Sugar Ray in a Tux by Herb Boyd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jackson Intends to Run Fof Mayor

Workshop·on college funding to be held Society to hold Western event New city planning director named SPORTS MENU TIPS A free workshop on the "9 Ways To Beat The The American Cancer Society, Cuyahoga Divi Mayor Jane Campbell recently named Robert High Cost Of College" will be held on Tuesday, January 25 sion, plans to rope in Greater Clevelanders with what should Brown as the new city planning director. The city planning Cavs Beat Boozer's Tips For from 6:30p.m. to 7:30p.m. at the Solon High School be the most extraordinary party in Ohio: the Cattle Baron's director oversees the city's long term land use and zoning Lecture Hall, 33600 Inwood Road in Solon. The workshop BaJI. The inaugural Cattle Baron's BaJI will be Saturday plans aJong with other responsibilities. The position opened Jazz On Road Trip Winter Parties will cover many topics, including how to double or even April 9, in the CLub Lounge at Cleveland Bown's Stadium. up after CampbeiJ chose former City Planning director triple your eligibility for financial aid, how to construct a Tickets and sponsorship opportunities are available now by Chis Ronayne as her new chief of staff. Brown has worked plan to pay college costs, and what colleges will give you calling (216) 241-11777. The Northern Ohio Toyota Deal for the City Planning Commission for 19 years. For the See Page 9 See Page 10 the best financial aid packages. Reservations are required. ers have jumped in the driver's seat as the event's present last 17 years, Brown was the assistant city planning direc For more information call (888) 845-4282. -

Dec 2004 Current List

Fighter Opponent Result / RoundsUnless specifiedDate fights / Time are not ESPN NetworkClassic, Superbouts. Comments Ali Al "Blue" Lewis TKO 11 Superbouts Ali fights his old sparring partner Ali Alfredo Evangelista W 15 Post-fight footage - Ali not in great shape Ali Archie Moore TKO 4 10 min Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 ABC Commentary by Cossell - Some break up in picture Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 British CC Ali gets cut Ali Brian London TKO 3 B&W Ali in his prime Ali Buster Mathis W 12 Commentary by Cossell - post-fight footage Ali Chuck Wepner KO 15 Classic Sports Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 B&W Commentary by Don Dunphy - Ali in his prime Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 Classic Sports Ali in his prime Ali Doug Jones W 10 Jones knows how to fight - a tough test for Cassius Ali Earnie Shavers W 15 Brutal battle - Shavers rocks Ali with right hand bombs Ali Ernie Terrell W 15 Feb, 1967 Classic Sports Commentary by Cossell Ali Floyd Patterson i TKO 12 22-Nov-1965 B&W Ali tortures Floyd Ali Floyd Patterson ii TKO 7 Superbouts Commentary by Cossell Ali George Chuvalo i W 15 Classic Sports Ali has his hands full with legendary tough Canadian Ali George Chuvalo ii W 12 Superbouts In shape Ali battles in shape Chuvalo Ali George Foreman KO 8 Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Gorilla Monsoon Wrestling Ali having fun Ali Henry Cooper i TKO 5 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Henry Cooper ii TKO 6 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only - extensive pre-fight Ali Ingemar Johansson Sparring 5 min B&W Silent audio - Sparring footage Ali Jean Pierre Coopman KO 5 Rumor has it happy Pierre drank before the bout Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 Superbouts Ali at his relaxed best Ali Jerry Quarry i TKO 3 Ali cuts up Quarry Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jimmy Ellis TKO 12 Ali beats his old friend and sparring partner Ali Jimmy Young W 15 Ali is out of shape and gets a surprise from Young Ali Joe Bugner i W 12 Incomplete - Missing Rds. -

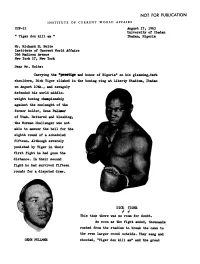

"Tiger Don Kill Ams and the Great C,TP-12 2 Crovd of Outsiders Joyfully Joined the Refrain

