This Item Was Submitted to Loughborough's Institutional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Outline and Syllabus the Fab Four and the Stones: How America Surrendered to the Advance Guard of the British Invasion

Course Outline and Syllabus The Fab Four and the Stones: How America surrendered to the advance guard of the British Invasion. This six-week course takes a closer look at the music that inspired these bands, their roots-based influences, and their output of inspired work that was created in the 1960’s. Topics include: The early days, 1960-62: London, Liverpool and Hamburg: Importing rhythm and blues and rockabilly from the States…real rock and roll bands—what a concept! Watch out, world! The heady days of 1963: Don’t look now, but these guys just might be more than great cover bands…and they are becoming very popular…Beatlemania takes off. We can write songs; 1964: the rock and roll band as a creative force. John and Paul, their yin and yang-like personal and musical differences fueling their creative tension, discover that two heads are better than one. The Stones, meanwhile, keep cranking out covers, and plot their conquest of America, one riff at a time. The middle periods, 1965-66: For the boys from Liverpool, waves of brilliant albums that will last forever—every cut a memorable, sing-along winner. While for the Londoners, an artistic breakthrough with their first all--original record. Mick and Keith’s tempestuous relationship pushes away band founder Brian Jones; the Stones are established as a force in the music world. Prisoners of their own success, 1967-68: How their popularity drove them to great heights—and lowered them to awful depths. It’s a long way from three chords and a cloud of dust. -

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

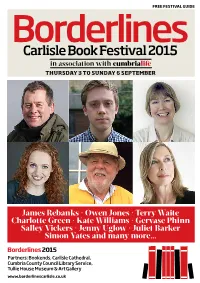

Borderlines 2015

FREE FESTIVAL GUIDE BorderlinesCarlisle Book Festival 2015 in association with cumbrialife THURSDAY 3 TO SUNDAY 6 SEPTEMBER James Rebanks � Owen Jones � Terry Waite Charlotte Green � Kate Williams � Gervase Phinn Salley Vickers � Jenny Uglow � Juliet Barker Simon Yates and many more... Borderlines 2015 Partners: Bookends, Carlisle Cathedral, Cumbria County Council Library Service, Tullie House Museum & Art Gallery www.borderlinescarlisle.co.uk President’s welcome city strolling Rigby Phil Photography The Lanes Carlisle ell done to everyone at The growth in literary festivals in the last image courtesy of BHS Borderlines for making it decade has partly been because the such a resounding reading public, in fact the general public, success, for creating a do like to hear and see real live people for Wliterary festival and making it well and a change, instead of staring at some sort truly a part of the local community, nay, of inanimate box or computer contrap- part of national literary life. It is now so tion. The thing about Borderlines is that well established and embedded that it it is totally locally created and run, a feels as if it has been going for ever, not- for- profit event, from which no one though in fact it only began last year… gets paid. There is a committee of nine yes, only one year ago, so not much to who include representatives from boast about really, but existing- that is an Cumbria County Council, Bookends, achievement in itself. There are now Tullie House and the Cathedral. around 500 annual literary festivals in So keep up the great work. -

Albert Glotzer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1t1n989d No online items Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Processed by Dale Reed. Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Albert Glotzer 91006 1 papers Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Dale Reed Date Completed: 2010 Encoded by: Machine-readable finding aid derived from Microsoft Word and MARC record by Supriya Wronkiewicz. © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Title: Albert Glotzer papers Dates: 1919-1994 Collection Number: 91006 Creator: Glotzer, Albert, 1908-1999 Collection Size: 67 manuscript boxes, 6 envelopes (27.7 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Correspondence, writings, minutes, internal bulletins and other internal party documents, legal documents, and printed matter, relating to Leon Trotsky, the development of American Trotskyism from 1928 until the split in the Socialist Workers Party in 1940, the development of the Workers Party and its successor, the Independent Socialist League, from that time until its merger with the Socialist Party in 1958, Trotskyism abroad, the Dewey Commission hearings of 1937, legal efforts of the Independent Socialist League to secure its removal from the Attorney General's list of subversive organizations, and the political development of the Socialist Party and its successor, Social Democrats, U.S.A., after 1958. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: English Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. -

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960S and 1970S by Kathryn B. C

