The Army Lawyer: a History of the Judge Advocate General's Corps, 1775-1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

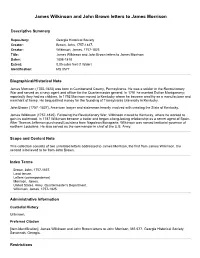

James Wilkinson and John Brown Letters to James Morrison

James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to James Morrison Descriptive Summary Repository: Georgia Historical Society Creator: Brown, John, 1757-1837. Creator: Wilkinson, James, 1757-1825. Title: James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to James Morrison Dates: 1808-1818 Extent: 0.05 cubic feet (1 folder) Identification: MS 0577 Biographical/Historical Note James Morrison (1755-1823) was born in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. He was a soldier in the Revolutionary War and served as a navy agent and officer for the Quartermaster general. In 1791 he married Esther Montgomery; reportedly they had no children. In 1792 Morrison moved to Kentucky where he became wealthy as a manufacturer and merchant of hemp. He bequeathed money for the founding of Transylvania University in Kentucky. John Brown (1757 -1837), American lawyer and statesman heavily involved with creating the State of Kentucky. James Wilkinson (1757-1825). Following the Revolutionary War, Wilkinson moved to Kentucky, where he worked to gain its statehood. In 1787 Wilkinson became a traitor and began a long-lasting relationship as a secret agent of Spain. After Thomas Jefferson purchased Louisiana from Napoleon Bonaparte, Wilkinson was named territorial governor of northern Louisiana. He also served as the commander in chief of the U.S. Army. Scope and Content Note This collection consists of two unrelated letters addressed to James Morrison, the first from James Wilkinson, the second is believed to be from John Brown. Index Terms Brown, John, 1757-1837. Land tenure. Letters (correspondence) Morrison, James. United States. Army. Quartermaster's Department. Wilkinson, James, 1757-1825. Administrative Information Custodial History Unknown. Preferred Citation [item identification], James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to John Morrison, MS 577, Georgia Historical Society, Savannah, Georgia. -

Advocate General Commissioned an Expert Group, Chaired by Sir David Edward, to Examine the Position 1

Scotland Act 2012 – commencement of provisions relating to Supreme Court appeals Following the coming into force of the Scotland Act 1998, the UK Supreme Court and its predecessors were given a role in determining “devolution issues” arising in court proceedings. Devolution issues under the 1998 Act include questions whether an Act of the Scottish Parliament is within its legislative competence, and whether the purported or proposed exercise of a function by a member of the Scottish Executive would be incompatible with any of the rights under the European Convention on Human Rights or with the law of the European Union. This included the exercise of functions by the Lord Advocate as prosecutor, with the effect that the Supreme Court was given a role defined in statute in relation to Scottish criminal cases for the first time. The Scotland Act 2012 makes substantial amendments to this aspect of the 1998 Act and creates a new scheme of appeals in relation to “compatibility issues”. “Compatibility issues” are questions arising in criminal proceedings about EU law and ECHR issues, or challenges to Acts of the Scottish Parliament on ECHR or EU law compatibility grounds. These issues would currently be dealt with as devolution issues under the regime created by the 1998 Act. Under the 2012 Act provisions, the remit of the UK Supreme Court is to determine the compatibility issue and then remit to the High Court for such further action as that court should see fit. The 2012 Act also imposes time limits in appeals to the Supreme Court in the new system and introduces the same time limit in appeals to the Supreme Court in relation to devolution issues arising in criminal proceedings. -

According to Advocate General Pitruzzella, a National Court Can

Court of Justice of the European Union PRESS RELEASE No 63/21 Luxembourg, 15 April 2021 Advocate General’s Opinion in Case C-882/19 Press and Information Sumal, S.L. v Mercedes Benz Trucks España S.L. According to Advocate General Pitruzzella, a national court can order a subsidiary company to pay compensation for the harm caused by the anticompetitive conduct of its parent company in a case where the Commission has imposed a fine solely on that parent company For that to be the case, the two companies must have operated on the market as a single undertaking and the subsidiary must have contributed to the achievement of the objective and the materialisation of the effects of that conduct By a decision issued in 2016, 1 the Commission imposed fines on a number of companies in the automotive sector, including Daimler AG, in respect of collusive arrangements on the pricing of trucks. Following that decision, the Spanish company Sumal S.L. asked the Spanish courts to order Mercedes Benz Trucks España S.L. (‘MBTE’), a subsidiary company of Daimler, to pay it the sum of approximately EUR 22 000 in compensation. According to Sumal, that amount corresponded to the increased price paid by it to MBTE when purchasing certain trucks manufactured by the Daimler Group as compared with the lower market price that it would have paid in the absence of those collusive arrangements. In that context, the Audiencia Provincial de Barcelona (Provincial Court, Barcelona, Spain), before which the case is being appealed, asks the Court of Justice, in essence, whether a subsidiary (MBTE) can be held liable for an infringement of the EU competition rules by its parent company (Daimler) and under what conditions such liability can arise. -

PDF Download Yeah Baby!

