Paternalism and Segregation of Colonial Williamsburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Howard Lineage

The Howard Lineage The Ancestry of IDA ANN BOYDSTUN WELCH Through Her Mother EoLINE FRANCES How.ARD BOYDSTUN By GUSTINE COURSON WEA VER (Mrs. Clifford Selden Weaver) POWELL AND WHITE CINCINNATI, OHIO Copyright, 1929. MRS. EDWARD S. WELCH Shenandoah, Iowa Printed in United States of America EoLINE FRANCES HowARD BoYDSTUN Other Books by Mrs. Clifford Weaver The House That A lap Built Our Guest The Minister's Wife Hop Run The Boydstun Family The Gustine Compendium DEDICATION This book is lovingly dedicated to the memory of my Dear Mother, Eoline Frances Howard Boydstun. As I turn the last pages of this manuscript, I am seated in my summer home, Echo Lodge at Mercer, Wisconsin. Here my sainted Mother loved to sojourn with us. Through a long period of lustrous summer days did we thus abide here together beneath these virgin pine and spruce trees by the side of Echo Lake. Today her love is the most radiant gift I have in my casket of Zif e's memories. Elta Olive Boydstun Young, (the wife of Clifford Young) , my sister, is with me as I pen these words of dedica tion; therefore, I wish to include her in these lines of love. Our brother, -Charles Terrel Boydstun, would were he present with us at this moment, wish to be included in this dedicatory page; hence, I pen his name also. Signed by me, this fifteenth day of August, 1928, Echo Lodge, Mercer, Wisconsin. · Ida Ann Boydstun Welch, ( the ivife of Edward Samuel Welch). FOREWORD The author offers these pages more in the form of out lines than as finished genealogies on the many illustrious lines which are included in the lineage of her beloved Aunt, EOLINE FRANCES HOW ARD BOYDSTUN It is the author's fond hope that her findings, all of which have been classified under each surname may prove of value to unborn descendants who may, perchance, take up the threads and weave from them a more glorious tapestry than that which she was able to accomplish. -

“Lafayette in Williamsburg” (Walking Tour)

Other Sites to Visit • African American Religion exhibit– Explore the religious heritage of Africans and their Virginia descendants. Lafayette in • American Indian Interpretation– Explore the diverse cultures of Native peoples striving to preserve their traditional way of life and learn about the roles they played in creating a new country. Williamsburg • Apothecary – Learn how medicine, wellness, and surgical practices of the 18th century compare to today. • Cabinetmaker & Harpsichord Maker – Watch expert woodworkers fashion the intricate details of luxury products with period hand tools. AMERICAN FRIENDS OF LAFAYETTE • Capitol – Take a guided tour of the first floor entering through the Courtroom and exiting through the House of Burgesses. Annual Meeting 2021 June 13, 2021 • Carpenter’s Yard – Discover how the carpenters use hand tools to transform trees into lumber and lumber into buildings. • Courthouse – Experience justice in the 18th century in an original building. • Gunsmith – See how rifles, pistols, and fowling pieces are made using the tools and techniques of the 18th-century. • Joinery – Watch our experts use saws, planes, hammers, and other tools to fashion wood into the pieces of a future building. • Milliner & Mantua-maker – Shop for latest hats, headwear, ornaments, and accessories. Watch as old gowns are updated to the newest 18th-century fashion. • Tailor – Touch and feel the many different sorts of fabrics and garments that clothed colonial Americans, from elegant suits in the latest London styles to the sturdy uniforms of Revolutionary soldiers. • Public Leather Works – Discover how workman cut, mold, and stitch leather and heavy textiles. • Printing Office & Bindery – Watch and learn as printers set type and use reproduction printing presses to manufacture colonial newspapers, political notices, pamphlets, and books. -

