The Pope and the Second World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

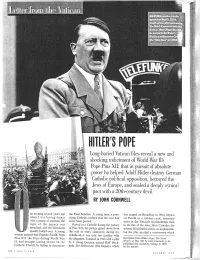

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Pius XII on Trial

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Pius XII on Trial Katherine M. Campbell University of Maine - Main, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Katherine M., "Pius XII on Trial" (2014). Honors College. 159. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/159 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PIUS XII ON TRIAL by Katherine M. Campbell A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology and Political Science) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: Henry Munson, Professor of Anthropology Alexander Grab, Professor of History Mark D. Brewer, Associate Professor of Political Science Richard J. Powell, Associate Professor of Political Science, Leadership Studies Sol Goldman, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science Copyright 2014 Katherine M. Campbell Abstract: Scholars have debated Pope Pius XII’s role in the Holocaust since the 1960s. Did he do everything he could and should have done to save Jews? His critics say no because of antisemitism rooted in the traditional Catholic views. His defenders say yes and deny that he was an antisemite. In my thesis, I shall assess the arguments on both sides in terms of the available evidence. I shall focus both on what Pius XII did do and what he did not do and on the degree to which he can be held responsible for the actions of low-level clergy. -

American Catholicism and the Political Origins of the Cold War/ Thomas M

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1991 American Catholicism and the political origins of the Cold War/ Thomas M. Moriarty University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Moriarty, Thomas M., "American Catholicism and the political origins of the Cold War/" (1991). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1812. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1812 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN CATHOLICISM AND THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR A Thesis Presented by THOMAS M. MORI ARTY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 1991 Department of History AMERICAN CATHOLICISM AND THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR A Thesis Presented by THOMAS M. MORIARTY Approved as to style and content by Loren Baritz, Chair Milton Cantor, Member Bruce Laurie, Member Robert Jones, Department Head Department of History TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. "SATAN AND LUCIFER 2. "HE HASN'T TALKED ABOUT ANYTHING BUT RELIGIOUS FREEDOM" 25 3. "MARX AMONG THE AZTECS" 37 4. A COMMUNIST IN WASHINGTON'S CHAIR 48 5. "...THE LOSS OF EVERY CATHOLIC VOTE..." 72 6. PAPA ANGEL I CUS 88 7. "NOW COMES THIS RUSSIAN DIVERSION" 102 8. "THE DEVIL IS A COMMUNIST" 112 9. -

The Catholic Church in the Czech Lands During the Nazi

STUDIA HUMANITATIS JOURNAL, 2021, 1 (1), pp. 192-208 ISSN: 2792-3967 DOI: https://doi.org/10.53701/shj.v1i1.22 Artículo / Article THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE CZECH LANDS DURING THE NAZI OCCUPATION IN 1939–1945 AND AFTER1 LA IGLESIA CATÓLICA EN LOS TERRITORIOS CHECOS DURANTE LA OCUPACIÓN NAZI ENTRE LOS AÑOS 1939–1945 Y DESPUÉS Marek Smid Charles University, Czech Republic ORCID: 0000-0001-8613-8673 [email protected] | Abstract | This study addresses the religious persecution in the Czech lands (Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia) during World War II, when these territories were part of the Bohemian and Moravian Protectorate being occupied by Nazi Germany. Its aim is to demonstrate how the Catholic Church, its hierarchy and its priests acted as relevant patriots who did not hesitate to stand up to the occupying forces and express their rejection of their procedures. Both the domestic Catholic camp and the ties abroad towards the Holy See and its representation will be analysed. There will also be presented the personalities of priests, who became the victims of the Nazi rampage in the Czech lands at the end of the study. The basic method consists of a descriptive analysis that takes into account the comparative approach of the spiritual life before and after the occupation. Furthermore, the analytical-synthetic method will be used, combined with the subsequent interpretation of the findings. An additional method, not always easy to apply, is hermeneutics, i.e., the interpretation of socio-historical phenomena in an effort to reveal the uniqueness of the analysed texts and sources and emphasize their singularity in the cultural and spiritual development of Czech Church history in the first half of the 20th century. -

Quellen Und Forschungen Aus Italienischen Archiven Und Bibliotheken

Quellen und Forschungen aus italienischen Archiven und Bibliotheken Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut in Rom Bd. 85 2005 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publi- kationsplattform der Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland (DGIA), zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht- kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich ver- folgt werden. QUELLEN UND FORSCHUNGEN AUS ITALIENISCHEN ARCHIVEN UND BIBLIOTHEKEN BAND 85 QUELLEN UND FORSCHUNGEN AUS ITALIENISCHEN ARCHIVEN UND BIBLIOTHEKEN HERAUSGEGEBEN VOM DEUTSCHEN HISTORISCHEN INSTITUT IN ROM BAND 85 MAX NIEMEYER VERLAG TÜBINGEN 2005 Redaktion: Alexander Koller Deutsches Historisches Institut in Rom Via Aurelia Antica 391 00165 Roma Italien http://www.dhi-roma.it ISBN 13: 9783-484-83085-1 ISBN 10: 3-484-83085-9 ISSN 0079-9068 ” Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 2005 Ein Unternehmen der K.G. Saur Verlag GmbH http://www.niemeyer.de Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages unzulässig und strafbar. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. Printed in Germany. Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier. Satz und Druck: AZ Druck und Datentechnik GmbH, Kempten/Allgäu Binden: Norbert Klotz, Jettingen-Scheppach INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Jahresbericht 2004 .................. IXÐLIII Hubert Mordek, Die Anfänge der fränkischen Ge- setzgebung für Italien ................ -

Pontifical Diplomacy, Hence of the Pope and with the Pope. State Diplomacy and Church Diplomacy by Monsignor Francesco Follo

Pontifical diplomacy, hence of the Pope and with the Pope. State Diplomacy and Church Diplomacy by Monsignor Francesco Follo Introduction The title and content of this contribution refers to various texts, the most recent of which are two conferences delivered respectively on November 15th, 2019 by H.E. Mgr. Paul Richard Gallagher Secretary for Relations with States, and on November 28th, 2019 by H.E. Card. Pietro Parolin, Secretary of State of His Holiness. Obviously, the prolusions of these high prelates helped me to formulate and - above all - to clarify my presentation of Vatican diplomacy, taking into account its history and its specificity. Actually, if all diplomacy works for peace, that of the Holy Father and his close contributors excludes a priori war as an extreme form of diplomacy and is always inspired by transcendent, religious values. In this regard, on November 15th 2019, in the conference entitled “Diplomacy of Values and Development”, H.E. Mons. Paul Richard Gallagher, Secretary for Relations with States, affirmed that the Holy See's diplomacy is «essentially aimed at pursuing the “values” that are proper to the Christian Revelation and that coincide with the deepest aspirations of Justice, Truth and Peace, which, although historically declined and with a variety of forms through the ecclesial Magisterium, are in their essence common to the man of every place, time and social extraction». The Eminent Archbishop then clarified that the relationship with values is at first sight something foreign to the common notion of diplomacy, as a science and art of the conduct of international relations. Diplomacy is at the service of the government of the State and pursues its ends: it is pure method that does not look at values. -

The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 Ii Introduction Introduction Iii

Introduction i The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 ii Introduction Introduction iii The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930 –1965 Michael Phayer INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bloomington and Indianapolis iv Introduction This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by John Michael Phayer All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and re- cording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of Ameri- can University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Perma- nence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Phayer, Michael, date. The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 / Michael Phayer. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-253-33725-9 (alk. paper) 1. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958—Relations with Jews. 2. Judaism —Relations—Catholic Church. 3. Catholic Church—Relations— Judaism. 4. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945) 5. World War, 1939– 1945—Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 6. Christianity and an- tisemitism—History—20th century. I. Title. BX1378 .P49 2000 282'.09'044—dc21 99-087415 ISBN 0-253-21471-8 (pbk.) 2 3 4 5 6 05 04 03 02 01 Introduction v C O N T E N T S Acknowledgments ix Introduction xi 1. -

DIRECTOR: Rafael Luis Breide Obeid CONSEJO CONSULTOR: Roberto Brie (†), Antonio Caponnetto, Mario Caponnetto, Alberto Caturell

