Abstract Masculinity on Every Channel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conservative Pipeline to the Supreme Court

The Conservative Pipeline to the Supreme Court April 17, 2017 By Jeffrey Toobin they once did. We have the tools now to do all the research. With the Federalist Society, Leonard Leo has reared a We know everything they’ve written. We know what they’ve generation of originalist élites. The selection of Neil Gorsuch is said. There are no surprises.” Gorsuch had committed no real just his latest achievement. gaffes, caused no blowups, and barely made any news— which was just how Leo had hoped the hearings would unfold. Leo has for many years been the executive vice-president of the Federalist Society, a nationwide organization of conservative lawyers, based in Washington. Leo served, in effect, as Trump’s subcontractor on the selection of Gorsuch, who was confirmed by a vote of 54–45, last week, after Republicans changed the Senate rules to forbid the use of filibusters. Leo’s role in the nomination capped a period of extraordinary influence for him and for the Federalist Society. During the Administration of George W. Bush, Leo also played a crucial part in the nominations of John Roberts and Samuel Alito. Now that Gorsuch has been confirmed, Leo is responsible, to a considerable extent, for a third of the Supreme Court. Leo, who is fifty-one, has neither held government office nor taught in a law school. He has written little and has given few speeches. He is not, technically speaking, even a lobbyist. Leo is, rather, a convener and a networker, and he has met and cultivated almost every important Republican lawyer in more than a generation. -

The Musical Number and the Sitcom

ECHO: a music-centered journal www.echo.ucla.edu Volume 5 Issue 1 (Spring 2003) It May Look Like a Living Room…: The Musical Number and the Sitcom By Robin Stilwell Georgetown University 1. They are images firmly established in the common television consciousness of most Americans: Lucy and Ethel stuffing chocolates in their mouths and clothing as they fall hopelessly behind at a confectionary conveyor belt, a sunburned Lucy trying to model a tweed suit, Lucy getting soused on Vitameatavegemin on live television—classic slapstick moments. But what was I Love Lucy about? It was about Lucy trying to “get in the show,” meaning her husband’s nightclub act in the first instance, and, in a pinch, anything else even remotely resembling show business. In The Dick Van Dyke Show, Rob Petrie is also in show business, and though his wife, Laura, shows no real desire to “get in the show,” Mary Tyler Moore is given ample opportunity to display her not-insignificant talent for singing and dancing—as are the other cast members—usually in the Petries’ living room. The idealized family home is transformed into, or rather revealed to be, a space of display and performance. 2. These shows, two of the most enduring situation comedies (“sitcoms”) in American television history, feature musical numbers in many episodes. The musical number in television situation comedy is a perhaps surprisingly prevalent phenomenon. In her introduction to genre studies, Jane Feuer uses the example of Indians in Westerns as the sort of surface element that might belong to a genre, even though not every example of the genre might exhibit that element: not every Western has Indians, but Indians are still paradigmatic of the genre (Feuer, “Genre Study” 139). -

Download Press Release As PDF File

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS - PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS ANNOUNCES PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN Emmy, Grammy and Academy Award Winning Hollywood Legend’s Trademark White Suit Costume, Iconic Arrow through the Head Piece, 1976 Gibson Flying V “Toot Uncommons” Electric Guitar, Props and Costumes from Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, Little Shop of Horrors and More to Dazzle the Auction Stage at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills All of Steve Martin’s Proceeds of the Auction to be Donated to BenefitThe Motion Picture Home in Honor of Roddy McDowall SATURDAY, JULY 18, 2020 Los Angeles, California – (June 23rd, 2020) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house to the stars, has announced PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN, an exclusive auction event celebrating the distinguished career of the legendary American actor, comedian, writer, playwright, producer, musician, and composer, taking place Saturday, July 18th, 2020 at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills and live online at juliensauctions.com. It was also announced today that all of Steve Martin’s proceeds he receives from the auction will be donated by him to benefit The Motion Picture Home in honor of Roddy McDowall, the late legendary stage, film and television actor and philanthropist for the Motion Picture & Television Fund’s Country House and Hospital. MPTF supports working and retired members of the entertainment community with a safety net of health and social -

