Christy Brown's Depiction of Disability in My Left

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Books Made Into Movies

Made into a Movie Books Made into Movies Aciman, André Call Me by Your Name Alcott, Louisa May Little Women Allison, Dorothy Bastard Out of Carolina Auel, Jane Clan of the Cave Bear Austen, Jane Emma Austen, Jane Pride and Prejudice Austen, Jane Sense and Sensibility 1 Made into a Movie Bauby, Jean-Dominique The Diving Bell and the Butterfly Benchley, Peter Jaws Benioff, David The 25th Hour Berendt, John Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil Brontë, Charlotte Jane Eyre Brontë, Emily Wuthering Heights Brown, Christy My Left Foot Brown, Dan The DaVinci Code 2 Made into a Movie Capote, Truman Breakfast at Tiffany's Capote, Truman In Cold Blood Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de Don Quixote Chabon, Michael Wonder Boys Chevalier, Tracy Girl with a Pearl Earring Christie, Agatha And Then There Were None Clarke, Susanna Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell Cooper, James Fenimore Last of the Mohicans 3 Made into a Movie Corey, James S.A. Leviathan Wakes Crichton, Michael Jurassic Park Cunningham, Michael The Hours Dick, Philip Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Dickens, Charles Great Expectations Dinesen, Isak Out of Africa Donoghue, Emma Room Du Maurier, Daphne Rebecca 4 Made into a Movie Ellis, Bret Easton American Psycho Esquviel, Laura Like Water for Chocolate Fitch, Janet White Oleander Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Flagg, Fannie Cafe Flynn, Gillian Gone Girl Foer, Jonathan Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close Gaiman, Neil Stardust Gaiman, Neil American Gods 5 Made into a Movie García Márquez, Gabriel Love in the Time of Cholera Gilbert, Elizabeth Eat Pray Love Godey, John The Taking of Pelham One Two Three Golden, Arthur Memoirs of a Geisha Goldman, William The Princess Bride Grann, David The Lost City of Z Green, John The Fault in Our Stars Groom, Winston Forrest Gump 6 Made into a Movie Gruen, Sarah Water for Elephants Haley, Alex Roots Hammett, Dashiell Maltese Falcon Harris, Charlaine Dead Until Dark Harris, Thomas The Silence of the Lambs Herbert, Frank Dune Highsmith, Patricia The Talented Mr. -

Title Call # Category Lang./Notes

Title Call # Category Lang./Notes K-19 : the widowmaker 45205 Kaajal 36701 Family/Musical Ka-annanā ʻishrūn mustaḥīl = Like 20 impossibles 41819 Ara Kaante 36702 Crime Hin Kabhi kabhie 33803 Drama/Musical Hin Kabhi khushi kabhie gham-- 36203 Drama/Musical Hin Kabot Thāo Sīsudāčhan = The king maker 43141 Kabul transit 47824 Documentary Kabuliwala 35724 Drama/Musical Hin Kadının adı yok 34302 Turk/VCD Kadosh =The sacred 30209 Heb Kaenmaŭl = Seaside village 37973 Kor Kagemusha = Shadow warrior 40289 Drama Jpn Kagerōza 42414 Fantasy Jpn Kaidan nobori ryu = Blind woman's curse 46186 Thriller Jpn Kaiju big battel 36973 Kairo = Pulse 42539 Horror Jpn Kaitei gunkan = Atragon 42425 Adventure Jpn Kākka... kākka... 37057 Tamil Kakushi ken oni no tsume = The hidden blade 43744 Romance Jpn Kakushi toride no san akunin = Hidden fortress 33161 Adventure Jpn Kal aaj aur kal 39597 Romance/Musical Hin Kal ho naa ho 41312, 42386 Romance Hin Kalyug 36119 Drama Hin Kama Sutra 45480 Kamata koshin-kyoku = Fall guy 39766 Comedy Jpn Kān Klūai 45239 Kantana Animation Thai Kanak Attack 41817 Drama Region 2 Kanal = Canal 36907, 40541 Pol Kandahar : Safar e Ghandehar 35473 Farsi Kangwŏn-do ŭi him = The power of Kangwon province 38158 Kor Kannathil muthamittal = Peck on the cheek 45098 Tamil Kansas City 46053 Kansas City confidential 36761 Kanto mushuku = Kanto warrior 36879 Crime Jpn Kanzo sensei = Dr. Akagi 35201 Comedy Jpn Kao = Face 41449 Drama Jpn Kaos 47213 Ita Kaosu = Chaos 36900 Mystery Jpn Karakkaze yarô = Afraid to die 45336 Crime Jpn Karakter = Character -

Irish Film Institute What Happened After? 15

Irish Film Studyguide Tony Tracy Contents SECTION ONE A brief history of Irish film 3 Recurring Themes 6 SECTION TWO Inside I’m Dancing INTRODUCTION Cast & Synopsis 7 This studyguide has been devised to accompany the Irish film strand of our Transition Year Moving Image Module, the pilot project of the Story and Structure 7 Arts Council Working Group on Film and Young People. In keeping Key Scene Analysis I 7 with TY Guidelines which suggest a curriculum that relates to the Themes 8 world outside school, this strand offers students and teachers an opportunity to engage with and question various representations Key Scene Analysis II 9 of Ireland on screen. The guide commences with a brief history Student Worksheet 11 of the film industry in Ireland, highlighting recurrent themes and stories as well as mentioning key figures. Detailed analyses of two films – Bloody Sunday Inside I'm Dancing and Bloody Sunday – follow, along with student worksheets. Finally, Lenny Abrahamson, director of the highly Cast & Synopsis 12 successful Adam & Paul, gives an illuminating interview in which he Making & Filming History 12/13 outlines the background to the story, his approach as a filmmaker and Characters 13/14 his response to the film’s achievements. We hope you find this guide a useful and stimulating accompaniment to your teaching of Irish film. Key Scene Analysis 14 Alicia McGivern Style 15 Irish FIlm Institute What happened after? 15 References 16 WRITER – TONY TRACY Student Worksheet 17 Tony Tracy was former Senior Education Officer at the Irish Film Institute. During his time at IFI, he wrote the very popular Adam & Paul Introduction to Film Studies as well as notes for teachers on a range Interview with Lenny Abrahamson, director 18 of films including My Left Foot, The Third Man, and French Cinema. -

Teaching Social Studies Through Film

Teaching Social Studies Through Film Written, Produced, and Directed by John Burkowski Jr. Xose Manuel Alvarino Social Studies Teacher Social Studies Teacher Miami-Dade County Miami-Dade County Academy for Advanced Academics at Hialeah Gardens Middle School Florida International University 11690 NW 92 Ave 11200 SW 8 St. Hialeah Gardens, FL 33018 VH130 Telephone: 305-817-0017 Miami, FL 33199 E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 305-348-7043 E-mail: [email protected] For information concerning IMPACT II opportunities, Adapter and Disseminator grants, please contact: The Education Fund 305-892-5099, Ext. 18 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.educationfund.org - 1 - INTRODUCTION Students are entertained and acquire knowledge through images; Internet, television, and films are examples. Though the printed word is essential in learning, educators have been taking notice of the new visual and oratory stimuli and incorporated them into classroom teaching. The purpose of this idea packet is to further introduce teacher colleagues to this methodology and share a compilation of films which may be easily implemented in secondary social studies instruction. Though this project focuses in grades 6-12 social studies we believe that media should be infused into all K-12 subject areas, from language arts, math, and foreign languages, to science, the arts, physical education, and more. In this day and age, students have become accustomed to acquiring knowledge through mediums such as television and movies. Though books and text are essential in learning, teachers should take notice of the new visual stimuli. Films are familiar in the everyday lives of students. -

The Ithacan, 1990-03-29

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1989-90 The thI acan: 1980/81 to 1989/90 3-29-1990 The thI acan, 1990-03-29 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1989-90 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 1990-03-29" (1990). The Ithacan, 1989-90. 14. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1989-90/14 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1980/81 to 1989/90 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1989-90 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ·-· :Ji"~::;;·- vie.,.,.,, ti..;·, ~-~1tfffl-·:ti{· -· -e 1 · .. ·m.... - IC :professot·_:_·gives , ..... ..--~·, . .-: '\.,}t~: . ; ,.: . ,,,;.~~-~- ~ -..-!:~i/f~1;t=t;'J. '... :.I~. __-j~_ -Jl~~;.t~: ..t.: ~ . ~ Midnight Oil unleashes l, .. 1'"1'11'{="\~ : ... :i,·~.JJ.~,t!.!1~.... ~.:~~-t1Tt•.,· or'~',.t.~--... uf;-i ..--~:·,t .. ·.~.- ~·/-. ··glasnost· -7 - ·.:_· .. · .:·:;: .. ·,P~~~pectiVe, 10 p~werful declaration,14 ' ' '. ,._ felllhii~~ THJE T. The Newspaper For The Ithaca College Community Issue l~ March 29, n990 241 pages *lFll'ee Student Government: Candidates square off By Eve DeForest Action ... Let the campaigns begin! The -- ·1 first of several upcoming student ! "When we think of action, we government campaigns kicked off think of movement and change. Tuesday night as the candidates for Our first priority is to take action the 1990 Executive Board addressed on the students' needs. We have to the Student Congress in the Egbert do this in a professional, rational Union. Candidates were allocated and realistic manner." ten minutes to present their This is the way . -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} My Left Foot by Christy Brown MY LEFT FOOT

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} My Left Foot by Christy Brown MY LEFT FOOT. This autobiographical account of a cerebral palsy victim, who for almost twenty years could only communicate with the world around him with his left foot, is not only an amazing account of the determination which can be stronger than any disability- no matter how extreme, but also a ""revelation. of the utmost need of the human soul to escape from every sort of prison"". Dublin born, and one of 22 children of which 17 survived, Christy was declared hopeless at the end of the year and believed to be mentally incompetent as well. But an unconquerable mother gave all the time she could to the child who was totally paralyzed and by the time he was five- Christy was able to prove his awareness when he grabbed a piece of chalk and learned to write with his left foot. The years of his early childhood spent largely with his brothers and in a go-cart was not preparation for the isolation which was to follow as he grew older- the loneliness and withdrawal with a box of paints (he won a contest). Adolescence brought a further despondency, the realization that he didn't want to be remarkable- only ordinary and not ""living in chains""- a pilgrimage to Lourdes proved no cure-and it was finally through Dr. Collis (who contributes the introduction) and with tremendous self-discipline that he abandoned his left foot, and gained a partial mobility, the power to speak, and the chance to develop his writing. -

Welcome to Positive Psychology 1

01-Snyder-4997.qxd 6/13/2006 5:07 PM Page 3 Welcome to Positive Psychology 1 The gross national product does not allow for the health of our children,...their education, or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages; the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither wit nor courage; neither our wisdom nor our teaching; neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country; it measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile. —Robert F. Kennedy, 1968 he final lines in this 1968 address delivered by Robert F. Kennedy at T the University of Kansas point to the contents of this book: the things in life that make it worthwhile. In this regard, however, imagine that some- one offered to help you understand human beings but in doing so would teach you only about their weaknesses and pathologies. As far-fetched as this sounds, a similar “What is wrong with people?” question guided the thinking of most applied psychologists (clinical, counseling, school, etc.) during the 20th century. Given the many forms of human fallibility, this question produced an avalanche of insights into the human “dark side.” As the 21st century unfolds, however, we are beginning to ask another question: “What is right about people?” This question is at the heart of the burgeoning initiative in positive psychology, which is the scientific and applied approach to uncovering people’s strengths and promoting their positive functioning. (See the article “Building Human Strength,”in which positive psychology pioneer Martin Seligman gives his views about the need for this new field.) 3 01-Snyder-4997.qxd 6/13/2006 5:07 PM Page 4 4 LOOKING AT PSYCHOLOGY FROM A POSITIVE PERSPECTIVE Building Human Strength: Psychology’s Forgotten Mission MARTIN E. -

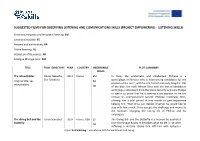

Project Empowering - Listening Skills)

SUGGESTED FILMS FOR OBSERVING LISTENING AND COMUNICATIONS SKILLS (PROJECT EMPOWERING - LISTENING SKILLS) Emotions, empathy and empathic listening: EM Emotional stability: ES Respect and authenticity: RA Active listening: AL Activation of Resources: AR Dialogue Management: DM TITLE FILM DIRECTOR YEAR COUNTRY OBSERVABLE PLOT SUMMARY SKILLS The Intouchables Olivier Nakache, 2011 France EM In Paris, the aristocratic and intellectual Philippe is a Original title: Les Éric Toledano RA quadriplegic millionaire who is interviewing candidates for the intouchables position of his carer, with his red-haired secretary Magalie. Out AR of the blue, the rude African Driss cuts the line of candidates and brings a document from the Social Security and asks Phillipe to sign it to prove that he is seeking a job position so he can receive his unemployment benefit. Philippe challenges Driss, offering him a trial period of one month to gain experience helping him. Then Driss can decide whether he would like to stay with him or not. Driss accepts the challenge and moves to the mansion, changing the boring life of Phillipe and his employees. The diving bell and the Julian Schnabel 2007 France, USA ES The Diving Bell and the Butterfly is a memoir by journalist butterfly AR Jean-Dominique Bauby. It describes what his life is like after suffering a massive stroke that left him with locked-in Project EmPoWEring - Educational Path for Emotional Well-being Original title: Le DM syndrome. It also details what his life was like before the scaphandre et le stroke. papillon On December 8, 1995, Bauby, the editor-in-chief of French Elle magazine, suffered a stroke and lapsed into a coma. -

Drama Movies

Libraries DRAMA MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 42 DVD-5254 12 DVD-1200 70's DVD-0418 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 8 1/2 DVD-3832 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 8 1/2 c.2 DVD-3832 c.2 127 Hours DVD-8008 8 Mile DVD-1639 1776 DVD-0397 9th Company DVD-1383 1900 DVD-4443 About Schmidt DVD-9630 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 Accused DVD-6182 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 1 Ace in the Hole DVD-9473 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 1 Across the Universe DVD-5997 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adam Bede DVD-7149 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adjustment Bureau DVD-9591 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs 1 Admiral DVD-7558 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs 5 Adventures of Don Juan DVD-2916 25th Hour DVD-2291 Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert DVD-4365 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 Advise and Consent DVD-1514 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 Affair to Remember DVD-1201 3 Women DVD-4850 After Hours DVD-3053 35 Shots of Rum c.2 DVD-4729 c.2 Against All Odds DVD-8241 400 Blows DVD-0336 Age of Consent (Michael Powell) DVD-4779 DVD-8362 Age of Innocence DVD-6179 8/30/2019 Age of Innocence c.2 DVD-6179 c.2 All the King's Men DVD-3291 Agony and the Ecstasy DVD-3308 DVD-9634 Aguirre: The Wrath of God DVD-4816 All the Mornings of the World DVD-1274 Aladin (Bollywood) DVD-6178 All the President's Men DVD-8371 Alexander Nevsky DVD-4983 Amadeus DVD-0099 Alfie DVD-9492 Amar Akbar Anthony DVD-5078 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul DVD-4725 Amarcord DVD-4426 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul c.2 DVD-4725 c.2 Amazing Dr. -

Movies and Mental Illness Using Films to Understand Psychopathology 3Rd Revised and Expanded Edition 2010, Xii + 340 Pages ISBN: 978-0-88937-371-6, US $49.00

New Resources for Clinicians Visit www.hogrefe.com for • Free sample chapters • Full tables of contents • Secure online ordering • Examination copies for teachers • Many other titles available Danny Wedding, Mary Ann Boyd, Ryan M. Niemiec NEW EDITION! Movies and Mental Illness Using Films to Understand Psychopathology 3rd revised and expanded edition 2010, xii + 340 pages ISBN: 978-0-88937-371-6, US $49.00 The popular and critically acclaimed teaching tool - movies as an aid to learning about mental illness - has just got even better! Now with even more practical features and expanded contents: full film index, “Authors’ Picks”, sample syllabus, more international films. Films are a powerful medium for teaching students of psychology, social work, medicine, nursing, counseling, and even literature or media studies about mental illness and psychopathology. Movies and Mental Illness, now available in an updated edition, has established a great reputation as an enjoyable and highly memorable supplementary teaching tool for abnormal psychology classes. Written by experienced clinicians and teachers, who are themselves movie aficionados, this book is superb not just for psychology or media studies classes, but also for anyone interested in the portrayal of mental health issues in movies. The core clinical chapters each use a fabricated case history and Mini-Mental State Examination along with synopses and scenes from one or two specific, often well-known “A classic resource and an authoritative guide… Like the very movies it films to explain, teach, and encourage discussion recommends, [this book] is a powerful medium for teaching students, about the most important disorders encountered in engaging patients, and educating the public. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Down All the Days by Christy Brown CHRISTY BROWN, AUTHOR, DIES; CRIPPLED, HE WROTE with TOE

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Down All the Days by Christy Brown CHRISTY BROWN, AUTHOR, DIES; CRIPPLED, HE WROTE WITH TOE. Christy Brown, the crippled Irish author who wrote by typing with the little toe of his left foot, choked to death Sunday while having dinner at home in Parbrook, a village in Somerset, in western England. He was 49 years old. Mr. Brown wrote his first book, ''My Left Foot,'' in 1954. His autobiographical novel, ''Down All the Days,'' was written in 1970 and was translated into 14 languages. It told of the subculture of Kimmage, a working-class Dublin suburb in whi ch Mr. Brown grew up, and earned him $370,000. His most recent work s were ''Shadow on Summer'' and a collection of poems, ''Backgro und Music.'' Mr. Brown was a victim of cerebral palsy. In his early years he could not stand, walk, feed himself or drink. His speech consisted largely of grunts understood by his family and close friends. He could not control any part of his body except his left foot. He would jerk and shake and often slaver. 'The Urge to Write' His mother, who had 22 children, of whom 13 survived, refused to put him in an institution. She taught him to write, and he learned to read and paint - holding a paint brush with the toes of his left foot. Robert Collis, a Dublin physician who specialized in cerebral palsy, encouraged Mr. Brown to write. ''From very early on I had the urge to write,'' Mr. Brown said. ''As far back as I can remember I was always writing bits and pieces - poems, short stories, essays.