The State of Charlotte Harbor, Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![WPFLS-12NE 82°18'45"W 82°15'0"W [ # ] 26°52'30"N !S 26°52'30"N ( Charlotte Harbor Palm Island Preserve State Marina Park [ K (!S ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8100/wpfls-12ne-82%C2%B01845-w-82%C2%B0150-w-26%C2%B05230-n-s-26%C2%B05230-n-charlotte-harbor-palm-island-preserve-state-marina-park-k-s-68100.webp)

WPFLS-12NE 82°18'45"W 82°15'0"W [ # ] 26°52'30"N !S 26°52'30"N ( Charlotte Harbor Palm Island Preserve State Marina Park [ K (!S ]

k Lemon AB775 Bay Aquatic Preserve Geographic Response Plan Map: WPFLS-12NE 82°18'45"W 82°15'0"W [ # ] 26°52'30"N !S 26°52'30"N ( Charlotte Harbor Palm Island Preserve State Marina Park [ k (!S ] 775 Charlotte Harbor )" Preserve State Parkk Don Pedro State Park L e k m o n B · a ! Don y !d Pedro Island # State Parkk XXX GASPARILLA RD WPFLS12-01 # Don Pedro Island State Park & # Recreation Area 771 C )" ora l C k re ek Lemon Bay y[ [ Aquatic Preserve (!S ] Little Gasparilla Pass (closed) !d Little Gasparilla Island!¤ ¡[ (!S (!S Placida d Placida Park ! Harbor d 500 # k ! e e Charlotte r # [ S C Harbor (! l ] ra XXX o Preserve C WPFLS12-04 State Creek tfish Lemon Bay Park Ca Aquatic Preserve k (South) Gulf ¼[ Gasparilla !¢ Dog of Island Sound- Bird 2400 Mexico Key Charlotte Harbor Aquatic 2400 (!h Preservek ass F WPFLS12-02 illa P XXX spar Gasparilla Pass Ga 7800 26°48'45"N 2000 k 26°48'45"N 82°18'45"W Map Continued on Page: WPFLS-12SE Cape Haze82°15'0"W Aquatic Mangroves k Environmentally Sensitive Areas Bio-Socioeconomic !¤ Manatee Preserve Summer Protection Priority Uncle Henry's Gasparilla Sound- \[ Beach Access Sea Turtle Nestingh Beach [ Marina Marina (! Sector Jacksonville XXX A - Protect First · ] Charlotte Harbor Sector St. Petersburg ! Airport v[ Resort Aquaculture Leases Aquatic Preserve XX B - Protect after A Areas NERR y[ Federal Managed Areas Mobile Sector Aquaculture j[ X C - Protect after B Areas k[ National Park State Managed Areas Aquatic Preserve/State Park «[ Response Methods ^ Piping Plover State Waters/County Line -

3Hpwycknam2nldx7.Pdf

The Heron Herald, Page 1 Another Seabreeze Publication VOL. 5 NO. 10 www.seabreezecommunications.com OCTOBER 2019 A Warm Welcome To Our New By Paula Short On Thursday, Sept. 5, friends and neighbors came together at Community Association/Office Manager Cass Cay Restaurant in Burnt Store Marina to wish Sandy Patrice Merritt would and joined the Army. During that time, she received a Funk a wonderful retirement. For 20 years, Sandy has been the like to convey her gratitude Bachelor of the Arts degree from the University of Hawaii pivotal person for the community, serving as our Community for the opportunity to serve and worked as a site manager for nearly 30 years. In 2013, Association Manager (CAM) in the POA office. If you needed our beautiful community. she retired from the Army Reserves as a hand grenade and information on virtually any community issue, Sandy always She is looking forward to administration instructor. Patrice met her husband Saxon had the answer. If you were having a home in BSL built working with our Board in 2015, while he was there on a contract. She left Hawaii and lived out-of-state, Sandy was your eyes and ears with of Directors and friendly in 2016 and joined him at his home in Punta Gorda Isles. the builder. If you needed an outside reference for most any staff when she returns from For nearly three years, she was employed as a portfolio service, Sandy was the one to call. She was the liaison between Africa in the latter part of manager for 11 associations. -

