Dubber 1997 Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August/September 2012 75 Finstockserving Finstock, Fawler, Wilcote, Mt.Skippettnews and Finstock Heath

Of the village, by the village, for the village August/September 2012 75 FinstockServing Finstock, Fawler, Wilcote, Mt.SkippettNews and Finstock Heath WI; First Responders; Scarecrow competition ��� 2 Woodpecker; FoFS; Water saving; Recycling ���� 8 Cornbury Park; Home Security; Giveacar ��������� 3 Local Development; Girlguiding; CHOC ���������� 9 District views; Letter; Scrap metal thefts ����������� 4 School; Scouting; Charlbury station �������������������10 Small Ads; Cakes and ale; Saving electricity ������ 5 Forest Fair; Oxfordshire Museum; Carers ����������11 Thermal imaging; BTO; Problem plants ������������� 6 Gardening; Plastics collected �����������������������������12 Post Office & Shop; Local food challenge ��������� 7 his issue of the Finstock News includes your very own Ready Reference, which will give you details of all those people and organisations that you will want to contact in the coming year. Once again we have a Letter to the Editor Taddressing dog fouling. If you own a dog – you own their waste. Four Villages Diamond Jubilee Celebration Thanks to all the villagers who came together at Finstock Playing Fields on Sunday June 3rd to celebrate the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee. The children started the event with a party and painted some wonderful Jubilee themed tiles. We have some budding artists amongst our children! It was lovely to see so many people join together for the community picnic despite the rain falling heavily. Having the time to sit and enjoy the company of good friends and neighbours in our busy lives made the picnic very special. We were wonderfully entertained by Mike Breakell playing his accordion. Ags Connolly started the evening entertainment with a great set and the band Free for All had us all dancing until Ags entertains at Jubilee midnight – starting with the National Anthem and ending with the National Anthem! Due to excellent bar sales, we were able to cover the costs of the event, and we have a small sum left over to contribute towards the children’s commemorative mugs (more details below). -

Oxfordshire. Chipping Nor Ton

DIRI::CTOR Y. J OXFORDSHIRE. CHIPPING NOR TON. 79 w the memory of Col. Henry Dawkins M.P. (d. r864), Wall Letter Box cleared at 11.25 a.m. & 7.40 p.m. and Emma, his wife, by their four children. The rents , week days only of the poor's allotment of so acres, awarded in 1770, are devoted to the purchase of clothes, linen, bedding, Elementary School (mixed), erected & opened 9 Sept. fuel, tools, medical or other aid in sickness, food or 1901 a.t a. cost of £ r,ooo, for 6o children ; average other articles in kind, and other charitable purposes; attendance, so; Mrs. Jackson, mistress; Miss Edith Wright's charity of £3 I2S. is for bread, and Miss Daw- Insall, assistant mistress kins' charity is given in money; both being disbursed by the vicar and churchwardens of Chipping Norton. .A.t Cold Norron was once an Augustinian priory, founded Over Norton House, the property of William G. Dawkina by William Fitzalan in the reign of Henry II. and esq. and now the residence of Capt. Denis St. George dedicated to 1818. Mary the Virgin, John the Daly, is a mansion in the Tudor style, rebuilt in I879, Evangelist and S. Giles. In the reign of Henry VII. and st'anding in a well-wooded park of about go acres. it was escheated to the Crown, and subsequently pur William G. Dawkins esq. is lord of the manor. The chased by William Sirlith, bishop of Lincoln (I496- area is 2,344 acres; rateable value, £2,oo6; the popula 1514), by-whom it was given to Brasenose College, Ox tion in 1901 was 3so. -