2020Annual Report

2020 Annual Report DEAR FRIENDS With the Coronavirus national emergency declaration, Northern Illinois Hospice’s priorities shifted. Leadership pivoted and narrowed its scope to worldwide pandemic infection control and keeping patients and staff safe. By April 2020, the first individual with both a terminal diagnosis and COVID-19 was admitted. Now, more than 400 days have passed and COVID-19 has become an unwanted, extended guest of the American experience. Northern Illinois Hospice continues to be diligent with its emergency management efforts. Our team has done an amazing job, demonstrating the commitment, expertise, and quality and safety practices for which we are known. Beyond COVID-19, additionally last year: • A Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Loan was secured, which helped with payroll for several weeks during the peak of the pandemic, and Health and Human Services (HHS) stimulus funds were received to offset COVID-related expenses. • A Capital Improvement Fund was established to From left: Northern Illinois Hospice Chief Executive plan for future needs of our building. The Fund’s first Officer Lisa Novak and Board of Directors President Jon Aldrich priority was to replace the old, worn out roof. • The Board of Directors unanimously voted to expand into DeKalb County, increasing Northern Illinois Hospice’s service area from five counties to six. This mission expansion currently is underway. • Community outreach continued, and we partnered with organizations like the Alzheimer’s Association to present webinars tailored to individuals caring for seriously ill loved ones at home. We also teamed up with local nursing and assisted living facilities to offer events like Puppy Parades to bring joy to socially-isolated residents. -

BILL COSBY Biography

BILL COSBY Biography Bill Cosby is, by any standards, one of the most influential stars in America today. Whether it be through concert appearances or recordings, television or films, commercials or education, Bill Cosby has the ability to touch people’s lives. His humor often centers on the basic cornerstones of our existence, seeking to provide an insight into our roles as parents, children, family members, and men and women. Without resorting to gimmickry or lowbrow humor, Bill Cosby’s comedy has a point of reference and respect for the trappings and traditions of the great American humorists such as Mark Twain, Buster Keaton and Jonathan Winters. The 1984-92 run of The Cosby Show and his books Fatherhood and Time Flies established new benchmarks on how success is measured. His status at the top of the TVQ survey year after year continues to confirm his appeal as one of the most popular personalities in America. For his philanthropic efforts and positive influence as a performer and author, Cosby was honored with a 1998 Kennedy Center Honors Award. In 2002, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor, was the 2009 recipient of the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor and the Marian Anderson Award. The Cosby Show - The 25th Anniversary Commemorative Edition, released by First Look Studios and Carsey-Werner, available in stores or online at www.billcosby.com. The DVD box set of the NBC television hit series is the complete collection of one of the most popular programs in the history of television, garnering 29 Emmy® nominations with six wins, six Golden Globe® nominations with three wins and ten People’s Choice Awards. -

8 Pm 8:30 9 Pm 9:30 10 Pm 10:30 11 Pm A&E Live PD: Rewind (TV14) Live Live PD (TV14) Live PD -- Live PD (TV14) Live PD -- 10.17.19

Friday Prime-Time Cable TV 8 pm 8:30 9 pm 9:30 10 pm 10:30 11 pm A&E Live PD: Rewind (TV14) Live Live PD (TV14) Live PD -- Live PD (TV14) Live PD -- 10.17.19. Å PD: Rewind 317. (N) Å 04.10.20. (N) Å AMC The Karate Kid ›› (1986) Ralph Macchio, Noriyuki “Pat” The Karate Kid Part II ›› (1986) Ralph Mac- Morita. (PG) Å chio, Noriyuki “Pat” Morita. (PG) Å ANP Tanked: Sea-Lebrity Edition (TV14) Prankster-comedy duo Tanked (TVPG) Rock star DJ Tanked Jeff Dunham and Jeff Termaine order tanks with a sense Ashba wants another tank (TVPG) Shark of humor. (N) but he needs it ASAP. Å Byte. Å BBC From Russia Goldfinger ›››› (1964) Sean Connery, Gert Frobe. Agent 007 drives an Graham Norton With Love Aston Martin, runs into Oddjob and fights Goldfinger’s scheme to rob Fort Compilation. (1963) (6) Å Knox. (PG) Å (N) Å BET This Christmas ›› (2007) Delroy Lindo, Idris Welcome Home Roscoe Jenkins ›› (2008) Martin Lawrence, Elba. (PG-13) (7) Å James Earl Jones. (PG-13) Å Bravo Shahs of Sunset (TV14) GG Shahs of Sunset (TV14) Des- Watch What Shahs of Sunset (TV14) Des- undergoes emergency sur- tiney surprises Sara’s broth- Happens tiney surprises Sara’s broth- gery, and the crew rallies er, Sam, for his birthday. (TV14) (N) Å er, Sam, for his birthday. Å around her. Å (N) Å CMT Mom (TV14) Mom (TV14) Mom (TV14) Mom (TV14) Mom (TV14) Mom (TV14) Best Me (PG- Å Å Å Å Å Å 13) Å Com Tosh.0 (TV14) Tosh.0 (TV14) Tosh.0 (TV14) Tosh.0 (TV14) Kevin Hart: Seriously Funny Crank Yankers Ticket Girl. -