YEAH BABY! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jillian Michaels | 304 pages | 28 Nov 2016 | Rodale Press Inc. | 9781623368036 | English | Emmaus, United States Yeah Baby! PDF Book Writers: Donald P. He was great through out this season. Delivers the right impression from the moment the guest arrives. One of these was Austin's speech to Dr. All Episodes Back to School Picks. The trilogy has gentle humor, slapstick, and so many inside jokes it's hard to keep track. Don't want to miss out? You should always supervise your child in the highchair and do not leave them unattended. Like all our highchair accessories, it was designed with functionality and aesthetics in mind. Bamboo Adjustable Highchair Footrest Our adjustable highchair footrests provide an option for people who love the inexpensive and minimal IKEA highchair but also want to give their babies the foot support they need. FDA-grade silicone placemat fits perfectly inside the tray and makes clean-up a breeze. Edit page. Scott Gemmill. Visit our What to Watch page. Evil delivers about his father, the entire speech is downright funny. Perfect for estheticians and therapists - as the accent piping, flattering for all design and adjustable back belt deliver a five star look that will make the staff feel and However, footrests inherently make it easier for your child to push themselves up out of their seat. Looking for something to watch? Plot Keywords. Yeah Baby! Writer Subscribe to Wethrift's email alerts for Yeah Baby Goods and we will send you an email notification every time we discover a new discount code. -

1 “Pioneer Days in Florida: Diaries and Letters from the Settling of The

“Pioneer Days in Florida: Diaries and Letters from the Settling of the Sunshine State, 1800-1900” A Listing of Materials Selected for the Proposed Digital Project Provenance of Materials All materials come from the Florida Miscellaneous Manuscripts Collection in the P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History, Special Collections, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida. Diaries and family collections are stored by the name of the major creator/writer. Other items have individual call numbers and are stored in folders in a shelving area dedicated to all types of small collections and miscellaneous papers (19th and 20th century records and personal papers, print materials, photocopies of research materials from other archives, etc.). “Pioneer Days in Florida” will digitize only the original 19th century manuscripts in the possession of the University of Florida. Exclusions from scanning will include—blank pages in diaries; routine receipts in family papers; and non-original or photocopied materials sometimes filed with original manuscripts. About the Metadata The project diaries have corresponding UF Library Catalog Records. Family collections have EAD Finding Aids along with UF Library Catalog Records. Other items are described in an online guide called the Florida Miscellaneous Manuscripts Database (http://web.uflib.ufl.edu/miscman/asp/advanced.htm ) and in some cases have a UF Library Catalog Record (noted below when present). Diaries and Memoirs: Existing UF Library Catalog Records Writer / Years Covered Caroline Eliza Williams, 1811-1812, 1814, 1823 http://uf.catalog.fcla.edu/uf.jsp?st=UF005622894&ix=pm&I=0&V=D&pm=1 Vicente Sebastián Pintado, (Concessiones de Tierras, 1817) http://uf.catalog.fcla.edu/uf.jsp?st=UF002784661&ix=pm&I=0&V=D&pm=1 Mary Port Macklin, (Memoir, 1823/28) http://uf.catalog.fcla.edu/uf.jsp?st=UF002821999&ix=pm&I=0&V=D&pm=1 William S. -

Ambition Graphic Organizer

Ambition Graphic Organizer Directions: Make a list of three examples in stories or movies of characters who were ambitious to serve the larger good and three who pursued their own self-interested ambition. Then complete the rest of the chart. Self-Sacrificing or Self-Serving Evidence Character Movie/Book/Story Ambition? (What did they do?) 1. Self-Sacrificing 2. Self-Sacrificing 3. Self-Sacrificing 1. Self-Serving 2. Self-Serving 3. Self-Serving HEROES & VILLAINS: THE QUEST FOR CIVIC VIRTUE AMBITION Aaron Burr and Ambition any historical figures, and characters in son, the commander of the U.S. Army and a se- Mfiction, have demonstrated great ambition cret double-agent in the pay of the king of Spain. and risen to become important leaders as in politics, The two met privately in Burr’s boardinghouse and the military, and civil society. Some people such as pored over maps of the West. They planned to in- Roman statesman, Cicero, George Washington, and vade and conquer Spanish territories. Martin Luther King, Jr., were interested in using The duplicitous Burr also met secretly with British their position of authority to serve the republic, minister Anthony Merry to discuss a proposal to promote justice, and advance the common good separate the Louisiana Territory and western states with a strong moral vision. Others, such as Julius from the Union, and form an independent western Caesar, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Adolf Hitler were confederacy. Though he feared “the profligacy of often swept up in their ambitions to serve their own Mr. Burr’s character,” Merry was intrigued by the needs of seizing power and keeping it, personal proposal since the British sought the failure of the glory, and their own self-interest. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

