Celebrating 50 Years: 1970

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pft Pittsburgh Picks! Aft Convention 2018

Pittsburgh Federation of Teachers PFT PITTSBURGH PICKS! AFT CONVENTION 2018 Welcome to Pittsburgh! The “Front Door” you see above is just a glimpse of what awaits you in the Steel City during our national convention! Here are some of our members’ absolute favorites – from restaurants and tours, to the best views, shopping, sights, and places to see, and be seen! Sightseeing, Tours & Seeing The City Double Decker Bus Just Ducky Tours Online booking only Land and Water Tour of the ‘Burgh Neighborhood and City Points of Interest Tours 125 W. Station Square Drive (15219) Taste of Pittsburgh Tours Gateway Clipper Tours Online booking only Tour the Beautiful Three Rivers Walking & Tasting Tours of City Neighborhoods 350 W. Station Square Drive (15219) Pittsburgh Party Pedaler Rivers of Steel Pedal Pittsburgh – Drink and Don’t Drive! Classic Boat Tour 2524 Penn Avenue (15222) Rivers of Steel Dock (15212) City Brew Tours Beer Lovers: Drink and Don’t Drive! 112 Washington Place (15219) Culture, Museums, and Theatres Andy Warhol Museum Pittsburgh Zoo 117 Sandusky Street (15212) 7370 Baker Street (15206) Mattress Factory The Frick Museum 500 Sampsonia Way (15212) 7227 Reynolds Street (15208) Randyland Fallingwater 1501 Arch Street (15212) Mill Run, PA (15464) National Aviary Flight 93 National Memorial 700 Arch Street (15212) 6424 Lincoln Highway (15563) Phipps Conservatory Pgh CLO (Civic Light Opera) 1 Schenley Drive (15213) 719 Liberty Avenue 6th Fl (15222) Carnegie Museum Arcade Comedy Theater 4400 Forbes Avenue (15213) 943 Penn Avenue (15222) -

Competitive Programs

DVRPC FY2017 TIP FOR PENNSYLVANIA CHAPTER 7: COMPETITIVE PROGRAMS This section contains lists of projects that have been awarded via regional or statewide competitive programs, which are open to a specialized segment of the public. As projects move through the delivery pipeline, they may or may not show up in the active TIP project listings, but are important to the DVRPC region for demonstrating investments in particular types of infrastructure and potential fund sources. REGIONAL COMPETITIVE PROGRAMS Competitive Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) Program – DVRPC periodically sets aside a specific amount of CMAQ funds for a DVRPC Competitive CMAQ Program (see MPMS #48201), which seeks transportation-related projects that can help the region reduce emissions from mobile sources and meet the National Clean Air Act Standards. CMAQ-eligible projects will demonstrably reduce air pollution emissions and, in many cases, reduce traffic congestion. Projects may be submitted by a public agency or a public-private partnership. A Subcommittee of the DVRPC Regional Technical Committee (RTC) evaluates the projects and makes recommendations to the DVRPC Board for final selection. In July 2016, the DVRPC Board approved the most recent round of the DVRPC Competitive CMAQ Program by selecting 17 projects for funding in the DVRPC Pennsylvania counties, for a total CMAQ award of $21,900,000. For more information, see www.dvrpc.org/CMAQ/ Regional Trails Program (Phases 1-4) – The Regional Trails Program, administered by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, with funding from the William Penn Foundation, aims to capitalize upon opportunities for trail development by providing funding for targeted, priority trail design, construction, and planning projects that will promote a truly connected, regional network of multiuse trails with Philadelphia and Camden as its hub. -

Governor's Advisory Commission on Postsecondary Education

Governor’s Advisory Commission on Postsecondary Education: REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS November 14, 2012 Letter from the Commission Pennsylvania has long been recognized for offering abundant and diverse opportunities for postsecondary education. Our tremendous asset includes the universities of the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education, the state-related universities, the community colleges, private colleges and universities, research and graduate institutions, adult education and family literacy providers, private licensed schools, proprietary institutions, specialized associate degree-granting institutions and business, trade, and technical schools that offer vocational programs. The Governor‘s charge was to create a multi-year framework that would sustain and enhance the commonwealth‘s postsecondary education system, while serving the needs of students and employers for the 21st century. During the course of our discussions, we pondered questions such as: What types of collaborations will be needed within the next 5-10 years to meet Pennsylvania‘s labor demands, to achieve sector efficiencies and to increase accessibility and affordability for all users? What role should government and state policymakers play in helping achieve these goals? What best practices exist regionally, nationally and globally that could be held as standards for replication? What strategies would be needed to overcome potential barriers that could stand in the way of making these changes? We deliberated as a commission and listened to members of the public and expert speakers from all regions of the commonwealth. We clearly heard the call for businesses, government and education providers to collectively meet the needs of lifelong learners, increase student readiness, improve business/education partnerships, provide greater accountability to commonwealth taxpayers and users of the system, increase flexibility in delivery and provide strategic financial investments based on performance. -