A Addison Bay, 64 Advanced Sails, 351

FL07index.qxp 12/7/2007 2:31 PM Page 545 Index A Big Marco Pass, 87 Big Marco River, 64, 84-86 Addison Bay, 64 Big McPherson Bayou, 419, 427 Advanced Sails, 351 Big Sarasota Pass, 265-66, 262 Alafia River, 377-80, 389-90 Bimini Basin, 137, 153-54 Allen Creek, 395-96, 400 Bird Island (off Alafia River), 378-79 Alligator Creek (Punta Gorda), 209-10, Bird Key Yacht Club, 274-75 217 Bishop Harbor, 368 Alligator Point Yacht Basin, 536, 542 Blackburn Bay, 254, 260 American Marina, 494 Blackburn Point Marina, 254 Anclote Harbors Marina, 476, 483 Bleu Provence Restaurant, 78 Anclote Isles Marina, 476-77, 483 Blind Pass Inlet, 420 Anclote Key, 467-69, 471 Blind Pass Marina, 420, 428 Anclote River, 472-84 Boca Bistro Harbor Lights, 192 Anclote Village Marina, 473-74 Boca Ciega Bay, 409-28 Anna Maria Island, 287 Boca Ciega Yacht Club, 412, 423 Anna Maria Sound, 286-88 Boca Grande, 179-90 Apollo Beach, 370-72, 376-77 Boca Grande Bakery, 181 Aripeka, 495-96 Boca Grande Bayou, 188-89, 200 Atsena Otie Key, 514 Boca Grande Lighthouse, 184-85 Boca Grande Lighthouse Museum, 179 Boca Grande Marina, 185-87, 200 B Boca Grande Outfitters, 181 Boca Grande Pass, 178-79, 199-200 Bahia Beach, 369-70, 374-75 Bokeelia Island, 170-71, 197 Barnacle Phil’s Restaurant, 167-68, 196 Bowlees Creek, 278, 297 Barron River, 44-47, 54-55 Boyd Hill Nature Trail, 346 Bay Pines Marina, 430, 440 Braden River, 326 Bayou Grande, 359-60, 365 Bradenton, 317-21, 329-30 Best Western Yacht Harbor Inn, 451 Bradenton Beach Marina, 284, 300 Big Bayou, 345, 362-63 Bradenton Yacht Club, 315-16, -

Late Holocene Sea Level Rise in Southwest Florida: Implications for Estuarine Management and Coastal Evolution

LATE HOLOCENE SEA LEVEL RISE IN SOUTHWEST FLORIDA: IMPLICATIONS FOR ESTUARINE MANAGEMENT AND COASTAL EVOLUTION Dana Derickson, Figure 2 FACULTY Lily Lowery, University of the South Mike Savarese, Florida Gulf Coast University Stephanie Obley, Flroida Gulf Coast University Leonre Tedesco, Indiana University and Purdue Monica Roth, SUNYOneonta University at Indianapolis Ramon Lopez, Vassar College Carol Mankiewcz, Beloit College Lora Shrake, TA, Indiana University and Purdue University at Indianapolis VISITING and PARTNER SCIENTISTS Gary Lytton, Michael Shirley, Judy Haner, STUDENTS Leslie Breland, Dave Liccardi, Chuck Margo Burton, Whitman College McKenna, Steve Theberge, Pat O’Donnell, Heather Stoffel, Melissa Hennig, and Renee Dana Derickson, Trinity University Wilson, Rookery Bay NERR Leda Jackson, Indiana University and Purdue Joe Kakareka, Aswani Volety, and Win University at Indianapolis Everham, Florida Gulf Coast University Chris Kitchen, Whitman College Beth A. Palmer, Consortium Coordinator Nicholas Levsen, Beloit College Emily Lindland, Florida Gulf Coast University LATE HOLOCENE SEA LEVEL RISE IN SOUTHWEST FLORIDA: IMPLICATIONS FOR ESTUARINE MANAGEMENT AND COASTAL EVOLUTION MICHAEL SAVARESE, Florida Gulf Coast University LENORE P. TEDESCO, Indiana/Purdue University at Indianapolis CAROL MANKIEWICZ, Beloit College LORA SHRAKE, TA, Indiana/Purdue University at Indianapolis PROJECT OVERVIEW complicating environmental management are the needs of many federally and state-listed Southwest Florida encompasses one of the endangered species, including the Florida fastest growing regions in the United States. panther and West Indian manatee. Watershed The two southwestern coastal counties, Collier management must also consider these issues and Lee Counties, commonly make it among of environmental health and conservation. the 5 fastest growing population centers on nation- and statewide censuses. -