Williamsburg Reserve Collection Celebrating the Orgin of American Style

“So that the future may learn from the past.” — John d. rockefeller, Jr. 108 williamsburg reserve collection Celebrating the Orgin of American Style. 131109 colonial williamsburg Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg, the capital of the colony of Virginia, owed its inception to politics, its design to human ingenuity, and its prosperity to government, commerce and war. Though never larger in size than a small English country town, Virginia’s metropolis became Virginia’s center of imperial rule, transatlantic trade, enlightened ideas and genteel fashion. Williamsburg served the populace of the surrounding colonies as a marketplace for goods and services, as a legal, administrative and religious center, and as a resort for shopping,information and diversion. But the capital was also a complex urban community with its own patterns of work, family life and cultural activities. Within Williamsburg’s year round populations, a rich tapestry of personal, familial, work, social, racial, gender and cultural relationships could be found. In Williamsburg patriots such as Patrick Henry protested parliamentary taxation by asserting their right as freeborn Englishmen to be taxed only by representatives of their own choosing. When British authorities reasserted their parliamentary sovereign right to tax the King’s subjects wherever they reside, Thomas Jefferson, George Mason, James Madison, George Washington and other Virginians claimed their right to govern themselves by virtue of their honesty and the logic of common sense. Many other Americans joined these Virginians in defending their countrymen’s liberties against what they came to regard as British tyranny. They fought for and won their independence. And they then fashioned governments and institutions of self-rule, many of which guide our lives today. -

New Membership Program Offers Value and Supports the Growing Art

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation P.O. Box 1776 Williamsburg, Va. 23187-1776 www.colonialwilliamsburg.com New Membership Program Offers Value and Supports the Growing Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg Individual and family memberships offer value and benefits and support the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum “Dude,” tobacconist figure ca. 1880, museum purchase, Winthrop Rockefeller, part of the exhibition “Sidewalks to Rooftops: Outdoor Folk Art” at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum; rendering of the South Nassau Street entrance to the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg; “Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I”, artist unidentified, 1590-1600, gift of Preston Davie, part of the exhibition “British Masterworks: Ninety Years of Collecting at Colonial Williamsburg,” opening Feb. 15 at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum. WILLIAMSBURG, Va. (Feb. 5, 2019) –Colonial Williamsburg offers a new opportunity to enjoy and support its world-class art museums, the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, with annual individual and family memberships that provide guest benefits and advance both institutions’ exhibition and interpretation of America’s shared history. The DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, which showcases the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670-1840, and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, home to the nation’s premier collection of American folk art, remain open during their donor-funded, $41.7-million expansion, which broke ground in 2017 and is scheduled for completion this year. Once completed, the expansion will add 65,000 square feet with a 22- percent increase in exhibition space as well as a new visitor-friendly entrance on Nassau Street. -

Fire Alarm Newsletter February Issue of the Journal of Operations Management, Vol

William and Mary Faculty Meeting Set To: All Members of the Faculty and Administration SUBJECT: College-wide Faculty Meeting The Annual College-wide Faculty Meeting will be held on Tuesday, September 4, 1984, in Millington Auditorium at 3:30 p.m. On that occasion we shall be introducing new members of the Faculty of the College to their colleagues. Deans and Department Chairmen are invited to extend special invitations to their new colleagues to attend this meeting. NEWS A listing of new members of the Faculty will be distributed in advance Tuesday, April 24, 1984 Permit No. 26 of the meeting, containing brief biographical and professional informa¬ Volume XII, Number 28 Non-Profit Organization tion about each individual, to reduce the time of introductions. Mr. U.S. Postage PAID at Williamsburg, Va. George R. Healy, as Provost of the College, will introduce all new mem¬ bers of the Faculty. The meeting, which should be over by 4:30 p.m., will be followed by an informal reception in Andrews Hall Foyer, to which you are all invited. I look forward to seeing you on Tuesday, September 4. Social Psychiatrist Robert Coles Zoe and I also look forward to welcoming you to the President's House for an informal brunch on Sunday, September 9, at 12:30 p.m. Next On Cosmos Lecture Series I will be sending you another notice later in the summer, but 1 hope you will place this important meeting on your calendars now. The "Our Future in the Cosmos" lec¬ ture series, co-sponsored by the College and NASA, since 1974 anues this spring with the appearance of Dr. -