Finstock News

Of the village, by the village, for the village April/May 2018 109 FinstockServing Finstock, Fawler, Wilcote, News Mt.Skippett and Finstock Heath Finstock Music day, Spring Plant Sale . 1 Finstock School, FoFS . 7 Village Events . 2 Parish Council, Robert Courts, MP . 8 Village Hall . 3 Shop & PO, County Councillor . 9 District Countil report . 4 Women's article, Oxfordshire Museum . 10 Sm Ads, Women's article . 5 Viv Walk, Charlbury Surgery . 11 Conservation, Toddlers . 6 Gardening . 12 t long last it is spring! As buds turn to blossoms we begin to look at activities outside our homes . There are plenty of interesting options now on offer in the village . On this page you can read about two enjoyable annual events – AFinstock Village Music and the Spring Book and Plant sale . We have updates from all of our representatives in government, our Village Shop and PO and our local school and FoFS group . The Village Hall continues to thrive with regular events and two special musical events on page 3 . Viv gives us two lovely spring walks and Robert brings the best April and May Delights on page 12 . Best of all we have two interesting articles written by women in celebration of The Representation of the People Act 1918, giving some women the right to vote . This series of articles will continue in future issues of the Finstock News . Thank you for your contributions . A commemorative 50p coin to mark the centenary of the passing of the Representation of the People Act will be in circulation later this year . Finstock Village Music May 26th from 1pm Spring Plant Why not come and enjoy Finstock’s smallest event of the year? and Book Fair The phrase Small is Beautiful could easily apply to this festival . -

Finstock News Online At

Of the village, by the village, for the village February/March 2018 108 FinstockServing Finstock, Fawler, Wilcote, News Mt.Skippett and Finstock Heath Right to Vote, Wallhanging, FoFS . 1 Constructing a Female, Cnty Cllr . 7 Village Events, . 2 School, National Theatre Live . 8 Village Hall . 3 Village Hall cont., Shop & PO . 9 Letters, Parish Council, . 4 Finstock Festival . 10 Sm Ads, Robert Courts, MP . 5 Viv Stonesfield Common walk . 11 Conservation, District Cllr . 6 Gardening . 12 igns of spring are beginning to fill our gardens with lovely little snowdrops. Robert talks about MILLENNIUM all the early flowering plants that brighten our gardens and bring food for WALLHANGING the bees on page 12. We have the latest reports from our MP, County At last the Millennium Wallhanging Sand District councillors, as well as our own Parish Council. There are interesting is back in its original home! Although articles from various sources that speak about the use of the Village Hall (now on the actual needlework is still in the pages 3 and 9), the final accounting of the Finstock Festival last year on page 10, Upper Room of the Parish Church, a another great walk from Viv on page 11, a plea for more users of our great amenity photograph, deftly contrived by Neil the village shop and PO on page 9 and the final placement of the Millennium Hanson, shows it in its original unified form. This photograph now hangs in Wallhanging in the hall on page 1. the Village Hall by the door into the large hall. We are most grateful to those who We begin this issue with a new series of articles celebrating the 100th originally supported Pamela McDowell anniversary of the Representation of the People Act 1918, which gave some (some of whom are unknown or women the right to vote. -

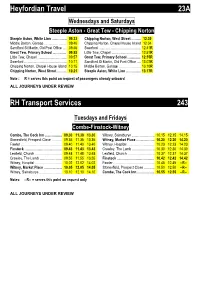

Timetables for Bus Services Under Review

Heyfordian Travel 23A Wednesdays and Saturdays Steeple Aston - Great Tew - Chipping Norton Steeple Aston, White Lion ………….. 09.33 Chipping Norton, West Street ……… 12.30 Middle Barton, Garage ………………... 09.40 Chipping Norton, Chapel House Island 12.34 Sandford St Martin, Old Post Office …. 09.46 Swerford ………………………………… 12.41R Great Tew, Primary School ………… 09.53 Little Tew, Chapel ……………………… 12.51R Little Tew, Chapel ……………………… 09.57 Great Tew, Primary School ………… 12.55R Swerford ………………………………… 10.11 Sandford St Martin, Old Post Office …. 13.02R Chipping Norton, Chapel House Island 10.15 Middle Barton, Garage ………………... 13.10R Chipping Norton, West Street ……... 10.21 Steeple Aston, White Lion ………….. 13.17R Note : R = serves this point on request of passengers already onboard ALL JOURNEYS UNDER REVIEW RH Transport Services 243 Tuesdays and Fridays Combe-Finstock-Witney Combe, The Cock Inn ………........ 09.30 11.30 13.30 Witney, Sainsburys ………………… 10.15 12.15 14.15 Stonesfield, Prospect Close …........ 09.35 11.35 13.35 Witney, Market Place …………….. 10.20 12.20 14.20 Fawler ……………………………….. 09.40 11.40 13.40 Witney, Hospital ………………........ 10.23 12.23 14.23 Finstock ……………………………. 09.43 11.43 13.43 Crawley, The Lamb ………………... 10.30 12.30 14.30 Leafield, Church ………………........ 09.48 11.48 13.48 Leafield, Church ………………........ 10.37 12.37 14.37 Crawley, The Lamb ………………... 09.55 11.55 13.55 Finstock ……………………………. 10.42 12.42 14.42 Witney, Hospital ………………........ 10.02 12.02 14.02 Fawler ……………………………….. 10.45 12.45 --R-- Witney, Market Place …………….. 10.05 12.05 14.05 Stonesfield, Prospect Close …........ 10.50 12.50 --R-- Witney, Sainsburys ………………… 10.10 12.10 14.10 Combe, The Cock Inn ………....... -