PPFF Spring2020 Nwsltr.Qxd

Penn’s Stewards News from the Pennsylvania Parks & Forests Foundation Spring 2020 CLIMATE CHANGE Managing Pennsylvania’s Greatest Environmental Crisis rt e ilb By Greg Czarnecki, G y Tuscarora se Ka it: Director, Applied Climate Science, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources red State Park o C Phot INTHIS ISSUE In the 50 years since the first Earth Day we have made tremendous PG: 1 Climate Change progress protecting our air, water, and natural resources. But in spite PG: 2 President’s Message A Call for Advocates of that progress we now face our greatest environmental crisis— PG: 3-4 Climate Change continued climate change. PG: 4 Happy 50th Birthday Earth Day Nearly every day we hear stories about the effects of climate change, such as PG: 5 The Value of Trees melting glaciers in Greenland, horrific wildfires in Australia and California, and super- PG: 6 Let There Be Trees on Earth charged hurricanes. While many of these events are far away, we are also seeing climate PG: 7 Wilderness Wheels change impacts here in Pennsylvania. continued on page 3 Skill Builder PG: 8 We Will Miss Flooding at the Presque Isle Marina due to heavy lake levels. New Faces at PPFF PG: 9 Calendar of Events #PAFacesofRec Bring on Spring PG: 10 PPFF Friends Groups Your Friends in Action PG: 11 More Friends in Action Making an Impact on Legislation PG: 12-13 YOU Made it Happen PG: 14-15 2019 Photo Contest Results PG: 16 Fun Fact! ExtraGive Thank You PPFF Membership Form CONTACT US: Pennsylvania Parks & Forests Foundation 704 Lisburn Road, Suite 102, Camp Hill, PA 17011 (717) 236-7644 www.PaParksAndForests.org Photo Credit: DCNR President’s Message Marci Mowery Happy New Year! By the time this newsletter “...join us in activities lands in your hands, we will be several months r into the new year. -

May-June Newsletter

The Official Publication of the Montour Trail Council MONTOUR TRAIL-LETTER Volume 18 Issue 3 May/June 2007 Cycling to the Function at the For your consideration Junction compiled by Stan Sattinger Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can The Function at the change the world. Indeed, it is the only Junction is only a few days away. thing that ever has. Details regarding the event can be found on the enclosed flyer or you can head to http://www.montourtrail.org/[email protected] Margaret Mead for more details. The purpose of this article is to announce several organized bicycle rides that will culminate at the Function, and several walks that will take place prior to the festivities. One ride begins at Mile 0 near Coraopolis at 10:15 a.m., arriving at the Junction at 12:30 p.m. You can join the ride at the beginning or pick up the ride as it passes by. Contact Dennis Pfeiffer at Inside this issue: 412-762-4857 or [email protected] 2007 Burgh Run 1 Another ride hosted by Dave Wright, [email protected], will start at Walkers Mill Function at the on the Panhandle Trail at 11:00 a.m. arriving at Primrose around 12:30 p.m. Junction The Prez Sez 2 A third ride hosted by Ned Williams, 724-225-9856 or [email protected] ,will begin at 1st Day of Trout Season Joffre, on the newly completed section of the Panhandle and head east to the Function. Contact Ned for Friends Meeting Notices 3 more details. -

Geospatial Analysis: Commuters Access to Transportation Options

Advocacy Sustainability Partnerships Fort Washington Office Park Transportation Demand Management Plan Geospatial Analysis: Commuters Access to Transportation Options Prepared by GVF GVF July 2017 Contents Executive Summary and Key Findings ........................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Sources ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 ArcMap Geocoding and Data Analysis .................................................................................................. 6 Travel Times Analysis ............................................................................................................................ 7 Data Collection .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1. Employee Commuter Survey Results ................................................................................................ 7 2. Office Park Companies Outreach Results ......................................................................................... 7 3. Office Park -

A Smart Choice for a Solid Start: Pre-K Works – So Why Not PA?