NOT FOR PUBLICATION INSTITUTE OF CURR.ENT ORLD APFAIRS C2P-2 17, 1963 University of Ibadan Tiger don kill a Ibadan, Nigeria Mr...Richard H, Nolte Insti,ute .of .Current World iffstrs 366. Nadtson AVenue e ork 17, New ork Dear lh'. Nol.e: Carrying he .eee and honor of Nigeris" on his gleaming,dark shoulders, Diek Tiger climbed in the boxing ring st Liberty Sadtum, Ibadan on August lOth,., and savagely defended his world mi,ddle- weight boxing champio.ns,hiP &gainst he ons!augh of the former holder, ene r of Utah. Battered and bleeding, the Morman bhs!Ienger was no sble to answer he bell for he eighth round of a scheduled ffteen. Although severely . i or ir first fight _he had gone.the distance. In heir second figh he had survived fteen rounds for a disputed, dry. DICK TIG/ This tim here was no room for doubt. s soon as the fight eMed, rushed from the stadium to break the n the even larger crowd Outside They sang and shouted, "Tiger don kill ams and the great C,TP-12 2 crovd of outsiders joyfully joined the refrain. Their gloving diamond-hard faith in the "power of Dick Tiger" had been gloriously sustained. There had been few, if an, Nigerian reservations about the ultimate victory of he Tiger, bu here had been serious msgvings about the weather, the attendance, the real worth of he government's financial investment, and the amount of lrestige and honor the nation would really accrue from a professional prizefight. The weather was marvelous. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS April 13, 1989 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS Yielding to Extraordinary Economic Pres Angola

6628 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS April 13, 1989 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS Yielding to extraordinary economic pres Angola. Already cut off from South African TESTIMONY OF HOWARD sures from the U.S. government, South aid, which had helped stave off well funded PHILLIPS Africa agreed to a formula wherein the anti invasion-scale Soviet-led assaults during communist black majority Transitional 1986 and 1987, UNITA has been deprived by HON. DAN BURTON Government of National Unity, which had the Crocker accords of important logistical been administering Namibia since 1985, supply routes through Namibia, which ad OF INDIANA would give way to a process by which a new joins liberated southeastern Angola. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES government would be installed under United If, in addition, a SWAPO regime were to Thursday, April 13, 1989 Nations auspices. use Namibia's Caprivi Strip as a base for South Africa also agreed to withdraw its anti-UNITA Communist forces, UNITA's Mr. BURTON of Indiana. Mr. Speaker, I estimated 40,000 military personnel from ability to safeguard those now resident in would like to enter a statement by Mr. Howard Namibia, with all but 1,500 gone by June 24, the liberated areas would be in grave ques Phillips of the Conservative Caucus into the to dismantle the 35,000-member, predomi tion. RECORD. In view of recent events in Namibia, nantly black, South West African Territori America has strategic interests in south al Force, and to permit the introduction of ern Africa. The mineral resources concen I think it is very important for all of us who are 6,150 U.N. -

Ohio, the Commencement Was Strange,” Said Louis Gol- Speaker Richard Poutney Advised Phin, Who Lives Next Door

SPORTS MENU TIPS Cadillac show to be held Kid’s Corner Arts Center to present a Cotton Ball The Cadillac LaSalle Club will be hosting the Foluke Cultural Arts Center, Inc. will present it’s “Legacy of Cadillac” show on Sunday, august 19 from 10:00 Ronette Kendell Bell-Moore, first Cotton Ball, (dinner dance) on Saturday, July 28 at Ivy’s Raynell Williams Turn Your Picnic a.m. until 4:00 p.m. at Legacy Village, at the corner of Rich- who is two and a half years old and Catering at GreenMont, 800 S. Green Road from 9 p.m. - 2 mond and Cedar Roads in Lyndhurst. The show is a free, fam- a.m. The attire is casual summer white and tickets are $20.00 Wins Boxing Title Into A Party the daughter of Kendall Moore and ily friendly event. Fins, food, fashions and fun will rule as Jemonica Bell. Her favorite food is in advance and $25.00 the day of the event. A free cruise will be given away as a door prixze. Winner must be present. over 100 classic Cadillacs of all years and types will compete cheese and watermelon. Her favorite for trophies to be awarded at 3:00 p.m. This will be the largest Proceeds benefit Arts Center programming for children and See Page 6 See Page 7 and most prestigious gathering of important Cadillacs in seven toy and character is Dora. She has a youth in need. For information, please refer to www.foluke- states. For information, call Chris Axelrod, (216) 451-2161. -