The Insular Cases: the Establishment of a Regime of Political Apartheid

ARTICLES THE INSULAR CASES: THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A REGIME OF POLITICAL APARTHEID BY JUAN R. TORRUELLA* What's in a name?' TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ 284 2. SETFING THE STAGE FOR THE INSULAR CASES ........................... 287 2.1. The Historical Context ......................................................... 287 2.2. The A cademic Debate ........................................................... 291 2.3. A Change of Venue: The Political Scenario......................... 296 3. THE INSULAR CASES ARE DECIDED ............................................ 300 4. THE PROGENY OF THE INSULAR CASES ...................................... 312 4.1. The FurtherApplication of the IncorporationTheory .......... 312 4.2. The Extension of the IncorporationDoctrine: Balzac v. P orto R ico ............................................................................. 317 4.2.1. The Jones Act and the Grantingof U.S. Citizenship to Puerto Ricans ........................................... 317 4.2.2. Chief Justice Taft Enters the Scene ............................. 320 * Circuit Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. This article is based on remarks delivered at the University of Virginia School of Law Colloquium: American Colonialism: Citizenship, Membership, and the Insular Cases (Mar. 28, 2007) (recording available at http://www.law.virginia.edu/html/ news/2007.spr/insular.htm?type=feed). I would like to recognize the assistance of my law clerks, Kimberly Blizzard, Adam Brenneman, M6nica Folch, Tom Walsh, Kimberly Sdnchez, Anne Lee, Zaid Zaid, and James Bischoff, who provided research and editorial assistance. I would also like to recognize the editorial assistance and moral support of my wife, Judith Wirt, in this endeavor. 1 "What's in a name? That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet." WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, ROMEO AND JULIET act 2, sc. 1 (Richard Hosley ed., Yale Univ. -

French Armed Forces Update November 2020

French Armed Forces Update November 2020 This paper is NOT an official publication from the French Armed Forces. It provides an update on the French military operations and main activities. The French Defense Attaché Office has drafted it in accordance with open publications. The French Armed Forces are heavily deployed both at home and overseas. On the security front, the terrorist threat is still assessed as high in France and operation “Sentinelle” (Guardian) is still going on. Overseas, the combat units are extremely active against a determined enemy and the French soldiers are constantly adapting their courses of action and their layout plans to the threat. Impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic, the French Armed Forces have resumed their day-to-day activities and operations under the sign of transformation and modernization. DeuxIN huss arMEMORIAMds parachut istes tués par un engin explosif improvisé au Mali | Zone Militaire 09/09/2020 11:16 SHARE On September 5th, during a control operation within the Tessalit + region, three hussards were seriously injured after the explosion & of an Improvised Explosive Device. Despite the provision of + immediate care and their quick transportation to the hospital, the ! hussard parachutiste de 1ère classe Arnaud Volpe and + brigadier-chef S.T1 died from their injuries. ' + ( Après la perte du hussard de 1ere classe Tojohasina Razafintsalama, le On23 November 12th, during a routine mission in the vicinity of juillet, lors d’une attaque suicide commise avec un VBIED [véhicule piégé], le 1er Régiment de Hussards Parachutistes [RHP] a une nouvelle fois été Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, nine members of the Multinational endeuillé, ce 5 septembre. -