A Smart Choice for a Solid Start: Pre-K Works – So Why Not PA? What do Governor Tom Wolf, former governors Tom Corbett, Ed Rendell, Mark Schweiker and more than 130 Democratic and Republican members of the Pennsylvania General Assembly have in common? Give up? They all have been strong supporters of high-quality pre-k for Pennsylvania’s 3- and 4- year olds. Over the past three years, our state policymakers have increased commonwealth support by $90 million to ensure nearly 10,000 additional at-risk children are able to attend a high-quality pre-k classroom. And, this budget season is no different as Governor Wolf has proposed another $40 million increase. Children only have one chance to be preschoolers and benefit from early learning opportunities. They don’t get a do-over when the commonwealth is on better financial ground, or policymakers agree that it’s their turn to be at the top of the budget priority list. Today in Pennsylvania, there are only enough public funds to make high-quality, publicly funded pre-k available to 39 percent of at-risk 3- and 4-year-olds. As a result, many low- income families cannot find or afford high quality pre-k essential to their children's success. A growing body of research has shown that by the age of five, a child’s brain will have reached 90 percent of its adult size with more than one million neural connections forming every second,i but not every child is provided with the stimulating environments and nurturing interactions that can develop those young minds to their fullest potential. -

2018 – 2019 COMMONWEALTH BUDGET These Links May Expire

2018 – 2019 COMMONWEALTH BUDGET These links may expire: July 6 Some telling numbers lie deeper in state education budget The new state education budget officially put into action July 1 has numbers that should make local school administrators a bit happier. Every Luzerne County district saw an increase in combined basic and special education funding, ranging from a 0.1 percent hike for Northwest Area (a... - Wilkes-Barre Times Leader Philadelphia officials fear late addition to state budget could harm health of low-income teens PHILADELPHIA (KYW Newsradio) -- Philadelphia officials are denouncing a provision, tucked into the state budget bill at the last minute, that they say will result in more teenagers getting hooked on tobacco. But there's little they can do about it. As the state's only first class city, Philadelphia has been able to... - KYW State budget has implications for Erie The $32.7 billion spending plan for the 2018-2019 fiscal year boosts funding for education and school safety. June’s passage of a $32.7 billion state spending plan provides more money for education, including school safety, as well as workforce development programs.... - Erie Times- News July 5 Malpractice insurer sues PA for the third time in three years Governor Tom Wolf and legislative leaders are being sued in federal court over a budget provision to fold a medical malpractice insurer and its assets into the state Insurance Department. It’s the latest development in the commonwealth’s repeated attempts to take $200 million from the group’s surplus.... - WHYY Lancaster County schools to receive $3.5M boost in basic education funding in 2018-19 Lancaster County schools in 2018-19 will get nearly $3.5 million more in state basic education funding than last year, under the budget enacted by the governor in June. -

Read This Issue of Perspectives

Issue 5 Perspectives Spring 2021 A newsletter highlighting experiences of our members, partners and volunteers Diversity and Inclusion at WPC: Equity Driven, Community Based, Strategically Focused 2020 was a year like no other. In the drive our mission and work over the next several years,” Tom notes. midst of a worldwide pandemic, The Conservancy’s Director of Community Forestry and TreeVitalize record-setting numbers of wildfires Pittsburgh, Jeff Bergman, leads the Conservancy’s Diversity and and a presidential election, our Inclusion Council and agrees that it is an opportune time to revisit our country learned of and witnessed diversity and inclusion strategic initiative. the horrific events that led to the wrongful and untimely deaths of Working through subcommittees, the council sets priorities focused The Conservancy owns and manages more Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor on attracting more diverse job and internship candidates and seeks than 13,000 acres of land that are open to and George Floyd. opportunities to partner in underserved rural and urban communities. the public, free of charge, for all people to It also helps develop strategies to recruit volunteers from all walks explore, enjoy and be inspired by the natural The aftermath of these beauty of Western Pennsylvania. of life and make Conservancy-owned reserves and Fallingwater unprecedented events rallied a more accessible to all, especially for persons with mobility and other national reckoning to reexamine the causes of and seek an end to physical challenges. racism, bigotry and bias. Black Lives Matter protesters crowded city streets calling for justice, and conversations about race, systematic “It’s important for us to continue this work while learning and racism, diversity, equity and inclusion filled homes, classrooms and understanding the changing boardrooms. -

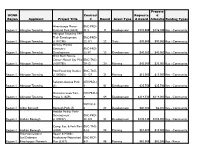

Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste D Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type D Award Allocatio Funding Types

Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste d Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type d Award Allocatio Funding Types Alverthorpe Manor BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township Cultural Park (6422) 11-3 11 Development $223,000 $136,900 Key - Community Abington Township TAP Trail- Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township (1101296) 22-171 22 Trails $90,000 $90,000 Key - Community Ardsley Wildlife Sanctuary- BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township Development 22-37 22 Development $40,000 $40,000 Key - Community Briar Bush Nature Center Master Site Plan BRC-TAG- Region 1 Abington Township (1007785) 20-12 20 Planning $42,000 $37,000 Key - Community Pool Feasibility Studies BRC-TAG- Region 1 Abington Township (1100063) 21-127 21 Planning $15,000 $15,000 Key - Community Rubicam Avenue Park KEY-PRD-1- Region 1 Abington Township (1) 1 01 Development $25,750 $25,700 Key - Community Demonstration Trail - KEY-PRD-4- Region 1 Abington Township Phase I (1659) 4 04 Development $114,330 $114,000 Key - Community KEY-SC-3- Region 1 Aldan Borough Borough Park (5) 6 03 Development $20,000 $2,000 Key - Community Ambler Pocket Park- Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Ambler Borough (1102237) 23-176 23 Development $102,340 $102,000 Key - Community Comp. Rec. & Park Plan BRC-TAG- Region 1 Ambler Borough (4438) 8-16 08 Planning $10,400 $10,000 Key - Community American Littoral Upper & Middle Soc/Delaware Neshaminy Watershed BRC-RCP- Region 1 Riverkeeper Network Plan (3337) 6-9 06 Planning $62,500 $62,500 Key - Rivers Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste d Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type d Award Allocatio Funding Types Valley View Park - Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Aston Township (1100582) 21-114 21 Development $184,000 $164,000 Key - Community Comp. -