Street Map of Boca Grande Neighborhoods

Street Map of Boca Grande Neighborhoods Gasparilla Island, Florida North End Directly on the Gulf of Mexico Gasparilla at the mouth of Charlotte Harbor. Pass Boca Grande BEACH Gulf DEEDED North BOCA GRANDE CAUSEWAY Shores ACCESS condo North PRIVATE complex TO MAINLAND GASPARILLA PASS BLVD. Cole Boca SUNSETCIRCLE PINES Key Grande Village Grande Quay Boca Grande Club Marina N. ISLAND CT. ISLAND N. Village South End BEACHFRONT LOTS Gulf of Mexico THE TRESTLE FISHING PIER Seawatch The LAKE Courtyard ORIGINAL SITE OF GASPARILLA OLD GASPARILLA Harbor RESIDENTIAL Residential FISHERY Charlotte Beachfront lots – UNPLATED PARCEL – Dunes of Boca townhouse villas Sea Oats LARGE LOTS GULF SHORES DR. SHORES GULF ~ Gasparilla condo complex & Boca Grande RESIDENTIAL Sound ~ Real Estate, Inc. ~ Peacon’s Branch Office DR. COVE PEEKINS Cove The Boca Grande Club – UNPLATED PARCEL – condos, townhouse villas, ROAD GASPARILLA private homes The GROUPER HOLE DR. HOLE GROUPER Kitchen ~ ~ Live Oak Key ~ Grouper NORTH END Hole ~ From Cole Key to the 1. Charlotte / Lee County line CHARLOTTE COUNTY c 2008 BOCA GRANDE REAL ESTATE, INC. LEE COUNTY GROUPER HOLE CHARLOTTE COUNTY EAST LEE COUNTY CT. NW SHORE GULF SHORES NORTH North End ACRES From the Charlotte / Lee LANE County line to 19th St. th 2. 48st. – NATURE PRESERVE – Gulf Shores SHORE th ROAD GASPARILLA North 45st. Boca Grande Village SNAIL ISLAND CT. NW LAGOON LANE South End SNAIL ISLAND th Gulf of Mexico 40st. LOOMIS AVE. NW AVE. LOOMIS SHORE EAST SHORE ACRES TO SARASOTA Harbor Charlotte LAGOON TO SARASOTA 681 75 LANE LAUREL th 35st. EXIT 193 JACARANDA EXITBLVD. 191 EXIT 182 RIVER ROAD 75 SUMTER BLVD. -

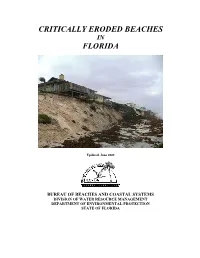

Currently the Bureau of Beaches and Coastal Systems

CRITICALLY ERODED BEACHES IN FLORIDA Updated, June 2009 BUREAU OF BEACHES AND COASTAL SYSTEMS DIVISION OF WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION STATE OF FLORIDA Foreword This report provides an inventory of Florida's erosion problem areas fronting on the Atlantic Ocean, Straits of Florida, Gulf of Mexico, and the roughly seventy coastal barrier tidal inlets. The erosion problem areas are classified as either critical or noncritical and county maps and tables are provided to depict the areas designated critically and noncritically eroded. This report is periodically updated to include additions and deletions. A county index is provided on page 13, which includes the date of the last revision. All information is provided for planning purposes only and the user is cautioned to obtain the most recent erosion areas listing available. This report is also available on the following web site: http://www.dep.state.fl.us/beaches/uublications/tech-rut.htm APPROVED BY Michael R. Barnett, P.E., Bureau Chief Bureau of Beaches and Coastal Systems June, 2009 Introduction In 1986, pursuant to Sections 161.101 and 161.161, Florida Statutes, the Department of Natural Resources, Division of Beaches and Shores (now the Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Beaches and Coastal Systems) was charged with the responsibility to identify those beaches of the state which are critically eroding and to develop and maintain a comprehensive long-term management plan for their restoration. In 1989, a first list of erosion areas was developed based upon an abbreviated definition of critical erosion. That list included 217.6 miles of critical erosion and another 114.8 miles of noncritical erosion statewide. -

