Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Nothing but the Truth': Genre, Gender and Knowledge in the US

‘Nothing but the Truth’: Genre, Gender and Knowledge in the US Television Crime Drama 2005-2010 Hannah Ellison Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film, Television and Media Studies Submitted January 2014 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. 2 | Page Hannah Ellison Abstract Over the five year period 2005-2010 the crime drama became one of the most produced genres on American prime-time television and also one of the most routinely ignored academically. This particular cyclical genre influx was notable for the resurgence and reformulating of the amateur sleuth; this time remerging as the gifted police consultant, a figure capable of insights that the police could not manage. I term these new shows ‘consultant procedurals’. Consequently, the genre moved away from dealing with the ills of society and instead focused on the mystery of crime. Refocusing the genre gave rise to new issues. Questions are raised about how knowledge is gained and who has the right to it. With the individual consultant spearheading criminal investigation, without official standing, the genre is re-inflected with issues around legitimacy and power. The genre also reengages with age-old questions about the role gender plays in the performance of investigation. With the aim of answering these questions one of the jobs of this thesis is to find a way of analysing genre that accounts for both its larger cyclical, shifting nature and its simultaneously rigid construction of particular conventions. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16 A70 TV Acad Ad.Qxp Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16_A70_TV_Acad_Ad.qxp_Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1 PROUD MEMBER OF »CBS THE TELEVISION ACADEMY 2 ©2016 CBS Broadcasting Inc. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER AS THE QUANTITY AND QUALITY OF CONTENT HAVE INCREASED in what is widely regarded as television’s second Golden Age, so have employment opportunities for the talented men and women who create that programming. And as our industry, and the content we produce, have become more relevant, so has the relevance of the Television Academy increased as an essential resource for television professionals. In 2015, this was reflected in the steady rise in our membership — surpassing 20,000 for the first time in our history — as well as the expanding slate of Academy-sponsored activities and the heightened attention paid to such high-profile events as the Television Academy Honors and, of course, the Creative Arts Awards and the Emmy Awards. Navigating an industry in the midst of such profound change is both exciting and, at times, a bit daunting. Reimagined models of production and distribution — along with technological innovations and the emergence of new over-the-top platforms — have led to a seemingly endless surge of creativity, and an array of viewing options. As the leading membership organization for television professionals and home to the industry’s most prestigious award, the Academy is committed to remaining at the vanguard of all aspects of television. Toward that end, we are always evaluating our own practices in order to stay ahead of industry changes, and we are proud to guide the conversation for television’s future generations. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Big Ed's City Market Restaurant

DOWNTOWN DINING ARTIST PROFILE SIGN UP TO WIN! Good eats downtown Adam Peele’s art & Win free tickets, with old (Big Ed’s) & Raleigh Devil plans for gift certificates new (La Volta) world domination READER and more REWARDS RALEIGHDOWNTOWNERMAGAZINE—Vol. 6, ISSUE 7 features 3. Downtown Eats 20. Local History: Behind the Books— Integration in the Wake County Public School System Post Office Box 27603 | Raleigh, NC 27611-7603 www.RaleighDowntowner.com | www.raleigh2.com 21. Getting ‘Round the Roundabout on Two Wheels Please call to schedule an office appointment 25. A Weeklong Dining Extravaganza 27. Triangle Modernist Houses Announces 2010 Modernist Home Tour 919.821.9000 Advertising inquiries: arts & entertainment [email protected] 10. Arts Together: 26 Years & Counting General press releases: 12. @ Art: Art News [email protected] 13. Artist Profile: Adam Peele 23. Local Music: Love Language B-to-B press releases and biz section info: [email protected] food & wine General office inquiries: 8. Let’s Do Lunch: Big Ed’s City Market Restaurant [email protected] 14. Bartender to Bartender ———— 15. Uncorked: Bring on the Beaujolais Publisher / Owner Crash Gregg 18. Downtown Dining: La Volta Founders Sig Hutchinson, Randall Gregg Food Editor Brian Adornetto Copy Editor Melissa Santos business Music Editor Dan Strobel 18. Neighborhood News Business Sales Director David Bartos 24. Plans Begin for the Capital Boulevard Corridor Senior Writer Peter Eichenberger 28. Downtown Snapshot From the Downtown Raleigh Alliance Lead Designer Katie Severa 29. 10 Questions with Mitchell Silver—Director of Planning for the City of Raleigh Assistant Designer Savannah Beckler, Marina 30. -