“What Happened to the Post-War Dream?”: Nostalgia, Trauma, and Affect in British Rock of the 1960s and 1970s by Kathryn B. Cox A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology: History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor James M. Borders Professor Walter T. Everett Professor Jane Fair Fulcher Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Kathryn B. Cox [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6359-1835 © Kathryn B. Cox 2018 DEDICATION For Charles and Bené S. Cox, whose unwavering faith in me has always shone through, even in the hardest times. The world is a better place because you both are in it. And for Laura Ingram Ellis: as much as I wanted this dissertation to spring forth from my head fully formed, like Athena from Zeus’s forehead, it did not happen that way. It happened one sentence at a time, some more excruciatingly wrought than others, and you were there for every single sentence. So these sentences I have written especially for you, Laura, with my deepest and most profound gratitude. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Although it sometimes felt like a solitary process, I wrote this dissertation with the help and support of several different people, all of whom I deeply appreciate. First and foremost on this list is Prof. Charles Hiroshi Garrett, whom I learned so much from and whose patience and wisdom helped shape this project. I am very grateful to committee members Prof. James Borders, Prof. Walter Everett, Prof. -

Roosevelt Demands Slave Labor Bill in First Congress Message

The 18 And Their Jailers SEE PAGE 3 — the PUBLISHEDMILITANT IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE VOL. IX—No. 2 NEW YORK, N. Y„ SATURDAY, JANUARY 13, 1943' 267 PRICE: FIVE CENTS Labor Leaders Roosevelt Demands Slave Labor Will Speak A t Bill In First Congress Message Meeting For 12 © ' Congress Hoists Its Flag The C ivil Rights Defense Corhmittee this week announced First Act of New a list of distinguished labor and civil liberties leaders who will Calls For Immediate Action participate in the New York ‘‘Welcome Home” Mass Meeting for James P. Cannon, Albert Goldman, Farrell Dobbs and Felix Congress Revives Morrow, 4 of the 12 imprisoned Trotskyists who. are being re On Forced Labor Measures leased from federal prison on January 24. The meeting will be Dies Committee held at the Hotel Diplomat, 108 W. 43rd Street, on February Political Agents of Big Business Combine 2, 8 P. M. ®---------------------------------------------- By R. B e ll To Enslave Workers and Paralyze Unions Included among the speakers CRDC Fund Drive The members of the new Con who will greet the Minneapolis gress had hardly warmed their Labor Case prisoners are Osmond Goes Over Top By C. Thomas K. Fraenkel, Counsel for the seats when a coalition of Roose NEW YORK CITY, Jan. 8— American Civil Liberties Union; velt Democrats and Dewey Re-' Following on the heels of a national campaign A total of $5,500 was con James T. Farrell, noted novelist publicans led by poll-tax Ran tributed in the $5,000 Christ to whip up sentiment for labor conscription, Roose and CRDC National Chairman; kin of Mississippi, anti-semite, mas Fund Campaign to aid Benjamin S. -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964 -

Tune in the Beatles All These Years by Mark Lewisohn

Tune In The Beatles All These Years by Mark Lewisohn You're readind a preview Tune In The Beatles All These Years ebook. To get able to download Tune In The Beatles All These Years you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Unlimited ebooks*. Accessible on all your screens. *Please Note: We cannot guarantee that every file is in the library. But if You are still not sure with the service, you can choose FREE Trial service. Book Details: Review: Ive read a lot about the Beatles... Too much, Im sure... And this is BY FAR the best thing Ive ever read on this topic.The depth of the research is astonishing, the writing is impeccable... Its simply a perfect book of its kind. I *can not wait* for the other volumes.The only caveat to mention is that its definitely a book for people like me...... Original title: Tune In: The Beatles: All These Years 944 pages Publisher: Three Rivers Press; Reprint edition (October 11, 2016) Language: English ISBN-10: 1101903295 ISBN-13: 978-1101903292 Product Dimensions:6 x 1.6 x 9.2 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 15147 kB Book File Tags: mark lewisohn pdf, beatles fan pdf, brian epstein pdf, george martin pdf, john and paul pdf, wait for the next pdf, pete best pdf, must read pdf, well written pdf, early years pdf, looking forward pdf, paul and george pdf, beatles fans pdf, wait for volume pdf, thought i knew pdf, ever read pdf, early days pdf, rock and roll pdf, next volume pdf, recording sessions Description: Now in paperback, Tune In is the New York Times bestseller by the world’s leading Beatles authority – the first volume in a groundbreaking trilogy about the band that revolutionized music.The Beatles have been in our lives for half a century and surely always will be. -