Estero River for the Village of Estero

The Significance of the Estero River for the Village of Estero Photo: Florida Department of Environmental Protection Estuary = “Estero” Estero Bay Watershed Estero Bay Watershed: 360 square miles Pine Island Caloosahatchee Sound Matlacha Watershed Pass Watershed Estero River Basin: 66 square miles (45,000 acres) Estero River: Approximately 8 miles long Mean depth of 3.99 feet and a max depth of 12.06 feet (USF, 2013) Estero Bay Aquatic Preserve: 18,829 acres Source: Estero Bay Agency on Bay Management, State of the Bay Update 2014 Halfway Headwaters Wild Turkey Pond Strand Preserve Imperial Marsh Preserve To Estero River Flows (Source, South Lee County Watershed Plan Update, May 14, 2009) History Source: Estero Historical Society Estero River 1957, State Archives of Florida Historical Collection Estero River, Circa 1900 source: FGCU Collection / Koreshan “A Historical Geography of Southwest Florida Waterways , Vol. II Source: Estero Historical Society Pre-Development Conditions 1944 1953 1998 Courtesy: Lee County Natural Resources What happens in the DRGR affects Estero River and Estero Bay 1953 Hydropatterns 2007 Hydropatterns Source: Kevin Erwin, Consulting Ecologist Vegetation (Source: USF, West-Central Florida Tidal Stream Assessment Study, p. 123) Wildlife Listed Animal Species Gulf sturgeon roseate spoonbill American alligator peregrine falcon loggerhead turtle southeastern American kestrel common snook gopher tortoise Number of Known Atlantic green turtle American oystercatcher Native Species leatherback bald eagle Mammals: 37 -

Regional Waterway Management System for Charlotte County, Fla

Regional Waterway Management System for Charlotte County, Florida Robert Swett David Fann Betty Staugler Florida Sea Grant College Program TP 181 June 2012 Regional Waterway Management System for Charlotte County Florida by Robert Swett David Fann Betty Staugler Sea Grant College Program University of Florida Gainesville Submitted to Charlotte County Natural Resources Program June 2012 Contents Contents ........................................................................................................................... i Tables ............................................................................................................................. ii Figures ............................................................................................................................ iii Acknowledgments ...........................................................................................................iv 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 2. Background ................................................................................................................. 2 3. Information Base ......................................................................................................... 3 4. Field Surveys .............................................................................................................. 3 5. Analysis ...................................................................................................................... -

Island-Hopping Along the Beaches of Fort Myers & Sanibel

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 2019 CONTACTS: Francesca Donlan, Miriam Dotson, 239-338-3500 Island-hopping along The Beaches of Fort Myers & Sanibel Find your island by land or water! LEE COUNTY, Fla. -- Most of us dream about it. A tropical vacation. Island-hopping from one exotic, off-the-grid island to another. Not a care in the world. Leaving all of your worries (and maybe even your phone) at home. If this is what you would like to turn into reality, pack up your T-shirts and flip flops and head to The Beaches of Fort Myers & Sanibel on the Gulf of Mexico. Here, you can take the time to unplug. Find your island in this Southwest Florida paradise by land or by water. In Jimmy Buffett style, you may spend days doing absolutely nothing or engaging in serious exploring of these award-winning islands. The Florida of days long past, with unspoiled white sand beaches, exotic wildlife and lush subtropical foliage, can still be found here and it is the perfect oasis where visitors can “get away from it all” and yet still be close to all of the modern amenities. Many of the area’s 100 coastal islands are uninhabited mangrove clusters, while others take visitors' breath away with their beautiful beaches. From shelling to kayaking to beautiful sunsets, visitors come to this destination and find their island creating wonderful vacation memories. Save the date! The sixth annual Island Hopper Songwriter Fest returns Sept. 20-29, 2019. The popular event brings music back to the beach with new artists and new events. -