Professorship Honors Brooks George Fellowship in Law and Public

Non-Profit Organiution U.S. Pctage PAID it WBlianuburg, VA Permit No. 26 William and Mary NEWS A WEEKLY NEWSPAPER PUBLISHED FOR AND ABOUT THE FACULTY, STUDENTS AND STAFF OF THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY Volume XVin, Number 21 Wednesday, February 22,1989 Signet Banking Corp. pledges $200,000 im Professorship honors Brooks George Signet Banking Corporation has pledged George was amemberof the William andMary $200,000 to the College to establish the W. Brooks Board of Visitors from 1958 to 1968 and served as Timely reminders George Professorship of Business Administra¬ Rector of the CoUege from 1966 to 1968. In 1956, tion. he served as president of the Society of the No News during break The announcement was made by Frederick Alumni. There will be no issue of The William and Mary Deane Jr., chairman and CEO of the $11 billion He is trustee emeritus of the university's En¬ bank holding company headquartered in Rich¬ News during Spring Break, March 3-13. Notices dowment Association and chairman emeritus of mond. of events during the first half of March should be the board of the School of Business Administra¬ included in the March 1 issue. Deadline for that Income from the endowment will qualify for tion Sponsors Inc., a group which he founded. He issue is 5 p.m., Friday, Feb. 24. matching funds under Virginia's Eminent Schol¬ received the Alumni Medallion in 1954 for service ars Program. and loyalty to his alma mater. Art and Power Signet's commitment honors W. Brooks Anative of Stuart, Va., George began his career Moni Adams, research associate in African George '32 of Richmond, who has given many with Larus & Brother Co. -

The Premier Luxury Destination Management Company for the U.S., Canada and the Caribbean

THE PREMIER LUXURY DESTINATION MANAGEMENT COMPANY FOR THE U.S., CANADA AND THE CARIBBEAN 2 3 CONTENTS ABOUT US Our Story 5 Why Excursionist? 7 What We Offer 7 TRAVEL STYLES Luxury Family Travel 13 Romance Travel 14 Corporate Travel 15 Educational Travel 16 Festival + Event Travel 18 TRAVEL BY PASSION Food + Drink 21 The Arts 22 People + Culture 23 Nature 24 Wellness 25 Sports + Adventure 26 THE REGIONS New England 28 New York State 32 The Mid-Atlantic 36 The South 40 Florida 44 The Southwest 48 The West 52 The Pacific Northwest 56 California 60 Alaska 64 Hawaii 68 Western Canada 72 Eastern Canada 76 The Caribbean 80 HOTELS + MAPS Hotel Collection 84 Maps 94 3 “Our mission is to empower luxury travelers — whether a couple, family, or corporate group — to live out their diverse passions through exceptional, life-changing experiences that we design and deliver.” 4 Our Story Excursionist was founded in 2010 by three friends who immigrated to North America from various corners of the world and developed a dedication to sharing this continent’s rich history, nature, cuisine and culture with others. Identifying a gap in the marketplace for a true luxury-focused destination management company for the United States, Canada and the Caribbean, we have built an organization that not only has geographical breadth across our territory, but also an intense depth of local knowledge in each destination where we work. We achieve this by bringing to bear our diverse expertise in the industry, as well as our personal relationships in the sciences, arts, education, government and business. -

