Linking the Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greenham and Crookham Plataeu

Greenham and Crookham Plataeu Encompasses the whole plateau from Brimpton to Greenham and the slopes along the Kennet Valley in the north and the River Enborne in the south and east. Includes some riverside land along the Enborne in the south, where the River forms the boundary. Extends west to include a group of woodlands at Sandleford. Joint Character Area: Thames Basin Heaths Geology: The plateau has a large area of Silchester Gravel the overlies London Clay Sand (Bagshot Beds) which is found in a band at the edge of the Gravel. There are also some areas of Head at the edge of the top of the plateau. The slopes are London Clay Formation clay, silt and sand. There is alluvium along the Enborne Valley. The western section has a similar geology with Silchester Gravel, London Clay Sand ad London Clay Formation. Topography: a flat plateau that slopes away to river valleys in the north, south and east. The western area is the south facing slope at the edge of the plateau as it extends westwards into the developed land at Wash Common. Biodiversity: · Heathland and acid grassland: Extensive heathland and acid grassland areas at Greenham Common with small areas at Bowdown Woods and remnants at the mainly wooded Crookham Common and at Greenham Golf Course. · Lowland Mixed Deciduous Woodland: Extensive areas on the plateau slopes. Bowdown Woods and the areas within Greenham Common SSSI. · Wet Woodland: found in the gullies on the slopes at the plateau edge. · Other habitat and species: farmland near Brimpton supports good populations of farmland birds. -

Greenham Common Bulletin

Greenham Berkshire Buckinghamshire Common Bulletin Oxfordshire Managing your common for you 2nd Edition, winter 2015/16 Take the Wild Ride for Wildlife Crookham Commons. Wild Ride for Wildlife challenge! Cycle from Greenham The Wild Ride for Wildlife is being 8 to 11 September 2016 Common to Paris and raise funds organised by experienced event 200 miles for local nature reserves managers, Global Adventure Challenges. 3 days cycling Sign up to the 200-mile Wild Ride for Seasoned long-distance cyclists and Accommodation provided Wildlife from Greenham Common to enthusiasts who would like to take on Minimum sponsorship £1,300 Paris, and help to protect the amazing the challenge can find out more at a birds, flowers, reptiles and insects of West Wild Ride Information Evening on the 27 Berkshire. January at the Nature Discovery Centre in Thatcham. The Wild Ride for Wildlife will take place in September 2016, but cyclists are For more information visit: encouraged to sign up now to start bbowt.org.uk/wildride fundraising and training for the ride Contact the Fundraising Team on through southern England and northern [email protected] France. or 01865 775476. Funds raised on the Wild Ride for Wildlife will help us to look after heathland E W RID nature reserves such as Greenham and ILD Wallington Adrian for Wildlife Grazing on Greenham Common attle have been present on the ownership. A total of 50 active badger commons since 2001 and are setts have so far been recorded and to owned and grazed using historical date we have vaccinated 29 badgers C 2 commoners’ rights. -

Rides Flier 2018

Free social bike rides in the Newbury area Date Ride DescriptionRide Distance Start / Finish Time NewburyNewbury - Crockham - Wash Common Heath - - West Woolton Woodhay Hill - - West Mills beside 0503 Mar 1911 miles 09:30 Inkpen - Marsh BallBenham Hill - -Newbury Woodspeen - Newbury Lloyds Bank Newbury - BagnorKintbury - Chieveley- Hungerford - World's Newtown End - West Mills beside 1917 Mar 2027 miles 09:30 HermitageEast Garston - Cold Ash- Newbury - Newbury Lloyds Bank NewburyNewbury - Greenham - Woodspeen - Headley - Boxford -Kingsclere - - West Mills beside 072 Apr Apr 2210 miles 09:30 BurghclereWinterbourne - Crockham - HeathNewbury - Newbury Lloyds Bank NewburyNewbury - Crockham - Watership Heath Down - Kintbury - Whitchurch - Hungerford - - West Mills beside 1621 Apr 2433 miles 09:30 HurstbourneWickham Tarrant - Woodspeen - Woodhay - Newbury - Newbury Lloyds Bank NewburyNewbury - Cold - Enborne Ash - Hermitage - Marsh Benham - Yattendon - - West Mills beside 0507 May 2511 miles 09:30 HermitageStockcross - World's End - Bagnor - Winterbourne - Newbury - Newbury Lloyds Bank NewburyNewbury - Greenham - Highclere - Ecchinswell - Stoke - Ham - Inhurst - - West Mills beside 1921 May 3430 miles 09:30 Chapel Row -Inkpen Frilsham - Newbury - Cold Ash - Newbury Lloyds Bank NewburyNewbury - Crockham - Wash Heath Common - Faccombe - Woolton - Hurstbourne Hill - West Mills beside 024 Jun Jun 1531 miles 09:30 Tarrant East- Crux & EastonWest Woodhay - East Woodhay - Newbury - Newbury Lloyds Bank JohnNewbury Daw -Memorial Boxford - Ride Brightwalton -

Former Gama Site, Greenham Common, Near Newbury, Berkshire Rg14 7Hq

FORMER GAMA SITE, GREENHAM COMMON, NEAR NEWBURY, BERKSHIRE RG14 7HQ The boundary highlighted above in red is for guidance purposes only. Potential purchasers should satisfy themselves as to the accuracy of the site boundaries. FORMER GAMA SITE, GREENHAM COMMON, NEAR NEWBURY, BERKSHIRE RG14 7HQ. ◆ Former Ground Launched Cruise Missile Alert and Maintenance Area ◆ SPV with freehold for sale, with full vacant possession, no rights of way or easements ◆ Gross site area extending to approximately 73.85 acres (29.89 hectares) ◆ Planning consent for the storage of over 6,000 cars. Suitable for alternative uses subject to planning and scheduled monument consent ◆ Probably the most secure above ground storage available in 6 former nuclear bunkers with additional hardened buildings totalling over 75,000 sq. ft ◆ Opportunity to own a site deemed of national importance Location Newbury is a prosperous Thames Valley town on the River Kennet, 16 miles west of Reading and 8 miles north-west of Basingstoke. The town benefits from its proximity to the M4 Motorway (junction 13, 4miles) to the North and 3 miles from A34 dual carriageway, a major north-south arterial route which can be accessed via the B4640 at Tothill Services. The M3 at Basingstoke is approx. 8 miles Southeast. The property is situated less than 2 miles to the south-east of Newbury town centre and was formerly part of RAF Greenham Common which is now disused. The majority of the former air field buildings now comprise the new Greenham Park Business Park a short distance to the east whilst the remainder of the airfield is now vested in the local authority, West Berkshire District Council. -

Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd

T H A M E S V A L L E Y ARCHAEOLOGICAL S E R V I C E S Land east of Greenham Road, Greenham, Newbury, Berkshire Archaeological Evaluation by Pierre Manisse Site Code: GHG16/113 (SU 4815 6570) Land east of Greenham Road, Greenham, Newbury, Berkshire An Archaeological Evaluation for David Wilson Homes Southern Ltd by Pierre-Damien Manisse Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code GHG 16/113 July 2018 Summary Site name: Land east of Greenham Road, Greenham, Newbury, Berkshire Grid reference: SU 4815 6570 Site activity: Archaeological Evaluation Date and duration of project: 25th June - 2nd July 2018 Project Manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Pierre-Damien Manisse Site code: GHG 16/113 Area of site: 4.23ha Summary of results: Twenty trenches were excavated, with five containing certain or probable features of archaeological interest. These consisted of linear features, interpreted as field boundaries. Two are possibly of Roman or Medieval date, with the others undated. Apart from these features, it is considered that the archaeological potential of the site is low. Location and reference of archive: The archive is presently held at Thames Valley Archaeological Services, Reading and will be deposited with West Berkshire Museum, Newbury, with an accession number assigned in due course. This report may be copied for bona fide research or planning purposes without the explicit permission of the copyright holder. All TVAS unpublished fieldwork reports are available on our website: www.tvas.co.uk/reports/reports.asp. Report edited/checked by: Steve Ford 10.07.18 i Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd, 47–49 De Beauvoir Road, Reading RG1 5NR Tel. -

Local Wildife Sites West Berkshire - 2021

LOCAL WILDIFE SITES WEST BERKSHIRE - 2021 This list includes Local Wildlife Sites. Please contact TVERC for information on: • site location and boundary • area (ha) • designation date • last survey date • site description • notable and protected habitats and species recorded on site Site Code Site Name District Parish SU27Y01 Dean Stubbing Copse West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU27Z01 Baydon Hole West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU27Z02 Thornslait Plantation West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU28V04 Old Warren incl. Warren Wood West Berkshire Council Lambourn SU36D01 Ladys Wood West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36E01 Cake Wood West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36H02 Kiln Copse West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36H03 Elm Copse/High Tree Copse West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36M01 Anville's Copse West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36M02 Great Sadler's Copse West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36M07 Totterdown Copse West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36M09 The Fens/Finch's Copse West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36M15 Craven Road Field West Berkshire Council Inkpen SU36P01 Denford Farm West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36P02 Denford Gate West Berkshire Council Kintbury SU36P03 Hungerford Park Triangle West Berkshire Council Hungerford SU36P04.1 Oaken Copse (east) West Berkshire Council Kintbury SU36P04.2 Oaken Copse (west) West Berkshire Council Kintbury SU36Q01 Summer Hill West Berkshire Council Combe SU36Q03 Sugglestone Down West Berkshire Council Combe SU36Q07 Park Wood West Berkshire Council Combe SU36R01 Inkpen and Walbury Hills West -

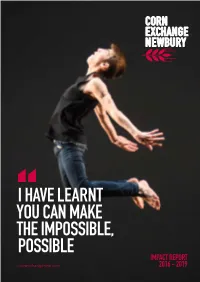

I HAVE LEARNT YOU CAN MAKE the IMPOSSIBLE, POSSIBLE IMPACT REPORT Cornexchangenew.Com 2016 - 2019

I HAVE LEARNT YOU CAN MAKE THE IMPOSSIBLE, POSSIBLE IMPACT REPORT cornexchangenew.com 2016 - 2019 The last three years have been a time of real, tangible growth for the Corn Exchange and the past 12 months have been our most successful ever. The Corn Exchange continues to be the lifeblood of the cultural landscape in West Berkshire and we are proud and passionate to make a difference for our community. Our values of inclusion, excellence and collaboration continually drive us to succeed. We know that our achievements are only possible with your support. I continue to be both overwhelmed and humbled by your huge generosity and the subsequent impact we are able to have. Our donors, funding partners, audiences, participants, collaborators, staff and volunteers are each extraordinary but together enable great success. Our future is bright and positive. We are continuing to establish ourselves as a cultural powerhouse that West Berkshire can remain proud of. We have a local, regional and growing national and international impact and that’s only possible with your ongoing support. You enable us to be ambitious and ensure current and future generations can benefit from the richness of arts and culture we provide. Thanks as ever for your support. Grant Brisland Director We appreciate ongoing support from Sense of Unity Impact Report 2019 3 OVER THE LAST THREE YEARS YOU HAVE HELPED MAKE EVERYTHING WE DO POSSIBLE… 33,085 14 55,673 2,750 PEOPLE HAVE CORPORATE ENGAGEMENTS LANTERNS ATTENDED PARTNERSHIPS WITH OUR LEARNING MADE OUTDOOR SHOWS AND PARTICIPATION -