Montana Kaimin, February 2, 1960 Associated Students of Montana State University

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 2-2-1960 Montana Kaimin, February 2, 1960 Associated Students of Montana State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of Montana State University, "Montana Kaimin, February 2, 1960" (1960). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 3565. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/3565 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MONTANA K A INI MX Montana State University AN INDEPENDENT DAILY NEWSPAPER 59th Year ofPublication, No. 55 Missoula. Montana ' Tuesday, February 2,1960 Egyptian Troops Delegation M ay Represent Reported Moving " J 1 To Israeli Border Ukraine at UN Convention JERUSALEM, Israeli Sector (UPI) Isreal and the United Arab * Eleven delegates and six alter senior from Newton, Kansas; Republic exchanged threats of war nates have been chosen to attend Rosalie Morgenweck, senior from yesterday following sporadic troop the tenth annual Model United Na Kelso, Wash.; Gary Morrow, soph clashes along the Syrian frontier. tions Convention in San'Francisco omore from Baker; Ed Risse, senior April 6 to 9, according to Kemal In Cairo, the Egyptian govern- i senior from West Glacier and Da ment declared a state of emer Karpat, assistant professor of poli vid Voight, freshman froto tical science. -

BCN 205 Woodland Park No.261 Georgetown, TX 78633 September-October 2011

BCN 205 Woodland Park no.261 Georgetown, TX 78633 september-october 2011 FIRST CLASS MAIL Olde Prints BCN on the web at www.boxingcollectors.com The number on your label is the last issue of your subscription PLEASE VISIT OUR WEBSITE AT WWW.HEAVYWEIGHTCOLLECTIBLES.COM FOR RARE, HARD-TO-FIND BOXING ITEMS SUCH AS, POSTERS, AUTOGRAPHS, VINTAGE PHOTOS, MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS, ETC. WE ARE ALWAYS LOOKING TO PURCHASE UNIQUE ITEMS. PLEASE CONTACT LOU MANFRA AT 718-979-9556 OR EMAIL US AT [email protected] 16 1 JO SPORTS, INC. BOXING SALE Les Wolff, LLC 20 Muhammad Ali Complete Sports Illustrated 35th Anniver- VISIT OUR WEBSITE: sary from 1989 autographed on the cover Muhammad Ali www.josportsinc.com Memorabilia and Cassius Clay underneath. Recent autographs. Beautiful Thousands Of Boxing Items For Sale! autographs. $500 BOXING ITEMS FOR SALE: 21 Muhammad Ali/Ken Norton 9/28/76 MSG Full Unused 1. MUHAMMAD ALI EXHIBITION PROGRAM: 1 Jack Johnson 8”x10” BxW photo autographed while Cham- Ticket to there Fight autographed $750 8/24/1972, Baltimore, VG-EX, RARE-Not Seen Be- pion Rare Boxing pose with PSA and JSA plus LWA letters. 22 Muhammad Ali vs. Lyle Alzado fi ght program for there exhi- fore.$800.00 True one of a kind and only the second one I have ever had in bition fi ght $150 2. ALI-LISTON II PRESS KIT: 5/25/1965, Championship boxing pose. $7,500 23 Muhammad Ali vs. Ken Norton 9/28/76 Yankee Stadium Rematch, EX.$350.00 2 Jack Johnson 3x5 paper autographed in pencil yours truly program $125 3. -