Nomination Form

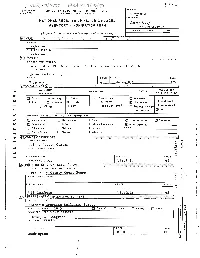

I[]ExceIl_3. Fair 0.leriom.d Ruin. U-~wd CONDITION I (Check Onel I (Check One) I Altered Un0lt.r.d I n Mowed hipinol Sin OR!CINAL (IILnoanJ PHIIfCAL APPEARLNCE Powhatan is a classic two-story Virginia mansion of the Early Georgian period. The>rectangular structure is five bays long by two bays deep, with centered doors on front and rear. Its brickwork exhibits the highest standards of Colonial craftsmanship. The walls are laid in Flemish bond with glazed headers above the bevelled water table with English bond below. Rubbed work appears at the corners, window and door jambs, and belt course, while gauged work appears in the splayed flat arches over the windows and doors. The basement windows are topped by gauged segmental arches. The two massive interior end T-shaped chimneys are finely execute4 but are relatively late examples of their form. The chimney caps are both corbelled and gauged. ~eciusethe hbuse was gutted bi fire, none but the masonry members are I I original. Nearly all the evidences of.the post-fire rebuilding were m removed during a thorough renwation in 1948. As part of the renovation, rn the hipped roof was replaced following the lines of the original roof as indicated by scars in the chimneys. The roof is pierced by dormer rn windows which may or my not have bean an original feature, The Early - Georgian style sash, sills, architraves, and modillion cornice also date z from the renovation. While nearly all the interior woodwork dates from m 1948, the double pile plan with central hall survives. -

Natioflb! HISTORIC LANDMARKS Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR ^^TAT"E (Rev

THEME: ^fch:chitecture NATIOflB! HISTORIC LANDMARKS Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ^^TAT"E (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE VirjVirginia COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES James City AT; °;-' T; J"" Bil$VENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) COMMON: Carter's Grove Plantation AND/OR HISTORIC: Carter's Grove Plantation STREET AND NUMBER: Route 60, James City County CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: vicinity of Williamsburg 001 COUNTY: Virginia 51 James City 095 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District gg Building d Public Public Acquisition: K Occupied Yes: i iii . j I I Restricted Site Q Structure 18 Private || In Process LJ Unoccupied ' ' i i r> . i 6*k Unrestricted D Object D Both | | Being 'Considered D Preservation work lc* in progress ' 1 PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) 53 Agricultural [ | Government | | Park Transportation S Comments [~| Commercial I I Industrial |X[ Private Residence Q Other ....___.,, The _____________kitchen D Educotionai D Military rj Religious dependency is occupied by Mr. & D Entertainment D Museum rj Scientific Mrs. McGinley. The rest of the ' WiK«-¥.:.:jliBi.; ;ttjr: the" pub^li;^! OWNER'S NAME: Colonial Williamsburg, Inc., Carlisle H. Humelsine, President Virginia STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: CODF Williamsburg Virginia 51 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC: Clerk of the Circuit Court P.O. Box 385 CityJames STREET AND NUMBER: Court Street (2 blocks south of -

Chapter 2 Yeardley's Fort (44Pg65)

CHAPTER 2 YEARDLEY'S FORT (44PG65) INTRODUCTION In this chapter the fort and administrative center of Flowerdew at 44PG65 are examined in relation to town and fortification planning and the cultural behavior so displayed (Barka 1975, Brain et al. 1976, Carson et al. 1981; Barka 1993; Hodges 1987, 1992a, 1992b, 1993; Deetz 1993). To develop this information, we present the historical data pertaining to town development and documented fortification initiatives as a key part of an overall descriptive grid to exploit the ambiguity of the site phenomena and the historic record. We are not just using historic documents to perform a validation of archaeological hypotheses; rather, we are trying to understand how small-scale variant planning models evolved regionally in a trajectory away from mainstream planning ideals (Beaudry 1988:1). This helps refine our perceptions of this site. The analysis then turns to close examination of design components at the archaeological site that might reveal evidence of competence or "mental template." These are then also factored into a more balanced and meaningful cultural interpretation of the site. 58 59 The site is used to develop baseline explanatory models that are considered in a broader, multi-site context in Chapter 3. Therefore, this section will detail more robust working interpretations that help lay the foundations for the direction of the entire study. In short, learning more about this site as a representative example of an Anglo-Dutch fort/English farmstead teaches us more about many sites struggling with the same practical constraints and planning ideals that Garvan (1951) and Reps (1972) defined. -