TRIANGLE TRIBUNE.COM the Triangle Black Wall Street

WWW.TRIANGLE TRIBUNE.COM The Triangle Black Wall Street makes a Bycomeback Rob Gourley The Durham VOICE DURHAM – More than 300 minority entrepreneurs gathered for three days of networking, promoting and music at Black Wall Street Homecoming in RIBUNE Durham. TTHE TRIANGLE’S CHOICE FOR THE BLACK VOICE The event, which was co-founded by local entrepreneurs Dee McDougal, Jesica Averhart, Talib Graves-Manns and Tobias Rose, was a chance for African-American and other minority entrepreneurs to engage with other VOLUME 18 NO. 36 WEEK OF OCTOBER 30, 2016 $1.00 successful entrepreneurs. Graves-Manns, whose family has lived in the Walltown Village neighbor- hood of Durham for four generations, said they created the event to honor the history of Black Wall Street in Durham, as well as to change media rep- Shaw gets its first resentations of black entrepreneurship. football win of the “The narrative is not really balanced when it comes to the press about African-Americans doing amazing things, especially in business,” he said. season. The Bears The first BWS homecoming was held last year. After its success, addi- tional events were held in Washington, D.C., and Austin, Texas. host homecoming “Most people here they think about either of those two cities (Durham this Saturday. and Tulsa, Oklahoma), but it’s technically more like 46 or 48 other Black Wall Street communities. They just didn’t have the same monikers. So, Washington, D.C., is one of them,” Graves-Manns said. This year’s event was also a success, and Graves-Mann said it is the guests who attend that are key. -

Televi and G 2013 Sion, Ne Graphic T 3 Writer Ews, Rad

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 6, 2012 2013 WRITERS GUILD AWARDDS TELEVISION, NEWS, RADIO, PROMOTIONAL WRITING, AND GRAPHIC ANIMATION NOMINEES ANNOUNCED Los Angeles and New York – The Writers Guild of Ameerica, West (WGAW) and the Writers Guild of America, East (WGAE) have announced nominaations for outstanding achievement in television, news, radio, promotional writing, and graphic animation during the 2012 season. The winners will be honored at the 2013 Writers Guild Awards on Sunday, February 17, 2013, at simultaneous ceremonies in Los Angeles and New York. TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Boardwalk Empire, Written by Dave Flebotte, Diane Frolov, Chris Haddock, Rolin Jones, Howard Korder, Steve Kornacki, Andrew Schneider, David Stenn, Terence Winter; HBO Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gouldd, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Becckett; AMC Game of Thrones, Written by David Benioff, Bryan Cogman, George R. R. Martin, Vanessa Taylor, D.B. Weiss; HBO Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm; Showtime Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Brett Johnson, Janeet Leahy, Victor Levin, Erin Levy, Frank Pierson, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner; AMC -more- 2013 Writers Guild Awards – TV-News-Radio-Promo Nominees Announced – Page 2 of 7 COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Kay Cannon, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Vali -