UNIVERSITY of Southern CALIFORNIA 11 Jan

UNIVERSAL CITY STUDIOS. INC. AN MCA INC. COMPANY r November 15, 1971 Dr. Bernard _R. Kantor, Chairman Division of Cinema University <;:>f S.outhern California University Park Los Angeles, Calif. 90007 Dear Dr. Kantor: Forgive my delay in answering your nice letter and I want to assure you I am very thrilled about being so honored by the Delta Kappa Al ha, and I most certainly will be present at the . anquet on February 6th. Cordia ~ l I ' Edi ~'h EH:mp 100 UNIVERSAL CITY PLAZA • UNIVERSAL CITY, CALIFORNIA 91608 • 985-4321 CONSOLIDATED FILM I DU TRIES 959 North Seward Street • Hollywood, California 90038 I (213) 462 3161 telu 06 74257 1 ubte eddr n CONSOLFILM SIDNEY P SOLOW February 15, 1972 President 1r. David Fertik President, DKA Uni ersity of Southern California Cinema Department Los Angels, California 90007 Dear Dave: This is to let you know how grateful I am to K for electing me to honorary membership. This is an honor, I must confess, that I ha e for many years dar d to hope that I would someday receive. So ;ou have made a dre m c me true. 'I he award and he widespread publici : th· t it achieved brought me many letters and phone calls of congra ulations . I have enjoyel teaching thee last twent, -four years in the Cinema Department. It is a boost to one's self-rep ct to be accepted b: youn , intelligent people --e peciall, those who are intere.ted in film-m·king . Please e t nJ my thanks to all t e ho ~ere responsible for selec ing me for honor ry~ m er_hip. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

1 Emily Jo Wharry HIST 490 Dec. 10, 2019 Student Club to Supreme Court: the Federalist Society's Origins on Law School Campuses

1 Emily Jo Wharry HIST 490 Dec. 10, 2019 Student Club to Supreme Court: The Federalist Society's Origins on Law School Campuses Following the election of President George W. Bush in January 2000, a 35-year-old Brett M. Kavanaugh joined the new White House legal team, taking a position as an associate counsel to the president.1 A couple of months into the job, Kavanaugh came across a news article about his past that frustrated him. The article described him as still being an active member of the Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies, a national organization of lawyers, judges, law school students, and professors who advocate for conservative legal doctrine and originalist interpretations of the United States Constitution. Worrying over this misreported detail, Kavanaugh wrote an email to his White House colleagues in which he assured them of the article's inaccuracy: "this may seem technical, but most of us resigned from the Federalist Society before starting work here and are not now members of the Federalist Society." Kavanaugh continued, "the reason I (and others) resigned from Fed society was precisely because I did not want anyone to be able to say that I had an ongoing relationship with any group that has a strong interest in the work of this office."2 Nineteen years later, in November 2019, the Federalist Society hosted its sold-out annual National Lawyers Convention at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, D.C. Kavanaugh, no 1 Scott Shane et al., “Influential Judge, Loyal Friend, Conservative Warrior — and D.C. Insider,” The New York Times, July 14, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/14/us/politics/judge-brett-kavanaugh.html. -