Congressional Record—Senate S1609

February 27, 2001 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S1609 professional bouts to Montana, including across the United States through the February 24, 1996, is to continue in ef- three world championship fights. As chair- Paralyzed Veterans of America. The fect beyond March 1, 2001. man of the Commission, he promoted the walk-a-thon occurred over several GEORGE W. BUSH. Gene Fullmer-Joey Giardello Middleweight school days, where the children walked THE WHITE HOUSE, February 27, 2001. Championship of the World title match on April 29, 1960, in Bozeman. during breaks during the school day. f Basements and gyms all over Billings and Some children even sacrificed their Laurel were the sites for years to come as lunches and walked in the rain and REPORT ON THE PROPOSED BUDG- Sonny trained young fighters. He estimated cold weather just to raise a few more ET FOR THE UNITED STATES OF that he helped develop 2,500–3,000 fighters dollars. AMERICA—MESSAGE FROM THE during those years. These fine young Americans set a PRESIDENT—PM 8 The Student Council of Eastern Montana wonderful example to men, women, and The PRESIDING OFFICER laid be- College, now Montana State University-Bil- children everywhere. With a little ini- lings, originated the annual Sonny O’Day fore the Senate the following message Smoker, a fund raiser that entertained the tiative and a lot of heart, the fifth from the President of the United greater Billings area from 1975–81. graders at Shoemaker School were able States, together with an accompanying Sonny’s civic community service included to help paralyzed veterans throughout report; which was ordered to lie on the 30 years as a Kiwanian, including service as our great Nation. -

Tratarán Deconcertar Revancha De Carlos Ortiz Y Johnny Busso

Pág. 6 -MAMO US AMERICA* »¦ m* Logar! Subió Tratarán de Concertar Revancha al Ring Como de Carlos Ortiz y Johnny Busso el Favorito HOLLYWOOD, julio 2—(UPI)— El cubano Isaac Logart, primero en la clasificación de peso welter LOS LIDERES Al BATE EN LAS GRANDES LIGAS i Revela Club Internacional de Boxeo de la revista The Ring, figuraba co LIGA r ,/'IONAL mo favorito en proporción de dos Pronósito de Firmar Nuevo Combate a uno para su pelea en esta noche J. V. C. H. Ave. contra el excampeón de peso livia- NUEVA YORK, (UPI)—Lo con- no de California Dan Jordán. MAYS, San Francisco 60 279 57 103 369 tendientes peso ligero oJhnny Bus Logart subirá al ring con 52 vic- Musial, San Luis '64 234 36 84 359 so y Carlos Ortiz probablemente torias. ocho derrotas y cinco empa- Dark, Chicago 54 219 25 74 338 serán firmados para una pelea de tes, después de haber superado a figuras como el Gaspar Ashburn, Filadelfia 66 259 40 87 336 revancha en el Madison Square mexicano el ó el 29 de agosto de- Ortega. Gil Turner, Joe Miceli, Crowe, Cincinnati 49 161 16 54 335 Garden 22 bido al debatido triunfo por deci- Walt Byers, Yama Bahama y Vir- Floods, San Luis 50 22 51 155 329 sión dividida de Busso el viernes gil Akins; este último actualmente Green, San Luis .......... 60 194 28 63 325 por la noche, que rompió el invic- titular de la división. to al puertorriqueño Ortiz. Akins vengó su derrota en la re- LIGA AMERICANA El que una lesión en la mano ciente pelea del torneo de elimina- J. -

Theboxing Biographies Newsletter Volume3 - No 11 25Th Dec, 2008

1 TheBoxing Biographies Newsletter Volume3 - No 11 25th DEc, 2008 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to receive future newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] The newsletter is also available as a word doc on request As always the full versions of these articles are on the website My very best wishes to all my readers and thank you for the continued support you have given which I do appreciate a great deal. Name: Willie Pastrano Career Record: click Birth Name: Wilfred Raleigh Pastrano Nationality: US American Hometown: New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Born: 1935-11-27 Died: 1997-12-06 Age at Death: 62 Stance: Orthodox Height: 6′ 0″ Trainers: Angelo Dundee & Whitey Esneault Manager: Whitey Esneault Wilfred Raleigh Pastrano was born in the Vieux Carrê district of New Orleans, Louisiana, on 27 November 1935. He had a hard upbringing, under the gaze of a strict father who threatened him with the belt if he caught him backing off from a confrontation. 'I used to run from fights,' he told American writer Peter Heller in 1970. 'And papa would see it from the steps. He'd take his belt, he'd say "All right, me or him?" and I'd go beat the kid: His father worked wherever and whenever he could, in shipyards and factories, sometimes as a welder, sometimes as a carpenter. 'I remember nine dollars a week paychecks,' the youngster recalled. 'Me, my mother, my step-brother, and my father and whatever hangers-on there were...there were always floaters in the family.' Pastrano was an overweight child but, like millions of youngsters at the time, he wanted to be a sports star like baseball's Babe Ruth. -