Planning and Highways Committee 19Th January 2021 Agenda Item No.: 6

Planning and Highways Committee 19th January 2021 Agenda Item No.: 6 Dear Sir or Madam On 6th December 2017, a section 31(6) Highways Act 1980 statement and map was entered onto the West Berkshire Council (WBC) section 31A Highways Act 1980 register, covering land owned by West Berkshire Council and managed by Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Wildlife Trust (BBOWT). A corresponding declaration has now been made and entered onto the section 31A Highways Act 1980 register, as required to complete the process under section 31(6) Highways Act 1980. The process legally demonstrates that there has been no intention of dedicating any additional public rights of way over the affected land shown edged red on the seven attached plans (which are attached as one combine document) during the past three years. Any public rights of way that existed across the land prior to December 2017 are not affected by the process. There is no intention to alter access to any of these sites in relation to the above process, which is a standard process where multiple large areas are open to public access under one ownership. Let me know if you have any queries or need any more information. Kind regards Stuart Higgins Definitive Map Officer Countryside West Berkshire Council Market Street Newbury RG14 5LD This will not affect existing public rights of way that are already recorded on the West Berkshire Council Definitive Map and Statement, or any unrecorded public rights of way that can be proven to exist CA17 (Declaration) Notice Ref. 87 (West Berkshire Council Countryside sites) Notice of landowner deposit under section 31(6) of the Highways Act 1980 West Berkshire District Council An application to deposit a declaration under section 31(6) of the Highways Act 1980 has been made in relation to the land described below and shown edged in red on the accompanying map. -

Map Referred to in the West Berkshire (Electoral Changes) Order 2018 Sheet 1 of 1

SHEET 1, MAP 1 West Berkshire Sheet 1: Map 1: iteration 1_IT Map referred to in the West Berkshire (Electoral Changes) Order 2018 Sheet 1 of 1 Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information applied as part of this review. This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2018. WEST ILSLEY CP FARNBOROUGH CP KEY TO PARISH WARDS EAST COLD ASH CP ILSLEY CP FAWLEY STREATLEY A COLD ASH CP CATMORE CP CP B FLORENCE GARDENS C LITTLE COPSE ALDWORTH D MANOR PARK & MANOR FIELDS CP BRIGHTWALTON COMPTON CP CP GREENHAM CP LAMBOURN E COMMON F SANDLEFORD LAMBOURN CP DOWNLANDS NEWBURY CP CHADDLEWORTH BASILDON CP BEEDON G CLAY HILL CP RIDGEWAY H EAST FIELDS BASILDON I SPEENHAMLAND PEASEMORE CP J WASH COMMON CP K WEST FIELDS EAST GARSTON CP THATCHAM CP L CENTRAL PURLEY ON HAMPSTEAD ASHAMPSTEAD M CROOKHAM NORREYS CP THAMES CP LECKHAMPSTEAD CP N NORTH EAST CP O WEST TILEHURST PANGBOURNE & PURLEY TILEHURST CP CP P CALCOT Q CENTRAL GREAT R NORTH YATTENDON R SHEFFORD CP CP PANGBOURNE TIDMARSH CP SULHAM CP CHIEVELEY CP FRILSHAM CP TILEHURST CP CHIEVELEY TILEHURST & COLD ASH BRADFIELD BIRCH HERMITAGE WINTERBOURNE CP CP CP COPSE WELFORD CP Q P BOXFORD STANFORD TILEHURST DINGLEY CP CP SOUTH & HOLYBROOK ENGLEFIELD HOLYBROOK CP -

Greenham Common Bulletin Learning More About Adders 1St Edition, Summer 2015

Greenham Common Bulletin Learning more about adders 1st edition, summer 2015 (Adrian Wallington) (Adrian Wallington) (Adrian Wallington) Female adder safely held within a Adder fitted with a radio transmitter BBOWT Senior Ecologist Andy plastic tube Coulson-Phillips searches for adders dders have a bad they actually live in the attach a new tag. Using the hibernation locations. reputation being the spaces available to them unique pattern of markings Also it is important for A UK’s only venomous on Greenham Common. upon the snake’s head we populations of adders to be snake, but they are For example; where they make sure that we attach able to integrate otherwise beautiful and very shy hibernate (October to the transmitter to the right detrimental inbreeding may creatures; much happier to Spring), where they give animal. occur. turn tail and hide, unless birth, how they move The information will be you are a vole or a mouse! around the site and how used to generate maps of A Bright Future? They can grow to around they interact with one where the snakes travelled 90cm and are generally another. These questions throughout the summer. Information is key to grey/brown with a all have implications for our These maps can then be safeguarding this intriguing distinctive dark zigzag efforts to conserve the used to direct our animal and maintaining pattern down the back. species and our management of the adders’ Greenham Common as a They are acutely sensitive management of the preferred habitat and make stronghold into the future. to noise and vibration and common in general. -