Dean Martin, La Voce Di “That’S Amore”

Dean Martin, la voce di “That’s amore” Dean Martin, pseudonimo di Dino Paul Crocetti (Martin deriva da Martino, cognome della madre molisana), nasce a Steubenville, nello stato dell'Ohio, il 7 giugno 1917. Abbandonata la scuola a sedici anni, compie diversi lavori, compreso il pugile e il benzinaio, fino a quando, con il nome d'arte di Dean Martin, s'impone come cantante a New York. E' il 25 luglio 1946 quando Dean Martin si esibisce per la prima volta in coppia con Jerry Lewis al "Club 500" di Atlantic City. I due artisti danno vita ad un duo comico di successo, che dura per un decennio esatto, realizzando anche quindici film di successo, da "La mia amica Irma" di George Marshall (1949) a "Hollywood o morte!" (1956), passando per "Irma va a Hollywood", "Il sergente di legno", "Quel fenomeno di mio figlio" e "Attente ai marinai", tutti di Hal Walker, tra il 1950 e il 1951, quindi "Il caporale Sam", "Il cantante matto", "Occhio alla palla", "Più vivo che morto", "Il nipote picchiatello" e "Mezzogiorno di fifa", tutti di Norman Taurog, tra il 1952 e il 1955. Ancora: "Morti di paura" e "I figli del secolo" di George Marshall (1953-54), "Il circo a tre piste" di Joseph Pevney (1954), "Artisti e modelle" e "Hollywood o morte!" di Frank Tashlin (1955-56). La coppia è legata anche a programmi televisivi, come il varietà di successo "The Colgate Comedy Hour" (1950), di cui diventano anche conduttori. Il sodalizio artistico s'interrompe il 24 luglio 1956. La carriera di Martin, nonostante la rottura della coppia, continua a mietere successi. -

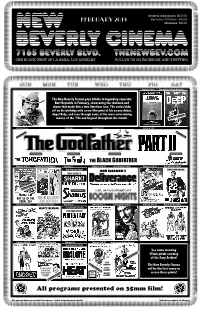

Newbev201902 FRONT

General Admission: $10.00 February 2019 Seniors / Children: $6.00 NEW Matinees: $6.00 BEVERLY cinema 7165 BEVERLY BLVD. THENEWBEV.COM ONE BLOCK WEST OF LA BREA, LOS ANGELES FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK AND TWITTER! February 1 & 2 Two written by Peter Benchley The New Beverly Cinema pays tribute to legendary superstar Burt Reynolds in February, showcasing the charisma and charm that made him a true American icon. The series kicks off on his birthday with a rare film print of his screen debut, Angel Baby, and runs through some of his most entertaining movies of the ‘70s and beyond throughout the month. 4-track Mag Print DIRECTED BY STEVEN SPIELBERG February 3 & 4 February 5 February 6 & 7 February 8 & 9 IB Tech Print IB Tech Print MIDNIGHT SHOW! MIDNIGHT SHOW! MIDNIGHT SHOW! MIDNIGHT SHOW! THE BLACK GODFATHER (SATURDAY ONLY) February 10 & 11 Directed by Paul Wendkos February 12 February 13 & 14Burt Reynolds Tribute February 15 & 16 Burt Reynolds Tribute Burt Reynolds Tribute JOHN BOORMAN’S BURT REYNOLDS Sam Fuller’s SHARK! Sony Archive Print SONY ARCHIVE PRINT PAUL THOMAS ANDERSON’S BATTLE OF THE GEORGE HAMILTON CORAL SEA BURT REYNOLDS February 17 & 18 French Foreign Legion February 19 February 20 & 21 Burt Reynolds Tribute February 22 & 23 Burt Reynolds Tribute MARTY FELDMAN Jamaa Fanaka Double LEON ISAAC KENNEDY February 24 & 25 Directed by Paul Wendkos February 26 February 27 & 28 Jack Lemmon Double Feature Burt Reynolds Tribute See some stunning 35mm prints courtesy of the Sony Archive! Sony Archive Print JACK Sony Archive Print LEMMON The -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003-