Bl Oo M Sb U

B L O O M S B U P U B L I S H I N G R Y L O N D O N ADULT RIGHTS GUIDE 2 0 1 4 J305 CONTENTS FICTION . 3 NON-FICTION . 17 SCIENCE AND NatURE. 29 BIOGRAPHY AND MEMOIR ���������������������������������������������������������� 35 BUSINESS . 40 ILLUSTRATED AND NOVELTY NON-FICTION . 41 COOKERY . 44 SPORT . 54 SUBAGENTS. 60 Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. 50 Bedford Square Phoebe Griffin-Beale London WC1B 3DP Rights Manager Tel : +44 (0) 207 631 5600 Asia, US [email protected] Tel: +44 (0) 207 631 5876 www.bloomsbury.com [email protected] Joanna Everard Alice Grigg Rights Director Rights Manager Scandinavia France, Germany, Eastern Europe, Russia Tel: +44 (0) 207 631 5872 Tel: +44 (0) 207 631 5866 [email protected] [email protected] Katie Smith Thérèse Coen Senior Rights Manager Rights Executive South and Central America, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, Greece, Israel, Arabic speaking Belgium, Netherlands, Italy countries Tel: +44 (0) 207 631 5873 Tel: +44 (0) 207 631 5867 [email protected] [email protected] FICTION The Bricks That Built the Houses BLOOMSBURY UK PUBLICATION DATE: Kate Tempest 01/02/2016 Award-winning poet Kate Tempest’s astonishing debut novel elevates the ordinary to the EXTENT: 256 extraordinary in this multi-generational tale set in south London RIGHTS SOLD: Young Londoners Becky, Harry and Leon are escaping the city with a suitcase Brazil: Casa de Palavra; full of stolen money. Taking us back in time, and into the heart of the capital, The Bricks That Built the Houses explores a cross-section of contemporary urban life France: Rivages; with a powerful moral and literary microscope, exposing the everyday stories that lie The Netherlands: Het behind the tired faces on the morning commute, and what happens when your best Spectrum uniboek intentions don’t always lead to the right decisions. -

Impossible Author Dies at 70

ESSAY Henry Alford Impossible Author Dies at 70 [Impossible Author], who has died aged sounded like Bette Davis.10 ber of the National Rifle Association).14 He was 70, was a talented television journalist, writer But there were bad memories, too.11 It was barred from several hotels for trivial offenses and photographer; he was also a nightmare his habit, for example, to howl at the moon. In such as being found with his trousers round his drunk.1 He died of a heart attack in an airliner 1984 he was in a bar in California when other ankles in the corridor.15 “Mainly I sleep with over the Atlantic after an argument concern- drinkers took exception to his howling. Matters cats and the female,” he once said, describing ing what he insisted was his right to have his came to a head when he decided to exorcise a his domestic situation. “I love female.”16 The seat “upgraded.” 2 His body was discovered at- neighboring drinker, who hit him over the head most promising time for conversation was be- tired in a frogman’s outfit.3 with a shovel, shouting: “I’ll knock the Devil out tween 11:30 a.m. and 1 p.m. — after two double “I Am an Alcoholic” (1959) recounted how of you!”12 He also kept explosives, to blow the vodkas, but before the sixth.17 his political life had been ruined by the demon legs off pool tables or to pack in a barrel for [Impossible] was given his first shotgun drink.4 Meanwhile [Impossible] had developed target practice.13 He held several exhibitions at the age of 10.18 An empty bottle didn’t stand a curious technique for writing -

SERIES 3 September 2019 Issue 3

COMPLETELY BUCKINGHAM SERIES 3 September 2019 Issue 3 Star Buy ..................... 2 BC301FS £50 OFFER £40 09/01/07 Beatles. Signed Series 3 Checklist ..... 3 Allan Williams. Series 3 ...................... 5 Buying List ............... 18 Last Chance .......... 19 BC316 £20 OFFER £15 08/11/07 Lest We Forget doubled postmark. BC306B £45 23/04/07 Celebrating England - St George’s Day. Signed Geraldine McEwan, star of Miss Marple. BC321C £35 OFFER £25 13/03/08 Flown. Classic. BC326DS £29.95 17/07/08 Air Displays - Red Arrows & Concorde. Signed Test Pilot Peter Baker. BC331MS £35 OFFER £25 04/11/08 Christmas Pantomime. Signed Su Pollard. BC345S2 £75 08/10/09 Eminent Britons - Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Signed by David Burke & Edward Hardwicke, both played Dr. Watson. Call us on 01303 278137 www.buckinghamcovers.com Dear Collector, Each series seems to be become longer, with an outstanding choice of variations for most issues. During the summer holidays I took my youngest to London for a few days. We thoroughly enjoyed being tourists and taking in all the sights. My trip helped me decide on this Star Buy, see below for details. Happy Browsing & Best Wishes Vickie Star Buy BC324MS £30 OFFER £20 St Paul’s Cathedral. Signed by the Dean of St Paul’s. Did you know? St Paul’s Cathedral is one of the largest churches in the world and is located in the City of London on Ludgate Hill, the City’s highest point. It was designed by Sir Christopher Wren as an important part of a huge rebuilding plan after the Great Fire of London in 1666. -

The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1299 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Reiter, Roland: The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons. Bielefeld: transcript 2008. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1299. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839408858 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 3.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 3.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien.