Research Master Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Perceived Causes and Control of Students' Crises in Higher

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol 3, No 10, 2012 Perceived Causes and Control of Students’ Crises in Higher Institutions in Lagos State, Nigeria . Prof. Olu AKEUSOLA 1 *Olumuyiwa VIATONU 2 Dr ASIKHIA, O. A. 3 1. Provost, Michael Otedola College of Primary Education, Noforija, P. M. B. 1028 Epe, Lagos State, Nigeria. e-mail: [email protected] Tel: (234) (0) 8060777771 2. School of Education, Michael Otedola College of Primary Education, Noforija P. M. B. 1028 Epe, Lagos State, Nigeria e-mail : [email protected] Tel: (234) (0) 8023051674 3. Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Michael Otedola College of Primary Education, Noforija, P. M. B. 1028, Epe, Lagos State, Nigeria. E-mail : [email protected] Tel: (234) (0) 7039538804 * Corresponding author Abstract The study investigated perceived causes and control of students’ crises in higher institutions in Lagos State, Nigeria. The population comprised all students, staff, students’ union executive members and heads of the six sampled higher institutions. Four structured questionnaires were used to collect data from 954 samples used for the study. A test-retest method with a correlation coefficient (r) of 0.84 was used to determine the reliability of the instruments. Data collected were analyzed using percentages, frequency counts, correlations analysis and t-test through the SPSS package. The findings revealed the following: state- owned higher institutions were more prone to students’ crises than federal institutions; increase in tuition fees and inadequate attention to students’ welfare were major causes of student crises whiles stable and moderate tuition fees was perceived as a good control measure to curb students’ crises. -

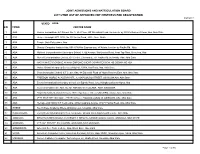

Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board 2017 Utme List of Approved Cbt Centress for Registration 3/21/2017

JOINT ADMISSIONS AND MATRICULATION BOARD 2017 UTME LIST OF APPROVED CBT CENTRESS FOR REGISTRATION 3/21/2017 STATE- ABIA S/N TOWN CENTRE NAME 1 ABA Golden Foundations Int'l School, No. 1, GFI Close, Off Ovurukwu Road, Umuobeke by 352 Portharcourt Road, Aba, Abia State 2 ABA Unique Unibright INT'L SCH, No 152 faulks Road , ABA , Abia- North 3 ABA Temple Gate Polytechnic, Aba 4 ABA Okwyzil Computer Institute Aba, KM 4 PH/Aba Express way, off Ariaria Junction by Faulks Rd. Abia 5 ABA National Comprehensive Secondary School, 1, Oji Avenue, Via Omoba Road, Near 7up Plant, Umoukea, Aba 6 ABA Mchief Communication Limited, ICT Centre, 2 ikenna st., off Faulks Rd, by Nwala, Aba, Abia State 7 ABA MATAR MISERICORDIAE HUMAN EMPOWERMENT COMPUTER SCH, 4B OBOHIA RD ABA 8 ABA Makac Global Intergrated Services Nig Ltd., 63/64, Asa Road, Aba, Abia State 9 ABA Giant Immaculate School ICT Centre Aba, 48 Dikenafai Road off Ngwa Road by East, Aba, Abia State 10 ABA FREEDOM WORLD ACADEMY INT'L, 12 OKPOMUBO STREET, OSISIOMA Aba, Abia State 11 ABA Ekcela International Secondary School, 23, Egbelu Road, Umuehilegbu Osisioma-Ngwa, Aba 12 ABA Covenant Polythecnic, Aba, No 321 ABA-Owerri Road,ABA , ABIA ,OSISIOMA 13 ABA Bright Stars International Schools, 10/12, Ikpemaeze Street, UMUIKPO, Ariaria, Aba, Abia State 14 ABA JP FLINCT INT'L SCHOOL, 279/281 Umueze Road/Udeagbala rd, OSISIOMA, Aba, Abia State 15 ABA Heritage and Infinity ICT Centre Aba, 4 Ezenwagbara Avenue off 279 Faulks Road, Aba, Abia State 16 EHERE Sound Base Academy, Ehere,Obingwa LGA, Umuahia, Abia State 17 ISIALA-NGWA Living Bread International School, Umuoleke, Omoba Isiala-Ngwa South L.G.A., Abia State 18 OBINGWA BENJYN INTERNATIONA ACADEMEY, 1 BENJYN AVENUE AMORJI UKWU, OBINGWA.ABIA STATE 19 OBINGWA JET AGE PRIVATE SCH,AMAPU, OBINGWA,ABIA OBINGWA 20 OWERRINTA Adventist Sec. -

AD/Afenifere: the Squandering of Heritage

ADAfenifere The Squandering of Heritage Page 1 of 6 AD/Afenifere: The Squandering of Heritage By Dr. Wale Adebanjo Now that the Yoruba have overwhelmingly voted, as the election results indicate, for the People's Democratic Party, we must note that it will not be the first time a people will vote against what they do not 'like' and vote for what they do not 'need'. The electoral defeat of AD has come to be seen as a major rupture in Yoruba politics. It is not. Rather, it is the consolidation of a process that began much earlier but distinctively in 1998/1999 when the Afenifere leadership started behaving like autocratic inheritors of a democratic legacy. In an earlier essay, 'Obasanjo, Yoruba and the Future of Nigeria' (ThisDay, The Sunday Newspaper, February 16, 2003), I had referred to the soon-to-be ex-Governor Bisi Akande's statement that the soon-to-be two-term President Olusegun Obasanjo would always be an embarrassment to himself. I had added, crucially, that that was not the whole truth, and that it was an abdication of the predisposition to face the whole political truth, for, indeed, President Olusegun Obasanjo would always be an embarrassment to the Yoruba. Now, Akande, who made bold to reveal this partial truth, has been kicked out of Osun State Government House and Obasanjo, about whom the partial truth was revealed, has been overwhelmingly returned to Aso Rock Villa. Beyond that, Akande's party, the Alliance for Democracy, has been overwhelmingly rejected by the people for whom it was primarily created, and Obasanjo's party, the People's Democratic Party, a largely derelict association of mostly light-hearted buccaneers, has been overwhelmingly voted into the government houses in the West, except Lagos. -

Michael Otedola College of Primary Education, Order

MICHAEL OTEDOLA COLLEGE OF PRIMARY EDUCATION, NOFORIJA, KM. 7, EPE-IJEBU-ODE ROAD P.MB. 1028, EPE, LAGOS STATE E-mail: [email protected] ORDER OF PROCEEDINGS AT THE 3RD CONVOCATION /20TH ANNIVERSARY CEREMONIES FOR 2000-2008 PART TIME, 2011/2012, & 2012/2013 For the Award of Nigeria Certificate in Education (NCE), Presentation of Prizes and Conferment of Fellowship Date: Saturday, December 6, 2014. Time: 10:00a.m Venue: Convocation Ground, MOCPED, Noforija-Epe, Lagos State. 1 MICHAEL OTEDOLA COLLEGE OF PRIMARY EDUCATION, NOFORIJA, KM. 7, EPE-IJEBU-ODE ROAD P.MB. 1028, EPE, LAGOS STATE E-mail: [email protected] ORDER OF PROCEEDINGS AT THE 3RD CONVOCATION /20TH ANNIVERSARY CEREMONIES FOR 2000-2008 PART TIME, 2011/2012, & 2012/2013 For the Award of Nigeria Certificate in Education (NCE), Presentation of Prizes and Conferment of Fellowship Date: Saturday, December 6, 2014. Time: 10:00a.m Venue: Convocation Ground, MOCPED, Noforija-Epe, Lagos State. 2 MODERATOR AND PRINCIPAL OFFICERS OF THE COLLEGE HIS EXCELLENCY MR. BABATUNDE RAJI FASHOLA (SAN) Executive Governor of Lagos State and Moderator of the College MRS. RISIKAT T. AKESODE Chairman, Governing Council PROF. OLU AKEUSOLA, NCE, B.A (Hons), M.A; Ph.D, MNIM, MITD Provost DR. S.A. POPOOLA B.A, PGDE, M.A, Ph.D Deputy Provost BOLA Y. SHITTU CPA, B.SC, MPA Registrar and Secretary to Council MR. GABRIEL O. ONIFADE NCE, B.SC, M.SC College Librarian MR. GANIYU A. AJOSE B.SC, M.SC, ACA. College Bursar 3 PICTURE HIS EXCELLENCY, MR. BABATUNDE RAJI FASHOLA (SAN) Executive Governor of Lagos State and Moderator of the College 4 PICTURE HER EXCELLENCY, MRS. -

Asiwaju Bolanle Ahmed Adekunle Tinubu

This is the biography of Asiwaju Bolanle Ahmed Adekunle Tinubu. ASIWAJU: THE BIOGRAPHY OF BOLANLE AHMED ADEKUNLE TINUBU by Moshood Ademola Fayemiwo, PhD and Margie Neal-Fayemiwo, Ed.D Order the complete book from the publisher Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/9183.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. ASIWAJU THE BIOGRAPHY OF BOLANLE AHMED ADEKUNLE TINUBU Moshood Ademola Fayemiwo and Margie Neal-Fayemiwo Copyright © 2017 by Moshood Ademola Fayemiwo & Margie Neal- Fayemiwo Paperback ISBN: 978-1-63492-251-7 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, photocopying, recording or otherwise without written permission from the authors, except for brief excerpts in newspaper reviews. The editing format of this book used The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage revised and expanded edition by Alan Siegal and William Connolly 1999 with thanks. A Publication of The Jesus Christ Solution Center, DBA, USA in collaboration with Booklocker Publishing Company Inc. St Petersburg, Florida USA Printed on acid-free paper. Cover Design Concept: Muhammad Bashir, Abuja Nigeria Cover Design by: Todd Engel Photos: - Olanre Francis, Washington DC Photos and Inner Page Layout: Brenda van Niekerk, South Africa First Edition: 2017 The Jesus Christ Newspaper Publishing Company Nigeria Limited (RC: 1310616) Tel: 0812-198- 5505; Email: [email protected] The Jesus Christ Solution Center, DBA USA (FEIN: 81-5078881) and its subsidiaries are registered trademarks licensed to conduct legitimate business activities in the United States of America. -

Jamb-Cbt-Centres

JOINT ADMISSIONS AND MATRICULATION BOARD ABIA 2018 CBT REGISTRATION CENTRES S/N REFERENCE NO CENTRE 1 UTME2017/01070008 Abia State e- Library, Ogurube Layout, Before House Of Assembly, Umuahia, Abia State 2 UTME2017/01010018 Abia State Polytechnic, Aba Owerri Road, Aba, Abia State 3 UTME2017/01070001 Amable Nig. Limited, 7, Old Timber Road, Umuahia, Abia State 4 UTME2018/01000005 BE DE EXCEL PLANET COMPUTERS, #4 EXCEL CLOSE OFF AHIAFOR JUNCTION, OPOBO RD, UKWA EAST LGA ABIA STATE 5 UTME2017/01010001 Bright Stars International Schools, 10/12, Ikpeamaeze Street, Umuikpo, Ariaria, Aba, Abia State 6 UTME2017/01070002 Clems Business Systems Ltd., Plot 111B, Eghem Layout, Corporate Affairs Building, BCA Road, Umuahia, Abia State 7 UTME2017/01010002 Covenant Polythecnic, Aba, No 321 ABA-Owerri Road, Aba, Abia State 8 UTME2018/01000001 DIAMOND HIGH SCHOOLS, 2-6 DIAMOND AVENUE OFF OHANKU, UGWUNAGBO LGA, ABIA STATE 9 UTME2017/01070003 Doreen Institute of Computer Technologies, Opp. National Population Commission, New Haven Junction, Along Holy Ghost Road By Aba Road, Umuahia, Abia State. 10 UTME2018/01000002 ENE'S COMP.SEC.SCH. ICT, OWERRINTA ABIA STATE 11 UTME2017/01010004 Freedom World Academy Int'l, 12 Okpu-Umobo Street, Osisioma, Aba, Abia State. 12 UTME2017/01100001 Gates Gifted and Talented Educational Services Ltd. Otodo High School, Asaga, Ohafia, Abia State. 13 UTME2017/01090002 Gregory University, Amaokwe Achara, Uturu, Abia State 14 UTME2017/01010007 Heritage and Infinity ICT Centre Aba, 4 Ezenwagbara Avenue off 279 Faulks Road, Aba, -

Institution Name Abia State University, Uturu. Abubakar

INSTITUTION NAME ABIA STATE UNIVERSITY, UTURU. ABUBAKAR TAFAWA BALEWA UNIVERSITY, BAUCHI ADEKUNLE AJASIN UNIVERSITY, AKUNGBA-AKOKO ADELEKE UNIVERSITY, EDE, OSUN STATE ADENIRAN OGUNSANYA COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, OTTO/IJANIKIN ADEYEMI COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, (AFFLIATED TO OBAFEMI AWOLOWO UNIVERSITY, ILE-IFE, OSUN STATE) AFE BABALOLA UNIVERSITY , ADO-EKITI AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA AIR FORCE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY NIGERIAN AIR FORCE, KADUNA AJAYI CROWTHER UNIVERSITY, OYO AKANU IBIAM FEDERAL POLYTECHNIC, UNWANA, AFIKPO AKWA IBOM STATE UNIVERSITY, IKOT-AKPADEN AKWA-IBOM STATE POLYTECHNIC, IKOT-OSURUA AL- HIKMAH UNIVERSITY, ILORIN AL-QALAM UNIVERSITY, KATSINA ALVAN IKOKU COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, (AFFLIATED TO UNIVERSITY OF NIGERA, NSUKKA) AMBROSE ALLI UNIVERSITY, EKPOMA AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA , YOLA AUCHI POLYTECHNIC, AUCHI BABCOCK UNIVERSITY, ILISHAN-REMO, BAUCHI STATE UNIVERSITY, GADAU, BAUCHI STATE BAYERO UNIVERSITY, KANO BAZE UNIVERSITY, FCT, ABUJA BELLS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, OTA BENSON IDAHOSA UNIVERSITY, BENIN CITY BENUE STATE UNIVERSITY, MAKURDI BINGHAM UNIVERSITY, KARU BOWEN UNIVERSITY, IWO CALEB UNIVERSITY, IMOTA CARITAS UNIVERSITY, AMORJI-NIKE, ENUGU CHUKWUEMEKA ODUMEGWU OJUKWU UNIVERSITY, ULI COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND ANIMAL SCIENCE, MANDO ROAD, KADUNA COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, AKWANGA COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, AZARE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, GIDAN-WAYA, KAFANCHAN COVENANT UNIVERSITY, CANAAN LAND, OTA CRAWFORD UNIVERSITY OF APOSTOLIC FAITH MISSION FAITH CITY, IGBESA CROSS RIVERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, CALABAR DELTA STATE POLYTECHNIC, OGWASHI-UKU, DELTA STATE POLYTECHNIC, OZORO DELTA STATE UNIVERSITY, ABRAKA EBONYI STATE UNIVERSITY, ABAKALIKI EKITI STATE UNIVERSITY, ADO-EKITI ELIZADE UNIVERSITY, ILARA-MOKIN, ONDO STATE ENUGU STATE UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, ENUGU FCT COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, ZUBA, FED COLLEGE OF EDUC. (TECH.) UMUNZE, AFFILIATED TO (NNAMDI AZIKIWE UNIVERSITY, AWKA) FED. COLLEGE OF EDUC. -

152 Effective Teaching Practice Supervison: a Predictor of Teacher Trainees' Performance in Pedagogy

An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 5 (4), Serial No. 21, July, 2011 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) Effective Teaching Practice Supervison: A Predictor of Teacher Trainees’ Performance in Pedagogy (Pp. 152-160) Lawal, Bashir O. - Department of Teacher Education, University of Ibadan Viatonu, Olumuyiwa - School of Education, Michael Otedola College of Primary Education, Noforija- Epe, Lagos State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] & Jegede, A. Adebowale - School of Education and Dean, Students’ Affairs Michael Otedola College of Primary Education, Noforija- Epe, Lagos State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The quality of teachers prepared for basic education in Africa and other continents of the world is a consequence of the knowledge of content acquired and the pedagogy. Effective teaching practice supervision could determine the level of teacher trainees’ performance in the art of teaching. The study investigated the differences in performance of teacher trainees who embarked on continuous Teaching Practice and Supervision – TP & S (of twelve weeks) and those of non-continuous teaching practice and supervision – TP & S (of six weeks in two installments). It equally examined whether there was a relationship or not in the performance of teacher trainees when they are team supervised and when they are not teamed supervised in Copyright ©IAARR 2011: www.afrrevjo.com 152 Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info Vol. 5 (4), Serial No. 21, July, 2011. Pp. 152-160 pedagogy. Five hundred (500) teacher trainees were randomly selected as samples from two (2) colleges of education owned by Lagos State Government of Nigeria. They are Adeniran Ogunsanya College of Education (AOCOED), Ijanikin and Michael Otedola College of Primary Education (MOCPED), Noforija-Epe. -

Corruption in Higher Education in Nigeria: Prevalence, Structures and Patterns Among Students of Higher Education Institutions in Nigeria

Corruption in Higher Education in Nigeria: Prevalence, Structures and Patterns among students of higher education institutions in Nigeria By Sakiemi A. Idoniboye-Obu 208518002 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in Political Science, School of Social Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg Campus, South Africa Supervisors Professor Nwabufo Okeke Uzodike Dr Alison Jones 2014 i Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own unaided original work. All citations, references, borrowed ideas, and sources have been properly acknowledged. It is being submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Humanities, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg. No part of the present work has been submitted previously for any examination or degree in any other University. -------------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------- Sakiemi Abbey Idoniboye-Obu Professor Nwabufo Okeke-Uzodike ------------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------- Date Date ii Dedication To The Holy One of Israel Who makes all things beautiful in His own time; the Sovereign Lord, Wisdom and Power of God, Captain of the Lord’s host, the Beginning and the End, the Author and Finisher of my faith, Owner and Keeper of my soul, my Lord, my All, Jesus Christ. Thank You, Lord. And To Her whom He used to complete me HP My Wife, My Sister, My Friend and Lover Tamunotonye Ibimina Idoniboye-Obu iii Acknowledgement Saying “thank you” is one of the most difficult things to do, simple as the phrase sounds. This is more so when very many people made varying degrees of contribution to the project for which the thank you is to be said. Who to mention first, what adjective to describe the person’s (or institution’s) contribution to the final product, and whose names to omit are just some of the problems. -