DELEGATED ITEMS Agenda Item No

West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Agenda Item No. 5 Between 21 September and 25 October 2016 Application Types Key Suffix Suffix ADV Advertisement Consent LBC Listed Building Consent CC3REG County Council Regulation 3 LBD Listed Building Consent - Demolition CC4REG County Council Regulation 4 OUT Outline Application CM County Matters RES Reserved Matters Application FUL Full Application S73 Removal or Variation of Condition/s HHD Householder Application POB Discharge of Planning Obligation/s CLP Certificate of Lawfulness Proposed CLE Certificate of Lawfulness Existing CLASSM Change of Use – Agriculture to CND Discharge of Conditions Commercial PDET28 Agricultural Prior Approval HAZ Hazardous Substances Application PN56 Change of Use Agriculture to Dwelling PN42 Householder Application under Permitted POROW Creation or Diversion of Right of Way Development legislation. TCA Works to Trees in a Conservation Area PNT Telecoms Prior Approval TPO Works to Trees subject of a Tree NMA Non Material Amendment Preservation Order WDN Withdrawn Decision Description Decision Description Code Code APP Approve RNO Raise no objection REF Refuse ROB Raise Objection P1REQ Prior Approval Required P2NRQ Prior Approval Not Required P3APP Prior Approval Approved P3REF Prior Approval Refused P4APP Prior Approval Approved P4REF Prior Approval Refused West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Application Number. Ward. Decision. 1. 16/01403/RES Freeland and Hanborough APP Erection of four dwellings (amended). 16 Witney Road Long Hanborough Witney Mr Carlo Soave 2. 16/01737/RES Burford APP Affecting a Conservation Area Reserved matters application for 11 dwellings Land North Of Falkland Close Burford Cottsway Housing Association Agenda Item No. 5, Page 1 of 13 3. -

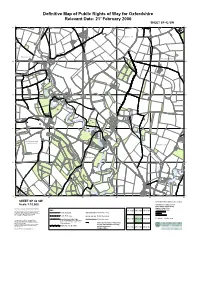

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21St February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 42 SW

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 42 SW 40 41 42 43 44 45 0004 8900 9600 4900 7100 0003 0006 2800 0003 2000 3700 5400 7100 8800 3500 5500 7000 8900 0004 0004 5100 8000 0006 25 365/1 Woodmans Cottage 25 Spring Close 9 202/31 365/3 202/36 1392 365/2 8891 365/17 202/2 400/2 8487 St Mary's Church 5/23 4584 36 0682 8381 Drain 202/30 CHURCH LANE 7876 2/56 20 8900 7574 365/2 2772 Westcot Barton CP 5568 2968 1468 1267 365/3 9966 4666 202/ 0064 8964 0064 5064 5064 202/29 Drain Spring 1162 0961 11 202/31 202/56 1359 0054 0052 365/1 0052 5751 0050 Oathill Farm Oathill Lodge 264/8 0050 264/7 6046 The Folly 0044 0044 6742 264/8 202/32 264/7 3241 7841 0940 7640 1839 2938 Drain 3637 7935 0033 0032 0032 0033 1028 4429 El Sub Sta 3729 7226 202/11 3124 6423 6023 Pond 0022 202/30 365/28 8918 0218 2618 7817 9217 4216 0015 0015 Spring 8214 2014 Willowbrook Cottage 9610 Radford House Enstone CP Radford 0001 House 202/32 Charlotte Cottage 224/1 Spring Steeple Barton CP Reservoir Nelson's Cottage 0077 6400 2000 3900 6200 2400 5000 7800 0005 3800 6400 0001 1300 3900 6100 0005 RADFORD Convent Cottage 8700 2600 6400 2000 3900 0002 1300 24 Convent Cottage 0002 5000 7800 0005 3800 4800 6400 365/4 0001 3900 6100 0005 24 Holly Tree House Brook Close 0005 Brook Close White House Farm Radford Lodge 365/3 365/5 365/4 8889 Radford Farm 0084 6583 8083 0084 202/33 4779 0077 0077 0077 8976 3175 202/45 9471 224/1 Barton Leys Farm Pond 2669 8967 Mill House Kennels 7665 Pond 202/44 2864 6561 6360 Glyme The -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Foxholes Wild Walk