Events and Tourism Review

Events and Tourism Review December 2019 Volume 2 No. 2 Understanding Millennials’ Motivations to Visit State Parks: An Exploratory Study Nripendra Singh Clarion University Of Pennsylvania Kristen Kealey Clarion University Of Pennsylvania For Authors Interested in submitting to this journal? We recommend that you review the About the Journal page for the journal's section policies, as well as the Author Guidelines. Authors need to register with the journal prior to submitting or, if already registered, can simply log in and begin the five-step process. For Reviewers If you are interested in serving as a peer reviewer, please register with the journal. Make sure to select that you would like to be contacted to review submissions for this journal. Also, be sure to include your reviewing interests, separated by a comma. About Events and Tourism Review (ETR) ETR aims to advance the delivery of events, tourism and hospitality products and services by stimulating the submission of papers from both industry and academic practitioners and researchers. For more information about ETR visit the Events and Tourism Review. Recommended Citation Singh, N., & Kealey, K. (2019). Understanding Millennials’ Motivations to Visit State Parks: An Exploratory Study. Events and Tourism Review, 2(2), 68-75. Events and Tourism Review Vol. 2 No. 2 (Fall 2019), 68-75, DOI: 10.18060/23259 Copyright © 2019 Nripendra Singh and Kristen Kealey. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribuion 4.0 International License. Singh, N., & Kealey, K. (2019) / Events and Tourism Review, 2(2), 68-75. 69 Abstract State Park’s scenic stretches of flowing rivers and large lakes are popular for canoeing, kayaking, and tubing, but how much of these interests’ millennials are not much explored. -

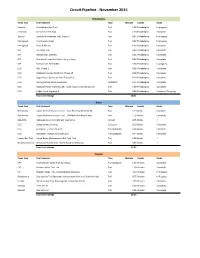

Circuit Pipeline - November 2015

Circuit Pipeline - November 2015 Philadelphia Trunk Trail Trail Segment Type Mileage County Study Cynwyd Parkside Cynwyd Trail Trail 1.50 Philadelphia In progress Cresheim Cresheim Creek Trail Trail 2.20 Philadelphia Complete Tacony Frankford Greenway Trail, Phase 3 Trail 0.84 Philadelphia In progress Pennypack Fox Chase Lorimer Trail 0.42 Philadelphia In progress Pennypack State & Rhawn Trail 0.06 Philadelphia Complete SRT Ivy Ridge Trail Trail 0.60 Philadelphia Complete SRT Wissahickon Gateway Trail 0.31 Philadelphia Complete SRT Boardwalk from Christian to Gray's Ferry Trail 0.42 Philadelphia Complete SRT Bartram's to Fort Mifflin Trail 3.58 Philadelphia In progress ECG K&T, Phase 2 Trail 0.85 Philadelphia Complete ECG Delaware Avenue Extension, Phase 1B Trail 0.28 Philadelphia Complete ECG Sugar House Casino to Penn Treaty Park Trail 0.30 Philadelphia Complete ECG Spring Garden Street Greenway Cycletrack 2.15 Philadelphia Complete ECG Delaware River Trail Sidepath - Washington to Spring Garden Trail 1.90 Philadelphia Complete ECG Cobbs Creek Segment B Trail 0.80 Philadelphia Complete/On-going Total trail mileage 16.21 Bucks Trunk Trail Trail Segment Type Mileage County Study Neshaminy Upper Neshaminy Creek Trail -- Turk Rd to Dark Hollow Rd Trail 6.10 Bucks Complete Neshaminy Upper Neshaminy Creek Trail -- Chalfont/New Britain Gap Trail 1.35 Bucks Complete D&L/ECG Delaware Canal Tunnel (Falls Township) Tunnel 0.05 Bucks ? ECG Bridge Street Crossing Structure 0.10 Bucks Complete ECG Bensalem - Cramer to Birch Trail/Sidepath 0.38 Bucks