The EXPONENT, He Had This to Say: MSC

tend the Sunrise MSC Rodeo ervice, Danforth THE Friday and Saturday ,hapel-6:30 a.m. Exponent Evening - 8:00 Ea ster Sunday of montana state college Fieldhouse TIIE MONTANA EXPONENT F rid ay, April 20. I 962 Spring Roundtable Set for May 21; Wages Discussed Tom Richardson, AS~fSC presi dent, informed Senate Monday that the spring quarter Presi dent's Rouncltable discussion will be held May 21. At thjs meeting President Renne and members of the staff will discuss topics of interest to the student body. Sug gestions for discussion should be turned in to Bob Morgan. steer ing committee chairman, for con· sideration. Reporting from steering com mittee, Bob Morgan recommended that salaries be designated for the offices of senate secretary and ASMSC vice president. Senate approved a motion to suggest a salary of $100 annually for the secretary and $250 annually for the vice president for the approval of the student body at an election ED HARPER DON WOLFE next fall quarter. It was also de cided to abolish the tradition of holding an all-school dance with the understanding that the money from thjs project will be budgeted for by the Lectures and Concerts .larper; Wolf Top ASMSC Election Committee to help improve their program. By RONALD WALTON Commissioner of F o r en s i c s, Ed Harper polled 831 votes to Wess Anderson's 684 to win the Student Body Presidency last Tuesday. Don Wolfe Jack Dunn, presented a re\>;ew of 9) won OYer Tom Fay (312). the District High School Speech . -

Fight Year Duration (Mins)

Fight Year Duration (mins) 1921 Jack Dempsey vs Georges Carpentier (23:10) 1921 23 1932 Max Schmeling vs Mickey Walker (23:17) 1932 23 1933 Primo Carnera vs Jack Sharkey-II (23:15) 1933 23 1933 Max Schmeling vs Max Baer (23:18) 1933 23 1934 Max Baer vs Primo Carnera (24:19) 1934 25 1936 Tony Canzoneri vs Jimmy McLarnin (19:11) 1936 20 1938 James J. Braddock vs Tommy Farr (20:00) 1938 20 1940 Joe Louis vs Arturo Godoy-I (23:09) 1940 23 1940 Max Baer vs Pat Comiskey (10:06) – 15 min 1940 10 1940 Max Baer vs Tony Galento (20:48) 1940 21 1941 Joe Louis vs Billy Conn-I (23:46) 1941 24 1946 Joe Louis vs Billy Conn-II (21:48) 1946 22 1950 Joe Louis vs Ezzard Charles (1:04:45) - 1HR 1950 65 version also available 1950 Sandy Saddler vs Charley Riley (47:21) 1950 47 1951 Rocky Marciano vs Rex Layne (17:10) 1951 17 1951 Joe Louis vs Rocky Marciano (23:55) 1951 24 1951 Kid Gavilan vs Billy Graham-III (47:34) 1951 48 1951 Sugar Ray Robinson vs Jake LaMotta-VI (47:30) 1951 47 1951 Harry “Kid” Matthews vs Danny Nardico (40:00) 1951 40 1951 Harry Matthews vs Bob Murphy (23:11) 1951 23 1951 Joe Louis vs Cesar Brion (43:32) 1951 44 1951 Joey Maxim vs Bob Murphy (47:07) 1951 47 1951 Ezzard Charles vs Joe Walcott-II & III (21:45) 1951 21 1951 Archie Moore vs Jimmy Bivins-V (22:48) 1951 23 1951 Sugar Ray Robinson vs Randy Turpin-II (19:48) 1951 20 1952 Billy Graham vs Joey Giardello-II (22:53) 1952 23 1952 Jake LaMotta vs Eugene Hairston-II (41:15) 1952 41 1952 Rocky Graziano vs Chuck Davey (45:30) 1952 46 1952 Rocky Marciano vs Joe Walcott-I (47:13) 1952