La Masacre De Ponce: Una Revelación Documental Inédita

LUIS MUÑOZ MARÍN, ARTHUR GARFIELD HAYS Y LA MASACRE DE PONCE: UNA REVELACIÓN DOCUMENTAL INÉDITA Por Carmelo Rosario Natal Viejos enfoques, nuevas preguntas Al destacar el cultivo de la historia de la memoria como uno de los tópicos en auge dentro la llamada “nueva historia cultural”, el distinguido académico de la Universidad de Cambridge, Peter Burke, hace el siguiente comentario en passant: “En cambio disponemos de mucho menos investigación…sobre el tema de la amnesia social o cultural, más escurridizo pero posiblemente no menos importante.”1 Encuentro en esta observación casual de Burke la expresión de una de mis preocupaciones como estudioso. Efectivamente, hace mucho tiempo he pensado en la necesidad de una reflexión sistemática sobre las amnesias, silencios y olvidos en la historia de Puerto Rico. La investigación podría contribuir al aporte de perspectivas ignoradas, consciente o inconscientemente, en nuestro acervo historiográfico. Lo que divulgo en este escrito es un ejemplo típico de esa trayectoria de amnesias y olvidos. La Masacre de Ponce ha sido objeto de una buena cantidad de artículos, ensayos, comentarios, breves secciones en capítulos de libros más generales y algunas memorias de coetáneos. Existe una tesis de maestría inédita (Sonia Carbonell, Blanton Winship y el Partido Nacionalista, UPR, 1984) y dos libros publicados recientemente: (Raúl Medina Vázquez, Verdadera historia de la Masacre de Ponce, ICPR, 2001 y Manuel E. Moraza Ortiz, La Masacre de Ponce, Publicaciones Puertorriqueñas, 2001). No hay duda de que los eventos de marzo de 1937 en Ponce se conocen hoy con mucho más detalles en la medida en que la historiografía y la memoria patriótica nacional los han mantenido como foco de la culminación a que conducía la dialéctica de la violencia entre el estado y el nacionalismo en la compleja década de 1930. -

Fy 2021 Competitive Grant Announcement Drug, Gang

ARIZONA CRIMINAL JUSTICE COMMISSION FY 2021 COMPETITIVE GRANT ANNOUNCEMENT DRUG, GANG, AND VIOLENT CRIME CONTROL PROGRAM Eligibility State, county, local, and tribal criminal justice agencies in Arizona that meet the qualifications are eligible to apply. Open Date: Applications may be started in GMS on Monday, February 10, 2020. Deadline All applications are due by 3:00 p.m. on Friday, March 6, 2020. For Assistance If you have any questions about this grant solicitation or are having difficulties with the Grant Management System, contact Simone Courter, Grant Coordinator, at 602-364-1186, Tony Vidale, Program Manager, at 602-364-1155 or e-mail [email protected]. Arizona Criminal Justice Commission 1110 W. Washington, Suite 230 Phoenix, AZ 85007 Office: (602) 364-1146 Fax: (602) 364-1175 ABOUT THE DRUG, GANG, AND VIOLENT CRIME CONTROL PROGRAM The Drug, Gang, and Violent Crime Control (DGVCC) program allow state, county, local, and tribal governments to support activities that combat drugs, gangs, and violent crime. The DGVCC program provides funding to support the components of a statewide, system-wide enhanced drug, gang, and violent crime control program as outlined in the Arizona 2020 Drug, Gang and Violent Crime Control State Strategy. The Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (Byrne JAG) funds awarded to Arizona by the United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance (DOJ/BJA) continue to support program activities along with state Drug, and Gang Enforcement Account (DEA) funds established under A.R.S. §41-2402. The Byrne JAG program provides states, tribes, and local governments with critical funding necessary to support a range of program areas including law enforcement, prosecution and courts, prevention and education, corrections and community corrections, drug treatment and enforcement, planning, evaluation, and technology improvement, and crime victim and witness initiatives. -

History and Art

Mediterranean, Knowledge, Culture and Heritage 6 Erminio FONZO – Hilary A. HAAKENSON Editors MEDITERRANEAN MOSAIC: HISTORY AND ART 0 - 8 0 - 99662 - 88 - 978 ISBN Online: ISBN Online: Mediterranean, Knowledge, Culture and Heritage 6 Mediterranean, Knowledge, Culture and Heritage Book Series edited by Giuseppe D’Angelo and Emiliana Mangone This Book Series, published in an electronic open access format, serves as a permanent platform for discussion and comparison, experimentation and dissemination, promoting the achievement of research goals related to three key topics: Mediterranean: The study of southern Europe and the Mediterranean world offers a historical perspective that can inform our understanding of the region today. The findings collected in this series speak to the myriad policy debates and challenges – from immigration to economic disparity – facing contemporary societies across the Great Sea. Knowledge: At its core, this series is committed to the social production of knowledge through the cooperation and collaboration between international scholars across geographical, cultural, and disciplinary boundaries. Culture and Heritage: This series respects and encourages sharing multiple perspectives on cultural heritage. It promotes investigating the full scope of the complexity, hybridity, and morphology of cultural heritage within the Mediterranean world. Each manuscript will be submitted to double-blind peer reviewing. Scientific Board Ines Amorin (UP – Portugal), Paolo Buchignani (UNISTRADA – Italy), Rosaria Caldarone (UNIPA