Jambulletin 14-06-2021.Cdr

JUNE 14, 2021 Vol.2 No. 28 Chairman: COMPLETION OF 2021 UTME/DE REGISTRATION FOR Dr. Fabian Benjamin Members: CANDIDATES WHO DID NOT REGISTER WITHIN THE Abdulrahman Akpata Mohammed Ashumate Ismaila Jimoh STIPULATED TIME AND THE EXTENSION PERIOD Ijeoma Onyekwere Graphics Editor: Nikyu Bakau Correspondents: Ronke Fadayomi Obinna Pius Evelyn Akoja Computer Typesetting: Dorcas Omolara Akinleye Cameraman: Prince Kalu Circulation: Gabriel Ajodo Martha Abo Bridget Magnus Candidates queuing up for registration at a Professional Registration Centre while observing social distancing t the end of the period originally candidates who, largely due to issues related Pg 2 LIST OF DELISTED CENTRES FOR VARIOUS INFRACTIONS/ scheduled for the 2021/2022 to newly introduced pre-requisite of OFFENCES AUTME/DE registration on the 15th National Identification Number(NIN), could Pg 2 2021 UTME: PRINT NOTIFICATION SLIP FROM JUNE, 14 2021 May 2021, the registration period was not register. An additional extension of two weeks was extended by another two weeks up to the FINANCIAL REPORT OF INFLOW AND OUTFLOW FOR THE 29th of May, 2021 to accommodate made to compile the list of all prospective Pg 5 TH TH PERIOD OF 5 JUNE 2021 TO 11 JUNE 2021 Contd in Pg 2 SPECIAL NOTES TO ALL JAMB “FIGHT MALPRACTICE THE EXAMINATION OFFICIALS AND LAGOS WAY” - OLOYEDE CANDIDATES rof. Is-haq Oloyede, Registrar, Joint Admissions and Matriculations 1. Biometric Verification will be the only mode Board (JAMB), has commended the Lagos State Government for for the admittance of candidates into the Pdemonstrating exemplary leadership in the fight against examination centre. Strict adherence to the examination malfeasance by sanctioning 27 schools indicted for guide on compulsory biometric verification examination irregularities. -

Approved Cbt Centress for Registration 3/25/2017

JOINT ADMISSIONS AND MATRICULATION BOARD 2017 UTME LIST OF APPROVED CBT CENTRESS FOR REGISTRATION 3/25/2017 STATE- ABIA S/N TOWN CENTRE NAME 1 ABA Bright Stars International Schools, 10/12, Ikpemaeze Street, UMUIKPO, Ariaria, Aba, Abia State 2 ABA CITIZEN INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL 3 ABA Covenant Polythecnic, Aba, No 321 ABA-Owerri Road,ABA , ABIA ,OSISIOMA 4 ABA Ekcela International Secondary School, 23, Egbelu Road, Umuehilegbu Osisioma-Ngwa, Aba 5 ABA FREEDOM WORLD ACADEMY INT'L, 12 OKPOMUBO STREET, OSISIOMA Aba, Abia State 6 ABA Giant Immaculate School ICT Centre Aba, 48 Dikenafai Road off Ngwa Road by East, Aba, Abia State 7 ABA Golden Foundations Int'l School, No. 1, GFI Close, Off Ovurukwu Road, Umuobeke by 352 Portharcourt Road, Aba, Abia State 8 ABA Heritage and Infinity ICT Centre Aba, 4 Ezenwagbara Avenue off 279 Faulks Road, Aba, Abia State 9 ABA JP FLINCT INT'L SCHOOL, 279/281 Umueze Road/Udeagbala rd, OSISIOMA, Aba, Abia State 10 ABA Makac Global Intergrated Services Nig Ltd., 63/64, Asa Road, Aba, Abia State 11 ABA MATAR MISERICORDIAE HUMAN EMPOWERMENT COMPUTER SCH, 4B OBOHIA RD ABA 12 ABA Mchief Communication Limited, ICT Centre, 2 ikenna st., off Faulks Rd, by Nwala, Aba, Abia State 13 ABA National Comprehensive Secondary School, 1, Oji Avenue, Via Omoba Road, Near 7up Plant, Umoukea, Aba 14 ABA Okwyzil Computer Institute Aba, KM 4 PH/Aba Express way, off Ariaria Junction by Faulks Rd. Abia 15 ABA Temple Gate Polytechnic, Aba 16 ABA Unique Unibright INT'L SCH, No 152 faulks Road , ABA , Abia- North 17 EHERE Sound Base Academy, Ehere,Obingwa LGA, Umuahia, Abia State 18 ISIALA-NGWA Living Bread International School, Umuoleke, Omoba Isiala-Ngwa South L.G.A., Abia State 19 OBINGWA BENJYN INTERNATIONA ACADEMEY, 1 BENJYN AVENUE AMORJI UKWU, OBINGWA.ABIA STATE 20 OBINGWA JET AGE PRIVATE SCH,AMAPU, OBINGWA,ABIA OBINGWA 21 OHAFIA GIFTED AND TALENTED EDUC.