1 2 3 4 5 a Brief Guide to Bruton Parish Church

A BRIEF GUIDE TO BRUTON PARISH CHURCH (1) THE TOWER: The Tower was added to the church in 1769 and 1 houses the historic Tarpley Bell, given to Bruton Parish in 1761. It continues to summon worshippers every day. Inside the doorway of the Tower is a bronze bust of the Reverend W.A.R. Goodwin, rector, 1903-1909 and 1926-1938. (2) THE WEST GALLERY: Erected for The College of William and Mary students and the only original part of the interior, this gallery has a handrail with visible initials carved nearly 300 years ago. (3) THE HIGH BOX PEWS: These pews with doors were typical of unheated eighteenth-century English churches. Names on the doors 2 commemorate parish leaders and well-known patriots who worshipped here as college students or members of the colonial General Assembly. Names such as Patrick Henry, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe and John Marshall remind us of the important place of Bruton Parish in colonial and early U.S. history. (4) THE GOVERNOR’S PEW: Reserved for the royal governor and Council members, 3 this pew has an ornate canopied chair. In colonial days it had curtains for privacy and warmth. Church wardens and vestrymen occupied the pews nearer the altar. Today, the choir uses them. (5) THE BRONZE LECTERN: In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt presented the lectern to Bruton to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the first permanent English settlement and the establishment of the Anglican church at Jamestown. Near the lectern are the 4 gravestones of royal Governor Francis Fauquier and patriot Edmund Pendleton. -

Regional Map

REGIONAL MAP N e w K e n t G ll o u c e s t e r ñðò11 James City County, Williamsburg, York County York Chesapeake River Bay ¤£17 (!30 (!30 15 ñðò 5 n CAMP PEARY Æc 4 2 R ! O CHA MBE AU D R 64 RD ND § O ¨¦ M ICH R Y K P E 60 IN S D L 60 R ¤£ E D M ON U ¤£ H M ICH R 25 199 5 1 8 E R 5 ! OCH (! AM B ^ n EAU ^ DR CHEATHAM 3 ñðò 31 3 "11 n ANNEX 4 ^ 2^ " ^ USCG 9 ST " LLARD ñ 3 BA TRAINING C 6 O 3 O ! K CENTER 19 R ^ D YORKTOWN 64 ñðò 2 ¨¦§ v® 17 2 17 ¤£ GOO 15 SLEY RD 173 ñðò n !n6 (! G 238 E O 3 R (! G 19 E ¹º W RIC A H S G n M O H O ND I O R N D D G W 143 CHEATHAM T O IN 3 N ! M N ( E ANNEX EM C O K n R R YORKTOWN IA D 6 L H NAVAL ñðò WY D 21 WEAPONS R G 610 R ñðò U n 14 9 STATION B Æc 1 (! S M 1 Poquoson C A 132 A I 11 River 614 P L " ñðò I n L ! T I ( O W ñðò (! L L D A L 14 2 N 10 2 O 3 D " 4 1 " I N 16 E Y G n T K ^ R P U 64 J a m e s D O J a m e s R 17 7 R ñðò ¨¦§ E T ¤£ N 5 E " ñðò C ii t y C H U S 10 M 8 I EL U ! S Q IN 30 E R P n A 620 K 8 W M " Y Y P o q u o s o n K (! P o q u o s o n W n P n SEC E ON D ST N P I A S R 60 G L IC E 4 E n H M M RD S ! U £ T O S ¤ H 13 S 24 ND PA 1 R BY 16 27 D R E ñðò ^ Æc ñðò A n M Y ñðò n n P 199 5 W YO G K R ! E ñðò K S O T P 1 (! 64 R M " 105 G E ER E N R 13 I IM ¨¦§ W A S (! A C S L 1 TR H E v® L IN PO 173 M C n G N AHO T U N D TAS V O H H 6 23 TRL L (! N 12 E B M 17 6 N 9 E ! R IS " " M 171 Y T O n S R S ñðò E Æc U IA T (! ñðò E L V A T H R W O O Y W L F Y L 7 D 2 E V T ! L H C 3 I B E 29 T 14 C N H 2 1 G n R O ñ M I ER E M RI B ^ MAC E TR N n ¹º L E K D R 60 64 D 1 ¤£ 7 2 1 26 ×× ¨¦§ D LV