Manatee County May 8 - May 14, 2020

30 BUSINESS OBSERVER MANATEE COUNTY MAY 8 - MAY 14, 2020 MANATEE COUNTY LEGAL NOTICES FIRST INSERTION FIRST INSERTION FIRST INSERTION NOTICE NOTICE NOTICE OF ACTION swer and any written defenses with the NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE Clerk of the Court and to serve a copy of the undersigned, desiring to engage the undersigned, desiring to engage in TWELFTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT the answer and defenses on or before in business under the fictitious name business under the fictitious name of IN AND FOR MANATEE COUNTY, the 9th day of June, 2020, on Angeline of Lisa Potts Designs intends to Two Sassy Gals intends to register the FLORIDA Attila, Assistant General Counsel, De- register the said name with the Florida said name with the Florida Department Case Number: 19-CA-5477 partment of Highway Safety and Motor Department of State, Division of of State, Division of Corporations, Judge: SNIFFEN Vehicles, 5023 53rd Avenue East, Bra- OFFICIAL Corporations, Tallahassee, FL. Tallahassee, FL. IN RE: Forfeiture of: denton, FL 33203. Failure to file your Lisa Potts Frances Jensen One (1) 2002 Ford Ranger answer and defenses will result in a de- 5622 35th Ct. E. 1904 148th Court East VIN: 1FTYR10U92PA50570 fault being entered against you. Bradenton, FL 34203 Bradenton, FL 34212 TO: Martin Molina WITNESSED by hand and the Seal COURTHOUSE May 8, 2020 20-00547M May 8, 2020 20-00546M Last known Address: 6212 Dundy of the Court on this 28 day of April, Avenue, Gibsonton, FL 33534 2020. FIRST INSERTION FIRST INSERTION YOU ARE HEREBY NOTIFIED that The Honorable Angelina Colonneso a forfeiture action has been filed against Clerk of Court WEBSITES: FICTITIOUS NAME NOTICE FICTITIOUS NAME NOTICE the above described currency by the De- (SEAL) s/ Kathy Steinmetz Notice is hereby given that SAN ANTO- Notice is hereby given that ANGELA partment of Highway Safety and Motor Deputy Clerk NIO SHOE, INC., owner, desiring to WARNER DAVIS, owner, desiring to Vehicles. -

Circumnavigational Trail Data Book PC = Primitive Campsite POI

Circumnavigational Trail Data Book PC = Primitive campsite POI = Point of Interest/landmark C = Campground LA = Laundromat W = Water L = Lodging I = Internet computer PO = Post Office R = Restaurant S = Shower G = medium/lg supermarkets B = Bathroom PI = Put-In g = convenience/camp stores Mile # Type of amenity GPS # on OGT Directions trail Seg- ment (decimal- and degrees) Map # 0 PC/log-book N30.3100 1/1-A On trail (Big Lagoon State W87.4029 Park, Pensacola) 6 PC N30.3181 1/1-A On trail W87.3321 (Gulf Shores National Seashore) N30.3298 1/1-A On trail 8 POI (Ft. Pickens) W87.3018 14.4 W, R N30.3270 1/1-B On trail (Gulf Islands National W87.1809 Seashore Park) 17 L, R, I N30.3329 1/1-B Just before southern end of bridge W87.1438 (Comfort Inn) 18 L, R N30.3357 1/1-B Just past southern end of bridge W87.1338 (Paradise Inn) (1 mile R, W N30.3637 1/1-B 2 miles past bridge on north side north of (Gulf Shores Visitor’s W87.1296 route) Center) 23 PC (Big Sabine Point) N30.3533 1/2A On Santa Rosa Island; water, restrooms and W87.0524 showers .5 mile south. No fires allowed at campsite. (1 mile PI (no facilities) N30.3740 1/2A North side of sound north of W87.0924 route) 27.8 PI (no facilities) N30.3874 1/2A North side of sound W86.9967 35 G, L, I (Best Western), N30.4007 1/2B North side of sound just past bridge. -

Hurricane Charley Preliminary Storm Survey II

Hurricane Charley Preliminary Storm Survey II Disclaimer: Hurricane Charley track and intensity information from our surveys are preliminary. Final official intensity and track will be determined by the National Hurricane Center. By Mark Linhares NWS Senior Meteorologist Birmingham, Alabama National Weather Service Meteorologists surveyed the extensive damage caused by Hurricane Charley. The hurricane affected a large part of Southwest and West Central Florida. The most significant damage occurred in Lee, Charlotte, DeSoto, Hardee, and Polk counties. The hurricane affected parts of Sarasota and Highlands counties to a lesser degree. Preliminary damage was estimated in the tens of billions of dollars. The hurricane damage path was similar to the path taken by Hurricane Donna on September 11, 1960. A strong feeder band associated with Hurricane Charley moved across West Central and Southwest Florida during the early afternoon hours of 13 August 2004. This band produced at least 5 weak tornadoes. Unfortunately, most of these tornadoes occurred in the same areas that sustained maximum damage from the hurricane's eyewall region. Therefore, the survey team was unable to distinguish individual paths and will rely on the time of the damage reports at this time. Future evaluation may make these paths more defined. Hurricane Charley made landfall at 345 PM EDT at Cayo Costa, just north of the barrier island of Captiva in Lee County. Hurricane Charley was a Category 4 hurricane with winds around 140 miles an hour at landfall. The survey team found the most intense damage was coincident with the eyewall region. The eyewall region moved across northern Captiva, Pine Island, and Gasparilla Island, then continued into Punta Gorda, Port Charlotte, and Cleveland.