BIBLIOTECA DEL PENSAMIENTO CATÓLICO AÑO 20 - Nº 56 PASCUA DE 2003 DIRECTOR: Rafael Luis Breide Obeid CONSEJO CONSULTOR: Roberto Brie (†), Antonio Caponnetto, Mario Caponnetto, Alberto Caturelli, Enrique Díaz Araujo, Jorge N. Ferro, P. Miguel A. Fuentes, Héctor H. Hernández, P. Pedro D. Martínez, Federico Mihura Seeber, Ennio Innocenti, Patricio H. Randle, Víctor E. Ordóñez, Carmelo Palumbo, Héctor Piccinali, Thomas Molnar, Diego Ibarra, P. Alfredo Sáenz FUNDACIÓN GLADIUS: M. Breide Obeid, H. Piccinali, J. Ferro, P. Rodríguez Barnes, E. Zancaner, E. Rodríguez Barnes, Z. Obeid La Fundación Gladius es miembro fundador de la Sociedad Internacional Tomás de Aquino (SITA), Sección Argentina La compra de las obras del fondo editorial y las suscripciones se pueden efectuar me- diante cheques y/o giros contra plaza Buenos Aires, a la orden de “Fundación Gladius” C. C. 376 (1000) Correo Central, Cap. Fed. Asimismo, puede escribir a la Fundación Gladius, para simple correspondencia o envío de artículos y/o recensiones: telefax 4803-4462 / 9426 ~ [email protected] Correspondencia a: FUNDACIÓN GLADIUS, C.C. 376 (1000) Correo Central, Bs. As., Rep. Argentina. Los artículos que llevan firmas no comprometen necesariamente el pensamiento de la Fundación y son de responsabilidad de quien firma. PARA LA VENTA Y DISTRIBUCIÓN DE EDICIONES GLADIUS Y SUSCRIPCIONES VÓRTICE EDITORIAL Y DISTRIBUIDORA Hipólito Yrigoyen 1970 (C1089AAL) Buenos Aires Telefax: 4952-8383 ~ [email protected] FRANQUEO PAGADO Impreso por EDICIONES BARAGA Concesión Nº 4039 del Centro Misional Baraga Colón 2544, Remedios de Escalada Buenos Aires, República Argentina Correo TARIFA REDUCIDA Central B Central Argentino Concesión Nº 1077 Agosto de 2002 Queda hecho el depósito que establece la ley 11.723 ISBN Nº 950-9674-56-7 Índice RAFAEL L. -

A History of Catholic Antisemitism: the Dark Side of the Church

pal-michael-00fm 11/29/07 4:09 PM Page i A History of Catholic Antisemitism This page intentionally left blank pal-michael-00fm 11/29/07 4:09 PM Page iii A History of Catholic Antisemitism The Dark Side of the Church Robert Michael pal-michael-00fm 11/29/07 4:09 PM Page iv a history of catholic antisemitism Copyright © Robert Michael, 2008. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2008 by PALGRAVE MACMILLANTM 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS. Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN-13: 978-0-230-60388-2 ISBN-10: 0-230-60388-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Michael, Robert, 1936– A history of Catholic antisemitism : the dark side of the church / Robert Michael. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-230-60388-2 1. Judaism—Relations—Catholic Church. 2. Catholic Church—Relations— Judaism. 3. Christianity and antisemitism—History. 4. Antisemitism—History. 5. Catholic Church—History. 6. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945) I. Title. BM535.M5 2007 261.2’609—dc22 2007035490 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. -

Inter Arma Caritas

COLLECTANEA ARCHIVI VATICANI 52 INTER ARMA CARITAS L’U FFICIO INFORMAZIONI VATICANO PER I PRIGIONIERI DI GUERRA ISTITUITO DA PIO XII (1939-1947) II Documenti CITTÀ DEL VATICANO ARCHIVIO SEGRETO VATICANO 2004 COLLECTANEA ARCHIVI VATICANI, 52 ISBN 88-85042-39-2 TUTTI I DIRITTI RISERVATI © Copyright 2004 by Archivio Segreto Vaticano DOCUMENTI a cura di FRANCESCA Di GIOVANNI e GIUSEPPINA ROSELLI AVVERTENZA Al fine di proporre un saggio della ricca, molteplice e varia tipologia delle carte conservate nel fondo Ufficio Informazioni Vaticano (Prigio- nieri di guerra, 1939-1947) si presenta una serie di documenti scelti ope- rando un semplice sondaggio; il criterio, apparentemente empirico, è tuttavia dovuto alla effettiva vastità, dal punto di vista qualitativo e quan- titativo, delle pratiche archiviate. Le lettere pubblicate sono state raccolte in ventuno capitoli pensati seguendo un ideale corso dello svolgimento del conflitto fin dai momen- ti iniziali del settembre 1939. Tale suddivisione è parsa opportuna allo scopo di evitare un confuso mescolamento che non avrebbe reso giusti- zia all’intensità degli scritti e al valore storico che da essi scaturisce. All’interno di ogni capitolo le lettere, che si susseguono secondo un ordine cronologico, sono state trascritte fedelmente, nel totale rispetto degli usi linguistici, stilistici, grafici e grammaticali, anche se talvolta pa- lesemente errati, non consueti o peregrini (ad esempio raddoppiamenti delle consonanti, utilizzo dell’apostrofo, delle maiuscole, degli accenti); l’unico intervento attuato, laddove strettamente necessario, è segnalato da indicazioni poste tra parentesi quadre. Per lo stesso motivo si sono la- sciate abbreviazioni e sigle di uso frequente, quali ad esempio AOI (Afri- ca orientale italiana), btg. -