Legeros Fire Blog Archives 2006-2015

Philly versus Raleigh - Legeros Fire Blog Archives 2006-2015 Legeros Fire Blog Archives 2006-2015 - Philly versus Raleigh » Xmas Lights at Statio… Philly versus Raleigh 12/27/05 22 W - + 15 - 33 Idle curiosity regarding Raleigh's incoming fire chief compels me to compile this: http://www.legeros.com/temp/chart.htm Here’s his picture, on the far right: http://www.phila.gov/fire/newsletter/p14.. Legeros - 12/30/05 - 14:38 Name: (real name Remember personal info? preferred) Yes E-mail: (optional) No Web Site: (optional) Comment: / Textile Comment moderation is enabled on this site. This means that your comment will not be visible on this site until it has been approved by an editor. To prevent spam we require you to answer this silly question What are the FIRST TWO LETTERS of the word 'fire'? (Register your username / Log in) Notify: Yes, send me email when someone replies. Hide email: Yes, hide my email address. Small print: All html tags except <b> and <i> will be removed from your comment. You can make links by just typing the url or mail-address. https://www.legeros.com/ralwake/photos/weblog/pivot/entry.php?id=0006[10/13/2019 6:38:10 PM] Xmas Lights at Station 11 - Legeros Fire Blog Archives 2006-2015 Legeros Fire Blog Archives 2006-2015 - Xmas Lights at « Philly versus Raleigh… » CHFD has updated thei… Station 11 Xmas Lights at Station 11 12/27/05 19 W, 1 I - + 18 - 31 Here's a nice picture of Station 11 that appeared on firenews.net.. -

Ÿþm I C R O S O F T W O R

NORTH CAROLINA STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE Office of Archives and History Department of Cultural Resources NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Rochester Heights Historic District Raleigh, Wake County, WA4581, Listed 12/7/2011 Nomination by Sybil Argintar Photographs by Sybil Argintar, August 2010 Calloway Drive Doby Circle 513 Bailey Drive Historic District Map NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. _________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. Name of property________________________________________________________________________________ historic name __Rochester Heights Historic District________________________________________________ -

South Park Blocks Master Plan

0 South Park Blocks Master Plan Draft Preferred Design Community Comment Report November 2020 South Park Blocks Draft Preferred Design Community Comment Report 1 Contents Introduction Page 2 Survey Respondent Demographics Page 3 Major Themes from Focus Groups Page 5 Survey Results Page 6 Focus Group Summaries Page 40 Comments Submitted by Email Page 42 South Park Blocks Master Plan Project www.portlandoregon.gov/parks/spb Contact: Barbara Hart 503-823-5596 [email protected] South Park Blocks Draft Preferred Design Community Comment Report 2 Introduction Portland Parks & Recreation is working with the community to develop a plan for a South Park Blocks that is safe, accessible and welcoming for all Portlanders. The plan will address key challenges and opportunities, including maintaining a healthy tree canopy, making the park more accessible for all users, retaining park character while enhancing connections, and providing space for community events. Portland Parks & Recreation began the South Parks Block planning process by convening a community advisory committee to guide the project and launching a community visioning process in Summer 2019 to inform the development of three draft design concepts. The draft concepts were shared with the community in Fall 2019. The feedback on the design concepts guided the development of a draft preferred design. The community engagement approach for this stage of the project was designed to: • Enlist community participation in the design review process with a special focus on PSU students, the Native American Community Advisory Council and Parks Accessibility Advisory Committee; • Explain how community feedback and ideas heard during the draft concept phase influenced the development of Draft Preferred Design; • Gather and understand community feedback on the Draft Preferred Design to develop a preferred park design; and, • Strengthen community relationships and build support for the South Park Blocks and PP&R. -

Steve Pritzker Papers, 1967-1986

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4489q3bs No online items Finding Aid for the Steve Pritzker papers, 1967-1986 Processed by Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Steve Pritzker PASC 44 1 papers, 1967-1986 Title: Steve Pritzker papers Collection number: PASC 44 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 16 linear ft.(38 boxes) Date: 1967-1986 Abstract: Steve Pritzker was a writer and producer whose credits include the television series Room 222, Friends and Lovers, and Silver Spoons. Collection consists of television scripts and production material related to Pritzker's career. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Provenance/Source of Acquisition Gift, 1989. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Steve Pritzker Papers (Collection PASC 44). Library Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles. -

