLINA JUNE 16 AND 17, 2009 – MEETING DAYS. JUNE 18, 2009 – ON BOAT Attendees, current affiliation Chris Haney, Defenders of Wildlife, [email protected] Kate Sutherland, Seabirding Pelagic Trips, [email protected] Jennifer Wheeler, USFWS, [email protected] Brian Patteson, Seabirding Pelagic Trips, [email protected] Stefani Melvin, USFWS, [email protected] Dave Lee, Tortoise Reserve, [email protected] Ted Simons, North Carolina State University, [email protected] Jessica Hardesty, American Bird Conservancy, [email protected] Marcel Van Tuinen, University of North Carolina, [email protected] Will Mackin, Jadora (and wicbirds.net), [email protected] David Wingate, Cahow Project, retired, [email protected] Elena Babij, USFWS, [email protected] Wayne Irvin, photographer, retired, [email protected] Britta Muiznieks, National Park Service, [email protected] Discussions: David Wingate – Provided a overview of the Cahow (Bermuda Petrel) including the history, lessons learned, and management actions undertaken for the petrel. The importance of working with all stakeholders to conserve a species was stressed. One key item was that there must be more BCPEs than we know as so many seen at sea! Do a rough ratio of Cahow sightings to known population; could also use sightings of BCPE to estimate abundance. Ted Simons: Petrel Background: A number of species have been lost to science. He focused on the Hawaiian/Dark-rumped Petrel (lost and re-discovered). Points covered: • Probably occurred at all elevations • Now scattered, in isolated locations (not really colonial – 30 m to 130 m apart) • Intense research – metabolic, physiologic characteristics of adults, chicks and eggs; pattern of adult tending and feeding, diet and stomach oil • Management: fencing herbivores out (fences are source of mortality) • Estimated life history and stable age distribution; clues on where to focus management • K-selected: Reduce adult mortality! Improve nesting success. -

CAHOW RECOVERY PROGRAM for Bermuda’S Endangered National Bird 2017 – 2018 Breeding Season Report

CAHOW RECOVERY PROGRAM For Bermuda’s Endangered National Bird 2017 – 2018 Breeding Season Report BERMUDA GOVERNMENT Compiled by: Jeremy Madeiros, Senior Conservation Officer Terrestrial Conservation Division Department of Environment and Natural Resources “To conserve and restore Bermuda’s natural heritage” 2017 - 2018 Report on Cahow Recovery Program 1 Compiled by: Jeremy Madeiros Senior Terrestrial Conservation Officer RECOVERY PROGRAM FOR THE CAHOW (Bermuda Petrel) Pterodroma cahow BREEDING SEASON REPORT For the Nesting Season (October 2017 to June 2018) Of Bermuda’s Endangered National Bird Fig. 1: 80-day old Cahow (Bermuda petrel) fledgling with remnants of natal down (photo by David Liittschwager) Cover Photo: drone photo of Green Island (foreground) And Nonsuch Island in the Castle Islands Nature Reserve, The sole breeding location of the Cahow (Patrick Singleton) 2017 - 2018 Report on Cahow Recovery Program 2 Compiled by: Jeremy Madeiros Senior Terrestrial Conservation Officer CONTENTS: Page No. Section 1: Executive Summary: ............................................................................................... 5 Section 2: (2a) Management actions for 2017-2018 Cahow breeding season: ......................................... 7 (2b) Use of candling to check egg fertility and embryo development: .................................. 10 (2c) Cahow Recovery Program – summary of 2017/2018 breeding season: ......................... 11 (2d) Breakdown of breeding season results by nesting island: .............................................