![Thomas Brechenmacher (Hrsg.): Das Reichskonkordat 1933. Forschungsstand, Kontroversen, Dokumente, Paderborn [U. A.] 2007](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0354/thomas-brechenmacher-hrsg-das-reichskonkordat-1933-forschungsstand-kontroversen-dokumente-paderborn-u-a-2007-4430354.webp)

Thomas Brechenmacher (Hrsg.): Das Reichskonkordat 1933. Forschungsstand, Kontroversen, Dokumente, Paderborn [U. A.] 2007

Thomas Brechenmacher (Hrsg.): Das Reichskonkordat 1933. Forschungsstand, Kontroversen, Dokumente, Paderborn [u. a.] 2007. (= Veröffentlichungen der Kommission für Zeitgeschichte, Reihe B: Forschungen, Bd. 109) The present volume originated in a Giornate di Studi organized by the publisher at the German Historical Institute in Rome on 17 June 2004. Under the title »The End of Political Catholicism in Germany in 1933 and the Holy See: Enabling Law, Reich Concordat and Dissolution of the Center Party,« the participants were called upon to debate the »state of research, scholarly perspectives, and new sources 25 years after the Scholder-Repgen controversy.« 1 The immediate catalyst for reexamining these questions of the Center Party’s demise and the beginnings of the Reich Concordat, questions that had long been quiescent, was the opening of files pertaining to Germany from the papacy of Pius XI (1922–1939) by the Vatican Secret Archive in February 2003. An important collection of sources from one of the main historical actors, The Holy See – to which only selected individuals had previously been given access – was now open to the wider scholarly community. That alone would have been reason enough to ask both established and younger scholars of recent church history whether they expected the newly opened Vatican files to shed new light on the »question of the Reich Concordat« or had perhaps already gained new understanding as a result of their work with these sources. The fact that around the same time other important archives and collections were made accessible, or were being prepared for opening, provided further impetus for a scholarly »stock-taking.« In late 2002, the archive of the Archdiocese of Munich and Freising made available the papers of Archbishop Michael Cardinal Faulhaber. -

Acta Apostolicae Sedis

ACTA APOSTOLICAE SEDIS COMMENTARIUM OFFICIALE ANNUS XVII - VOLUMEN XVII ROMAE TYPIS POLYGLOTTIS VATICANIS M DCCCCXXV r 4 •i Annus XVII - Voi. XVÍI 15 Ianuarii 19215 Numi. 1 ACTA APOSTOLICAE SEDIS COMMENTARI UM OFFICIALE CONSTITUTIO APOSTOLICA CAE TH AGINEN SIS IN" INDIIS ERECTIO PRAEFECTURAE APOSTOLICAE DE «SINU» PIUS EPISCOPUS SERVUS SERVORUM DEI AD PERPETUAM REI MEMORIAM Christi Domini mandatum i «Ite, docete omnes gentes», prae oculte habentes, a quo, meritis licet imparibus, ad Petri cathedram, inopinato I>ei consilio, evecti fuimus, nihil inexpertum omisimus, quod ad Evangelium in orbem propagandum tentari posset. Quoad igitur difficiles temporis nostri condiciones id permittebant, summa ope contendimus, ut novae Missiones constituerentur, prout rerum locorumque opportunitas requi- rebat. Quum autem in finibus Carthaginensis dioecesis in Columbiana Repu blica, regio adsit Sinu nuncupata, ubi plura millia infidelium originis vulgo Indianae nuncupatae incolunt, ad eos aliosque ibi commorantes melius pleniusque evangelizandos et in fide christianisque moribus insti tuendos, expedire visum est ut Missio aliqua seu Praefectura Apostolica ibi constitueretur. Quum vero venerabilis frater Archiepiscopus Carthaginensis in hanc sen tentiam prorsus conveniret, et dilectus filius Noster Ioannes Cardinalis Benlloch j Vivó, Archiepiscopus Burgensis, onus in se susciperet depu tandi ad hoc Missionis opus sacerdotes Seminarii sui pro Missionibus exteris Burgis fundati, suffragante quoque Nuntio Apostolico penes Columbia- 6 Acta Apostolicae Sedis