West Berkshire Reserves and Commons a Business Plan

West Berkshire Reserves and Commons A Business Plan Protecting local wildlife 1 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Partnership Rationale 3. Vision 4 Objectives 4.1 Public Engagement 3.1.1 Access 3.1.2 Events 3.1.3 Environmental Education 3.1.4 Volunteering 4.2 Biodiversity 4.3 Integrated planning 4.3.1 Monitoring and evaluation 5. Context 5.1 West Berkshire Council 5.2 BBOWT 5.3 The Reserves and Commons 5.3.1 Commons and Commoners’ Rights 5.3.2 Privately-owned Sites 5.4 Public Engagement 5.4.1 Access 5.4.2 Events 5.4.3 Environmental Education 5.4.4 Volunteering 5.5 Biodiversity 5.6 Integrated planning 5.6.1 Monitoring and evaluation 5.7 Financial Context 6 Realising the potential 6.1 Public Engagement 6.1.1 Access 6.1.2 Events 6.1.3 Environmental Education 6.1.4 Volunteering 6.2 Biodiversity 2 6.3 Integrated Planning 6.3.1 Monitoring and Evaluation 7 Measuring Success 7.1 Agreeing Measurable Outcomes 7.2 Outcome/output Targets for Year 1 8 Staffing, management, finances and administration 8.1 Management and staffing 8.2 Steering arrangements 8.2.1 Management Committees 8.2.2 Greenham and Crookham Commons Commission 8.3 Project timetable 8.4 Capital Costs 8.5 Revenue Costs 8.6 Additional sources of funding 8.7 Projected budget 8.8 “Frontline” Contact with the Public 8.9 Branding and Recognition 9 Appendices 1 Stakeholders 2 Outline details of sites included in the Plan 3 Maps 3a Map showing West Berkshire Council sites included in the Plan 3b Map showing BBOWT Nature Reserves in West Berkshire 3c Map showing the West Berkshire Living Landscape 3d Map showing the Education Centres in Berkshire 4 Measurable Outcomes 5 Priority Broad habitats in the Berkshire BAP associated with the Reserves and Commons 6 Key skills brought to the Partnership by BBOWT 7 Current Volunteer Groups Regularly Supported by the Partners 8 Current Site Management, Steering and Liaison Groups 9 Common Land proposed for Transfer and the relevant legislation and Schemes of Management 3 West Berkshire Reserves and Commons Business Plan 1. -

The Birds of Berkshire Conservation Fund 2003 - 2020

The Birds of Berkshire Conservation Fund 2003 - 2020 The Birds of Berkshire Conservation Fund was started in 2003 by the Atlas Group with the surplus from sales of the first edition of The Birds of Berkshire. In 2006, it was merged with the Berkshire Ornithological Club’s conservation fund and managed jointly by the Club and the Atlas Group. Following the publication of the second edition of The Birds of Berkshire in 2013 and the success of the Group in raising sponsorship to cover the production costs, we were able to donate all of the proceeds of sales, nearly £25,000, to the Conservation Fund. In total, up to 2020, the fund has received donations of £46,000, two thirds of which arose from sales of the two editions of Berkshire’s atlas and avifauna, with a further £15,000 donated by members. The Fund is dedicated to conservation of wild birds and their habitats and to underpinning research and monitoring in Berkshire. Applications for grants come from individuals or organisations and assessed by the BOC’s Conservation Subcommittee for the conservation benefit they would provide and their feasibility. Applications may be made at any time and usually assessed within a few weeks. The criteria and application form are on the Club’s website http://berksoc.org.uk/conservation/conservation-fund. The Fund has been open for applications since 2003 and it has awarded twenty five grants, involving fifteen different applicants and totalling £18,000. Most applications are unsolicited, though a proportion arise from projects initiated by the BOC. Collaboration is encouraged with other funders or with landowners and others contributing “in kind”, so gearing up the fund’s contribution.