Foxholes Berkshire Buckinghamshire Wild Walk Oxfordshire Explore Foxholes: stroll through Foxholes Nature Reserve rolling countryside, woodland and quiet villages This tranquil woodland, a remnant of the ancient forest of Wychwood, is one of the best bluebell Starting in Shipton-under-Wychwood, this 11 km woods in Oxfordshire. The wet ash-maple woodland circular walk takes in ancient woodland at the Berks, bordering the River Evenlode gives way to beech Bucks & Oxon Wildlife Trust’s (BBOWT) Foxholes further up slope with oak and birch on the gravel nature reserve. plateau within the reserve. 11 km/7 miles (about 2.5 hours) In spring the woodland floor is vibrant with primroses, violets To start the walk from Kingham railway station, allow an and early-purple orchids. More than 50 bird species, including extra hour marsh tit, nuthatch and treecreeper breed in the wood, There are additional paths through Foxholes nature reserve producing a chorus of song through spring and summer. to explore further, including a Wildlife Walk Wild honeysuckle grows in the wood and is the food plant How to get to the start of the white admiral butterflies’ caterpillars. Look for the butterflies flying in the woodland. Numerous other butterfly Postcode: OX7 5FJ Grid ref: SP 282 186 species have been recorded in the wood, including ringlet, By bus: Check www.traveline.info for information about holly blue, and speckled wood. local buses Fungi are abundant here during autumn. Over 200 species have By train: The route starts at Shipton railway station, been recorded including boletes, russulas, milkcaps and false alternatively there is an extension to start from Kingham death cap. -

NRA Thames 255

NRA Thames 255 NRA National Rivers Authority Thames Region TR44 River Thames (Buscot to Eynsham), W indr us h and Evenlode Catchment Review Final Report December 1994 RIVER THAMES (BUSCOT TO EYNSHAM), WINDRUSH AND EVENLODE CATCHMENT REVIEW CONTENTS: Section Piagp 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 2.0 CURRENT STATUS OF THE WATER ENVIRONMENT 2 2.1 Overview 2 2.2 Key Statistics 2 2.3 Geology and Hydrogeology 2 2.4 Hydrology 5 2.5 Water Quality 9 2.6 Biology 11 2.7 Pollution Control 15 2.8 Pollution Prevention 16 2.9 Consented Discharges 16 2.10 Groundwater Quality 19 2.11 Water Resources 19 2.12 Flood Defence 21 2.13 Fisheries 22 2.14 Conservation 24 2.15 Landscape 27 2.16 Land Use Planning 27 2.17 Navigation and Recreation 28 3.0 CATCHMENT ISSUES 31 3.1 Introduction 31 3.2 Water Quality 31 3.3 Biology 31 3.4 Groundwater Quality 31 3.5 Water Resources 32 3.6 Flood Defence 33 3.7 Fisheries 33 3.8 Conservation 34 3.9 Landscape 34 3.10 Land Use Planning 34 3.11 Navigation and Recreation 35 3.12 Key Catchment Issues 36 4.0 RECENT AND CURRENT NRA ACTIVITES WITHIN THE 38 CATCHMENT (1989/95) 4.1 Water Quality 38 4.2 Biology 38 4.3 Pollution Prevention 38 4.4 Groundwater Quality 38 4.5 Water Resources 38 4.6 Flood Defence / Land Drainage 39 4.7 Fisheries 39 4.8 Conservation 40 4.9 Landscape 40 4.10 Land Use Planning 40 4.11 Navigation and Recreation 40 4.12 Multi Functional Activities 40 5.0 PLANNED NRA ACTIVITES WITHIN THE CATCHMENT 41 (1995/96 AND BEYOND) 5.1 Pollution Prevention 41 5.2 Groundwater Quality 41 5.3 Water Resources 41 5.4 Flood Defence 42 5.5 Fisheries 42 5.6 Conservation 42 5.7 Landscape 42 5.8 Land Use Planning 43 5.9 Navigation and Recreation 43 6.1 CONCLUSIONS 44 List of Tables: Table 1 Current GQA Classes in the Catchment 10 Table 2 Description of 5 River Ecosystem Classes 11 Table 3 Water Quality Objectives 12 Table 4 Maximum Volume of Consented Discharges over 5m3/d 17 Table 5 Number of Consented Discharges over 5m3/d 18 Table 6 Details of Licensed Ground/Surface Water Abstractions 21 exceeding lMl/day. -

Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxford Archdeacons’ Marriage Bond Extracts 1 1634 - 1849 Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1634 Allibone, John Overworton Wheeler, Sarah Overworton 1634 Allowaie,Thomas Mapledurham Holmes, Alice Mapledurham 1634 Barber, John Worcester Weston, Anne Cornwell 1634 Bates, Thomas Monken Hadley, Herts Marten, Anne Witney 1634 Bayleyes, William Kidlington Hutt, Grace Kidlington 1634 Bickerstaffe, Richard Little Rollright Rainbowe, Anne Little Rollright 1634 Bland, William Oxford Simpson, Bridget Oxford 1634 Broome, Thomas Bicester Hawkins, Phillis Bicester 1634 Carter, John Oxford Walter, Margaret Oxford 1634 Chettway, Richard Broughton Gibbons, Alice Broughton 1634 Colliar, John Wootton Benn, Elizabeth Woodstock 1634 Coxe, Luke Chalgrove Winchester, Katherine Stadley 1634 Cooper, William Witney Bayly, Anne Wilcote 1634 Cox, John Goring Gaunte, Anne Weston 1634 Cunningham, William Abbingdon, Berks Blake, Joane Oxford 1634 Curtis, John Reading, Berks Bonner, Elizabeth Oxford 1634 Day, Edward Headington Pymm, Agnes Heddington 1634 Dennatt, Thomas Middleton Stoney Holloway, Susan Eynsham 1634 Dudley, Vincent Whately Ward, Anne Forest Hill 1634 Eaton, William Heythrop Rymmel, Mary Heythrop 1634 Eynde, Richard Headington French, Joane Cowley 1634 Farmer, John Coggs Townsend, Joane Coggs 1634 Fox, Henry Westcot Barton Townsend, Ursula Upper Tise, Warc 1634 Freeman, Wm Spellsbury Harris, Mary Long Hanburowe 1634 Goldsmith, John Middle Barton Izzley, Anne Westcot Barton 1634 Goodall, Richard Kencott Taylor, Alice Kencott 1634 Greenville, Francis Inner -

Shakespeare's

SHAKESPEARE’S WAY STRATFORD-UPON-AVON TO OXFORD SHAKESPEARE’S WAY - SELF GUIDED WALKING HOLIDAY SUMMARY The Shakespeare’s Way is a charming 58 mile trail which follows the route that William Shakespeare himself would have taken back and forth between his birthplace in Stratford-upon-Avon to the City of London. Follow in the footsteps of the Bard as he travelled to London to perform his works and make his fortune. Explore the quaint towns of Chipping Norton and Woodstock along the way and marvel at the gardens of Blenheim Palace, a UNESCO World Heritage site, as you meander through the beautiful Oxfordshire Cotswolds. Your journey starts in Shakespeare’s birthplace, Stratford-upon-Avon, a medieval town sitting proudly on the banks of the river Avon. Immerse yourself in Shakespeare’s life and legacy before you leave by visiting the many sites linked to the famous poet and playwright. Leaving Stratford-upon-Avon the path follows the valley of the River Stour before passing through the quintessentially English countryside of the Cotswolds. The beauty and tranquillity of Blenheim Park will make a welcome sight as you approach the historic Tour: Shakespeare’s Way market town of Woodstock. The University City of Oxford is the end point of the walk also known as ‘The Code: WESSPW City of Dreaming Spires’ due to the beautiful architecture of its college buildings. Type: Self-Guided Walking Holiday Our walking holiday on the Shakespeare’s Way features hand-picked overnight accommodation in high Price: see website quality B&B’s, country inns, and guesthouses.