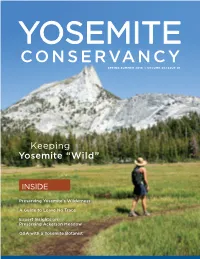

Yosemite Conservancy Spring.Summer 2016 :: Volume 07.Issue 01

YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY SPRING.SUMMER 2016 :: VOLUME 07.ISSUE 01 Keeping Yosemite “Wild” INSIDE Preserving Yosemite’s Wilderness A Guide to Leave No Trace Expert Insights on Preserving Ackerson Meadow Q&A with a Yosemite Botanist PHOTO: (RIGHT) © KARL KROEBER. PHOTO: MISSION Providing for Yosemite’s future is our passion. We inspire people to support projects and programs that preserve and protect Yosemite National Park’s resources and enrich the visitor experience. PRESIDENT’S NOTE YOSEMITE CONSERVANCY COUNCIL MEMBERS Yosemite’s Wilderness CHAIR PRESIDENT & CEO Philip L. Pillsbury Jr.* Frank Dean* he word wilderness might sound VICE CHAIR VICE PRESIDENT, forbidding, or it might conjure up a Bob Bennitt* CFO & COO Jerry Edelbrock sense of adventure. In an increasingly crowded world, national parks — and their protected Wilderness areas — provide COUNCIL important space, solace, and a refuge for both Hollis & Matt Adams* Jean Lane Jeanne & Michael Adams Walt Lemmermann* wildlife and humans. Some years ago, I had Gretchen Augustyn Melody & Bob Lind the privilege to ski with good friends into a Susan & Bill Baribault Sam & Cindy Livermore snowed-under Tuolumne Meadows. We had Meg & Bob Beck Anahita & Jim Lovelace Suzy & Bob Bennitt* Mark Marion & the meadows to ourselves and enjoyed a full David Bowman & Sheila Grether-Marion moon that reflected off the snow to make it Gloria Miller Patsy & Tim Marshall almost as bright as daylight. It was an amazing experience. Tori & Bob Brant* Kirsten & Dan Miks Marilyn & Allan Brown Robyn & Joe Miller More than 95 percent of visitors to Yosemite spend their time in Yosemite Steve & Diane Ciesinski* Janet Napolitano Sandy & Bob Comstock Dick Otter Valley, Mariposa Grove, or along Tioga Road. -

Congressional Record—House H4474

H4474 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE July 10, 2002 that legislation before this Chamber I understood this principle long ago. jump off first and with all the treas- next week. I understood how forfeitures and cer- ures. I would like to discuss my and many tificates became literally overnight This is not a simple problem about a others’ beliefs that a great inequity ex- methods to circumvent payment lim- few bad apples. The problems are sys- ists in our farm policy that has been its. I introduced the reform of farm temic, and the accounting practices of passed in the farm bill, and the fact subsidy payments during the House de- America must be changed so we will be that we have a chance to correct that bate on the farm bill last October; how- able to restore our economic health. inequity in this appropriations bill. ever, our farm policy, driven by our ag- We must support legislation like that This is not a new topic in Congress ricultural committee leadership favors in Senator SARBANES’ bill, legislation and, as well, it is not a new topic on the certificates that can be used as the that will provide real corporate respon- the floor of the House. As a farmer and loophole or end run to those very large sibility. His bill calls for a strong, inde- a former administrator of farm pro- farms. pendent board to oversee the auditing grams at USDA, as a member of the The Senate, however, successfully of public companies, assures the inde- Committee on Agriculture, I, like most implemented reasonable payment lim- pendence of auditors, and provides for of us, know the importance of pro- its and curtailed the unlimited use of reform that will protect investors.